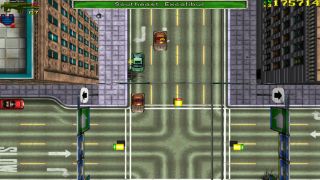

The making of Grand Theft Auto - From Race 'n' Chase to GTA

In celebration of Grand Theft Auto's 20th anniversary, this making-of series explores the turbulent origins of the multi-million dollar franchise.

Part Three - The road to success

While the original vision of Grand Theft Auto was scaled back for PC, the PlayStation version, although preserving the core of the game, lost even more features, including fire engines and trains. But 18 months into development, the entire city had to be razed and rebuilt, as programmer Brian Baird recalls.

"[Programmer] Mike Dailly came up with a new technique to draw 24-bit color tiles instead of the low-res ones we were using. Technically, it was stunning for its time but it required every single tile and graphic in the game to be redrawn. We borrowed most of the artists in the company to blitz the tiles for an ECTS demo to show off this new style."

If a new feature promised a better game, then it was included seemingly irrespective of the extra cost. The new artwork added another 12 months to the schedule. As Baird puts it: "There was always an overall plan with GTA. However, the day-to-day development was more flying by the seat of our pants."

Fortunately, publisher BMG was generally sympathetic, with a very hands-on approach from producer Gary Penn. Relations with BMG in the US, however, were not always as smooth.

As BMG took on more people from within the industry, some began to voice concerns, as publisher DMA's studio boss Dave Jones recalls: "We could not compete graphically with, say, Ridge Racer, so we were banking on the fact that the game was radical in terms of gameplay and its edgy content.

"The content side was never an issue. BMG supported us 100% to put whatever we wanted into the game; coming from the music business nothing fazed them. It was a real shame to see BMG lose its fresh approach and become more like a games publisher. BMG US didn't think you could release a top-down game into the market.

Red Dead Redemption 2 - release date, screenshots, and everything you need to know

"They said it would simply not sell and we should drop the title. This was only three months from completion. I was confident the sheer fun and originality factors would make it a success, and we also had great backing from BMG Europe. Luckily, we won the argument."

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Despite taking an entire year longer to produce than originally expected, Jones believes it was the right thing to do: "The extra time really benefited the game massively. We really pushed the boat out though on some areas such as audio, which I had not planned."

Fortunately, this resulted in another area in which the game took chances. "At that time most people's idea of good game audio was 'you didn't switch it off,'" recalls audio director Colin Anderson.

"I suggested that in order to add an interactive element to the music it might be nice to place them 'in the cars' as if they were coming out of the car stereo. That way, when a player got into a car the radio would start and when they got out it would stop: voila! Interactive audio. Once the idea of radio stations was established the rest was relatively obvious - DJs, news reports and different types of music for different types of car."

The radio stations also provided an added incentive to try the game's less powerful vehicles. With poor handling and low speed, the pickup would have been quickly abandoned if not for the guaranteed burst of spoof country and western.

Anderson's approach was unorthodox, and also controversial. "There were a sizeable number of people who felt it was too radical," he says. "I knew that was total nonsense because films do it successfully all the time. Different styles successfully blended because they work in context with the visuals."

A diverse range of tunes was also needed to make the radio convincing. "It wasn't good enough for the music to sound good enough for game music; people had to believe they were listening to real bands they just hadn't heard of," as Anderson puts it.

"They said it would simply not sell and we should drop the title."

Dave Jones

This proved very useful for DMA lyricist and PR head Brian Baglow - and was taken somewhat literally - when publicizing the game. "I let it be known that the bands and tracks were all real and licensed especially for the game," perhaps one of the more understandable exaggerations. Sadly not all the audio work could be used. The tank, for example, lost an interesting-sounding, if perhaps credibility-straining, version of the Star Spangled Banner.

With audio, graphics, the living city and the game's mission structure finally coming together, Grand Theft Auto was released to immediate success, justifying the enormous effort and compensating to some degree for the immense amount of lost work. Jones' determination, and BMG's indulgence, received their just rewards.

Unfortunately, having helped to create such a success, BMG pulled out of the games market shortly afterwards, much to Jones' regret: "It helped create one of the biggest games ever but didn't stay around long enough to enjoy it. BMG really would have been great for the industry."

GTA is often seen as inventing the sandbox genre, but in truth it built upon a strong heritage of arcade and freeform games. Even the game's trademark carjacking had been seen in Hunter and Mercenary before that. Its unique achievement was to take the best from what had gone before and fuse it together with ambition, skill and incredible attention to detail. That process was a complicated one, but the idea at the heart of GTA wasn't.

The word that comes up again and again when talking to its creators is 'fun.' If an opportunity arose to make the game more fun, no matter who it came from, and even if it meant throwing away a huge amount of work, it was seized with both hands. The series that resulted has been copied countless times, but few imitators have stopped to think that the secret to its success may lie in the process, not the product.

Want more GTA? Then check out our GTA 5 guide and GTA 5 cheats: everything you need for PS4, Xbox One and PC.

Edge magazine was launched in 1993 with a mission to dig deep into the inner workings of the international videogame industry, quickly building a reputation for next-level analysis, features, interviews and reviews that holds fast nearly 30 years on.