The making of Resident Evil 4: "By that point in the series, zombies were simply no longer scary to players"

Capcom producer Hiroyuki Kobayashi looks back on how this genre defining monster was made

Oddly, the best thing about Resident Evil 4 is that it isn't really a Resident Evil game. With the established survival horror formula perfected by three PlayStation games and several spin-offs, both the development team and fans wanted something new, something different, something challenging.

This didn't come easily for Capcom, with the team exploring supernatural elements and the paranormal in early development as workarounds to the growing zombie fatigue, but it's hard to argue that the final product wasn't worth the wait. Eschewing static camera angles for an over-the-shoulder affair that quickly became the staple for third-person shooters and leaving the brain-munching idiots to rot in order to let a parasite-ridden populous take centre stage, this was no longer survival horror – it was survival terror.

It's a subtle difference in terms of language, sure, but it's an important distinction to make. Resident Evil's foundations were in classic B-movies and horror films – static cameras allowed for staged scares and classic cinematography techniques, the action contained and controlled by the director at all times.

While elements of horror and certain tropes remained in Resident Evil 4, they were no longer the be-all and end-all and the fear of stumbling into a small army of villagers armed with rudimentary tools or just one obvious threat (the likes of mini-bosses Dr Salvatore and El Gigante reminiscent of stalking threats Mr X and Nemesis in previous games) without the provisions or skills to see the task through proved genuinely terrifying. Horror is a jump scare around the next corner when the cameraman decides to reveal it; terror is finding yourself out of your depth only to hear the ominous revving of a chainsaw nearby. See? There's a difference, alright...

Into the unknown

If you want more in-depth features on classic video games delivered to your door or digital device, you should click the link and subscribe to Retro Gamer.

"Our focus was on creating something completely new with Resident Evil 4 and pushing the series in a new direction," explains producer Hiroyuki Kobayashi. "In the course of development, we created prototypes and tested them out – if we weren't satisfied with them, we started from scratch. In the end, we went through four different versions of the game before settling on the direction in which we wanted to go."

Psychological horror was then still very much Silent Hill's domain, while the paranormal stuff Capcom tried sort of went against the grain of a series grounded in its own hokey science with various strains of virus, yet trying typical zombies only made the game feel stale and familiar. "By that point in the series, zombies were simply no longer scary to players," Kobayashi confirms. "They had become cannon fodder that you could defeat with ease. We wanted something not like the enemies you'd seen before that would bring back the sense of the unfamiliar and the frightening, and that was the genesis of Los Ganados."

The parasite-based nature of these new definitely-not-zombie enemies was the light bulb moment Capcom had been waiting for. As well as granting full creative freedom to go nuts with new and inventive enemy types – from mutated bugs that had been exposed to the parasite to once-human hosts with an aptitude for (or lack thereof) these powerful parasitic friends – it also managed to tie into the existing lore as a new line of biological weapon experiments, ticking every box while still scrubbing the slate clean for a whole new roster of horrible foes and challenges to overcome.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

The shift of premise was necessary in order to avoid burning fans out on zombies, but the switch to more action-centric gameplay was a little less expected. "We took a look at games that were popular in the western market at the time, around 2005, and it was clear to us that games which let you aim and shoot with precision in that third-person style were the way to go," reveals Kobayashi.

"Getting the position of the camera behind the player just right was a very arduous process of refinement"

Hiroyuki Kobayashi, producer

Many thought this shooter pandering was the downfall of the ill-received Resident Evil 5, but it turns out the wheels were already in motion to develop greater interest in the western market a full decade ago. Granted, later sequels have had a tendency to stride boldly into full-on shooter territory where Resi 4 merely had a bit of a paddle (be careful of Del Lago, guys...) but still, if you want to point fingers and name a culprit for the recent action bent, you'll only find yourself prosecuting one of the greatest games ever made.

It's all too easy to take great game design for granted, and even from the various pre-release builds of the game, you can really get a feel for just how many different camera placements the team must have gone through before settling on the version that shipped. Beta footage shows a hybrid of fixed and aim-based cameras, while you can see various heights, depths and angles that all offer different takes on the action in that early footage.

