Inside the revival of social stealth games

How social stealth found its audience in the world of indie multiplayer

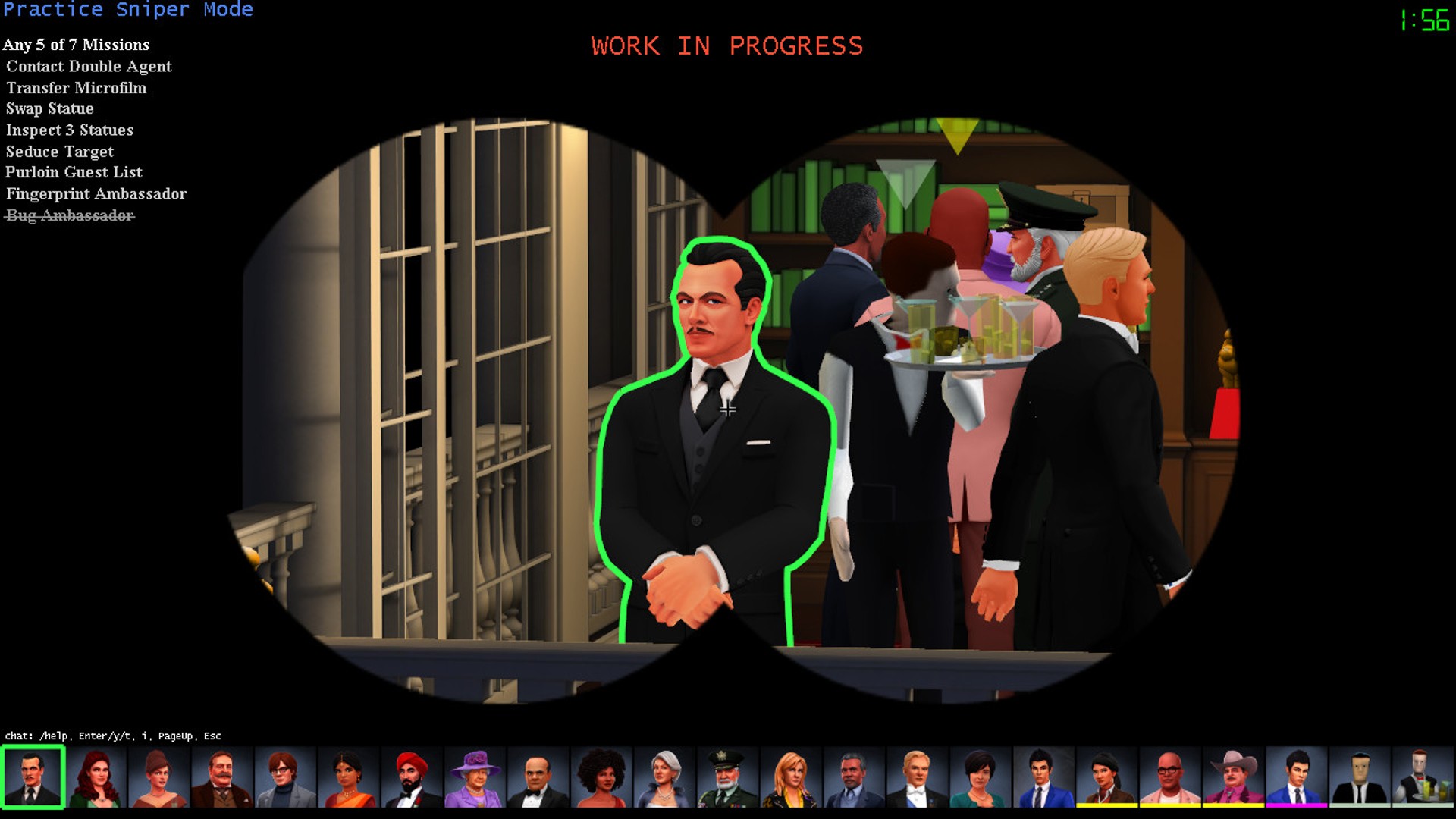

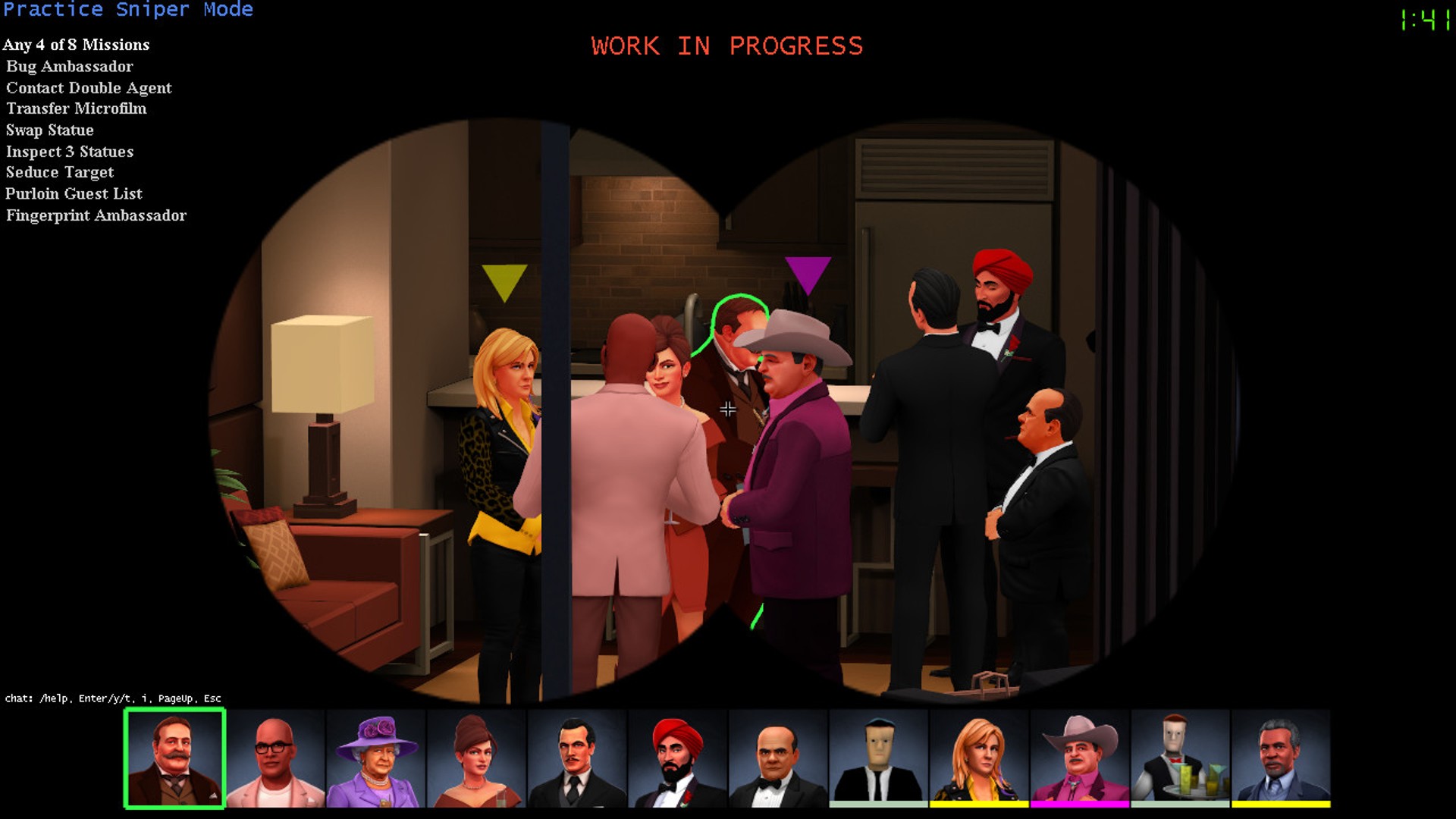

Will Wright is certain: "That’s not gonna work." Maxis is mid-development on Spore, and an engineer named Chris Hecker is describing an ambitious side project. An asymmetrical multiplayer game called SniperParty, its premise is as binary as its title: one player attends a party as a spy, blending into the throng of mannered guests while surreptitiously swapping statues and planting bugs on ambassadors.

