The indie gaming revolution: Brave new world, or just a reboot of the same old cycle?

The current indie gaming ‘revolution’ is without doubt a very good thing. In fact in many ways, its advent was as vital as it was inevitable. As great as the passing console generation was--and make no mistake, when you stick your head above the misty mire of day-to-day gaming annoyances and look at just how much the medium developed during those eight years, it really was great--the progressively swelling triple-A focus within the industry crushed a great many under its bulking girth, and eventually threatened to block gaming’s creative pipes good and proper.

Many middle-tier studios fell over the course of the last generation. My much-beloved Free Radical was one of the first to show us just how brutally a single flop could ravage a large-scale, independent studio. And then the domino rally of closures commenced apace, claiming such industry stalwarts as Bizarre Creations, Factor 5, Ensemble and Pandemic. There are dozens more. Check out this list on NeoGAF for a sense of the scale of the problem. Some self-owned studios were bought up by bigger companies and publishers, but plenty more already-owned studios were powered down by their owners. Don’t even get me started on the killing field that was Activision’s studio roster.

Whether studios closed, were bought up, or were bought up and subsequently closed, it became increasingly apparent during generation seven that being an independent studio was no longer a standard, or particularly safe approach to working in the games industry.

But now indie is the new cool thing. We’re in the midst of a revolution, as digital distribution, Kickstarter, et al, are making independent, self-published games a major part of both PC and console gaming. Finally, everything is changing for the better. Finally, after a couple of generations of teething troubles, the games industry has grown up and matured as a holistic, all-encompassing platform. That’s what a lot of people are saying, anyway. But the thing is, I’m not entirely sure that that perception is quite right.

Of course things are better. Boatloads of fresh, new ideas new studios, and new pricing models are hitting mainstream gaming thick and fast. Leftfield, more artistic, and narrative-driven projects feel increasingly less leftfield, and more like a de facto part of the gaming landscape. Smaller scale, shorter-running games are no longer a cheap snack, but a legitimate approach to design. You don’t need to be a billion-seller to make a living and maintain a company. Blockbusters aren’t the standard any more, rather they’re a healthy part of a healthier ecosystem, just like they are in film. I love it. Games are finally, as a medium, at the stage of true maturity I’ve always wanted them to hit.

But as for the cause of all that? I’m not 100% convinced that we’ve hit upon some brave new world of game development here. I don’t think we’ve made any grand new breakthrough discovery. It just seems that games are going back to being made the way they were in the ‘80s. As Thomas Was Alone creator Mike Bithell said to me a while ago, when we discussed indie’s potential impact on the regrowth of British development:

“I think indies, we like to think we’ve invented this. There’s a certain kudos to ‘Nowadays, man, people making games on their own, it’s incredible’. And it’s like ‘Weeell, errrrrr…’ Get yourself a Spectrum at some point and see. There is a history there.”

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

There's nothing new about a small team beavering away at home to make and release their own game. In fact that's just how games were made back then. Yes, the circumstances were different. Games were cheaper, quicker and easier to put together, and distribution via tape and floppy disc didn’t pose anything like the challenges that boxed console publishing does now. But the fact is that the idea of small-scale, independent game development isn’t something that we’ve just invented. If anything, the big publishing model that indie now stands as the alternative to is the new idea. It only exists because it evolved out the bedroom coding foundation of the industry.

Put it this way: Codemasters is a 'big' company. But when I first came into contact with Codemasters, as a gamer, it was a small company specialising in the publishing of small, generally good-quality home computer games, which were sold for £2 – 3. Its biggest franchise was the platform-puzzling Dizzy series. Dizzy was the Spectrum’s equivalent of Mario, and it was created and developed by two people. Those guys were--and still are--the Oliver Twins, Andrew and Phillip.

But the years went on, and things evolved, as they do. Codemasters continued to be successful, and so got bigger, eventually becoming the global publisher it is now. Over the years, Codies published all manner of triple-A games from all manner of developers. The Oliver Twins continued to be successful, and eventually struck out on their own, founding Blitz Games Studios, a large business making triple-A games, family-friendly licensed fare, and educational and training software. Blitz eventually employed around 230 people.

