King's Field: How FromSoftware’s first game started a cycle that's still in motion

From King's Field to Elden Ring, there's more to the cycle of mythology than you may have realized

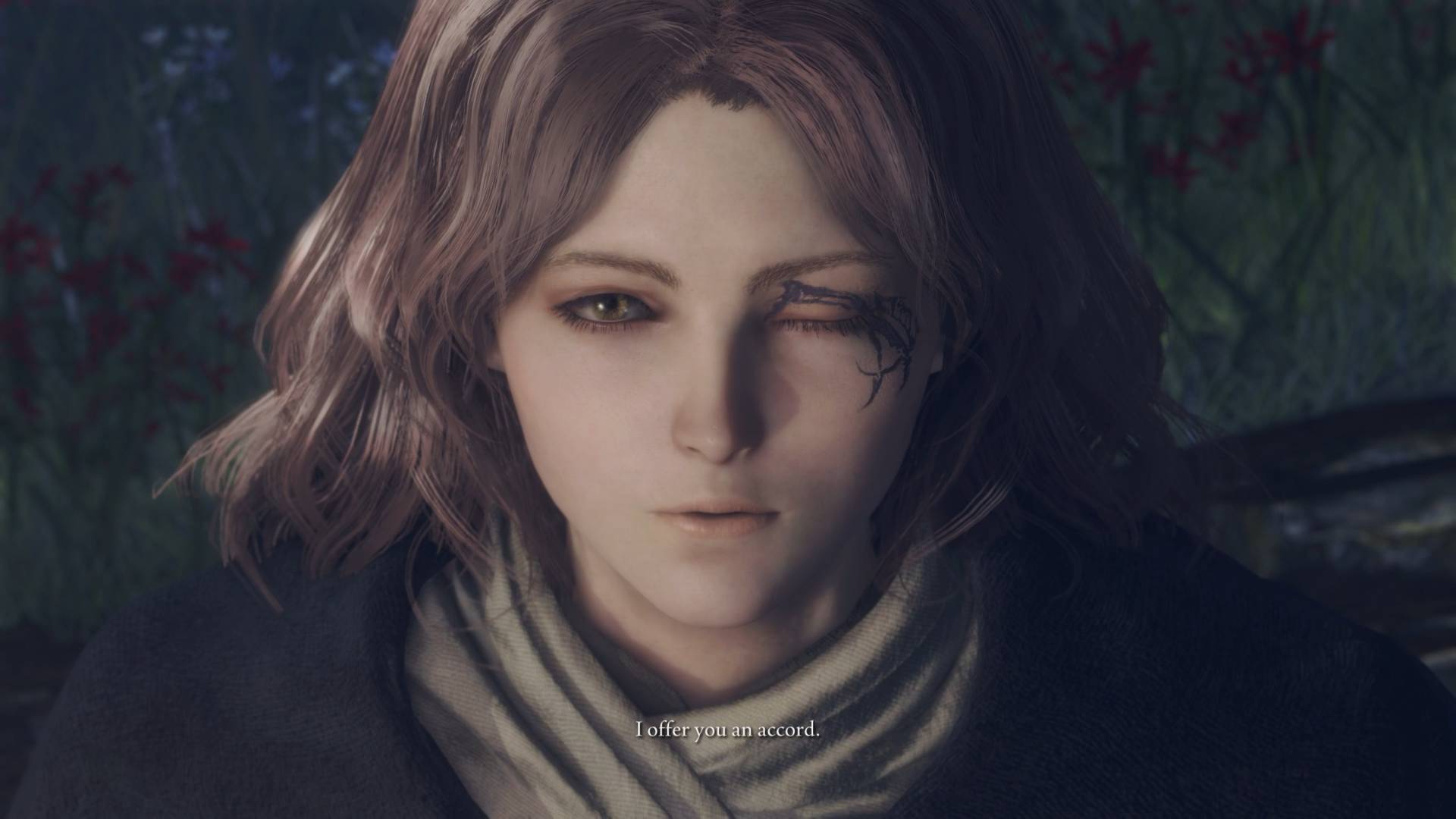

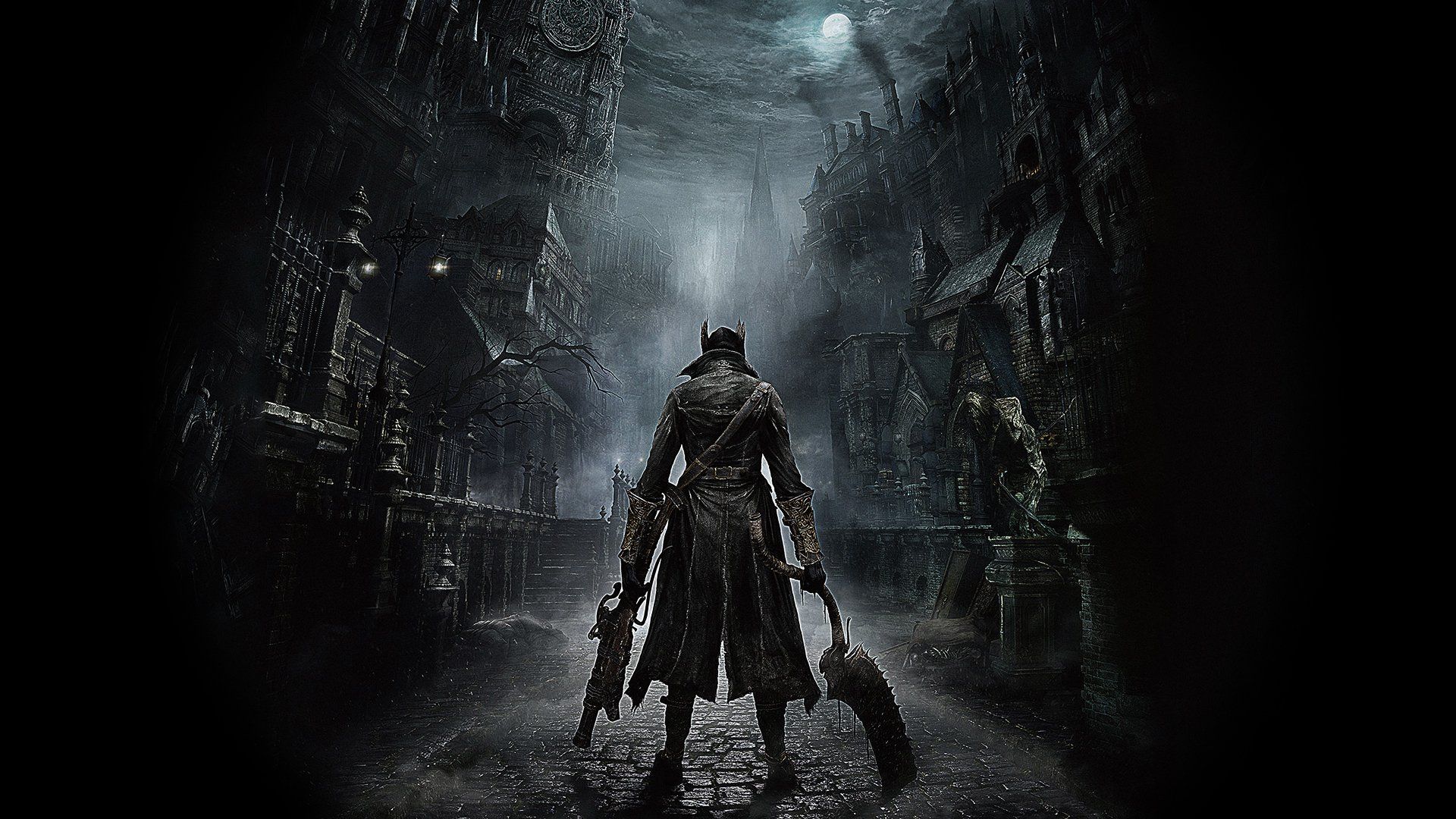

Cyclical mythology is one of FromSoftware’s favourite things. Not quite as high on the list as poison swamps, obviously, but it’s certainly up there. Dark Souls, Bloodborne and, of course, Elden Ring all have themes of history repeating, tales beginning and ending and beginning again with only minor variations. Indeed, the ultimate decision made by the player is usually whether to continue a stagnant cycle, transcend it, or burn it all down. It’s a challenge: do you trudge forward in familiar mediocrity, or take a gamble on the unknown?

Elden Ring marks a significant point in From’s own cycle, as a game developer. Not an end, you would hope, but a pinnacle, certainly in terms of ambition and scope. And so we find ourselves drawn back to the beginning of the tale that led here. For many, this would be Dark Souls, or maybe Demon’s Souls – the label we apply to this particular flavour of action RPG, after all, is ‘Soulslikes’. But the reality of the matter is that this cycle began many years earlier, in December 1994.

A first-person RPG for the original PlayStation, King’s Field was released less than a fortnight after the console’s Japanese launch. The first videogame from a company originally known for making productivity software, King’s Field was actually From’s second game development project. The first, a 3D exploration game featuring robots in a subterranean maze, was targeted for PCs but abandoned when the team realised that the desktop computers of the time weren’t powerful enough to realise their vision. When Sony’s console was announced, From decided to pitch a new game made for it, and produced King’s Field in just six months.

