How Metal Gear Solid manipulated its players, warning us of an age of Fake News, Cambridge Analytica and data surveillance

Facebook is engulfed in a data privacy scandal with links to behavioural manipulation, but Metal Gear Solid 2 players were exposed to a similar system over 16 years ago

On 16th February, 2018, United States Justice Department senior counsel Robert Mueller indicted 13 Russian nationals over a campaign to influence the 2017 US election. Mueller cited foreign bodies working for the ORGANIZATION, accused of stealing social media profiles from the world’s biggest social network to ‘sow discord in the US political system’. The claims were so fantastical and grandiose as to read like science fiction. Commentators noted the similarities to the script of Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty (MGS2), a 2001 video game by acclaimed director Hideo Kojima. The lines between fantasy and reality were blurred further when actor Paul Eiding, who played Colonel Campbell in MGS2, read Mueller’s transcript, which was later overlaid onto an MGS2 cut-scene causing a flurry of social media interest.

couldn't help but wonder what @4pauleiding's "Colonel Campbell Russia Indictments" audio would feel like as a full-fledged Metal Gear Solid 2 cutscene, so i threw this together: https://t.co/Jj8BjznqOK pic.twitter.com/bg8ZOhyDNPFebruary 22, 2018

Amusing as it was, the meme was shared and forgotten within 24 hours, with few pausing to consider the accuracy of MGS2's predictions of a digital society where personal data held the key to behavioural manipulation. The topic is currently making headlines via a firm called Cambridge Analytica, who harvested over 57m Facebook user profiles to create targeted advertising aimed at influencing voting intentions. The meme became the story, distracting us from closer inspection of Kojima's work. The irony is that MGS2 had warned us how memes were hindering the transmission of worthwhile information by cluttering the world with trivial data.

“In the current, digitized world, trivial information is accumulating every second, preserved in all its triteness. Never fading, always accessible. Rumors about petty issues, misinterpretations, slander. All this junk data preserved in an unfiltered state, growing at an alarming rate. It will only slow down social progress, reduce the rate of evolution.”

Rose and Colonel Campbell, MGS2

Hideo Kojima’s misunderstood MGS2 foretold of a shadowy organisation called The Patriots who aimed to control society through digital manipulation, using social profiling, targeted memes and stealthy pervasion. MGS2's 'villains' aren't an exact analogue of a social media giant like Facebook, or even a data firm like Cambridge Analytica, but more a system of control in which we are active, if unwitting, participants. This is not science fiction, but rather an uncanny prediction of the digital society in which we live today – which affects us all in subtler, more sinister, ways than Mueller’s investigation into voter manipulation – that has already changed our political landscape and capacity for debate.

How has the world been influenced by data profiling and manipulation?

In the last two years, global politics has been transformed by a series of events that defied traditional analysis. While once unthinkable, the emergence of Brexit and Donald Trump dominated the news agenda, as traditional media battled to comprehend a changing landscape. These events have been attributed to a rise in populism, social media and political dissatisfaction; fuelled by simmering racial, economic and nationalist tensions.

What’s only just receiving scrutiny, is the role of big data and personal data profiling in manipulating people’s behaviors – and, in turn, their voting intentions – by targeting their fears and prejudices. In the last few weeks, news outlets like The Guardian, Channel 4 and the New York Times, have intensified their focus on the activities of a firm called Cambridge Analytica – more on them to follow – as part of a wider, systemic, exploitation of Facebook (leading to the #deletefacebook hashtag) and other social media user data.

By exploiting the rules and algorithms that drive Facebook – the world’s biggest social network, with two billion global users – this UK technology company claims to have swung the vote in favour of its backers. More surprisingly, the impact of Cambridge Analytica on current global events carries uncanny similarities to how MGS2 manipulates its lead character, Raiden – and the role of the game’s shadowy ‘enemy’, The Patriots.

How did MGS2 predict our modern digital society?

