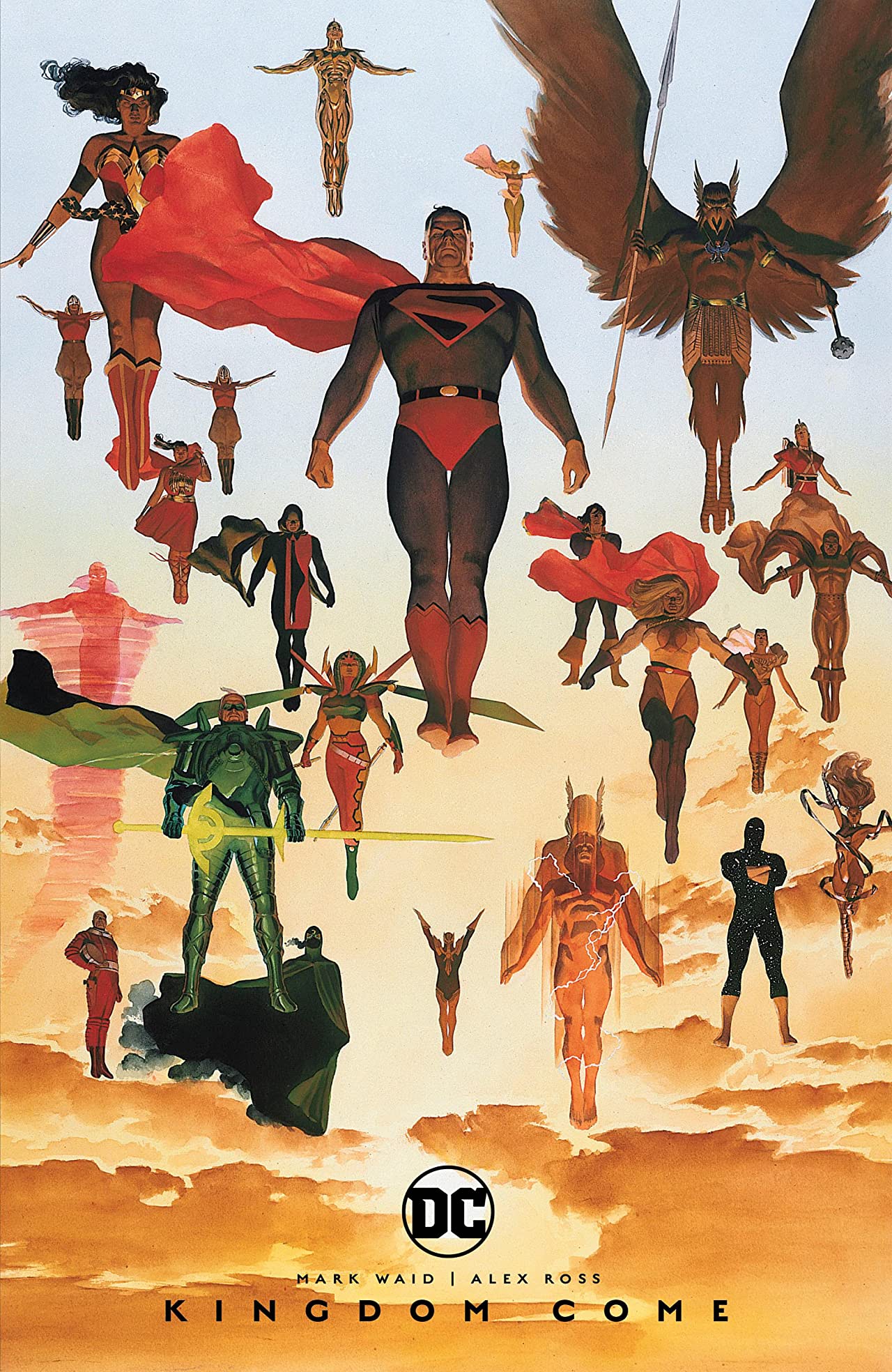

Best Shots review: Kingdom Come "a DC fan’s playground brought to realistic life"

Looking back on DC's seminal Kingdom Come

Alex Ross and Mark Waid believe in superheroes. They believe in the goodness and purity of the costumed heroes from their childhoods. And it is more than believing that Superman and Wonder Woman are good; it is superheroes as a concept that they believe in and hold to a high moral standard. These heroes teach a moral code to exist by, a heroism that should be aspired to; superheroes should be the best of us. Kingdom Come presents their thesis statement about these beliefs and explores what happens when characters, creators, and readers abandon the aspirations promoted by them.

