Kerbal Space Program 2 is more accessible than its predecessor, but no less punishing

How a landmark space sim is leaving its home solar system behind for new horizons

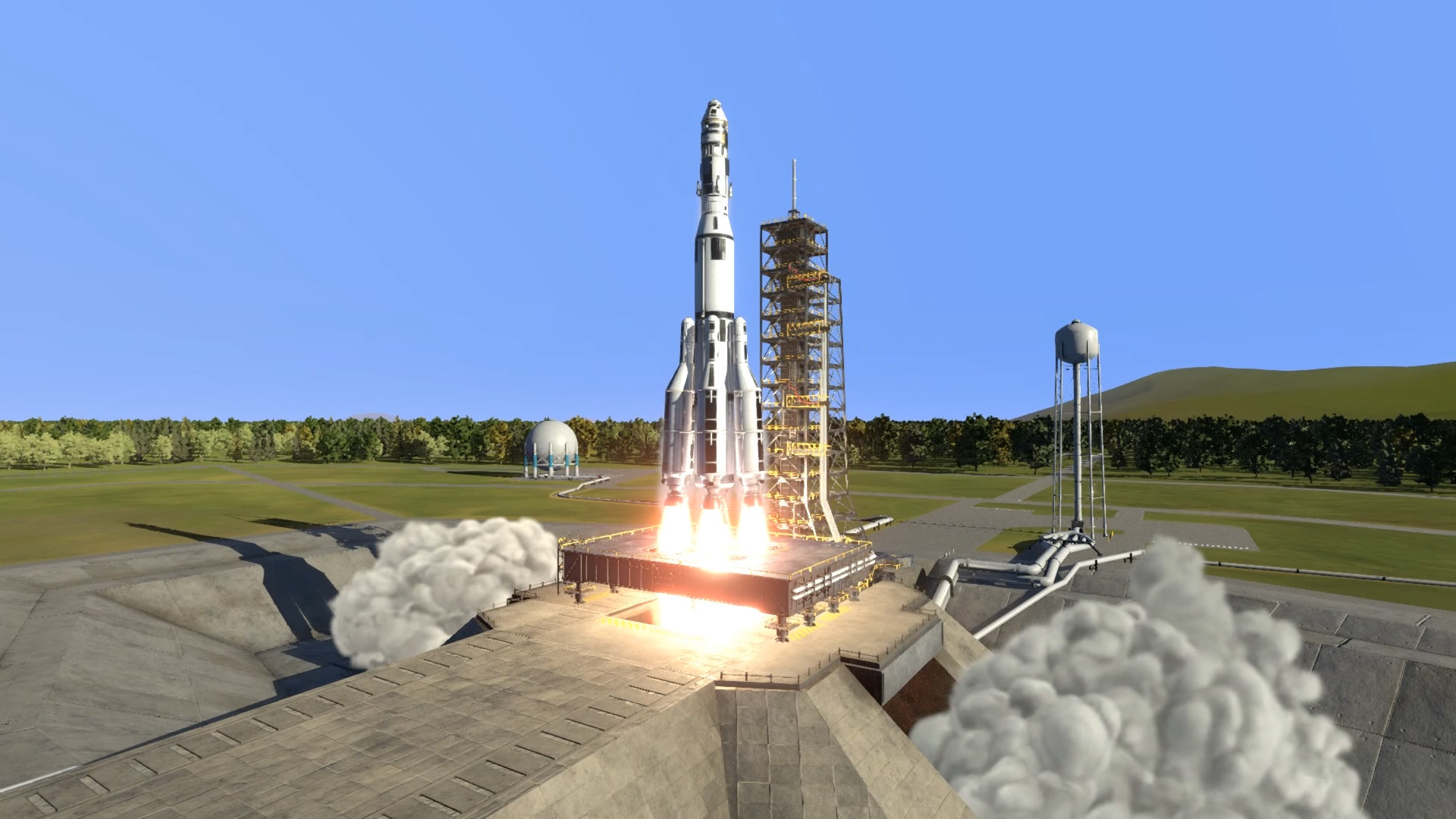

Dozens of attempts were made by many Kerbal players before one reached the moon. Heaven knows how many tries it will take to reach another solar system. In development at Planetary Annihilation studio Star Theory following the departure of series creator Squad, Kerbal Space Program 2 raises the stakes like only a NASA-endorsed space sim can. You can now build colonies on other planets, allowing you to shift your launch facilities away from the debris-strewn grasslands of the Kerbal homeworld. You can also build orbital stations, bolting together zero-G dockyards for ships too vast to build on the ground – vessels with the fuel capacity required to travel to another star. Everything looks rather spectacular even in pre-alpha, with more elaborate geometry, textures and lighting than in the 2011 game, and everything is, once again, very fragile. Place a coupling awry and that hand-crafted spacecraft is just an SFX set-piece waiting to happen.