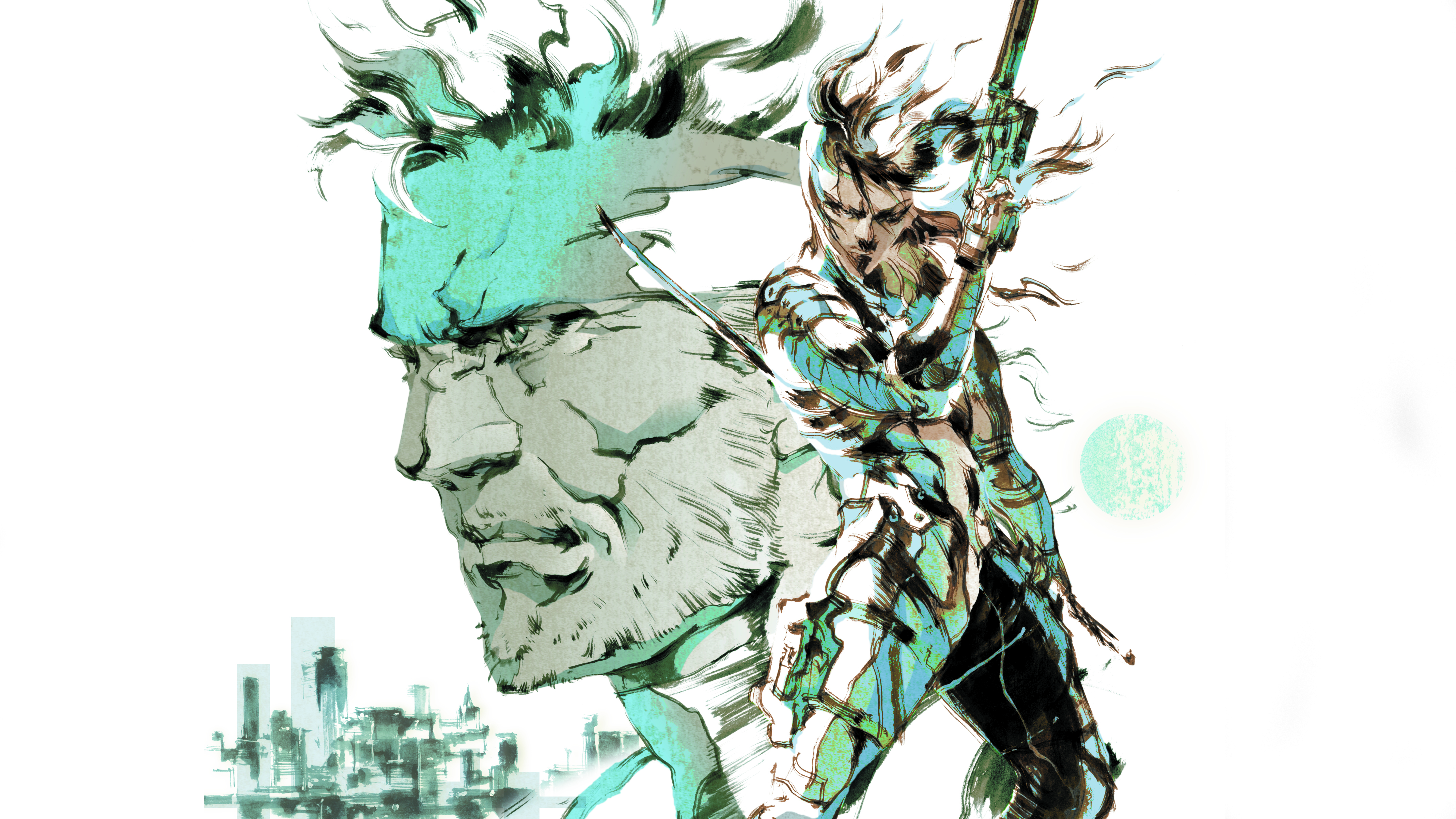

MGS2 is a dense, meta-textual, sequel to one of PlayStation’s most famous games; one that took its fans years to understand. Notionally, it’s a good vs bad tanker heist, where you play – much to many fan’s dismay – an unknown, fop-haired, soldier called Raiden and not the original game’s hero, Solid Snake. This ‘bait and switch’ of the main character is intentional, and used to relay the game’s theme of societal control, the rise of the internet, and the nature of free will. The game’s big twist is that you, the player, are an active – but unknowing – participant in the S3 Plan, aka The Selection for Societal Sanity (camouflaged behind its trial run, the Solid Snake Simulation… look, no one said this was straightforward…), run by the game’s real villains The Patriots. Confusing? Sure, but obfuscation is the point, since systems of control work best when operating by stealth.