Meanwhile, a second player with a sniper rifle occupies a roof across the street, with a single task: they must pick out the spy in the crowd and take the shot. But they need to be sure of their target because they have just a single bullet. For the sniper, the game is about reading social cues, spotting a strange gesture or conversation cut short and mentally building the case against a suspect.

Crowd cover

This article first featured in Edge Magazine – check out subscription options at Magazines Direct

It’s a design that tends to quickly woo those who hear about it: easy to grasp, yet dense with possibilities. SimCity creator and industry mentor Wright, however, isn’t on board. "It’s gonna be too easy to tell who the player is," he concludes. As it turns out, Spore will be a grand lesson for Wright in what works and what doesn’t. But the assessment his game receives gives Hecker pause. "When game design genius Will Wright tells you that your game’s not gonna work, you’re like, 'Ah, shit,'" he remembers.

Ironically, it was Wright and EA who had enabled Hecker’s experiment in the first place. Hecker negotiated the use of assets from The Sims, Wright’s breakout paean to domesticity, in the 2005 Indie Game Jam. Then in its fourth year – and still a few more away from the indie boom that would be triggered by regular participant Jonathan Blow – the event challenged participating designer-programmers to explore human interaction. "Some of us organisers thought, well, there aren’t a lot of games about normal people," Hecker says. "People in the world – not space marines."

If that’s true today, it was considerably more so at the time. Entrants had few examples to draw from. But Hecker recalled a previous Indie Jam entry, Thatcher Ulrich’s Dueling Machine, in which a Doom avatar with a single bullet hunted a target player hidden by thousands of sprite pedestrians. "What’s the intimate version of that?" he wondered. Among the selection of NPCs that The Sims could muster, one differently modelled character would be immediately distinguishable. But if that character was physically anonymous, dressed like any other guest, a searcher would have to rely on subtler tells.

"I got a room full of characters walking around," Hecker says. "They would pause, play a talk animation to each other and then walk away. Really simple – no missions, no nothing. And I put one of them under my control. He recorded a video and sent it to Wright as a kind of digital Where’s Wally? test. It was a success. Wright couldn’t pick out the player. As soon as I came up with the spy and the sniper, the game basically designed itself," Hecker says. That was true up to a point: a decade and a half later, he is still designing the game, developing an evolving build in public. Now called SpyParty, it has inspired a new multiplayer genre, a crowd into which it easily blends. In these games, stealth happens in the daylight, as targets brazenly attempt to pull the wool over their predators’ watching eyes. It’s taken over a decade to rise to prominence, a period during which the mainstream game industry embraced the trend and then abandoned it.

Out of the shadows

"No one at the triple-A level has worked out how to make this genre work as something you can put 100 people on."

Chris Hecker, game developer

Back in 2005, just as Hecker was happening upon the project of his career, triple-A developers around the world were searching for next-gen concepts that would sell their games on PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360. Ubisoft found its million-dollar idea in crowds – masses of on-screen NPCs fuelled by the bonus RAM of new hardware.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

“We’re going to show off something that we call social stealth,” then-Ubisoft executive producer Jade Raymond said when introducing Assassin’s Creed at E3 2006, coining a term in the process. “This is an idea that you’re not hidden when you’re in shadows, you’re hidden when you’re doing things that are socially acceptable.” There was a truth there, certainly more than the stealth genre’s traditional focus on light and shadow. With that mechanic seeming dated by its association with the ’90s, blending in with crowds seemed like the future – and for a few years, it was.

