The story behind Grim Fandango, Brutal Legend, and more with Tim Schafer

Tim of legend

Tim Schafer and the entire team at Double Fine Productions must be feeling pretty good right now. With the first half of Broken Age now available and garnering the adoration of critics, point-and-click adventures are back in the spotlight after years of laying low. Broken Age has made quite the journey since its inception as a massively successful Kickstarter, and is a credit to those who helped make it. For Schafer, it's just the latest in a long and storied career in game design.

Schafer has been part of the gaming industry since the late '80s--and when you've worked on so many beloved games, you tend to pick up a thing or two from each project that'll make the next one run a little smoother. To find out more about the road leading up to Broken Age, I asked Tim about the important lessons he learned while making some of his most noteworthy titles (you can listen to the interview in full below). The answers may shock, delight, or terrify you--but they're all invaluable nuggets of wisdom for anyone who aspires to make great games.

It's tough being a tester, so give them a break

Before Schafer ensconced himself in the adventure genre, he had to cut his teeth on Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: The Action Game. "[LucasArts] hired a lot of us SCUMMlets--people who were going to work in SCUMM, who they also had no respect for--the grunts," recalls Schafer. "And they didn't have anything for us to work on right away, so they had us test." So Schafer was put to work on bug-checking a 2D platformer based on the third Indy movie. "It wasn't an amazing game," laughs Schafer.

"I [remember telling the programmers] 'Hey guys, I was doing that Walk of Faith, and I jumped off the letters into the abyss and the game crashed.' And all the programmers turned to me like they wanted to kill me," says Schafer. "It's important for everyone who works on games to spend a little time in the test pit, and know how it feels [to experience] the 'kill-the-messenger' mentality. Be nice to testers. Don't get mad at them--say 'Thank you' when they crash your games. 'Thank you sir, may I have another bug?'"

Don't be afraid of silly ideas, even if you think they sound goofy

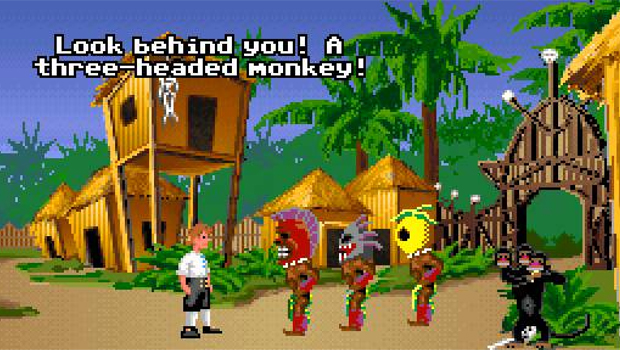

The Secret of Monkey Island was brought to life by three writers: Ron Gilbert, Dave Grossman, and Tim Schafer. "That was the first game I really really worked on. It was a lot of fun," says Schafer. "We'd just write in silly dialogue, and we thought it wasn't going to be used--we thought Ron would come in and write the real dialogue later. That allowed us to take a bunch of risks that we normally would've censored ourselves from." To Schafer and Grossman's surprise, Gilbert was happy to keep all the one-liners, puns, and Star Wars jokes in the game.

It even led to one of the most memorable scenes in the whole game, when Guybrush has to make three villagers look the other way. "We just put in this stupid dialogue line: 'Look behind you, a three-headed monkey!' That's just illogical, and therefore can't be in the real game! And Ron [said] 'No, no, that's great, we'll keep that!' I was like 'But no, that's so stupid! There can't be a three-headed monkey!'" Once Schafer saw the finished product, though, he remembers thinking "I can't believe I was ever afraid of putting in something [I thought was] too silly. The thing I learned the most on that game was from Ron, which was not to censor yourself so much, and not to be afraid of stupid ideas."