Written by Mark Waid

Art by Alex Ross

Lettering by Todd Klein

Published by DC

'Rama Rating: 6 out of 10

With Superman living in self-exile at the beginning of this story on a farm just like the one he grew up on, Ross and Waid show us that the world has moved beyond an age of superheroes. You could argue that true superheroes ended with Watchmen, Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, and all of the deconstruction of superheroes that found inspiration in Alan Moore, Dave Gibbons, and Frank Miller. A new one began a few years later with the creation of Image Comics where Rob Liefeld, Jim Lee, and all of the original partners created their own darker and grimmer version of superheroes for the closing decade of the 20th century.

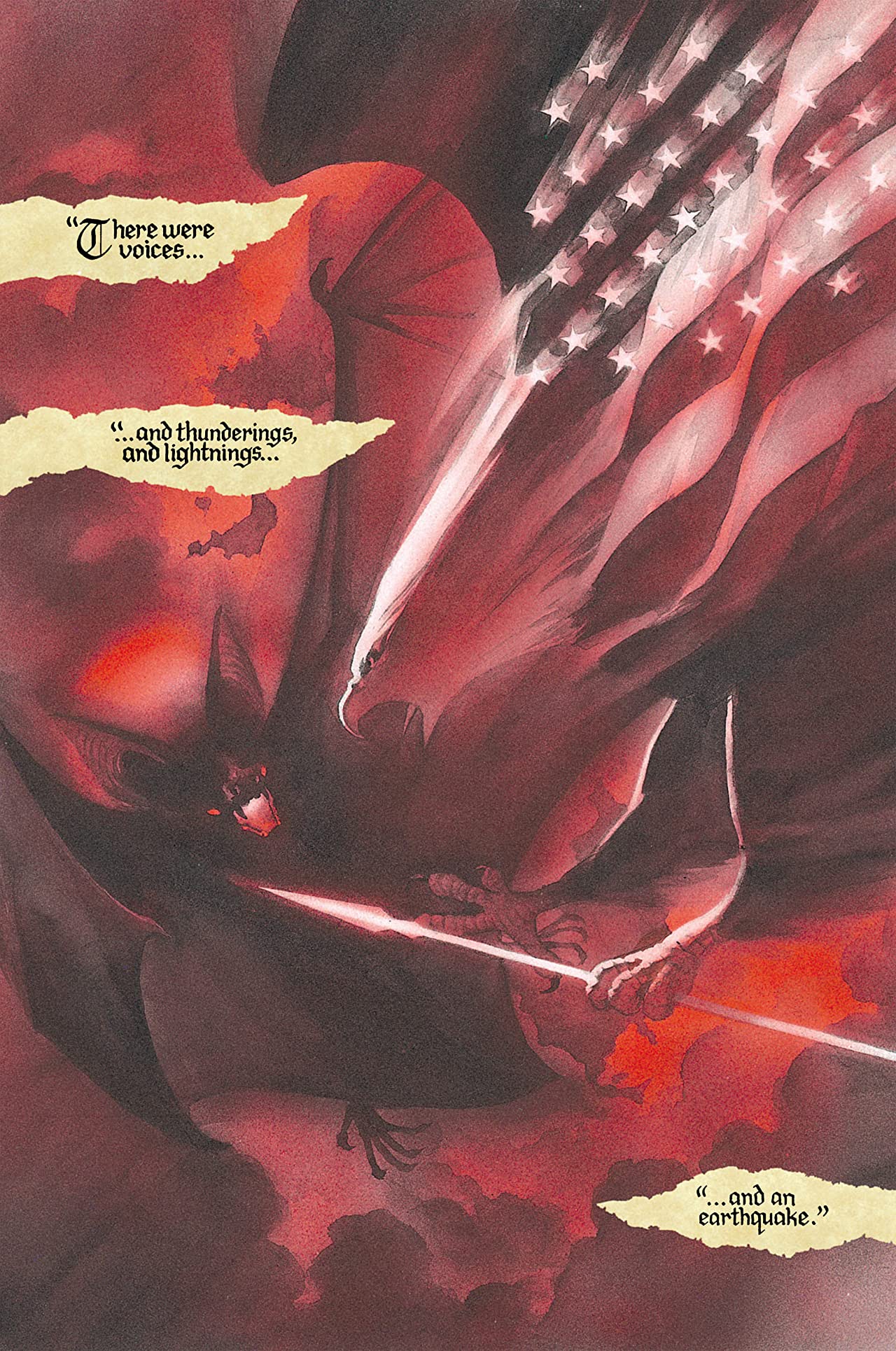

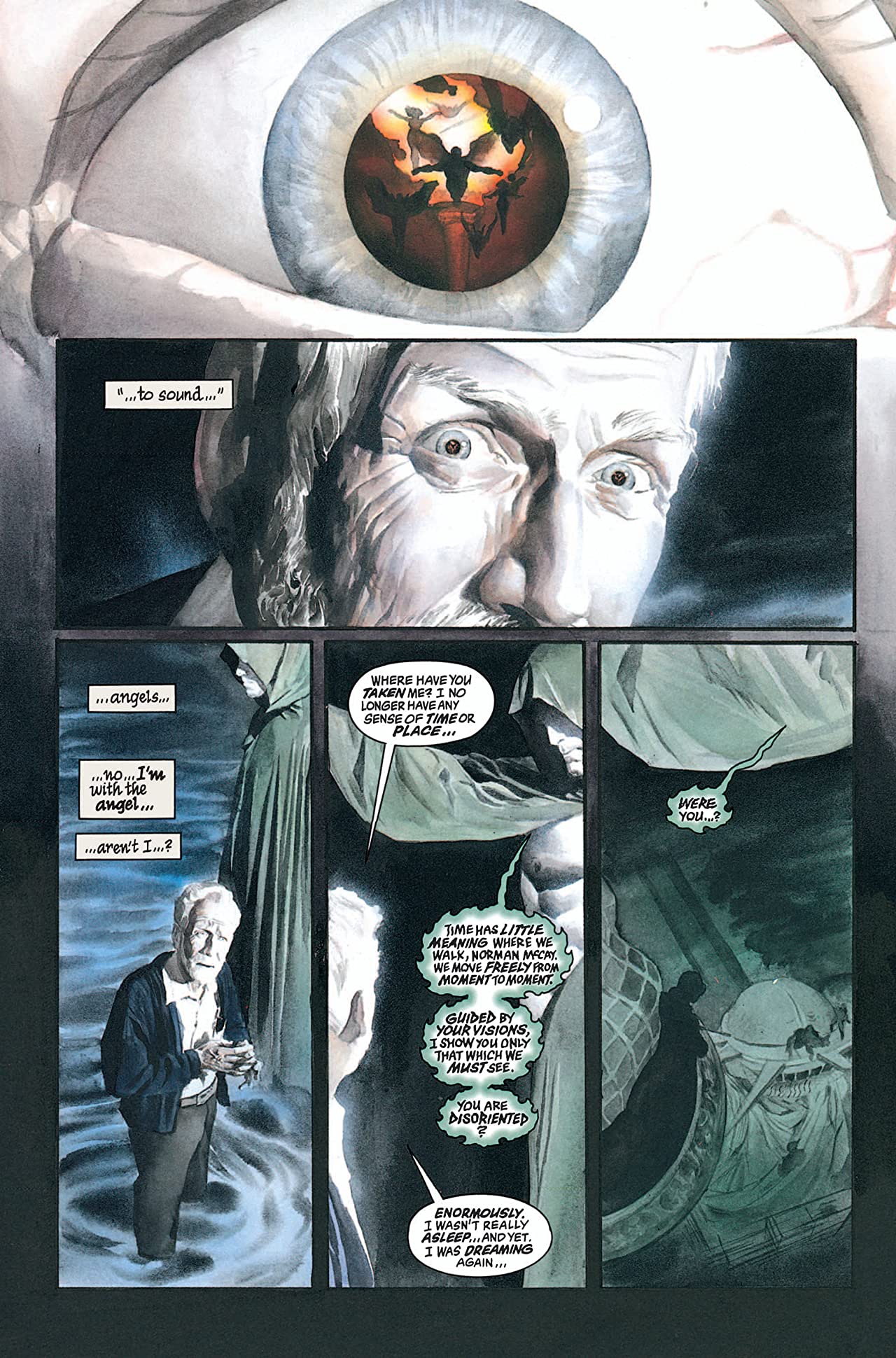

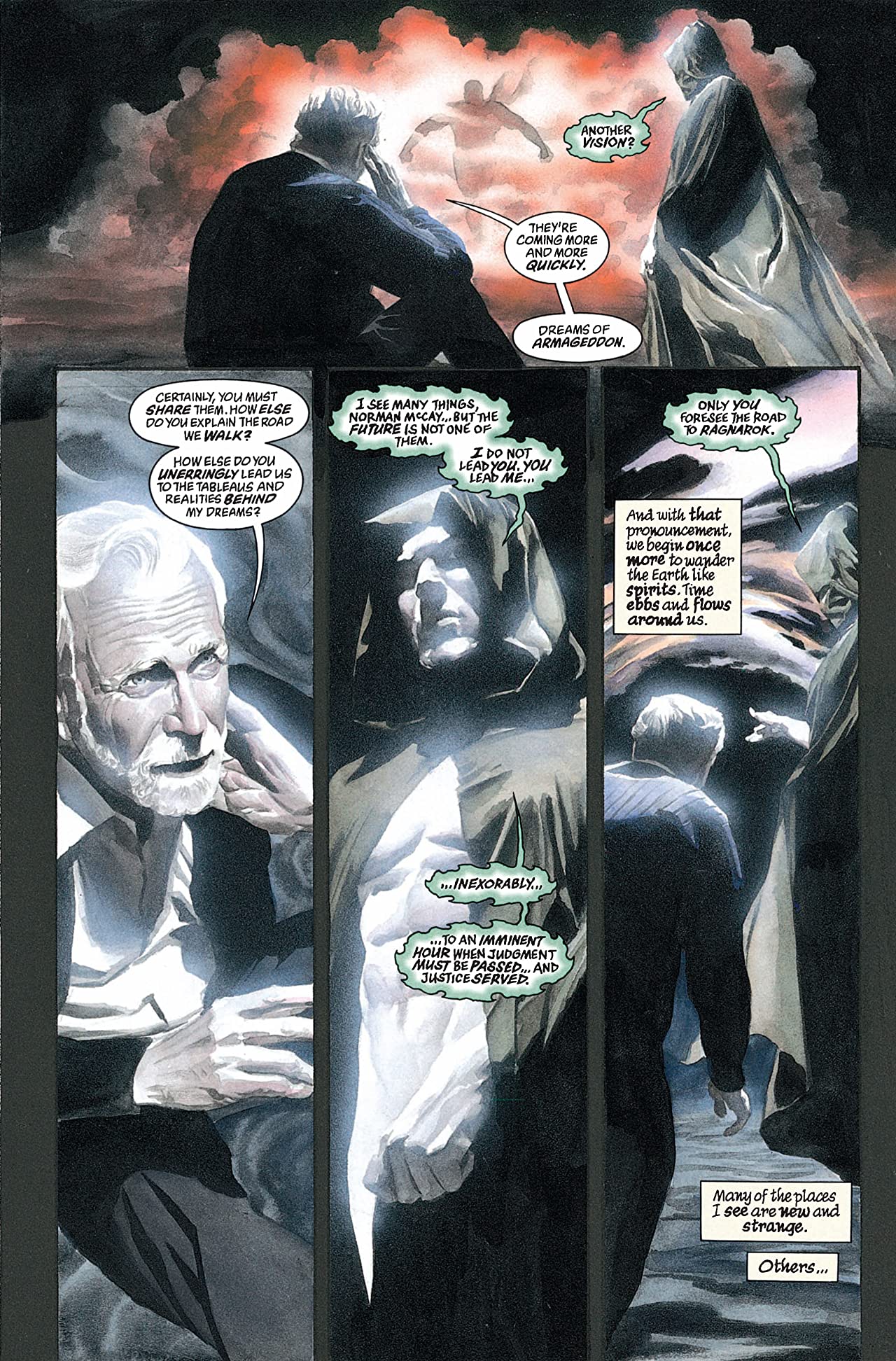

Kingdom Come opens with fire and brimstone. It opens with lost preachers and New Testament prophesies. Through a dying Wesley Dodds, the Golden-Age Sandman, and Norman McKay - an old church pastor who finds himself going through the motions more than believing in them - we’re introduced to a world that the super-heroes have largely abandoned. After a personal tragedy, Superman lost his faith in the humanity that he thought he was an intrinsic part of. Like Superman, Batman has retreated from the world but made Gotham City his own personal crusade, creating a police state that only he could think was a new utopia. Wonder Woman, an ambassador for peace, tries to re-ignite the heroes’ crusade, believing that only Superman can provide the inspiration needed for this new generation of super-heroes and rekindle the flame in the older generations.