Assassin’s Creed was a hit, and by the time of its second sequel, Brotherhood, Ubisoft introduced a multiplayer variant to the mix. Hecker was beginning to sweat. “It was in closed beta after I had announced SpyParty, and I was a little bit nervous,” he says. “I was like, ‘Oh, man, everybody’s really catching on to this. I’m just this tiny little indie game’.” He needn’t have worried too much, as it turned out. Though it certainly belonged to the same crowd, Assassin’s Creed’s multiplayer wasn’t quite shoulder-to-shoulder with SpyParty. Its design was symmetrical, each assassin tailing one player while evading another, an ouroboros of disguises and hidden blades. And while elegant, it was fundamentally flawed.

“The designers couldn’t make the [social] tells really subtle, because you as a hunter are constantly having to watch your back,” Hecker notes. “You couldn’t spend that much time looking around.” The problem went unaddressed in subsequent iterations, and when Ubisoft dropped competitive multiplayer from the series, few complained.

Before long, social stealth started to die out in Ubisoft’s single-player games too. The Assassin’s Creed missions that foregrounded blending into crowds, asking you to tail targets through cities and eavesdrop on their conversations, were a persistent source of complaints from players who found such sequences contrived and fiddly. Today, the series has almost entirely stripped out social stealth mechanics in favour of hiding behind cover or stepping out into open combat. A planned crowd-blending reboot of Splinter Cell was similarly scrapped, and more recently Watch Dogs: Legion launched without the PvP invasion mode of previous instalments.

“No one at the triple-A level has worked out how to make this genre work as something you can put 100 people on,” Hecker says. Square Enix appeared to agree when it dropped Hitman developer IO Interactive from its studio roster in 2017, swallowing a loss of $43 million in the process. Hitman had been critically acclaimed for its use of player disguise in busy environments, but Square Enix said it preferred to focus on “key franchises”, which could “maximise player satisfaction as well as market potential”. In other words, for a major publisher, social stealth simply wasn’t bankable enough.

In plain sight

Having sold the public on its potential but failed to work out the kinks, the mainstream industry left social stealth to the indies, right at a time when self-publishing had become feasible and affordable. A hobbyist named Adam Spragg read about SpyParty and was inspired, before actually trying it himself, to make his own game about players mingling with NPCs. The result was Hidden In Plain Sight, which he paid $99 to publish on the Xbox Live Indie Games marketplace. It was a shrewd investment: the game’s sustained success since has funded a slew of ports, most recently to Switch, where it arrived this March. “After playing SpyParty, I was relieved to find the games are nothing alike,” Spragg says. “There is plenty of room for both games and more to exist in this genre.”

Hidden In Plain Sight floods the screen with identical ninjas, almost all of whom stride aimlessly about a large hall in accordance with their basic AI. Up to four of those ninjas are players – though which is initially a mystery even to the players themselves, who must first identify their own avatars amid the herd. That done, their goal is to find and kill their fellows by analysing movement patterns.

It’s easy for players to mimic the predictable perambulation of the NPCs, so Spragg added potential win states that would tempt them to deviate from accepted behaviour: touching statues and picking up coins. “They want to do two opposite things at the same time,” he says. “I think it is exactly this tension, and its resolution, that makes the game fun.”

In one mode, Death Race, players become spy and sniper at the same time, creeping towards a finish line with one hand while aiming a crosshair with the other. Separating from the NPC flock too early is suspicious and risks drawing bullets – but wait too long, and players will miss their opportunity.

“People quickly discover the ‘put the gun sight on my own character’ bluff,” Spragg says. “The games tend to last longer and longer as players gain experience because people learn to reserve their shot until it really matters. This leads to a large crowd just inches from the finish line, waiting to not be the first one to run for it.” It’s messier than SpyParty, less nuanced – but, crucially, it’s funny. The genius of Hidden In Plain Sight was to turn the social stealth game social.

"SpyParty’s depth lends itself to tournaments and leagues – the kind of cultures that attract hardcore players and put off those looking for casual, social matchups."