"Getting the position of the camera behind the player just right was a very arduous process of refinement," Kobayashi admits. "It's just one part of the game but you really need to nail it as it influences every other aspect of the gameplay." Ever since, we've played countless third-person games where the camera just feels 'off' in a way that's hard to describe – too floaty, perhaps, just slightly too far away or maybe too stiffly attached to the player character – which just adds more weight to the argument that Resi 4 did this better than pretty much all games that had come before and indeed many since. Way to go, Capcom.

A difficult balance

"We went through four different versions of the game before settling on the direction in which we wanted to go."

Hiroyuki Kobayashi, producer

There were other challenges ahead of the team due to the quicker pace of the game, too. Players would quickly grow used to enjoying huge-scale encounters (either in terms of enemy numbers or sheer size) and where the tension of the original games allowed for minimal enemy placement for maximum effect (thus slowing the rate at which players could adapt to each enemy), having them appear in bigger groups and more frequently meant that something had to be done to avoid having people feel they had mastered a new enemy type in a matter of minutes.

When pressed for the greatest design challenge during development of this game, in fact, Kobayashi cites this exact issue as the main hurdle in the game's development. "Probably the process of working out what kind of creatures should show up in the second half of the game," he confirms. "By that point, you've become more accustomed to Ganados so keeping things interesting while remaining true to the atmosphere of the game is a difficult balance."

Capcom clearly had its fair share of challenges in steering the franchise in this bold new direction, so it's interesting how the team decided to pass these onto the player. One such example of this is the inventory system – gone is the simplistic small grid where every item, regardless of bulk or weight, takes up one slot, replaced by a much larger grid in the form of the upgradeable attache case, where item size determines how many 'blocks' it takes up.

The existing system for micromanaging your inventory had become stale and overly simple by this point (just take an Ink Ribbon, a healing item, your primary weapon and some reserve ammo, leaving room for ferrying puzzle items around) but this ingenious new mechanic made us think about what we were carrying and why, becoming almost a mini-game in its own right. "Funnily enough, Tetris was the inspiration," Kobayashi laughs. "I thought it would be fun if you had to play a puzzle game where you tried to fit the pieces in together as best you could without any gaps to maximise efficiency."

Memorable encounters

Resident Evil 4 in VR is the most fun I've ever had with a Resi game.

While it might be one of the all-time greats, however, Resident Evil 4 still has a lot to answer for. Its use of Quick Time Events (QTEs) – which Capcom managed to employ to great effect – became something of a touchstone for other developers looking for an easy way to incorporate cinematic events into their games without fully wresting control away from the player, but few managed to pull them off nearly as well. Their proliferation across games of all kinds quickly made many players come to hate them, although Capcom's execution of them was generally masterful – just as jump scares could once hide around any corner, QTEs instead tied into the new emphasis on terror. Mashing buttons to run away from a collapsing pillar, for instance, wouldn't have been nearly so intense if all you had to do was just hold down on the analog stick for a bit, and never knowing when that prompt would appear left you clinging to your controller at all times, just in case.