So one thing you need to know about the '90s was that nearly everything popular in comic books was either an Image book or it was a Marvel or DC comic trying hard to look like an Image book. Even that didn’t always work, as this was the time that Marvel took legendary Hulk and GI Joe artist Herb Trimpe, put him on a Fantastic Four comic, and made him draw like he was a Rob Liefeld wannabe. It is in this creative environment that Ross and Waid conceived Kingdom Come, and you can see them waging a one-sided wrestling match against the types of comics that Liefeld, Lee, and everyone else at Image were creating and guiding. Kingdom Come is a reaction to the '90s from a sensibility of what a superhero was as if the concept of a superhero was perfected and frozen in the '50s.

As Superman abdicates his responsibility in the world, a new generation of powerful men and women fill the void. With new names like Von Bach, 666, Minotaur, and Swastika, these characters were a new, younger breed of superhero, fighting just to fight than for any sense of truth, justice, and all that jazz. They were the forgotten kids of the missing role models.

Ross’s realistic portrayals of these gods and legends try to bring them down to earth, to give them a humanity that maybe he felt was missing from them at the time even as he celebrates the physical perfection of the characters. His painted realism is still a realism defined by older super-hero comics. His storytelling reflects a DC classicism, taking the best of artists like George Perez and Jose Luis Garcia Lopez to shape this world of sorrow and recriminations. His figures are strong and heroic. They bear the weight of their powers and responsibilities. Even Norman McCay, an old man past his prime, carries a nobility as he bears witness to this history.

Reestablishing this nobility to all of the classic characters is Ross and Waid’s self-appointed mission. Part of the price of admission to Kingdom Come is believing that the characters need to be reconstructed, to be reformed once again to be the heroes of myth and legend. One of Ross’s biggest challenges is to get you to believe in the inner struggles of these characters and he just isn’t able to live up to that challenge.

Comic deals, prizes and latest news

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

Ross cannot get out of the mode of showing the inner might of these characters enough to show their inner struggles. Sure, his Superman is often grim-faced and his Batman is always plotting, but that is the total range of emotion that he can give them. Waid does not help out here as his sole idea of these characters’ development is 'more grim' and 'more conniving.' While Ross can bring a weight of visual realism to this story through his painted artwork, he is just not able to reveal the characters’ motivations and challenges. His figures go through the motions of the story without ever inhabiting the heart and soul of the story.

While it’s not full-on uncanny valley territory, Ross’s dedication to realism creates a mask over the whole story. With his painted style that owes far more to Norman Rockwell than to any comic artist, Ross’s work tries to signify its importance but is never able to really bring these characters to life. It is easy to ooh and ahh over the painted importance of this story but in comic books, there is a thrill to seeing the world in a way that we never can in real life. By trying to depict reality, Ross brings all of these magical beings down to our levels and that just never really works.

Luckily for Ross, Waid is all about playing to the melodrama in his writing. Through the dialogue, he never lets you forget the drama that these characters are experiencing. Superman is sad, Wonder Woman is angry, and Batman is just fed up with everything. That’s the level of characterization that Waid can muster up in his writing. For as much perceived importance as Ross’s artwork gives the story, Waid’s writing plays to a base level of the characters, good guys and bad guys who have to fight because that’s all they can do. Fighting is the only way to resolve any disagreement. Where’s the fun of seeing Superman and Lex Luthor fight again when we can see Superman and Batman fight again. In this comic book, they continually use their fists instead of their voices to solve their conflicts.

With their combined encyclopedic knowledge of DC history, Ross and Waid give the story some heft as they do everything they can to make this about the legacy of all of these old stories that came before them. Their reverence to the nature of these stories is aimed toward the stories that they grew up reading. Their Superman is equal parts George Reeves and Max Fleischer cartoons, broad-shouldered and barrel-chested. In fact, everything in the story turned around on Superman and went bad when he let his hair grow out into a ponytail, a distinct reference to the mullet-haired Superman era of the '90s that happened right before Kingdom Come was originally published. So the message here is that the old stories are good and the new stories are bad.

Ultimately, we’re asked to judge the worthiness of these classic superheroes through our surrogate into this story, Norman McCay. Modeled after Ross’s own father, McCay moves through this story playing the dual role of conscience and witness to these gods on earth, the old reliable characters, and the new out of control generation of powerful children who are their own straw man arguments for Waid and Ross. The odds are stacked against the new, young characters. Even in 1996, there was no way that a character named 'Swastika' was ever going to be a good guy. Through McCay’s eyes, we see all of these characters at their worst but are called to remember the classic heroes at their best.