“Once I had a working version of the game, I lugged my Xbox 360 to a friend’s holiday party to see if I could get them to help me test it once the party was over,” Spragg recalls. “Watching them play, I had this wonderful moment of realisation that they weren’t just humouring me. I left ‘early’ at 1am, but they wouldn’t let me take my Xbox home.” The game was tense enough to engender competition, but silly enough to keep things light.

Spragg committed to local multiplayer only, making Hidden In Plain Sight a party game by design. “You are hiding from a person who’s literally sitting right next to you,” he says. “It took me a while to realise it, but what I finally discovered is that the fun of the game actually takes place in the physical space of the room, in the air between the players. The stuff on the screen just facilitates that interaction.”

Despite the tendencies of the games it has inspired, SpyParty itself isn’t a party game. It accommodates just two players, and has a tendency to become deeply competitive.

“I was really into Counter-Strike, and I knew I wanted a high- player-skill game,” Hecker says. Spies are given a range of actions to get to grips with, and snipers an equal number to keep track of. Hecker has even identified ‘types’ of top snipers: behaviourists, the ‘voodoo’ killers who rely on a sense of the uncanny emanating from their target; campers, who keep their scope trained on the ambassador and the statues, the parts of the map that offer hard tells; and etiquette snipers, who specialise in identifying breaks in the flow of natural conversation. “It’s really small stuff that changes all the time as I update the code, so these people have to constantly spelunk for new etiquette tells.” SpyParty’s depth lends itself to tournaments and leagues – the kind of cultures that attract hardcore players and put off those looking for casual, social matchups.

There is, however, a social ‘fuzziness’ naturally inherent to SpyParty that Hecker has learned to lean into more over the years. “I thought I was making Go,” he says, “a crystalline, full-knowledge strategy game. And it turned out the game I was actually making was poker. It’s all about probabilities and suspicion, bluffing and figuring out how much you know. A big part of game design is listening to the game, and you’ve got to follow.”

SpyParty may not lend itself to gatherings, then, but it does reflect social interaction in a real way. Conversation, after all, is a game in which you read another person to try to discern their intent – attempting to divine sense from words and gestures that could mean any number of things depending on their context. SpyParty is much the same. “You make a model of what’s happening,” Hecker says, “and then you do your post-game analysis.” It’s the same ruthless self-admonishment that takes place in our brain the moment we step into the shower after a party.

The mask slips

At the fuzziest end of the social stealth spectrum is Among Us, a spaceship horror game that doesn’t so much map social interaction to mechanics as step out of the way and let conversation take over. Mic chat opens up in emergency crew meetings, during which players accuse each other of murder, or cover up their own by bluffing, deflecting and framing others.

Belonging to a long history of ‘hidden killer’ parlour games stretching back to the ’80s, Among Us was released to little fanfare in 2018. The game rose to pop-cultural prominence during the COVID-19 pandemic precisely because of its social aspect. Its success ensures a high-profile future for social deduction as raucous party entertainment.

What games like Among Us lack, though, is the idiot robot: a limited AI that players must mimic in order to blend in. It’s the NPCs, social stealth developers have discovered, that give players a dance to learn – and consequently, a sense of mastery when they get it right. In Unspottable, a multiplayer crowd blending game from French-British indie studio GrosChevaux, the NPCs are explicitly characterised as automata – metal humans that move in jerky, erratic patterns.

“Their behaviour is a bit different from map to map and always slightly randomised,” says GrosChevaux co-founder Gwé Limpalaer. “Pushing the players to do silly things like running against walls or spinning in circles was an opportunity we could not miss.” It’s the kind of NPC activity that would break the illusion in a big-budget single-player game such as Assassin’s Creed. “[Their] AI needs to be very smart, varied,act and react as crowds and be able to surprise players in some ways,” Limpalaer says. But in an online game, flawed or clumsy AI is ripe for comedy – making social stealth viable for indies who can’t spend years perfecting patrol behaviour.

What’s more, PvP circumvents the frustration players feel when they’ve been unfairly spotted, since all the spotting is carried out by human beings. “Disguise and cover in a singleplayer game is really just smoke and mirrors,” Spragg says. “The game code obviously knows exactly where you are at any moment. In a multiplayer stealth game, the stealth is real.”