MGS2’s closing scenes – where player character Raiden confronts his commanding officer Colonel Campbell, and his girlfriend Rose, who have both deceived him – lift the veil on The Patriots’ plans to manipulate society via information systems, bearing uncanny resemblance to the online world of 2018.

VIDEO: Colonel Campbell outlines the birth of The Patriots and a new digital system of control:

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Rose: Raiden, you seem to think that our plan is one of censorship.

Raiden: Are you telling me it's not!?

Rose: You're being silly! What we propose to do is not to control content, but to create context.

Raiden: Create context?

Colonel: The digital society furthers human flaws and selectively rewards the development of convenient half-truths. Just look at the strange juxtapositions of morality around you.

Rose: Billions spent on new weapons in order to humanely murder other humans.

Colonel: Rights of criminals are given more respect than the privacy of their victims.

Rose: Although there are people suffering in poverty, huge donations are made to protect endangered species. Everyone grows up being told the same thing.

Colonel: "Be nice to other people."

Rose: "But beat out the competition!"

Colonel: "You're special." "Believe in yourself and you will succeed."

Rose: But it's obvious from the start that only a few can succeed...

Colonel: You exercise your right to "freedom" and this is the result. All rhetoric to avoid conflict and protect each other from hurt. The untested truths spun by different interests continue to churn and accumulate in the sandbox of political correctness and value systems.

Rose: Everyone withdraws into their own small gated community, afraid of a larger forum. They stay inside their little ponds, leaking whatever "truth" suits them into the growing cesspool of society at large.

Colonel: The different cardinal truths neither clash nor mesh. No one is invalidated, but nobody is right.

Rose: Not even natural selection can take place here. The world is being engulfed in "truth."

Colonel: And this is the way the world ends. Not with a bang, but a whimper.

The S3 plan is MGS2’s plot device to warn us of behavioural manipulation based on two main pillars: massive-scale profiling of personal data, plus behavioural engineering using this data as a guide. The events of MGS2 – as lived through the eyes of Raiden, the player – demonstrate how our social weak points, like our insecurity about identity, could become glowing targets. 17 years later, we’re learning that these ideas have already been put into action, only not in defence of a political system but rather in assault on it. Somewhere near the centre of it all is a company called Cambridge Analytica, who might be the tip of the iceberg of our modern surveillance society.

How does real world data manipulation link to MGS2's 'villains' The Patriots?