Planning is good, no matter what George Lucas says

Day of the Tentacle had all the zaniness of the first Maniac Mansion, with the added comedic benefit of fully-voiced dialogue. "Sometimes I refer to that as the last fun game I ever worked on, because it was the last time it was just easy," says Schafer. "We planned, and executed on the plan, and it was exactly the amount of time we thought it was going to be. And then after that, it was all just taking on these super ambitious games that were even bigger and scarier."

But a hitch in that straightforward development arose when George Lucas himself came to tour the LucasArts studios. "Day of Tentacle was the first time we had done storyboards; artists sketched out every environment in black and white with pencil," recalls Schafer. "We put them all up and planned every environment, and we were so proud of ourselves for being that organized. So we brought George in, and we showed him that. And he's like 'Yep. Can't make a movie without a script.' I guess that's what I learned. You can't make a movie without a script. Except for THIS IS A GAME. But stillit's important to plan, or [at least] try to plan."

Getting stuck in an adventure game isn't always a bad thing

The last big adventure game to use the SCUMM engine wasn't as wacky as its predecessors, but Full Throttle still told a unique, imaginative story, designed to be more cinematic and streamlined in the hopes that players would actually complete it. "A lot of people never finished adventure games," recalls Schafer. "You hit that puzzle you can't solve, and there's no Internet--you were stuck." But being temporarily stumped by an adventure game is just part of the process.

"I feel like there's good stuck and there's bad stuck in adventure games," says Schafer. "Good stuck is where you're like 'OK, I should be able to figure this out, but I'm just not getting it. What is it? I know it has something to do with that thingmaybe if I walk over here' Bad stuck is like 'Fuck. Shit. I've gone everywhere, I've used everything, I'm so mad at this stupid game.' It's not so much that [the player is] stuck, it's that they're leaving the fantasy world of the game. They're now thinking of the game in terms of 'What did this game designer intend? Maybe there's a bug here. I hate Tim Schafer.' When they get to that point, you've lost them--you don't want them to get that stuck."

Controls matter

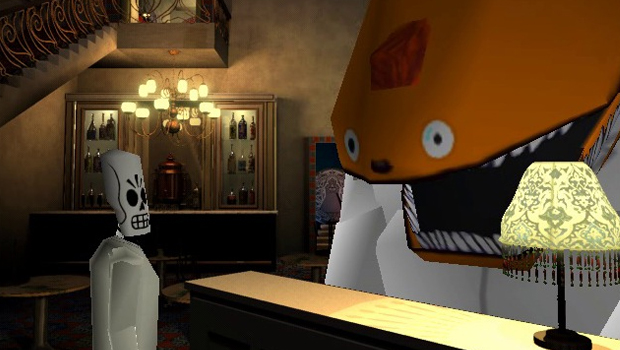

Grim Fandango was a massive undertaking in terms of scale--but it was also the proving grounds for adventure gaming in three dimensions. And moving through a 3D environment was a new challenge, which taught Schafer an important lesson: "Don't use tank controls." That said, the unwieldy method of movement was beneficial for navigating environments with multiple camera angles. "You'd walk down this hallway, and there'd be a low shot that looked all cinematic, and a top-down shot, and a sideways shot--but you didn't get disoriented, because you're just pressing forward relative to the character," says Schafer.

It's hard to blame Schafer for his conviction; games like Resident Evil and Tomb Raider were also doing it at the time. "But the thing that I wish we had done is put in some sort of point-and-click [method of control]," says Schafer. "There really wasn't any reason [not to]--I was just so excited to be moving into character-based game controls. But I see now: there's something special about pointing and clicking."

Publishers value profitability over creativity

Psychonauts is one of the greatest games ever made, but publishers just didn't see the value in it. "It came very close to putting us out of business," says Schafer. "The demos always went wellpeople would laugh and say 'This is great!'" Yet nobody seemed willing to take a chance on it. Schafer recalls one publisher (name withheld to protect the ignorant) who told him "This game is really, really creative. It's just too bad that people aren't going for creative stuff anymore."

