Gaming shadows have come a long way. In the N64 days you were lucky to have a shadow at all. Characters that did were cursed with a shapeless blob at their feet - a potato’s shadow no matter how complicated their form. When the blob embraced realism and sprouted limbs, shadows became quite the talking point, a graphical trick to rival shimmering water and realistic beard hair.

Above: It takes some peering, but the main character is about to jump over a gap near the middle

Granting shadows the equal rights of their corporeal casters was never enough, however. In Lost in Shadow a shadow runs free of its body. Yes, that’s right: this shadow isn’t attached to a character. You are the shadow boy, a gamboling wisp confined to the backdrops we’d usually sprint past. Just how did he lose his body? Guillotined from his feet a la Peter Pan? Perhaps he lost his fleshy self in a freak threshing accident? Answers, we’re told, lie at the tip of a huge tower (the game’s working title was The Tower of Shadow). But first he has to scale the thing, climbing from rustic ruins at the base toward clanking industrial regions at the peak.

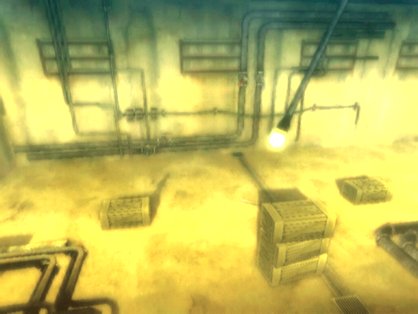

As a shadow you prowl the murk cast by traditional platforming scenery up front. Piles of crates become dark pillars. Pipes cast snaking networks of misty lines. The threat of falling is elegantly handled: topple into an area of light and the shadow evaporates into nothingness. Large dark areas are equally dangerous – fall into a mass of shadow and you’re engulfed. After 25 years of escaping nondescript death pits – where do those holes go in Super Mario Bros? – seeing these ideas addressed with an artsy explanation makes a pleasant change.

Although relegated to the background, the boy can shift solid objects by meddling with their shadows. Pulling the shadow of a switch manipulates the switch itself, raising all kinds of terrifying questions about whether or not society is actually governed by shadows and not vice-versa. Levers open doors and, in one section, set a multi-pronged mechanical contraption in whirring motion. As the machine rotates, so does its shadow, shifting inky walls from your path and aligning new platforms.

Far smarter than using shadows to move the ‘real’ world, and the crux of Lost in Shadow’s design, is the influence of shifting light sources on the shadow realm. If the light moves, the shadows dance. To prevent mind-melting we’ll opt for a basic scenario first: a swinging bulb will bend a crate’s shadow left or right – your atypical moving platform. Drop a bulb towards the floor, however, and the shadows stretch. When your shadow becomes drawn out and heavy, the boy won’t be able to jump as high. Pull the light away and our hero becomes more of a speck, springing around like New Super Mario Bros’ mini-Mario.

Your fate’s not always in the hands of swinging light bulbs. The boy is joined by a Navi-like sprite, cloyingly named Spangle. Fluttering in the foreground, Spangle affects light sources, deliberately shifting the landscape in the boy’s favour. Changing the angle of a light source will raise and lower platforms or align disjointed chunks of scenery into bridges and stairs. When the duo encounters fixed light sources, Spangle can break the scenery – bending metal bars, for example – to cast the required shadows.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

The developers complicate things further with the introduction of shady assailants. The boy is plagued by a larger shadow, pursuing him around the tower and calling forth smaller flecks of darkness to bring him down. Swordplay keeps them at bay, but considering how easily you can cast a shadow gun with your hand, wouldn’t this be a better option? The image of the willowy shadow boy armed with a sword recalls PS2’s similarly shadowy ICO – a game Hudson Soft borrows several bottles of dreamy atmosphere from.

Lost in Shadow also echoes WiiWare stalwarts LostWinds and NyxQuest, both in the remote pointer/analogue stick controls and in a slight sense of, well, slightness. As clever as mind-bending light-bending seems, do Hudson have the ideas to fill an entire retail release? If they find a puzzling depth to go with the visual depth this could be a 2D must.

Dec 10, 2009