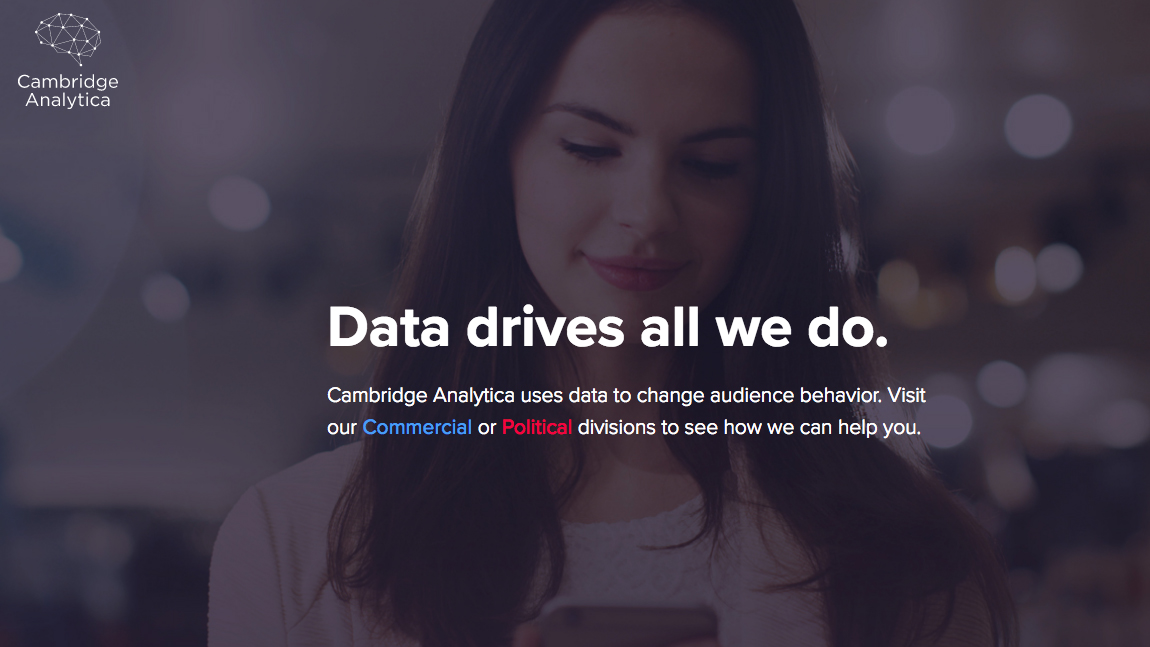

There are a lot of journalistic threads to follow on Cambridge Analytica, from its association with the Brexit and Trump campaigns to more murky links between Cambridge Analytica, various media sites like Breitbart and Infowars, and advanced Search Engine Optimization operations on Google. To take the firm’s business at face value, CambridgeAnalytica.org boasts that it uses data to change audience behaviour, with access to 5,000 data points on over 230 million American voters. The firm’s aim is to ‘build your custom target audience, then use this crucial information to engage, persuade, and motivate them to act’.

According to reports on Cambridge Analytica, the cornerstone of building the ‘target audience’ is social media profiling, with Facebook being a chief source of data. Specifically, your personal data like interests and common keywords can be used to make you a ‘target’, while large groups of people with overlapping data – such as ‘likes’ – can be used to create predictive models of behaviour. The lead scientist at Cambridge University’s Psychometric Centre, Michal Kosinski, estimates that an AI profiler can predict a target’s personality better than their spouse, with knowledge of 150 ‘likes’ on Facebook.

Cambridge Analytica’s artificial intelligence algorithms are able to comb staggering amounts of personal data to accurately identify individuals receptive to their client’s messaging, and deliver that messaging in the way most likely to influence their behaviour. It targets – and alters – this message according to the results from other people who share their same interests and keywords (for example Motorsports fans might see a different headline to Football fans). It connects individuals who share similar profiles and behavioural influences, all the while keeping the messaging and connections hidden from public view – so the ‘targeted’ individual can be fired up on one side of an argument that the public doesn’t even know exists. You can be served personalised messages designed to influence your behavior, playing upon your fears, without anyone else realising.

In short, the system is able to draw a bubble – invisible from the outside world – around its targets, group them into compatible bubbles, then fill those larger bubbles with messaging tailored to what those groups want to hear in order to influence their behaviour. The tribalism of humans can make most of this happen enough organically, making targeted exploitation extremely powerful.

While Metal Gear Solid 2 demonstrates this exact process in action on an individual i.e. your character Raiden, the Metal Gear series at large warns about this inevitable attack by tracing the patterns of information warfare throughout history, from its genesis in Cold War espionage through to its ultimate logical conclusion in the not-too-distant-future. The key stand-in for the runaway power of information warfare are, of course, The Patriots.

Who are the Patriots? How does their system of control mirror modern digital society?

On the surface, The Patriots are the villains of the Metal Gear Solid series. Except they're not really villains. Or people at all. Over the course of the MGS saga, The Patriots evolve from a physical organisation – a collection of powerful individuals united by their philosophy of how the world should be run – into a network of intelligent machines. Led by Snake’s former mentor, Major Zero, they pursue a system of societal stability, which is sceptical of human free will, and evolves into a digital system of control. These AI machines that control the government, the economy, the internet, and the flow of information are the system; the status quo, and represent less a form of wickedness than a series of norms.

The Patriots are The Matrix, Google, Big Brother and all our dystopian fears rolled into one, and have eradicated the world of privacy and free will – even if, ostensibly, we operate under the illusion of choice. Video game villains don't get much more menacing than a formless philosophy that purports to save humanity from itself, with no glowing weak spot.