"That's what I learned about the c-word: creative," says Schafer. "If you pitch a game to someone, and you hear the word creative, you're dead. [The publisher's] not going to sign it. You want them to hear the m-word, which is money." From that moment on, Schafer learned to play to his audience when pitching to corporate executives. "When I pitched games, I would emphasize the parts that sounded like money, and turn down the parts that sounded like creative," says Schafer. "Because [in a sense] you really are doing the creative [aspects] somewhat for yourself, and the people playing the game." So how would Schafer pitch Psychonauts if he could do it all over again? "It's basically Harry Potter," he laughs.

Be clear when communicating what your game is actually about

Brutal Legend threw many gamers for a loop. While players got the open-world, heavy metal-themed brawler they were expecting, some felt blindsided by the focus on elements from real-time strategy. "Brutal Legend was a very important lesson in how to message your game properly, so people know what they're expecting," says Schafer.

"A lot of this gets blamed on our publisher, EA, which isn't really that fair," says Schafer. "Our first publisher, Vivendi, definitely said 'We are not going to mention RTS, ever.' EA didn't have a problem mentioning it, but they definitely wanted to emphasize the action part of it." That kind of messaging seemed to counter what Brutal Legend was at its core. "The whole point of that game was that it was inspired by Herzog Zwei, for Sega Genesis," says Schafer. "The single-player part of the game was added later, to tutorialize the multiplayer part of it. I still vouch for that game, and believe that it's fun--but we didn't message what it was well enough, and we didn't tutorialize it well enough in the [campaign]."

Popular opinion can teach you a lot about your own decision-making

Every year, Double Fine hosts its own private game jam: Amnesia Fortnight, a two-week whirlwind of productivity, where the team splits into groups to create a miniature game. And those prototypes often balloon into full projects; Amnesia Fortnight is the way games like Costume Quest, Stacking, Iron Brigade, Sesame Street: Once Upon A Monster, Middle Manager of Justice, Hack 'n' Slash, Spacebase DF-9 came to be. "We've always enjoyed it, because it's a break from what we're doing," says Schafer. "Amnesia means that we forget what we're working onand we're going to work on totally different stuff for two weeks. That short amount of time forces you to just focus and not [make] too ambitious of a game design."

But not every game can make it, and whittling the projects down can be a challenge. "There's always been this troubling thing about trying to pick who lives and dies," says Schafer. "Now, we do it open to the public, and they all vote. Which is really interesting, because they pick different things than I might've picked." Spacebase is a recent example; its popularity opened Schafer's eyes to the gamers that love creating their own moments and scenarios, particularly in open-ended games like Dwarf Fortress and Prison Architect. "Amnesia Fortnight being public means it's no longer limited by my intelligence," laughs Schafer.

Sometimes, the things you wish you cut end up being your audience's favorites

If you haven't played Costume Quest, you should do so immediately, because I'm about to spoil one of the funniest bits. As you're strolling door-to-door in search of candy, you come across a rascal dressed up as a banana, who blurts out a line straight out of Arrested Development: "Like the kid in the $600 banana costume is going to follow the kid in the $20 costumeC'MON!" It's hilariously unexpected, and it almost didn't make it into the game.

Schafer recalls telling the team that "Comedy is not just making references to other things!" Luckily, he eventually had a change of heart. "We [ended up leaving] it in there, because I thought about all the Monkey Island Star Wars jokes that we made," says Schafer. "And for so many people, it was their favorite line in the whole game. I'm glad I didn't cut that line."

Designing a game around an existing IP is a lot trickier than it sounds

To date, Sesame Street: Once Upon a Monster is Double Fine's only licensed game--and for good reason. "It's harder to work with other people's properties, even if they're great," says Schafer. He'd always been opposed to doing a licensing deal--but Sesame Street's mission of enriching kids' lives, instead of trying to grub money from the, was worth an exception.

"It was great to be a part of that," says Schafer, "but it was hard to solve problems when we couldn't change the essential nature of the characters. Like, 'No, Cookie Monster doesn't do that. Elmo never uses pronouns. Grover never uses contractions.' You can learn these rules, and that's fine. But when you're making up your own world[anything can] make sense in your world, because you're creating it. It's a lot easier."