"Whether it’s driven by AI or repurposed player data, the best social stealth is never going to be solely simulation. The genre comes to life when it invites the gaze of a second human being, or a third, or even a fourth."

Stealth games, social or otherwise, have always thrived on the David-and-Goliath sense of a wily underdog running rings around a better-armed opponent. And in multiplayer, that sense is amplified – even if, as in SpyParty, the difference is just one bullet. Outsmarting a real person taps into something fundamental and thrilling. “It’s got this frisson, this deeper, lizard brain, visceral component to it,” Hecker says.

“You are competitive with someone you are otherwise friendly with,” Spragg adds. “Humans are social creatures and have evolved with cooperation and competitiveness as critical traits. So there is something deeply primal at play that just doesn’t exist when playing against a computer.” Hecker, who has remained a constant in the social stealth genre while its fortunes have waxed and waned, suspects that it may be cyclical. “There’s always [social deduction card game] Werewolf,” he says. “It gets really big for a while, and then fades away as everyone moves on to the next thing, and then it comes back. That’s part of what happened with Among Us – it was just time for another Werewolf.”

A big-budget social stealth resurgence may be on the cards. Ubisoft has promised an invasion mode update to Watch Dogs: Legion, albeit reluctantly – it appears to be at the bottom of the dev team’s priority pile. And IO Interactive has flourished as an independent. Hitman’s recent iterations even have a crowd- blending mechanic identical to that of Assassin’s Creed Unity, in tacit recognition of Ubisoft’s achievements in social stealth.

The publisher may be eyeing Hitman 3’s celebrated release and wondering whether it shouldn’t have another go after all. Hecker might even have a solution to social stealth’s singleplayer AI problem. If you log into SpyParty and click the new Daily Challenge button, you can play against a previously recorded spy. “You’re playing as the sniper from the past,” Hecker says, “anywhere from a week ago to three years ago. The one flaw is that there’s no feedback between sniper and spy – that [recorded] spy can’t know where your laser sight is and change their behaviour. But it actually works amazingly well, and you can get a great game that way.”

Hecker’s social stealth game – the one that started a slowburn multiplayer revolution – has finally and unexpectedly taken the genre back to solo play, albeit in an unconventional form. “What I can do is feed you a replay at exactly your skill level instantly if there’s a lull in matchmaking, because I’ve got 2.5 million replays in my database,” he says. “It’s a huge timesaver, because I don’t have to have a spy AI now.” His only dilemma is whether or not to tell players. “Social stealth doesn’t require another person. But if you know you’re playing against a replay, you feel a little bit different.”

We can attest to that. Playing in daily challenge matches, we get the same stomach-tingling sensation of being out of the loop, looking in, straining not to miss a crucial detail. It’s a feeling akin to walking into a party late and trying to catch up with the conversation. But the frisson of besting a live opponent vanishes. “That word, ‘social’, has interesting psychological ramifications,” Hecker admits.

Whether it’s driven by AI or repurposed player data, the best social stealth is never going to be solely simulation. The genre comes to life when it invites the gaze of a second human being, or a third, or even a fourth. If triple-A developers want to embrace social stealth once more, they’d be wise to follow the example of the indies, and make room for the electricity that enters the room alongside another person. Even if that room happens to be a multiplayer lobby masquerading as a crowded dinner party.

This feature first appeared in issue #358 of Edge Magazine. For more great articles like this one, check out all of Edge's subscription offers at Magazines Direct.

Jeremy is a freelance editor and writer with a decade’s experience across publications like GamesRadar, Rock Paper Shotgun, PC Gamer and Edge. He specialises in features and interviews, and gets a special kick out of meeting the word count exactly. He missed the golden age of magazines, so is making up for lost time while maintaining a healthy modern guilt over the paper waste. Jeremy was once told off by the director of Dishonored 2 for not having played Dishonored 2, an error he has since corrected.