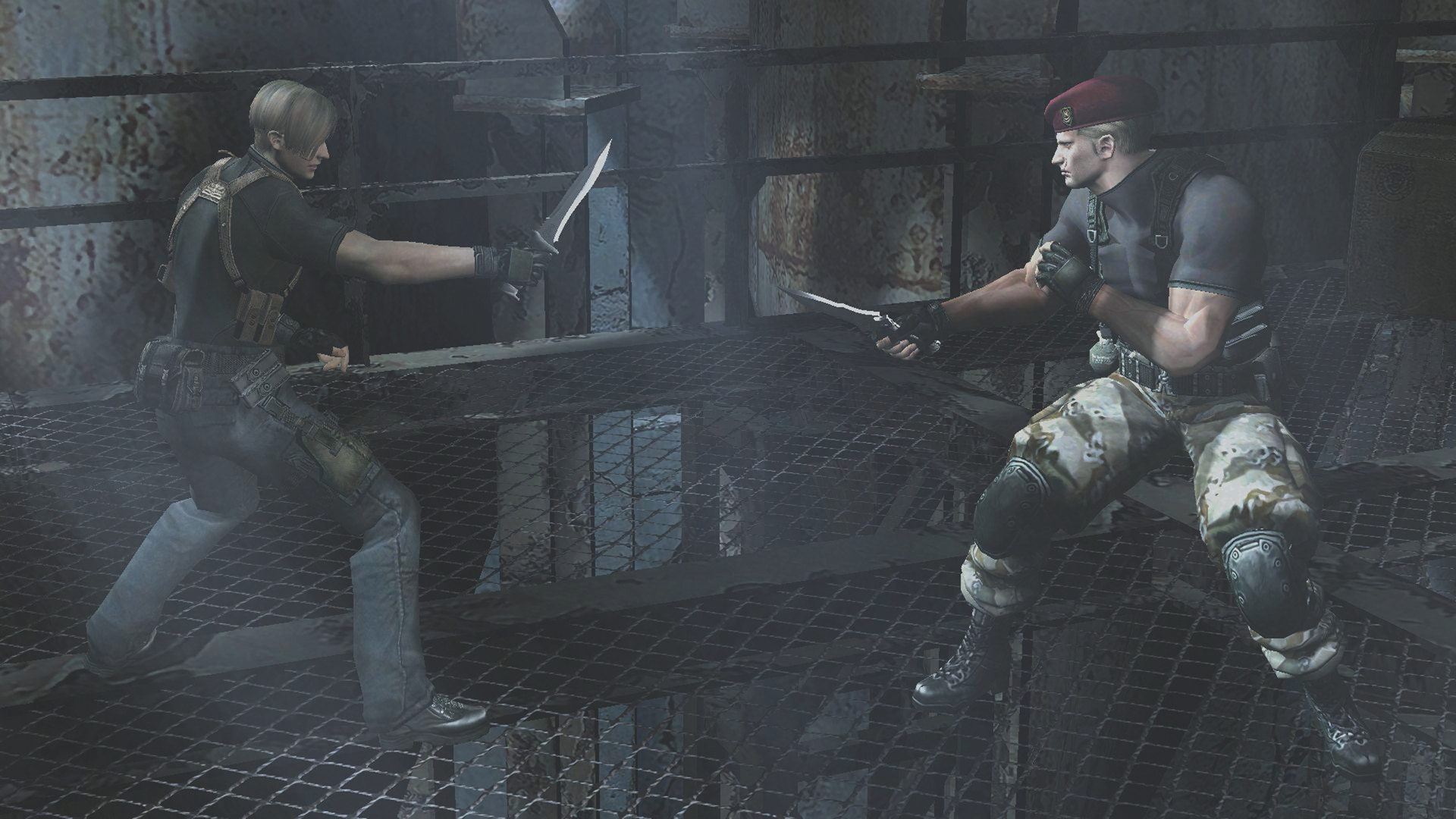

QTEs also formed the backbone of one of the game's most memorable encounters – the knife fight with Krauser towards the end relied heavily on prompted inputs (and is Kobayashi's favourite battle in the game – "I really like the boss fight against Jack Krauser. His knife moves were so cool!" he enthuses), allowing the battle to build way more tension than it could have managed within the confines of traditional control.

That's the reason games like those made by Quantic Dream continue to employ such mechanics so heavily, as it leaves players free to focus on action and narrative until such a time as they are called upon to take action. They're also used to decent effect in Telltale's twist on the classic point-and-click formula with games like The Walking Dead, showcasing how Resi 4's masterclass in QTE use continues to permeate the market and evolve today.

Kobayashi seems delighted that his game is still so revered 16 years later. "It's an incredible honour that makes me very happy indeed," he tells us. "It's been [over] 10 years since the game came out, and it's great to see how much the fans have loved the game in that time."

This feature first appeared in issue 150 of Retro Gamer magazine. For more excellent in-depth features, you can pick up print and digital versions of the latest issue from Magazinesdirect.

Retro Gamer is the world's biggest - and longest-running - magazine dedicated to classic games, from ZX Spectrum, to NES and PlayStation. Relaunched in 2005, Retro Gamer has become respected within the industry as the authoritative word on classic gaming, thanks to its passionate and knowledgeable writers, with in-depth interviews of numerous acclaimed veterans, including Shigeru Miyamoto, Yu Suzuki, Peter Molyneux and Trip Hawkins.