VIDEO: Big Boss reveals the history of The Patriots in MGS4 (spoilers):

Back in 2018, the world hasn’t created a system like The Patriots by singular will, but rather through technological advancements that were more concerned with how they could change the world, rather than if they should. Facebook, Google, and YouTube have operated with the ‘move fast and break things’ dogma of Silicon Valley, leaving a world remapped by data, engagement and algorithms, ripe for exploitation by self-interested actors, such as those who employed the services of Cambridge Analytica.

"If you’ve finished a video-game, that system has successfully trained and motivated your behaviour to navigate its parameters and reach its desired outcome – all of your own free will."

In MGS2, Kojima uses The Patriots as a metaphor for our growing digital society and – by way of an interactive case-study – the video-game industry and our role within it; illustrating the hidden strings that control our lives: If you’ve ever purchased a video-game you’re a part of an economic system. If you’ve played a video-game, you’ve interacted with a software system. If you’ve finished a video-game, that system has successfully trained and motivated your behaviour to navigate its parameters and reach its desired outcome – all of your own free will. If you’ve played an MGS game, you’ve been confronted with a system that was designed to be completed, and this basic truth is what gives rise to The Patriots as a narrative idea.

In modern life, The Patriots – or rather, The Patriots as shorthand for any system of control – are everywhere. You can see control systems in 20th century industry, modern warfare, and contemporary Big Data, but the more visible they become, the more the central tautology in the 'system of control' is exposed: all systems imply control, and the systems that survive are the ones that avoid detection. Stealth is the optimum tactic for Power as much as it is for solo infiltrators. Cambridge Analytica’s model reached its targets out of the public eye, away from fact-checkers and democratic institutions. Nobody saw those votes coming.

