If Disney buys Fox, the first thing it should do is fix Alien. And Star Wars shows us exactly how to do that

Forget the X-Men, bring on the xenomorphs. Alien is in dire need of repair, but it’s still capable of greatness

The Alien franchise, frankly, is in a mess. The current situation is more than sequel decay. We’re now dealing with a once-great film series somehow still flailing to get back on its feet twenty years after it was initially laid to rest. By rights, that kind of a break should have already healed all wounds. However many weak sequels dump upon any particular cinematic legacy, absence, eventually, always makes the heart grow fonder. Or at least, the mind more selective. Nostalgia eventually papers over any residual resentment, setting a clean, refurbished stage for a reboot, hard or otherwise. Hollywood leverages this truth for successful restarts all the time.

It only took eight years to get from Batman and Robin to Batman Begins. The deliriously hard-edged Mad Max: Fury Road picked up business as usual 30 years after Beyond Thunderdome’s descent into Hollywood-friendly lightness of tone, and even Halloween now looks to be getting back on track, after seven sequels and two remake films, simply by ignoring the whole damn lot of them. It looks like one of the best upcoming horror movies of the year, in fact.

Alien though? Alien has had plenty of time and a soft reboot comprising of two prequel films, and things are only getting worse. In fact, in Alien, I’m now forced to draw parallels between where we’re at in 2018 and where we were in 2002 with the middle of the Star Wars prequel trilogy. Each case hinges on a series driven far from its original focus, vitality, and identity by way of bloated backstory movies. In both instances, those movies are defined by poor writing, weak characterisation, and a strange betrayal of their series’ roots by the apparently now misguided original authors.

The parallels don’t end there, and there’s a potential surprise twist happy ending to come as a result. But before we get to it, I want to dig into specifically how wrong the current Alien movies are doing things, and how that can best be fixed. Because really, these films are such a bumble-limbed, out-of-step departure from The Original Point as to be doing a whole new dance. They are The Macarena at a ballet class. They are a kid storming the stage to do the Fortnite Floss during a live performance of Swan Lake.