Kids will play your game in the most unexpected ways

Happy Action Theater (and its pseudo-sequel Kinect Party) are all about being playful, capturing the simple excitement of seeing yourself on a TV screen and adding in plenty of comical props. It's the perfect kind of game for a kid to play around with--but they may not always do what you expect. "There's a way you think your game is going to be playedand then kids will do something completely different," says Schafer.

The primary example is the memorable lava stage, where molten magma floods the on-screen floor. Schafer assumed that children would use it as a prompt to play Hot Lava, leaping between pieces of furniture to avoid the fiery ground. "That was the design use of that activity," recalls Schafer. "But kids did [the exact opposite]--they jumped in the lava and laid down, so they couldn't see themselves on the screen. And they'd just giggle, like [it was] the funniest thing ever.'" That led to an additional design, where those who immersed themselves in the lava could throw fireballs when they reemerged. "So what I'm saying, basically, is that children are the future," Schafer says with a smile. "Teach them well, and let them lead the way."

Getting people to crowdfund your game has as much to do with presentation as the actual product

When Schafer and co. came to Kickstarter with an idea for a new-age point-and-click adventure, they asked for $400,000 in funding. What they got back was a cool $3.3 million, making it one of the most successful Kickstarted projects of all time. "We're in this brand new territory, with having backers and having transparency," says Schafer. "Having backers watch everything, watch you designing your game, and cutting things, and moving things aroundthey're partaking in the discussion, and they hear about what we're thinking as we make decisions." It's also key to recognize that non-backers will be much more skeptical of schedule changes, because they are being updated on the game's creation every step of the way. "Also, 90,000 people are hard to embargo," laughs Schafer.

So what's the secret to smashing your funding goals? "I think to have a successful Kickstarter, in general, you just need to have a good storyan interesting person doing an interesting thing in an interesting way," says Schafer. Your project has to capture the imaginations of prospective backers. Schafer uses his own mindset when backing other projects as an example: "I can make this art happen that wouldn't happen without me."

Splitting your game into two parts definitely has its advantages and disadvantages

Broken Age went through its fair share of delays during its development, ultimately leading to a tough decision: split the game into two parts. "The advantage of splitting Broken Age in half is that people get to play it now--you don't have to wait till whenever we finish Act 2," says Schafer. And its creators benefit just as much as the players. "We got a lot of feedback that we can use in Act 2. [Plus,] the team gets this little motivation of people liking the game and it getting good reviews, and that helps us finish Act 2."

But making half the game publically available means that planning ahead is crucial. "The downside is, if I thought of something while making Act 2Act 2 isn't totally finished, the design is roughly there, but as we implement we always change the design," says Schafer. "And if I get this idea like 'Oh my god, I need this character to be foreshadowed in Act 1,' it's going to be hard. I could still stick it in there, because it's going to update on Steam--but I'll feel weird about that, because a lot of people played it already. We had to work really hard to design Act 2 and know what we were doing [in the long term]."

Feelin' Double Fine

I don't know about you, but I sure as heck feel educated now. The full interview with Tim Schafer as is below, which holds the answers to bizarre questions such as: What did Tim Schafer do when he met Tim Curry? Which iteration of Guybrush is Schafer's favorite? What's the happiest time of the year at Double Fine?

If you're still on the fence about Double Fine's latest, be sure to read our Broken Age review. For more developer (and Tim Schafer) history, check out The first games of legendary developers.

Lucas Sullivan is the former US Managing Editor of GamesRadar+. Lucas spent seven years working for GR, starting as an Associate Editor in 2012 before climbing the ranks. He left us in 2019 to pursue a career path on the other side of the fence, joining 2K Games as a Global Content Manager. Lucas doesn't get to write about games like Borderlands and Mafia anymore, but he does get to help make and market them.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!