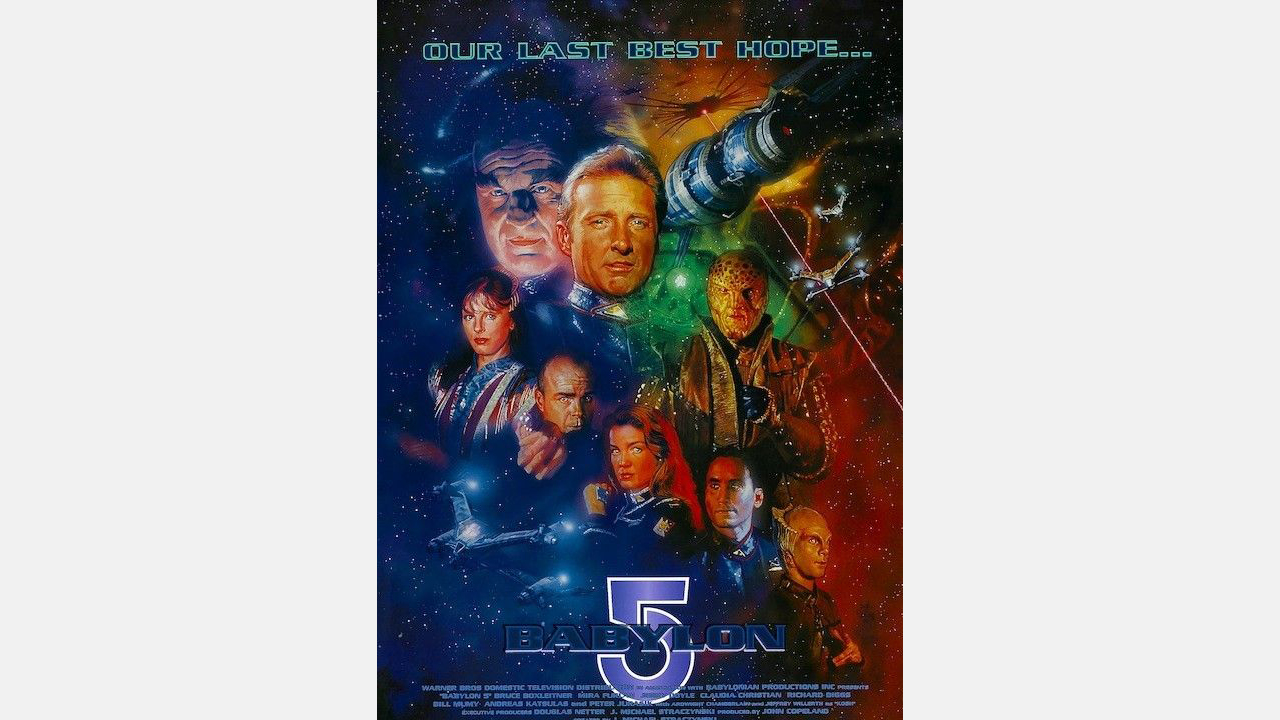

JMS revisits Babylon 5 on show's 25th anniversary

Light years ahead of anything else on television then.

2019 was the 25th anniversary of the seminal sci-fi show Babylon 5, and in many ways it presaged what was to come in their future/now our present.

No, we're not talking about laser guns and spaceships. Not yet at least.

We're referring to the format of a multi-year television series with a broad overarching story told over several years, several seasons, and several episodes. Now, it's the standard for everything from Game of Thrones to Breaking Bad, and even to Star Trek: Discovery.

In 2019 Babylon 5 creator J. Michael Straczynski (better known to fans as JMS) spoke with Newsarama about the early days of the series, fighting to get the show (and the format) over with TV executives, and the history of one space station all alone in the night.

Newsarama: JMS, you've called Babylon 5 a "novel made for television". What made you want to tell the story on television, at a time when the serial format was the norm? And what kind of push back did you receive initially?

J. Michael Straczynski: The idea of saying “This is gonna go five years, and we’re done” and “It’s gonna have the structure of a novel," and that we’re building toward a conclusion really had never been done.

But I’ve always been kind of a contrarian, so when someone tells me, “This hasn’t been done” or “This can’t be done,” my first instinct is to go off and do the d*** thing.

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

The idea back then was that when the end of the episode comes up, you hit the reset button and start the next one fresh. Maybe you might get a two-parter, but that’s about it. Stations and networks felt strongly about that because they didn’t think the American public had the attention span to cover more than two episodes. They also argued that when shows go into syndication, individual stations don’t pay attention to broadcast order, so you can’t rely on them to get it straight.

I called a bunch of stations and said, “Do you guys ever get things out of order?” They said, “No, we always go exactly the same, off the numbers on the tapes” because they had to track that for residuals and royalties. “So we know exactly what order to put them.”