But the years went on, and things evolved, as they often do. Codemasters made the business decision to consolidate its remit and focus its efforts solely on its world-class internal racing game studio, long the source of its most critically successful games such as Race Driver: GRID and the Dirt series. Meanwhile, Blitz Games Studios eventually found its size and financing unsustainable, and sadly folded in 2013.

But a studio closure is never the end of the story. Rather, it’s always the start of several new ones. Seasoned game developers don’t often lose a job and then leave the industry altogether. They get jobs at other studios, or, increasingly these days, set up new, smaller studios of their own and go indie. Did I mention that Mike Bithell used to work at Blitz? And that Thomas Was Alone came from a prototype he created for a Blitz game jam in 2010? Bithell left Blitz before its closure, but you get my point here. As Mike continued during our talk:

“I think we’re going to see some smaller studios, but I think that those smaller studios will most likely grow. It’s a cyclical thing. Obviously Blitz closed recently, Blitz was what, 200 people? It was really, really successful for many years, but that started as two guys in a bedroom. That’s my point. Basically there’s a cyclical element to this, and I suspect some of the people we see now as indies, as bedroom coders, will start to grow and we’ll see the pattern repeat itself”

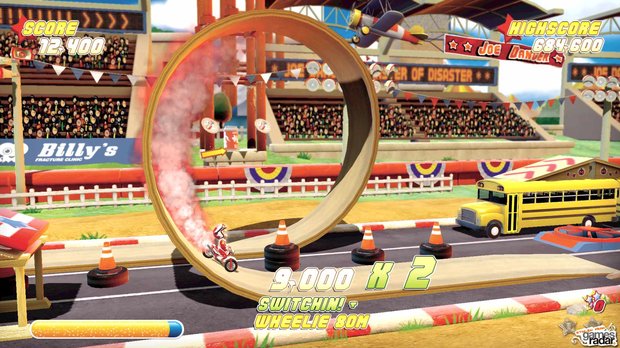

There’s an ebb and flow to these things. Developers start companies. Those companies get big and successful and become part of ‘the establishment’. Some of those companies get too big to maintain themselves. Some of them get bought by other companies, some of them close. Some of their developers get tired of being part of ‘the establishment’ and leave to go it alone. Some of their developers are forced to go it alone when their companies close. See also Hello Games. Hello was founded by four Criterion and Sumo Digital staff who fancied a fresh challenge, and so left to create Joe Danger. Hello is now working on No Man's Sky, a much bigger and more ambitious project, which will doubtless require expansion over the course of its development. And so the cycle continues.

It’s easy to see all of this as part of one long, linear narrative, particularly when this first loop has taken so long that we’re still now only just reaching its end. But I can’t help suspecting that we’re really in a Battlestar Galactica-style 'All this has happened before. All this will happen again' situation. After all, let’s not forget that Activision--the spirit animal of big-budget, mega-corp. game publishers--was initially set up as a rebellious, developer-led splinter group from Atari, which had itself become the modern-day Activision of its time.

The big question for me is not whether today’s bedroom indies will become tomorrow’s big studios, but how long that will take and how much digital distribution will shape their development. Download sales are not going to go away in the same way that early storage media did, so while studios will grow, it will be easier, for a while at least, for them to handle things on their own. And via self-publishing, on console now as well as PC, the resolutely small-scale dev, the one with no desire whatsoever to grow into a mega-studio, will be able to maintain that status in a way that wasn’t possible before.

Crowdfunding, and whatever that develops into over the next few years, will very probably help for a while as well, but trying to predict how Kickstarter et al are eventually going to settle in as part of the games industry--if they’re going to at all--is to open multiple cans of worms stacked within each other like Russian dolls.

Will digital allow studios to grow while remaining utterly independent? Or will spiralling ambition and entirely legitimate desires to develop the scope of projects again lead to furtive glances towards the big guys’s development budgets? Or will, in fact, the new indie devs eventually become the big guys with the budgets. With so many variables thrown into the mix this time around, the finer details are impossible to plot out. But I reckon I can be pretty sure of the overall direction of the journey. Shall we check back in in another 30 years and take another look?