I asked a revenge expert why I'm obsessed with retribution in games like Elden Ring and The Last of Us

Getting my own back – the research that could underpin being a digital dickhead

The first time I sought revenge in Elden Ring was against that bastard Tree Sentinel. Anyone who's visited the Lands Between in the last year, assuming you've played past the tutorial, knows the one I'm talking about. That big, bruting, heavily-armored knight on horseback with the magic-reflecting Erdree Greatshield, Golden Halberd, and stinking attitude. The one that waits for you just as you emerge from the Cave of Knowledge, patrolling the grassy thoroughfare between the First Step sight of grace and the Church of Elleh. The one who will kill you again and again because they're big and mean and OP. You could memorize their moveset to prevail. And you could enlist the help of a player-controlled summon. But I much prefer revenge.

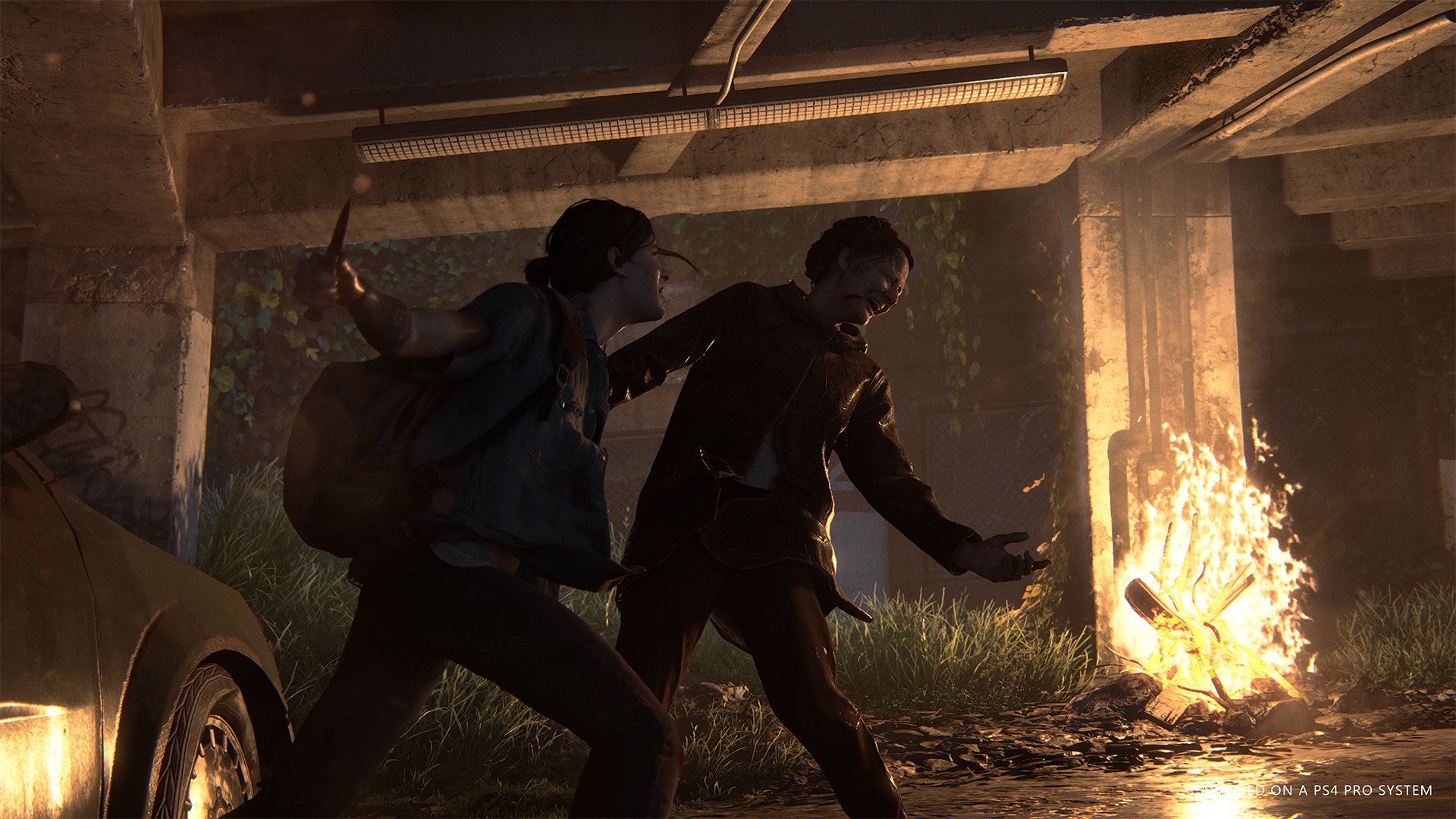

Sweet, cold-blooded, let me level up elsewhere before I come back and valiantly kick your arse revenge. Which is the best tactic in any video game, for my money – be that trouncing Elden Ring Tree Sentinels, slaughtering Skyrim giants, destroying Fallout: New Vegas Deathclaws, or steering an emotionally-charged narrative to conclusion in The Last of Us 2. I love revenge in video games, and I always have. But something I've always wondered is: why?