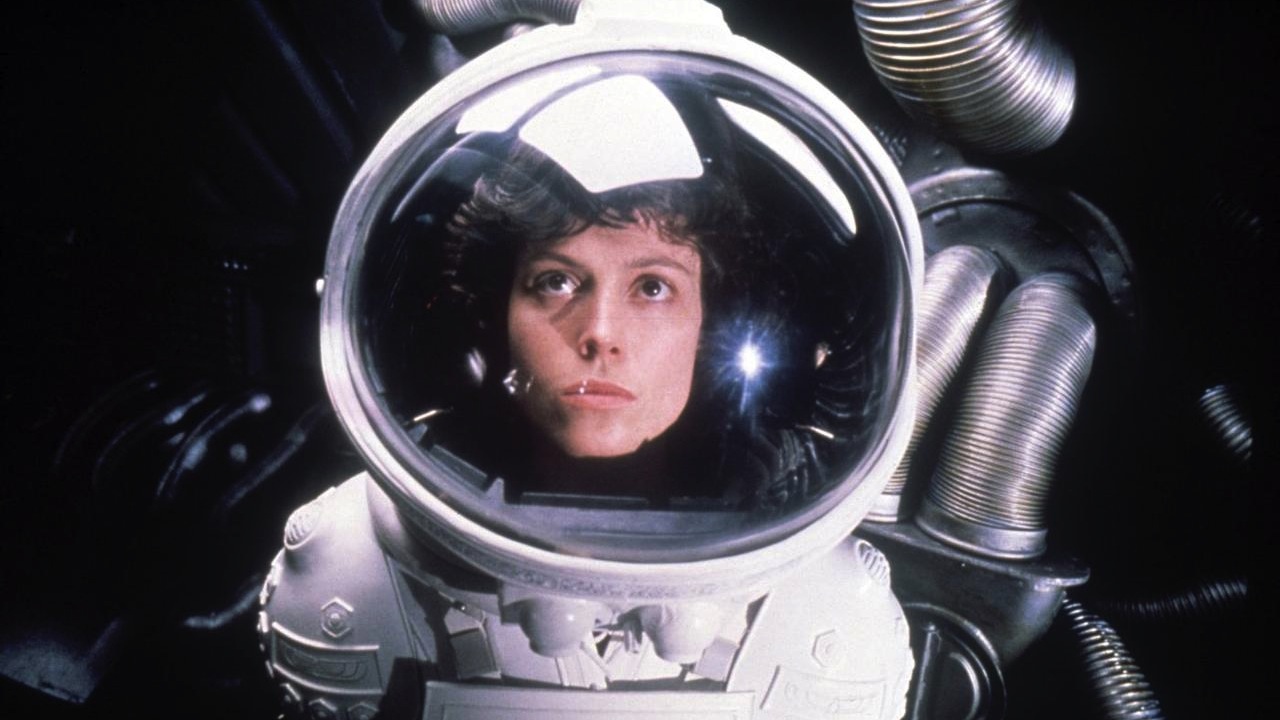

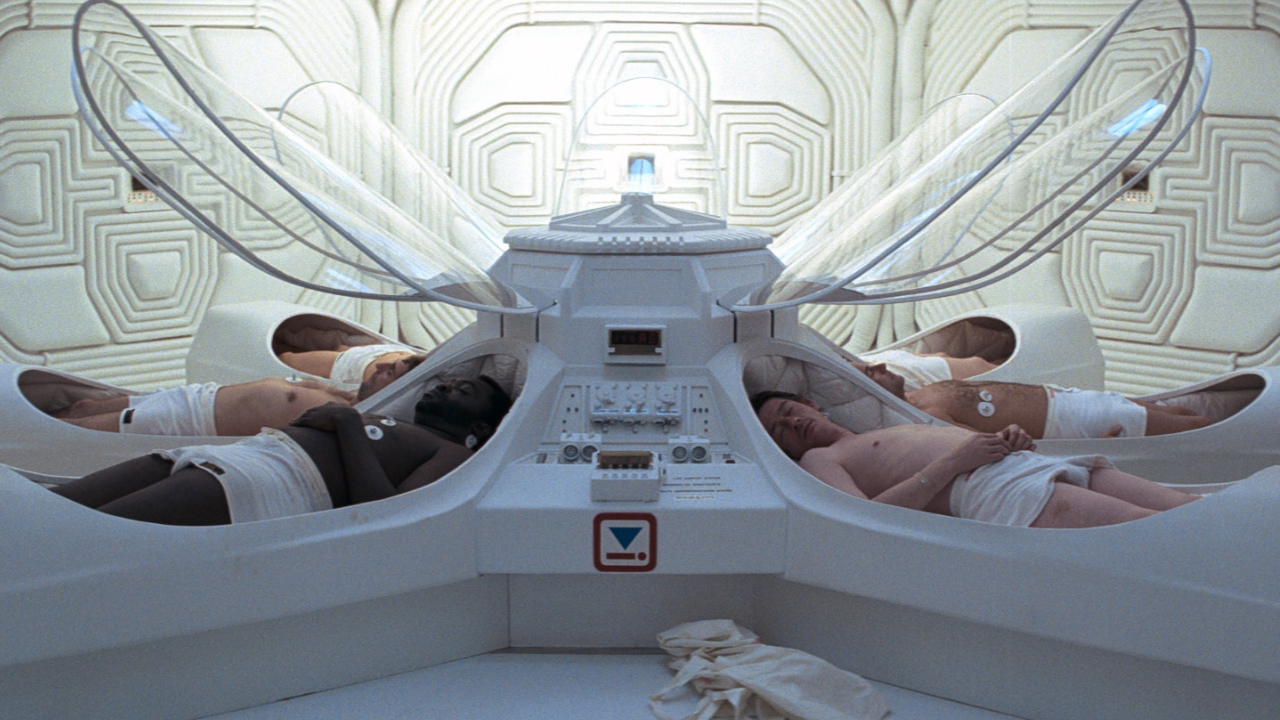

The original Alien trilogy – and yes, I’m counting all three, because I am wise, and will bore you to tears with poetry of David Fincher’s Alien 3 Assembly Cut if you press me on this – is a masterclass in artful horror with a point. Ridley Scott’s first film is a devastatingly low-key ghost story in space, the genre’s traditional supernatural nightmares swapped for an equally unknowable, wraithlike, extraterrestrial demon which - with its truly alien physiology and briefly glimpsed hints of grander purpose - might as well be a jet black mystery torn out of Hell itself.