MGS2 forces us to reflect on our role in a system of control

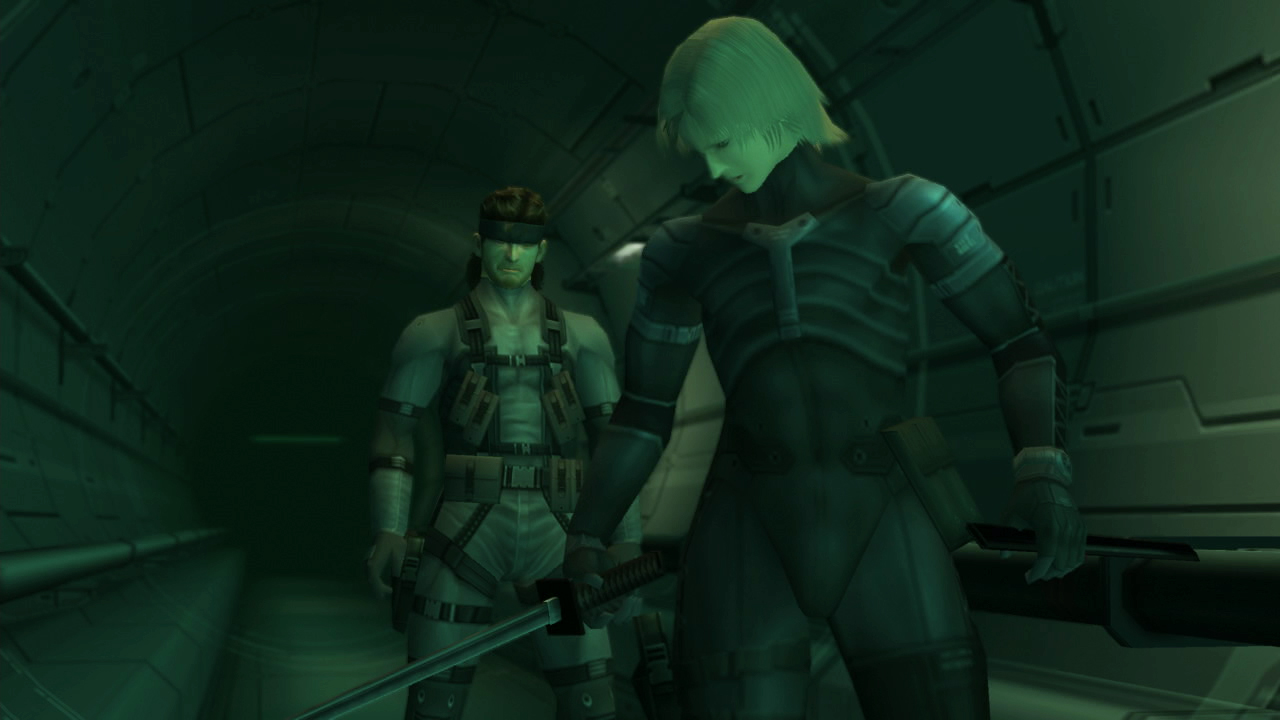

MGS2 brings this concept to life with the revelation than an A.I. network possesses full mastery of our social order, and while this is explained via (lengthy) cut-scenes and Codec chat, it’s also proved mechanically by subjecting the player to its system. The Patriots have engineered a recreation of the Shadow Moses Incident (the plot of MGS on PSone) in order to test their system of control, and in doing so expose the Truth About Videogames: What is an MGS game, if not a carefully balanced system of audio-visual data and feedback sub-loops that are designed to condition the player’s behaviour?

Our mission, as the player in MGS2, has been engineered to be completed, and our avatar has been engineered to have the abilities required to complete the game – to make the impossible, possible. In MGS1 (PSOne, 1998), protagonist Solid Snake is manipulated (and misled) by main villain Liquid Snake to activate giant mech Metal Gear REX. At a broader level, he’s manipulated by The Patriots to spread the FOXDIE virus. In MGS2, the Shadow Moses Incident is re-created to satisfy our superficial expectations of a video game sequel, and the narrative mirrors the original’s structure. To an extent, every MGS game operates akin to the Cambridge Analytica model, probing and subverting the audiences desires and expectations with targeted stimuli to control an emotional and behavioural response.