I went back (to Warner Bros.) and said: “Well, you’re wrong. PS: You’re wrong. They then flipped to saying,“ No other American space-based science fiction series other than Star Trek has gone more than three seasons in over twenty years, you’ll be lucky to get two seasons, let alone five. Let it go. It’s too risky.”

My feeling at the time was that yes, no one has done it before, but the worst that could happen is I’ll fail. And they can’t kill you for that, they can’t eat you, they can’t put you in TV prison, so why not take a chance and do something that hasn’t been done before?

Nrama: So it was just as much their concern for syndication (rerun) logistics as it was for Babylon 5 being long-form storytelling?

JMS: It was all those. The syndication issue I overcame quickly. Their concern about an audience having the attention span for multi-year arcs I still had to prove to them. And over the course of the five years we got of that show we did that.

The good thing is that we were often the ‘orphan child’ of Warner Bros. There was benign neglect that - under other circumstances – let us get away with things that we probably couldn’t have done otherwise. So when we showed we could do exactly what we said we could do, they ignored us. After season 2 episode 2, they stopped giving us notes. We were kinda left to our own devices, and that was the good thing about it.

We were able to write and foreshadow things in season one that paid off in season five at a time when they thought you just couldn’t do that. And of course now everyone is doing five-year arcs. You can’t walk into a TV network now and pitch a show without someone saying to you “What is the long view? What happens in season 2, with season 4? How’s it gonna end?”

I had a meeting at a studio a while back, and was pitching a show with a five year arc. The executive in charge said, “People come here all the time and say ‘I wanna do five year arcs’ and they never pull it off. What makes you think you can do it?”

“Because I invented it, mofo.”

And yet, in its time, fans would be worried about the show getting canned after each season. Between Seasons 4 and 5, the show switched networks - it always seemed down to the wire.

Our mandate with the PTEN network was that every year, we had to show a profit for the network. And every year, we showed a profit (even though on paper we’re still in the red as far as profit definition is concerned, which is why, to this day, I’ve never made a dime of profit on Babylon 5. We’re still allegedly 30 million dollars in the red).

But despite hitting our objective, there was always this strange attitude from Warner Bros. that still persists to this day toward Babylon 5. See, PTEN was created by Warner Bros. Domestic Distribution, the guys who handled selling reruns of previously made Warner Bros. TV shows to syndicated stations. They didn’t do original programming, they just sold what was already there.

PTEN said, ‘We’re gonna pick our own shows (for new content),’ and Warner Bros. TV was…I wouldn’t say locked out, but they were sort of minimized in the process. And a lot of those guys took that very personally.

Babylon 5 was even further outside the group because all the other shows - Time Trax and the rest of them - had been developed in-house at Warners. We came in from way out in the outside. We were kind of the out-house program. So there’s always an internal resistance to Babylon 5in Warner Bros., which led to constant uncertainty for us. We were always the last ones to get the pickup. Other shows would get advance pickups, but there were times where we got it so late that we were already behind schedule to meet airdates.

The fourth year, Warners just told us flat out that we’re not coming back: the PTEN network itself was shutting down, so they said to wrap it up, which we did. To their surprise we pulled off the move to TNT situation for the fifth season, which allowed us to finish our story.

Nrama: When it comes to the appeal of long-form storytelling today, how much does streaming play into it? That wasn’t around at the time of Babylon 5.

JMS: Netflix internal surveys can tell what you’re watching and how far you get in it, and those figures suggest that the average viewing of a series that’s downloaded all at once is two and a quarter episodes. They’ll watch the first two, see how the cliffhanger resolves itself, and stop there. That lends itself toward stories that rely more on long-form, incremental stories than something where all the data has to be crammed completely into a pilot episode.

For instance, when we did Sense 8, had our pilot been aired just by itself on a traditional network, people would have been so confused by it that they would’ve just said forget it. But because all the episodes were online at the same time, people could look at the first one and say "Okay, I don’t get this, but let’s keep going just in case."

So certainly, the capacity to watch a lot of episodes at the same time has made it easier to do stories that run through the entire season.

Nrama: These were early shows that picked up the long-form when streaming was still yet to explode?

JMS: Correct. Ronald D. Moore sent me a copy of the Battlestar: Galactica pilot script to look at with an eye toward using our multi-year structure, and Damon Lindelof later told me that they borrowed our structure straight up for Lost. Those two shows further crystallized the five-year arc structure, and within fellow geek circles, that really made a huge impact even though initially you didn’t initially see it happening in the mainstream shows.

Once those two became hits, the other producers looked at what made them different than anything else, and they said these long-term story arcs must be it, so let’s do that over here.

From there it gradually became more mainstream, and now we have binging where you’re watching the entire season in one night, which is great.

Nrama: Production-wise, were there any new challenges you guys had to figure out for Babylon 5, given there were no previous models to work from when it came to long-form TV storytelling?

JMS: We were kinda making up the rules as we went. There’s a huge learning curve attached to that.

The hardest part was figuring out how to layer in the key events across five years, what parts have to go in where. Adding to the complication, we had to balance out the actors.