Heavy lies the crown

This feature originally featured in Edge magazine's issue #377 - subscibe here!

At the time of its release, King’s Field proved divisive, with criticisms levelled at slow movement and combat, frustrating difficulty, and general obtuseness. Despite a mixed critical reception, however, the game did well enough to spawn three sequels, two spinoffs and a commercially released construction kit. It’s easy to draw a family line from here, through Shadow Tower, Eternal Ring and, vitally, Demon’s Souls, to the release of Dark Souls – and those original complaints about apparent hostility towards the player aren’t the later games’ only inheritance.

You’re dropped into the world of King’s Field – a dark fantasy setting with a distinctly medieval European flavour – after a brief introduction that provides a little context. The manual offers a few more hints about where to go and what to do, but otherwise you’re left to find your own way. As you would expect given the age of the game, this world lacks the exquisitely designed architectural landmarks of FromSoftware’s most celebrated works. Instead, the way forward lies through twisting tunnels of pixelly grey and brown, with the occasional change in texture providing precious little sense of location. You’re provided with a compass at the outset, and a map is obtainable before leaving the first of five dungeon levels, but these tools are far from infallible, and many tunnels and pathways lead outside the bounds of the map entirely.

Hidden doors and illusory walls abound, leading to moments reminiscent of the game’s first-person contemporary, Doom, inviting you to slide along walls, face pressed against the stone, mashing the use button in an effort to find secrets. Depending on the route you take in King’s Field, it’s entirely possible that your first encounter with an enemy will take place behind one of these disguised entryways, whereupon you will be swiftly dispatched by an aggressive skeleton and deposited back at the start of the game.

