GamesRadar+ Verdict

A game of inspired highs diluted with pedestrian lows. Worthy, but achieves less than its true potential.

Pros

- +

Wonderful, evocative world-building

- +

Intelligent, genuinely mature storytelling

- +

Excellent craft on show in isolated areas

Cons

- -

Too much indistinct, slight, repetitive busywork in mission design

- -

A few interesting systems that become moot in their execution

Why you can trust GamesRadar+

You know that kid at school who seemed disruptive and lazy, but then a few years later it turned out that s/he was actually some kind of genius, and just wasn’t being well-served by the comparative mundanity of the classes on offer? And was actually capable of brilliant things, given the right encouragement, but some of the other kids still had their doubts regardless? That’s Mafia 3, basically. The genius is in the game’s world-building, atmosphere, narrative design, and the fine crafting and layered thought that has gone into the vast majority of its core gameplay systems. The lack of stimulation comes by way of a great many bland, uninspired, slight, and inconsequential mission designs that frequently fail to make the most of what Mafia 3 is capable of.

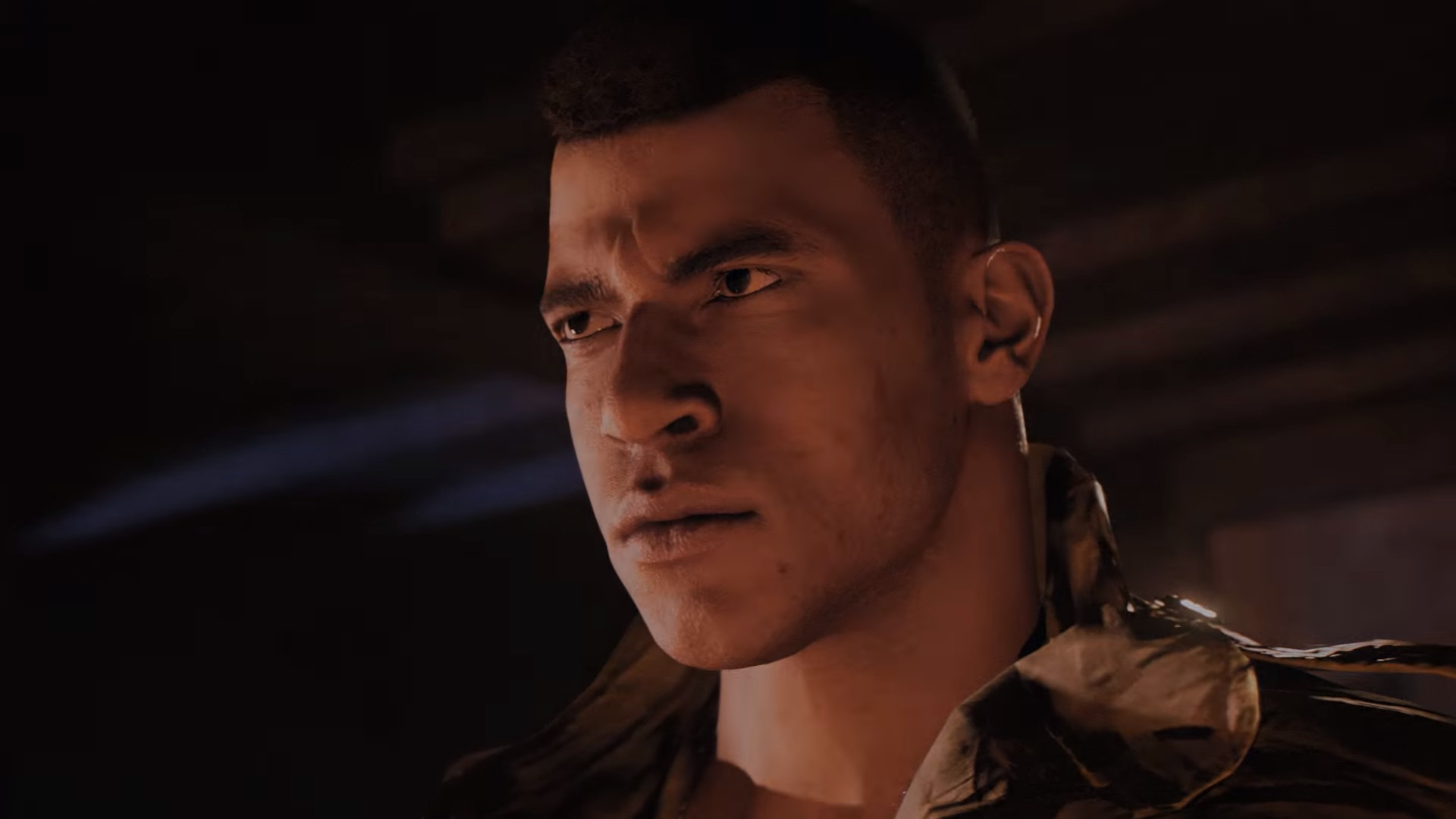

But let’s start with the good stuff. Because Mafia 3’s start is its purest distillation of the good stuff, and there’s a nice symmetry to that. Simply, Hangar 13’s game has the best opening four or five hours an open-world game has achieved in a very long time. Introducing its characters, themes, systems and structure by way of an intoxicating deep-dive into the socio-political melee of late-‘60s America, it starts in 1968 New Bordeaux – New Orleans in all but name – and follows returning Vietnam vet and Black Mafia member Lincoln Clay as he makes his first attempts to reintegrate into an environment deeply troubled on both a local and national level.

The hot, balmy southern air is thick with turmoil, as the war, civil rights, political ideologies, and multi-ethnic crime politics clash and shift. And Mafia 3 doesn’t sugar-coat any of it. Taking a bravely disjointed – but ultimately linear – structure during its opening hours, it jumps between time periods and perspectives whenever most effective to relate any specific angle of the story or present any particular point, using a disarmingly powerful, faux-historical documentary device to frame the action as a factual slice of the whole, anxious period. Fuelled by intelligent, sober writing, strong, sobering performances, and a mature restraint when it comes to sensationalism or judgement, it’s a matter-of-fact yet thoughtful intro whose intent is not just to present, but to discuss.