Some actors were hired for a full 22 episodes per season, some were hired for 16, some were hired for 11, some were hired for 8. So I had this spreadsheet in my office of what episodes we could put actors into. And an actor I might need to have for a particular arc piece might not be available to be in that episode. So do I move the arc piece earlier, or pay the extra fee to have the actor come in? Or give the arc slot to someone else? It’s like this giant LEGO set. But the difference is the pieces are always moving.

Nrama: That’s interesting to hear - that some of the actors were only hired for a certain amount of episodes per season.

JMS: Some shows just buy all the actors for all the episodes produced because it’s simpler. They don’t have to worry about who’s available or not. But we were a very, very low budget show - I think Star Trek, at that time, was about $1.5 million an episode, and we started out at around $650,000. So we had a lot of burdens that other shows don’t tend to carry.

The first season was primarily stand-alones with a few arc episodes. I realized that I couldn’t do a heavy arc approach at that point because the audience wasn’t ready for that yet, they didn’t have the language for a five-year arc, so I would have to slowly acclimate them. But I could start laying in little clues that will initially seem just like ordinary character scenes but which would be seen later as having great significance.

So when the audience saw that paid off a year later, they realized in retrospect that it was a clue to something bigger, that it wasn’t just conversation, it was foreshadowing.’

Because this was also new to the cast, sometimes the actors needed more information. There’s a scene where we show G’Kar and Londo strangling each other in a flash forward. Peter Jurasik (Londo) came to me and said, “What’s the context of this? Can you at least tell me what it is?” Because it was way down the road. I gave him the information and his eyes went as wide as poached eggs.

But by the same token, I didn’t want to tell them too much, because that risks having them play the result, rather than the process.

Nrama: The budget constraints, if I’m remembering correctly, was a factor in being the first show to heavily use computer-generated visual effects. And as a result, Babylon 5 had a lot of spectacular space shots and battle scenes -

JMS: When you haven’t got a lot of money, you have to be smart and figure out solutions that will often lead you to being innovative. We couldn’t afford to do models and miniatures on a budget that was $600,000 an episode. It would’ve just blown the budget apart.

But CG at that time was very new. It was mainly used for transitions and title cards, that kind of thing. When we said we were gonna base an entire show on this, Warners was very hesitant. They were saying “You know, we don’t think this is gonna work out, it’s gonna look like shit.” And we had to really work hard to convince them.

Once we started doing it, we were able to bring color into the universe. So instead of everything being white ships, firing at each other in close range, which makes no sense at all, you had these ships that were beautiful, colorful, that could be thousands and thousands of miles away from each other, engaging in combat.

We really structured the battles in ways you couldn’t do with models, and were able to show real combat techniques and strategy and planning.

Nrama: Another aspect that makes Babylon 5 stand out - to this day - is how it acknowledged sociological themes like culture and religion with a sincere, optimistic view.

JMS: People often don’t know how to approach those subjects without seeming preachy, or corny. It’s much easier to be skeptical about all that stuff, to be down, pessimistic, or dystopic. To show the nobler aspects of the human spirit, and say that there is something in us that is greater than the sum of our parts is really hard to pull off without being goofy.

But I come from a background of being a Psychology major and a Philosophy minor in college, was deep into religious studies, and I came out of a Catholic background (but I got better). So I’m not afraid to touch those things.

The Star Trek universe seemed to say that for us to go into the stars, we have to leave behind important parts of ourselves, the good and the bad: our vices, our avarice, our commercialism, but also our faith and our beautiful fractures. And I thought, no, we will still carry that with us.

When settlers came to the Americas from Europe, they didn’t leave behind their culture, they brought it with them. It gave them continuity in a new world. So it was important for us to show that continuity. We see religion, alcoholism, drug abuse, all the things that ennoble or plague us now carried into the future. You bring the beauty as well.

In the show, Sinclair says that we had to go to the stars, or we would lose William Shakespeare, Marilyn Monroe, Buddy Holly and Lao Tzu. There’s as much beauty in the human race as well as our least noble parts. So I wanted to show us taking that with us when we go into the stars.

Nrama: Do you find it ironic that sci-fi is something that networks often feel doesn’t work on TV, yet it’s what breaks a lot of ground when it comes to the way stories are told and produced?

JMS: The problem is that the networks don’t often understand science fiction. They consider it niche programming. They worry that it’s too smart, or that it’s too cold to the touch, or it’s just propeller-heads who tend to watch this stuff. So whenever a science fiction show gets canceled, the networks are quick to say that science fiction doesn’t work. Which they never say if a cop show gets canceled.

Science fiction has always been a ghetto genre as far as the larger world is concerned. I think gradually, that’s starting to change.As the old guard is retiring, we’re seeing a new bunch of guys coming in who are more savvy in that category. I go into meetings now with networks and they’ve seen Babylon 5, or Jeremiah, or Sense 8. They’re more aware of science fiction so there’s a warmer reception to it now than there was even five years ago.