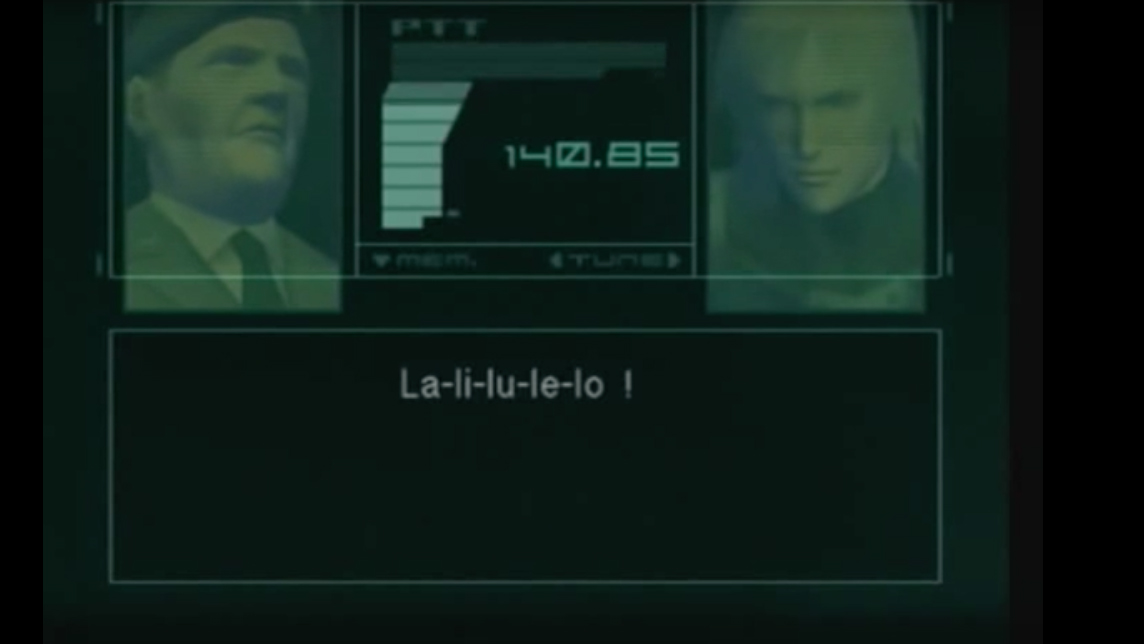

The “code word” of The Patriots is derived from the recitation of the Japanese ‘alphabet’ (Ka Ki Ku Ke Ko, Ra Ri Ru Re Ro” etc.), but “La Li Lu Le Lo” do not exist as characters or syllables (hence “Engrish”). While The Patriots censor their own name into gibberish, in Japanese this extends to hiding in the blind spot of a language system itself. Assuming the form of an idea that cannot be accurately written, expressed or reproduced is the ultimate in memetic stealth. This simple act of censorship is an example of how power thrives in secrecy.

In this sense, the player’s control of Solid Snake is an investigation of what would happen to someone with the abilities of a video-game character in real life i.e. what would happen to a living weapon who could achieve any goal by pressing ‘Continue’ enough times? How would our systems of power exploit such an individual? The Patriots answer, in the original MGS, is to stay well-hidden and manipulate those goals using proven conditioning and messaging (learnt from previous games); a former Commanding Officer-turned-friend, a nuclear threat, a mysterious rival. The player unquestioningly drives Snake through the game because they want to see how it ends; Solid Snake pursues his assigned goals because he’s literally born to obey that urge.

The Patriots maintain their stealth in MGS1; neither Snake or the audience learn about them. The sequel, MGS2: Sons of Liberty, then subverts the expectations of those who enjoyed the original game – who wanted more of the same – as The Patriots go in for the final test: if the system breaks stealth, can it still maintain control? The Patriots communicate directly with you i.e. Raiden, and highlight his circumstances: he can kill Solidus or be killed, and all the free will in the world doesn’t change the boundaries of this system.

How MGS3 went back in time to show the birth of the information age

MGS3: Snake Eater (PS2, 2004), set in the late 1960s, explores the horror of open global conflict in World War II, which caused a shift in military thinking. The U.S., Russia and China transitioned into a Cold War through a new system of battle (and control): information warfare. MGS3 Snake Eater depicts the transition from the Industrial Age to the Information age through its gameplay system. From a defensive perspective, the Cold War system of international conflict requires information control and concealment of power; yet from an offensive perspective, it requires espionage – which gives rise to FOX Unit and the Sneaking Mission. We see this same basic lesson applied in the new form of political warfare in 2016; converting voters is one thing, but converting them in secret was a revolutionary advantage.

This transition leads to the creation of The Patriots. In the old power system, it was powerful public individuals who dominated the Industrial Age, known in MGS as The Philosophers who guided the world from behind closed doors. In the Information Age, it’s now the intelligence agencies of the world that compete in secret over the legacy of power; systems that lie scattered and weakened after a half-decade of open conflict and the theft of their economic leverage.

How are systems of control explored in the wider MGS saga?

Big Boss attempts to forge a path outside of Major Zero’s (and The Patriots) burgeoning systems of control, as a believer in personal liberty. 2005’s MGS: Portable Ops on PSP examines the foreign policy of the time through Zero’s instigation of a coup in sovereign territory. Proxy insurrections in Third World states were the stealth operations of international power projection during the Cold War, and Snake – bound to the Intelligence Community through his ties to FOX – is successfully manipulated by that legal system into clearing Zero from legitimate charges of treason. With Snake as a safeguard against an actual nuclear launch, Zero and Ocelot successfully utilize the coup threat to capitalize on the predictability of the Philosophers and seize their economic assets.

Empowered by his confrontation with Gene and wary of Zero, Big Boss departs in search of a life outside of control systems and makes his greatest error: devising a new system. Big Boss’s Army Without Borders (aka Militaires Sans Frontières or MSF) is a radical idea on the world stage: an entity holding no political allegiance or consideration for the global balance of power, cutting all ties with the societal systems. MSF is a complex beast, its growth requiring staff, infrastructure, intelligence and contracted income, which is dependent on the outside world.