Ross and Waid have this trust that through this story, we’ll remember these characters as fondly as the creators do and have the same fond sentiments for them. As the creators are trying to react against what superheroes have become in the '90s, they’re actually contributing to the degradation of their legacies. The period of superhero deconstruction that started with Moore and Miller is alive and strong in Kingdom Come. it is just that a fresh new coat of paint is put on the story, a more nostalgic coat than many of the classic deconstructionist stories ever had.

Superman is not a hero in this story. Neither is Wonder Woman nor Batman, they're more like the kids that they’re reacting against, lashing out at a world that they think is stacked against them. In this comic, they’re not fighting for you or me. They’re not fighting for the American way, peace, or even justice. They’re fighting just to be superheroes, to have the power and authority that comes with that. All they want is some kind of relevance in this new age, and that’s what Ross and Waid want for their icons. In the end, everyone fighting for a status quo that rejected them. From Ross’s realistically painted work to Waid’s ability to work in the most arcane details in the book, Kingdom Come is a prestigious book that spends its whole story reminding you of its prestige.

And maybe the best thing that happens in this story is that mankind gets fed up with their so-called betters. As the superheroes are locked in their Grand Guignol battle in the heartland of America, the world powers decide that they’ve had enough and try to end all of the superpowers with three nuclear warheads and to jettison these beings that have no relation to any real humanity. It is a drastic move but it is understandable for mankind to want to re-establish their place in this world. Get rid of all of the children and those who are acting like spoiled children. And it almost works but enough heroes, including Superman, scatter like cockroaches when the bombs drop. Some heroes like Blue Beetle are killed in the blast so there are some stakes to these events after all. But after reading this story, who actually cares about Ted Kord as anything more than a Batman stooge? I don’t know, maybe you like Batman stooges.

With a Superman pushed over the edge (you can tell because his eyes in these final pages are glowing red,) it's up to our stand in Norman McCay to step in and remind Superman that he’s not a god; he’s just a man. Superman is just a human being like you and me, as so many Superman stories like to remind us. All of the superheroes are human though everything about the story is how they are so much more than human. At no point do Ross and Waid want to wrestle with choices or stakes in this story. Up until the end, this isn’t a story about humanity and superheroes; it is about superheroes and more superheroes but let’s toss in the U.N. and nuclear detonation to try to remind everyone that Superman and Wonder Woman are just like you and me. Maybe all they need is just a hug and everything will be better.

In the end, McCay has one last opportunity to question the Spectre. "All the sins have been exposed, Spectre. Tell me, in the end… who do you punish? Who is responsible for what has happened?" and the answer turns out to be no one. The Spectre, literally a spirit of vengeance, says "No one…" when asked this question. No one in Kingdom Come has to bear the weight for a portion of the American midwest becoming a nuclear wasteland; they’ve got powers to clean that up. No one has to be responsible for the destruction and the death that came from those battles. As long as we’ve all learned our lessons, everything is hunky-dory in the end. Everyone gets to go back to their lives and be the most perfect version of themselves that they can be. Live and let live.

A grand, fun book full of silliness and a childlike understanding of right and wrong, there is a fanboy-ish glee to joining in on the game that Ross and Waid play here, picking apart all of the chicken-scratch easter eggs in the background of nearly every page. For any DC fan, there’s a lot of text, metatext, and subtext to chew on and even more when you want to bring in comics as a whole into a metatextual reading. But in the end, the story collapses under its own weight. Arguably, this is a story of the new generation versus the old. New characters versus old characters. New creators versus old creators. New sensibilities of what heroes should be versus the old, tried, and true sensibilities about what superheroes should be. And Ross and Waid fixed the argument from the very beginning so of course, the old ways won.

Kingdom Come is a What If? story. What if our heroes were not as great as we thought they were? It’s easy to get swept up in the spectacle of Ross’s painted images that give this story a feeling of grandeur and importance. It’s actually fun to get lost in all of the minute details that Alex Ross and Mark Waid toss into the story, in trying to pick out just who all of these background characters are. Flipping through the book is practically a DC fan’s playground brought to realistic life. But that’s all the joy found in this story where these iconic characters just do nothing except bicker and fight among each other. Like Norman McCay, we’re left to ask "who’s responsible?" And to get the answer that no one is just isn’t the say the world works except in the pages of superhero comics where everything will be forgotten by the next issue.

Kingdom Come is one of the best DC comics stories of all time.

Scott is a regular contributor for Panel Patter, GamesRadar, and Newsarama, covering comic books since 2002. He specialises in comic book reviews, and also runs the blog I Lost It At the Comic Shop.