As ever, the goblin-like Kerbals themselves take such mishaps in their stride, grinning idiotically while their rockets teeter over mid- launch. Newcomers to the Kerbal series may find the possibilities more intimidating, but creative director Nate Simpson promises us that, for all its fresh complexities, this will be a more accessible simulation. "We think some of the original game's hardcore image is undeserved, because the core concepts aren't actually as impenetrable as they might seem," he says. "What we've learned from iteration around the control process is that a lot of these core concepts can actually be taught very intuitively through animation. When these things are presented visually, they're a lot easier to digest."

This feature first appeared in Edge Magazine. If you want more like it every month, delivered straight to your doorstop or your inbox, why not subscribe to Edge here.

Hence the new animated tutorials for features such as the navball, which shows ship orientation, and hence the revised UI. While still labyrinthine, the construction screen now sports filters and colour-coding and a plan view to help players align boosters. (Advanced tricks include the ability to create separate versions of a ship simultaneously then combine them.) As regards flight, some hotkey functions have been moved into the UI, while other elements have been cleared away. "What we've seen from our early user testing, is that this is actually a game that is quite accessible, without us having to dumb down the core game," Simpson says. "We've basically turned that first-time user experience from a cliff, where you have to go watch YouTube videos to understand what's happening, into a ramp."

The focus is on improving the user journey

It remains a steep slope, nonetheless. The aspiring Kerbal astronaut's greatest foe is once again the physics simulation, which is "mostly unchanged". As before, each of the planets (Star Theory has yet to give a number) has a sphere of gravitational influence which determines the physics interactions within. This may disappoint seasoned players hoping for an upgrade to 'n-body' physics, in which all masses affect and are affected by their neighbours continuously, but Simpson says a degree of simplification is healthy.

"If you take the Kerbal system from the original game, and you apply n-body physics to that, that solar system disassembles and starts to fire moons at planets," he says. "In general, I think that's where we come up against this game being a game – if you bring in n-body physics, you do get some cool phenomena like Lagrange points, but you also sacrifice a lot of predictability. A real n-body system will evolve over time, and it might have dire consequences for your save game, if you're playing over thousands of years and building up an interstellar civilisation."

"If we succeed in making the first-time user experience better there will be more people landing on the moon"

Nate Simpson, creative director

Many of the old technologies are back, too, albeit "in more beautified form" but there are plenty of new toys, from extra ship core sizes to fresh kinds of propulsion, including a drive that works by detonating nukes behind it – not something you should try near a starbase. Star Theory is still working on the supporting economic systems, but the key currency for tech is once again science. There's also the enticing prospect of Kerbal sex – or, as Simpson puts it, "growth events" – which aim to encourage players not to fast-forward their projects quite as often. "It's essentially what drives population increase locally at individual colonies. As you achieve things in the games, Kerbals celebrate by... increasing their population. And that's a great way of decoupling colony progression from time zoom, because a lot of time-based mechanics are completely undone by the zoom – I can just sit there and activate 10,000x zoom and things happen automatically. So this is a way for us to couple player progression to growth."

As for the architecture of those colonies, you'll want to play it safe to begin with, sprinkling a few habitats across a nice level area, but overreaching is much more fun. "Surface colonies really can turn into a game of Tower Of Goo," Simpson says. "We are simulating physics for those too, and there are so many goofy things you can try. Personally I love the idea of building just the longest possible cantilevered structure out over the edge of a canyon, and then a landing pad on the end of that, and trying to diving-board that thing. There's a lot of domino-style stuff you can get into. It's very Kerbal."

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Venturing offworld

Orbital space stations are naturally less constrained – though still liable to crumble like wet candyfloss when you dock with one a little too firmly – which "means you can build vehicles of essentially arbitrary scale, as big as your computer can handle, probably." This greater capacity is vital because interstellar vehicles guzzle up fuel more or less constantly, accelerating for the first half of the voyage, then flipping around to decelerate for the second.

If tours of other solar systems and offworld dockyards are Kerbal Space Program 2's more immediate draws, its magic ingredient may prove multiplayer, which is the reason Star Theory has overhauled so much of the original game's engine. Simpson can't share much on the subject, but suggests that this feature as much as the clearer interface will help the game expand its audience (another benefit of the overhaul is that modders have more options to play with). As regards reactions to the sequel in the existing Kerbal playerbase, he says that "their and our instincts are well- aligned" so far, for all the usual fan misgivings about designing for accessibility.

"There's been a certain cachet to getting deep enough into Kerbal Space Program that you can land on the moon. If we succeed in making the first-time user experience better there will be more people landing on the moon, and I guess if you think of that as currency, we're devaluing it by letting more people accomplish that. What's more exciting to me, though, is that the members of the community who do have that experience are joining us in this larger mission of introducing this universe and all these concepts to a far larger number of people."

This feature first appeared in EDGE. For more excellent articles like the one you've just read, why not subscribe to the print or digital edition of EDGE Magazine at MyFavouriteMagazines.

Edge magazine was launched in 1993 with a mission to dig deep into the inner workings of the international videogame industry, quickly building a reputation for next-level analysis, features, interviews and reviews that holds fast nearly 30 years on.