That this sequence plays as well as it is narratively conceived is the final, sparking touch-paper of Mafia 3’s initial, exciting potential. Along the way we’re progressively introduced to the game’s robust shooting, stealth, and driving systems, all of which handle with a satisfying, tactile heft. Gunplay is perhaps a little woolly when it comes to lining up finesse-shots under pressure, but pre-empt your kill by lining up from cover first, and you’ll find snappy, cartoonishly brutal headshots abound. And driving is just an endless delight, to the point that you’ll consistently find yourself hoping for long drives between objectives, just to experience the alchemy of car-feel and ambience that always infuses the experience.

Between the rich sense of time and place, the infectious atmosphere of Mafia 3’s many varied districts, and the pitch-perfect balance of arcade spectacle and satisfying control demands in the consummately well-honed driving model, simply being in and getting around New Bordeaux is perhaps the game’s pinnacle pleasure.

Main systems explained and naturalised, narrative beats and tone set up, we get the first taste of the game’s overall structure. Lincoln is fighting to take down the presiding Italian mob boss and wrestle control of the city for himself. To do so, he’ll hit each of the Italian mafia’s rackets in turn, reducing its income in a multitude of ways, with several options on the table at all times. Break into stash sites and destroy high-value resources, if you like. Kill or forcibly recruit key players in distribution and management. Strike a blow against the vice industry by carrying out hits on big-spending, but morally vile clients. You can pick any you like, and you won’t have to complete them all. Once you’ve done a certain amount of damage, you can move up the ranks and take on the local kingpin. This usually results in a big, stand-out, set-piece mission combining a gratifying amount of concept and craft.

But the problem? There’s a reason that these missions are such stand-outs. Once you’re past the introductory salvo and out into the open-world proper, a great deal of Mafia 3’s missions, objectives and activities really do not stand out at all.

Some of them are great, of course. And the aspiration of greatness is certainly there in the systems design. Objectives dotted around the city are always open to be tackled in any way you see fit, and Lincoln has more than enough capability to assist you in that goal. Between the omnipresent variety of possible entrances, cover placement suitable for stealth or all-out assault, a huge, ever-growing variety of weaponry and distraction equipment, and unlockable special abilities such as hired muscle hit-squads and the disabling of local phones to stop sentries calling for back-up, Lincoln is as close to Hitman’s Agent 47 as an open-world protagonist has perhaps come. Or he certainly would be if the actual tangible fabric of Mafia 3’s mission design consistently gave him the facility to use – or even need – these powers.