"Like so much of King’s Field, this combat is a clear blueprint for the Souls games to come".

While there’s no helpful ‘You Died’ message, it’s the first of many moments that evoke the modern Soulslike and lay bare the common threads that run through FromSoftware’s catalogue. Combat in King’s Field is simple: one button is for melee attacks, one for casting spells. Shields exist, but only as passive sources of defence stats. There are no defensive moves to make, other than simply stepping out of range – a difficult task, with the player character’s tank-like movement further compounded by a control scheme designed for an age before dual analogue sticks. You turn using the D-pad, while one pair of shoulder buttons is used for strafing and the other to look up and down when necessary.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Weapon swings are achingly slow, and the pace of melee is further impeded by two power bars – one for weapons, one for spells – that are depleted on use and then quickly refill. Attacks made without a full power bar are weakened, while spells are restricted entirely. The result is combat that favours timing and resource management over raw speed: baiting attacks, darting forward to deliver a blow, timing the swing so that the weapon impact disrupts the enemy’s own offensive, then retreating to a safe distance; carefully circling to avoid fangs and blades while waiting for the moment to deliver your own attack; using quick, weak ranged attacks to create openings for decisive melee blows. Like so much of King’s Field, this combat is a clear blueprint for the Souls games to come. The power bar is a stamina bar in all but name, and even stats on the weapons and armour feel familiar, with physical damage being divided up into slash, chop and stab types.