Around this, the film wraps a grubby, understated character piece full of slow-burn drama, granular human flaws, and escalating, atmospheric dread. Alien is a masterpiece of the ‘believable human nature gets riled up amid claustrophobic horror beyond its understanding’ subgenre. Technically it’s sci-fi, but it’s more Lovecraft than Star Trek. With its clay-thick atmosphere and uneasy psychosexual connotations, Alien isn’t a lasers vs. monsters show. It’s a film about deeply ordinary people having extraordinary visceral and existential horror pushed into their faces and then being forced to sink or swim.

And while the later Alien films are a varied bunch, some consistent threads remain fundamental. Atmosphere and pacing are a given. These are slow, steady films that allow otherworldly threat and menace to infest and define their environments long before a single creature is seen. The mystery is also paramount. The unknown origin, nature, and meaning of the beast, entwined with such specific form and function, infuses it with a uniquely raw, enigmatic power.

Sign up for the Total Film Newsletter

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

And above all, there’s the intimate, personal relationship with the horror. These are films about very different sets of very real people confronting a relentless, primal terror beyond their understanding and being changed by their interaction with it. From the cocky Marines whose overconfident worldview – indeed, whole identity - is shattered in an instant, to the self-exiled murderers and rapists whose attempt to quietly disappear from the universe is disrupted by a final call to responsibility, to Ripley’s profound, central evolution, these films are fundamentally about human horror in incomprehensibly inhuman circumstances.

The prequel films? Prometheus and Alien: Covenant miss every single point. Their characterisation is shallow, cartoonish or non-existent. Their horror is incomprehensible in all the wrong ways, possessing little internal logic and changing the rules on the fly. They swap slow, atmospheric pacing for ‘nothing really happens until the big action movie crescendo’. And perhaps worst of all, they waste every opportunity to make things personal.

Consider Alien: Covenant, if the request to do so is not too rude. Consider Captains Orens. Orens is great. The most dramatically interesting character in the film, he’s the ideal foundation of a powerful Alien movie that alas never gets made. A conflicted but devoutly religious man in a godless, tech-driven universe, he is openly ridiculed but never questions his belief, despite witnessing increasingly nihilistic horror in a world readily leaving him behind. He claims to have seen the devil, years before, and now, in Covenant, finds himself trapped in the middle of a biblical metaphor.

Stranded on an Eden-like garden planet, under the rule of a resentful android in the role of fallen angel, and beset by demonic serpents of partially bio-engineered origin, the entire set-up of Covenant is a horrific, psychodrama subversion of Orens’ beliefs. His mission is that of a combined Noah and Moses, sailing his coupled-up crew, two-by-two, through the empty desert of space to a new promised land. Thematically, Alien: Covenant has an open goal. But it doesn’t even kick the ball.

It kills off Orens before even half exploring his arc, and replaces him with Daniels, a previous non-entity suddenly accelerated to the role of Designated Protagonist because she wears a vest, and the film thinks that will remind people of Ripley. In a film typified by shallow, surface-level nods to previous Alien movies, the whole, sorry mess speaks to a misunderstanding of where the deeper appeal of Alien really comes from. Not to mention the hammer it wilfully takes to mystery. ‘Remember the awe of the Space Jockey?’, Covenant asks. ‘Remember the questions, and possibilities, and the brief glimpse beyond the veil into a vast, ancient universe of secrets? Well forget all of that. A sad robot made the Aliens a few years ago to get back at his dad. This story is actually very small’.

Alien: Covenant ending - 8 questions we need answered

Clearly we need to get off this road. With Scott apparently planning another two prequel films intended to connect right up to the original movie, despite stinking reviews for the two already made, we’re looking at an absolute demolition job if this direction continues. We need to reboot the reboot. In fact we need to just outright cancel it and start again.