We’ve already seen how subsystems like economics are influenced by the systems of power, and by consciously choosing an indiscriminate system of operation, MSF blinds itself to external influence. This plays out within the interactive systems of 2010’s MGS Peace Walker as a video-game. Peace Walker explores the historical context of private military contractors, and the use of economic systems to sidestep political and legal issues in the pursuit of concealment of power, while the backstory of Che Guevara and the FSLNs struggles against puppet regimes gives us historical examples.

How MGS5 explored 'freedom' within another system of control

There’s also a through-line to 2015’s Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain – narratively we are shown Big Boss going openly rogue and actively opposing the world order, and while the game’s mechanical focus is on freedom, this falls within the constraints of a larger economic system where the narrative freedom to do what you want, is a smokescreen for another system of exploitation. At the same time, Major Zero reaches his epiphany about the true path to control through the power of memes: it’s not about forcing people to do what you want, it’s about ensuring they think they want to do it themselves.

In a micro scale, MGS: Peace Walker's Heroism system positively reinforces the growth of Motherbase for certain actions – stealth, non-lethal play, and recruitment all feed into the growth of MSF. The goal of growing MSF influences the player to act optimally, and by doing so recreate the “historical” legend of Big Boss: the overwhelmingly charismatic and merciful commander. Completion of Motherbase and ZEKE reveals Zero’s true plans, and the true ending. The game’s conclusion is withheld until the player complete Zero’s goals through mastery of Motherbase’s systems. Once again the player experiences the effects of systems of information control.

In MGS2 (set after the events of MGS5), Snake and Otacon later follow this thread by going off the grid, but their goal is to attack the stealth of power by exposing the proliferation of Metal Gears. This significant development of hijacking an existing subsystem – the media – fails by underestimating the depth of system they are up against, and results in the media being wielded against them. Yet Philanthropy’s attempt to turn a subsystem against itself exposes the Patriots and paves the way for the winning play: utilizing the predictability of systems to weaponize them, as we see in the series chronological conclusion, Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriots.

It’s in this approach that we start to see the missing piece in the success of those who utilized Cambridge Analytica for their goals. The predictability of the media – generated from the need for ratings and the desires of mainstream consumers – was used to provoke “us vs them” message that would otherwise need to be generated at cost. In much the same way that The Patriots used The Philosophers predictable economic systems against them, Cambridge Analytica’s clients weaponized the predictability of mainstream media against itself.

MGS tracks how we fought the power… and lost

The Metal Gear games trace a series of failed attempts to fight against society’s systems of control, examining the application of power before demonstrating its endgame. MGS4: Guns of the Patriots presents a scenario in which systems have won. Zero created the most-efficient control system possible by removing the need for human oversight and considered decision-making. This also creates the fatal flaw: the Patriots AI, which administers the system, is itself influenced by feedback and must adjust accordingly.

The Patriots are the mechanism by which Hideo Kojima proposes that the only valid path of resistance to the growing systems of control in our world is to defeat their stealth by educating ourselves about them – where they came from, why they’re successful, what they respond to – and simultaneously uses their narrative context to point to exactly where we can find those answers. Metal Gear Solid is in part a manifesto on the nature of societal control and how to non-violently resist it, and while individual instalments in the series are often lauded as ahead of their time not even Cambridge Analytica could have predicted just how long the warnings of the series would continue to grow more and more relevant.

The recent headlines about data profiling, and Facebook’s role in making us all data points ripe for manipulation by advertisers and interested parties, has echoes of the digital society that MGS2 had predicted 17 years earlier. Metal Gear Solid fans have long argued that the series’ enduring legacy is its social commentary, rather than its focus on stealthy 'hide and seek' gameplay. While recent events might have proved them correct, it’s with no little irony that MGS2’s most damning predictions about our digital society became reality almost completely undetected.

A version of this article originally appeared in the book 'Golden Joystick Presents: Metal Gear Solid' released in 2015.

Check out the top 10 moments in Metal Gear Solid history and why MGS5 is unfinished… and that's entirely the point.

FGS Content Director. Former GamesRadar+ EIC, GTAVoclock host, and PSM3 editor; with - *counts on fingers and toes* - 20 years editorial experience. Loves: spreadsheets, Hideo Kojima and GTA.