Why choosing to interrupt dialogue in Oxenfree makes the conversations feel natural

Night School Studio’s debut game begins with chatter. As the camera pans down to a boat, one of the teenagers on board, Ren, speaks in a monologue to his friends about their island destination. “Henry Fonda stationed here, I think, for a bit,” he says at one point, “Unless he was Navy...”

“Who’s Henry Fonda?” asks another character, Jonas. But Ren continues with his presumably unsolicited lecture: “And around Christmas time, this little breakfast place used to sell these amazing polar bear sugar cookies. Maaaaan, those were good.”

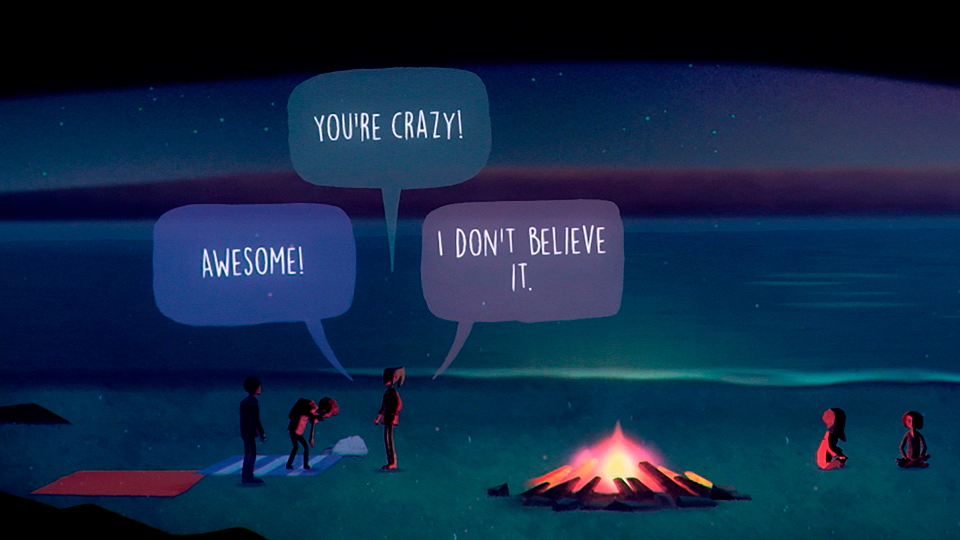

When Ren finally does wind down, he calls to the other person on the boat: “Alex. Hey! Still with us?” Three pastel-coloured speech bubbles appear with different dialogue choices, and you realise that this teenage girl with aquamarine hair is the player character. If you’re too slow to choose a response, you lose your chance. Of course, Ren picks up the slack: “So, Jonas, this is what I like to call a ‘trip’, this blank slate thing Alex’ll do sometimes.”

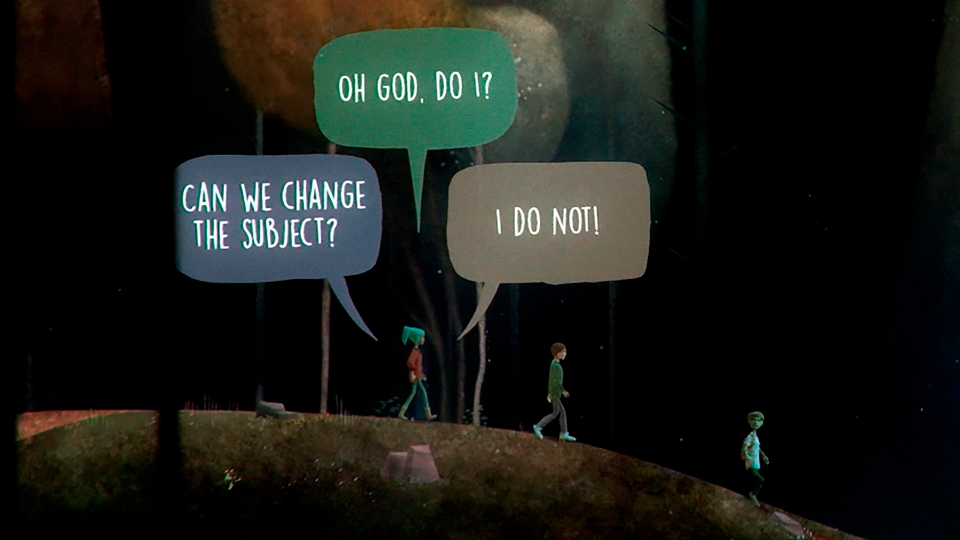

This intriguing exchange sets the tone for Oxenfree. Ostensibly, this is a supernatural mystery game, but it’s far more interesting viewed as a game about a group of teenagers, and thus about social dynamics. The developer has put an impressive amount of focus on in-game conversation – writing sprawling dialogue trees, letting you walk and talk at the same time, creating moments where two conversations happen at the same time – and it’s paid off.

Some players might hate the dialogue time limit, but it’s necessary in order to encourage interruption, which makes the conversations feel natural. Alex’s speech bubbles usually appear before her conversational partner has finished talking, and just as in real life a response will often pop into your head while you’re listening. Sometimes the speech bubbles disappear before the other person is done – if you’d wanted Alex to speak, you should have interrupted.

Real life interruption definitely has negative aspects (for instance, men are more likely to interrupt than women, and are more likely to do so in a conversation with a woman), but it’s a natural part of human interaction. Sometimes we do it so we don’t forget what we want to say. Sometimes we want to prevent a conversation from going down a bad path. Sometimes the other person is glad of the interruption because they were just talking to fill the silence. Oxenfree represents all of these eventualities.

The interruption mechanic is powerful for those moments when, as in real life, you make the conscious decision not to use it. At one point Jonas, who is Alex’s new step-brother, starts to open up about his past. You can interrupt, but I choose not to. In real life, if people have summoned the courage to tell me something emotional, I make a concerted effort not to break up the flow with questions or advice. I try just to listen.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

I interrupt people more than I would like. I’m working on it, and that’s part of growing up. Teenagers, as uncomfortable bundles of social energy still getting to know themselves, talk over one another all the time. In Oxenfree, how much each character interrupts or is interrupted is part of what defines them. Clarissa, who seems self-centred and may be insecure, talks over her friends frequently, despite having little to say. Ren’s shy crush Nona, on the other hand, is often cut off.

A friend of mine is writing a book about a teenage girl, and I know from talking to her that it can be difficult for adult writers to capture the way teenagers interact. Some people have compared Oxenfree to Life Is Strange, another narrative-focused game with a supernatural theme and a young cast, but the way Oxenfree’s characters speak seems much more natural. Their speech is peppered with “like” and “uh” and “you know”, and delivered by skilled voice actors (Ren annoys me whenever he speaks, but I’m pretty sure he’s supposed to). But most of all it’s full of interruptions, and of things inevitably left unsaid.

This article originally appeared in Xbox: The Official Magazine. For more great Xbox coverage, you can subscribe here.

Jordan Erica Webber is a talented freelance journalist with bylines on sites like GamesRadar+ and The Guardian, but there's a good chance you'll recognize her name from elsewhere. Jordan is the resident gaming expert on Channel 5's The Gadget Show, an arts and culture presenter for BBC Radio 4, and co-wrote an excellent book entitled 'Ten Things Video Games Can Teach Us (about life, philosophy and everything)'.