You might remember that District 9 director Neill Blomkamp was once looking to make a direct sequel to the original Alien trilogy, ignoring Resurrection and somehow dodging Ripley, Newt, and Hicks’ deaths in Alien 3. I’m not condoning that exact approach, but Blomkamp’s angle does present the seed of a good solution. To fix Alien, you simply kick the very idea of continuity into a kiln, and get back to telling powerful, enigmatic, immediate horror stories again. You drop the overcomplicated bigger picture, and get back to the original heart of things, with new talent that, thanks to a healthy creative distance, is still in tune with it. In short, you - philosophically at least - do what Disney did with Star Wars.

Specifically? You make Alien a true anthology series. You drop the limiting idea of connected narrative, and you set the true potential of the concept free. You make a series of isolated stories, set in different parts of space at different points in time, in which very different people with very different mindsets come into contact with the Alien and have to deal with it in whatever way fits, exploring new themes and spins on the idea each time. You find shocking and surprising ways to reinterpret and explore the essence of the Alien, in order to return the impact, horror, and mystery that used to define the series. Ridley Scott once said, before Prometheus, that the creature was ‘toast’, its mystique ruined by over-exposure. Perhaps that’s why he’s happy to now take a wrecking ball to the mystery. But he’s wrong. The Alien just needs to be thought about in a bigger way.

The wider world of Alien media has done that very well for years. The comics and novels have long explored fresh interpretations of the Alien threat, in new formulations and situations. And you only need to look at the many different, unmade scripts for Alien 3 to see how things could go. A naively idealised, ‘50s-themed, pseudo suburban space habitat being torn apart by xenomorphs, white picket fences shredded by jagged, black tails. A wooden monastery planet devoid of technology but high in religious belief. An airborne xeno DNA virus, capable of infecting and changing any kind of biology without warning, in endlessly unpredictable ways.

If you look at it hard enough, the Alien has limitless potential. The fiction is, like its central monster, a flawless organism, robust, powerful, and distinct, but also ceaselessly adaptable through the malleability of its essence. We know just enough to understand the basic rules and tone, but the greater unknown – and the monster’s very nature as a biological hybrid – means that horrifying reinvention is always possible. Dogmatically carving out a single, linear narrative through which to explain all in a rigid backstory doesn’t merely limit Alien’s storytelling potential, it’s complete anathema to its entire nature.

Just as, in fact, pinning Star Wars down to a single tale, driven by a small pool of overly-connected characters, made its galaxy feel tiny and claustrophobic until the sequel trilogy blew open the horizons again. Alien was never just scary because of the specifics of deadly monster and evil android. It was scary, inspiring, and enthralling because of the bigger ideas and possibilities at play. A return to ideas is what will save Alien.

For fresh ideas, we need fresh talent. Alien needs to be taken away from the single-minded old-guard and handed to new and overlooked writers and directors willing and eager to paint surprising, weird, personal new pictures on its vast canvas. We need the Neill Blomkamps, and the Denis Villeneuves, and Jennifer Kents, and the Jordan Peeles, and the Ari Asters, and the Kathryn Bigelows, and the Rachel Talalays. We need Alien to turn into what John Carpenter originally wanted for Halloween’s sequels. Not a single story, but a loose umbrella series acting as a big-name home to nurture and promote exciting talent. There’s no other horror franchise out there right now with the creative potential Alien has. If that potential continues to be squandered on unwanted and out-of-touch folly, it will be a tragedy.

So Alien needs the Star Wars treatment. The future health of Alien hinges on the same drastic action that undid the prequel trilogy and gave us The Force Awakens, handing Star Wars to a new generation that really understands it. And while that seems a desperate situation, I’m not without hope. Because there is a chance that could happen over the next year or two, depending on how contracts shake down.

Disney continues to circle a buy-out of Alien owner Fox, and the possibility of said buy-out has recently been officially approved. Barring an (unlikely) better offer from CBS, it’s highly plausible that the company that so rapidly turned around Star Wars upon buying Lucasfilm might well own Alien soon.

If there’s one thing Disney recognises, it’s brand power. If there’s a second thing, then it’s brand authenticity. The studio has been relentless in purging the unwanted prequel detritus in order to get back to the heart of Star Wars, even when that has meant seeming to push away from the movies’ traditional comfort zone. If past behaviour is to be taken as evidence, a move to fix Alien might well be within Disney’s plans, should the deal go through. I hope that it is. The potential of the series has always laid in, well, potential. To have new films continue to shrink its scope over the coming years would, really, be worse than no Alien films at all.