All too often, you’ll find these supposedly decisive strikes not in huge complexes or strung out over well-paced stretches of terrain, but hidden in small back-alleys, with only a handful of goons and a main objective to handle. Couple this with a very limited number of objective types – you’re almost always asked to kill a person, destroy a thing, or interrogate a lower-level enforcer, all of which effectively amount to the same process over varying degrees of scale – and the lengthy build-up to each major mission quite swiftly starts to feel like a thankless grind of anonymous busywork with intermittent highlights. All of these actions build toward an ultimate reward, but too few of them are rewarding to carry out in and of themselves.

In fact, that’s not the most fundamental problem. There’s also a very strange design decision amplifying the issue. On assassination missions, once you’ve killed the target, you’ve won. It doesn’t matter if you die immediately after, it doesn’t matter if you die in the process. Once the mark goes down, you’ve done it, and you will respawn with the task successfully ticked off. So why get clever during the multitude of smaller objectives? Why even bother planning out a strategy when you can just charge in, throw a few grenades, die almost instantly, and win anyway?

It all makes these inconsequential strikes feel even more meaningless, and worse, that eventually starts to erode the narrative and immersive integrity of Mafia 3’s wonderfully drawn world. And that’s just a damn tragedy. Because the maturity, detail, and resonant, grounded reality of that world is the game’s biggest, and most legitimately exciting, reason to play. It’s a truly special construction and, much as is the case with the well-crafted gameplay systems, it’s a real shame that the oft-underdeveloped objective design doesn’t serve it as well as it deserves. By the same note, long-term play begins to highlight weaknesses in the execution of otherwise great, over-arching ideas.

Witnesses to street crimes will often run to call the cops, theoretically leading to the moral dilemma of whether to take the hit or make it. But police response times are so slow that simply driving away will see you good 90% of the time. Bigger enemy enclaves will often put groups of goons in chokepoints, in an attempt to force quick, risk-vs-reward calculations of whether to remain hidden or go loud for a swift clear-out. But a quirk of the goon AI means that a simple whistle will often attract the human blockade, one by one, each oblivious to the from-cover stealth kill delivered to the previous until it’s entirely too late.

Throw in some intermittent but noticeable aesthetic bugs – nothing game-breaking, but the likes of subterranean car spawns, NPCs taking a Sunday drive with all the doors open, and instant meteorological changes certainly aren’t unknown – and you have a game of two very real halves. There’s the conceptual, artistic, and systemic side, which can rarely be faulted, and the concrete game that those elements wrap around, which too often lets them down.

But this yin-yang balance, by its nature, means that Mafia 3 is not a bad game, but rather a flawed work of huge potential whose overall quality is ultimately averaged out lower than it should be. The lows may be tiresome and drawn out, but the highs are very high indeed. Battling through an abandoned, flooded, voodoo-themed amusement park in the dead of night, opening plaza shoot-outs blending into a tense, (literal) ghost train of gloomy, stalk-and-kill cat-and-mouse. Anarchic, kinetic car chases, spiked with sparky dialogue, as three separate factions race and launch a parade of vehicles in a giddy bid to take each other down. Bonding with a new ally over an almost tower-defence style sniping mission littered with explosive barrels. A multi-floor hotel assault, with two ways in and two ways out, and highly contrasting carnage quotients flowing from each decision.

And the less directed, non-linear sub-missions are capable of greatness. Particularly in the second half of the game, larger fortifications, greater opposition, and more complex layouts certainly deliver some of the same verve, despite the persistence of much lesser activities in between. There’s an interesting parallel between Lincoln’s nuanced, very human journey of revenge and the process of actually playing Mafia 3. The story is full of thoughtful, morally and emotionally real characters who often question – directly or indirectly – why our anti-hero is doing what he’s doing. During Mafia 3’s weakest, most repetitive sequences, you’ll find yourself asking the same question.

But when the plan finally, inevitably comes together, when the big wins come and the heavy-hitters are conquered, and challenge and spectacle combine to invoke satisfying victory, all of the struggle will suddenly, if perhaps temporarily, be worth it. How willing you are to take that deal will depend entirely on how much work you’re happy to put in for the eventual reward. It’s all a matter of perspective, I suppose. But then, perspectives, and questions of sacrifice and fulfilment, are ultimately what Mafia 3 is all about.

More info

| Genre | "Shooter" |

| Description | Set in 1968 New Orleans, and capturing the vibe of that time and place perfectly, it follows the story of Lincoln Clay whos seeking revenge against the mob for the killing of his friends. |

| Platform | "PS4" |

| Alternative names | "Mafia 3" |