Pushing further into the game reveals more similarities. NPCs are scattered throughout the world, acting as merchants and quest givers, or simply providing helpful clues to guide you on your journey. They’re also the primary delivery mechanism for plot, one small snippet of monologue at a time. While nowhere near as convoluted or cryptic as the stories of Dark Souls or Elden Ring, familiar themes are present, with tales of corrupt kings and fallen dynasties. Ancient dragons may or may not also be involved. The opening crawl describes a hero of ages past who is prophesied to come again, while the game ends with the protagonist – one Jean Alfred Forester – becoming king after felling the monster the previous one became. Cycles within cycles, history repeated.

Royal bloodline

There is one major FromSoftware ingredient missing from King’s Field, however – and one that isn’t necessarily obvious when actually playing the game. In 1994, Hidetaka Miyazaki was still a decade away from joining the company. With so much Soulslike DNA already in place here, it may seem strange that the man so strongly associated with the genre had no hand in making the game. Miyazaki’s predilection for poison swamps is a longrunning source of amusement, yet here they are, already present and correct, albeit in prototypical form – pools of noxious green sludge are one of a number of often unavoidable traps and pitfalls that dot King’s Field’s dungeon environs. None of this diminishes Miyazaki’s achievements later, but it is a helpful reminder of the limits of auteur theory.

King’s Field established another cycle for FromSoftware. Thanks partly to the studio’s low profile, the game did not arrive to any great fanfare, a factor in initially poor sales. It took word of mouth for the game to find its audience and eventually become commercially successful enough to warrant a sequel. While it’s hard to imagine the same situation occurring again today, following the enormous success of Elden Ring, there were echoes in the release of Demon’s Souls. The PS3 game’s quality wasn’t universally acknowledged on its release, its reputation growing more widely over time to the extent that the 2020 remake became a focal point for the launch of a new PlayStation era.

As FromSoftware has risen to become a superstar game studio, it would be natural to expect its games to become more accommodating. Instead, its refusal to please everyone has become a hallmark. Elden Ring has been criticised for the ways in which it fails to cater for players in the manner expected of modern triple-A titles. Design that is compellingly mysterious to one player can feel overtly hostile to another. Should that, then, be the next frontier for From to conquer? Is it finally time to smooth off those rough edges?

Of course not. Of all the repeating threads of FromSoftware’s story, the most vital one is the rejection of industry trends in favour of making games the team is so evidently passionate about. Modern games have a tendency to be focus-group tested and fiddled with to the point that their character and charm is obliterated. At the same time, there are many games that, while falling short of the commercial expectations set out by their publishers, contain innovative ideas that never get the opportunity to be fully realised. Plans for sequels are cancelled, teams disbanded, studios shut down. And that’s all assuming the game gets released in the first place.

King’s Field is not a good game by any modern standard. In some ways it wasn’t at the time of its release. However, the ingredients for greatness were there – and, though it took decades, FromSoftware was allowed the time to refine the recipe. If there’s a lesson here, it’s that while stagnant cycles should be brought to an end, those that can continue to evolve, growing from the remains of their predecessors, need to be nurtured. There is no guarantee of excellence, but it is only through this process that true legends can be forged.

This article featured in Edge magazine's issue 377 - subscribe to Edge for more articles like this one and much more.