"Justice violations are a common theme in many video games, where you're the hero. And if there's a hero, there of course needs to be a non-hero. Whether that's an enemy or not is a different question, but that thirst for justice violations is something that comes up in video games a lot," says Fade Eadeh, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Psychology at Seattle University. Eadeh's 2016 academic paper, 'The bittersweet taste of revenge: On the negative and positive consequences of retaliation', explores our appetite as human beings for retribution – an innate desire that Eadeh reckons comfortably extends to virtual worlds. "In everything from Grand Theft Auto to Ratchet and Clank, and The Last of Us, we have so many video game stories that are rooted in revenge, where we as players seek to rectify injustices."

The last word

The perceived justice violation in the above Elden Ring scenario is, clearly, me getting my ass kicked by a bully. The rectification of that injustice takes the form of me upping my stats away from this particular battleground, and then returning a few hours later like Popeye after necking a can of spinach. The boss in question is optional, but giving in to the urge to get my own back isn't – a situation I've found myself in within countless open-world games over the years. In narrative games, however, the idea of revenge tends to be more focused and linear; whereby action X leads to reaction Y which, all going to plan, concludes with resolution Z.

*Beware: The Last of Us 2 spoilers ahead*

To this end, Eadeh says: "There's a lot of research showing that what people do when they're thinking about seeking revenge, they're ruminating or even brooding about the original infraction that made the case for the revenge in the first place. In the case of The Last of Us 2, that could be Abby thinking about her father being killed. It could be Ellie thinking about the way that Joel was killed, taking her all the way to the end of the game, with Dina leaving, and that fight on Catalina Island. That's the negative side of revenge. The positive, again, is that you get to rectify an injustice."

Eadeh says the two-branch story structure of The Last of Us 2 holds a mirror to our actions, whereby we see things through the eyes of, in essence, two wrongdoers – each of whom feels justified in their actions against the other. In doing so, Eadeh says that players are in turn more likely to scrutinize their actions and consider the moralities of the act of revenge itself, which again speaks to the beauty of The Last of Us 2's narrative design.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

"I think that the Naughty Dog team did the best job I've seen, in terms of how we conceptualize and think about the act of revenge, and viewing it from multiple perspectives, and seeing and understanding what motives were at play, why those injustices were occurring, and what drove the motives behind each of the groups seeking revenge," Eadeh says. "Often when games are taking us by the hand, they don't do a great job of conceptualizing what the experience of revenge is like. In a lot of games, you get to the end of the third act, you win, the birds are singing in the trees and you get this wonderful high, but The Last of Us calls into question those motives, and asks if they're appropriate or not."

Question time

For me, the freedom of choice in open-world games makes this process of self-scrutiny even clearer. Take the aforementioned Elden Ring Tree Sentinel, for example. All but one of these foes throughout the Lands Between are optional bosses, meaning you can finish the entire game without paying them any mind. Speaking to this specific Tree Sentinel: once you've reached the save point beyond – ie once you've circumvented the horseback baddie – there's really no need to revisit this particular stretch of the map ever again. Which means my own return to these parts was specifically to exact revenge.

And suddenly I'm having a bit of an introspective crisis. Like, am I the bastard for seeking revenge in the first place? Should I let sleeping dogs lie? Do I even feel better for getting my own back? The answer to those questions is: yes, no, and yes in that order, because I clearly am a bit of a dick in video games. But asking ourselves these questions, Eadeh reckons, is part of what makes us human.

"These moments [in games], hopefully, provide some questions for ourselves," he says. "Like, are we supposed to take revenge? Is this necessarily the best outcome or alternative? Because you see what happens. In The Last of Us 2, the characters are perseverating, they're thinking about [revenge], they're ruminating. I mean, it broke and it clearly fractured Ellie and Dina's relationship at the end of the game. And whether that's necessarily healthy or not, I think that's a good question. I hope that it provides a long-term solution to the act, but I'm obviously doubtful. Either way, I hope it gives people some pause about wanting to engage in those sorts of actions – even though I'm a revenge researcher. And obviously, I find that fascinating."

Paused, thought about your motives, and still want revenge? Seek it in the best FPS games out now

Joe Donnelly is a sports editor from Glasgow and former features editor at GamesRadar+. A mental health advocate, Joe has written about video games and mental health for The Guardian, New Statesman, VICE, PC Gamer and many more, and believes the interactive nature of video games makes them uniquely placed to educate and inform. His book Checkpoint considers the complex intersections of video games and mental health, and was shortlisted for Scotland's National Book of the Year for non-fiction in 2021. As familiar with the streets of Los Santos as he is the west of Scotland, Joe can often be found living his best and worst lives in GTA Online and its PC role-playing scene.