The making of Super Metroid: Looking back at the origins of an all-time classic

With Metroid Dread bringing Samus back, Retro Gamer explores the making of one of series' most memorable entries

Heading back up to ground level as I leave the immaculate subway at Jujo Station in the south of Kyoto, I walk through this remarkably unremarkable suburb until I see the big white block that houses Nintendo's contemporary headquarters. The gates to NCL are manned by two portly, middle-aged guards who seem to project a faintly threatening presence, which is comically undone as I notice, behind them, in the back of their little booth, a stash of NCL-manufactured toy guns apparently left over from the Seventies and a selection of Nintendo character plushes from the Famicom era. This may not be the original Nintendo HQ site, but it clearly retains the company's history like a hoarding retro gamer hangs on to loose carts.

Inside, beyond the pristine lawns and shiny entrance, I enter a marble- floored, austere world whose foyer is staffed by painfully polite and correctly spoken Nintendo officials. Eventually I'm led into a meeting room on the ground floor, where I sip the o-cha kindly provided by the demure NCL woman as I wait – and slightly nervously revise my notes and cue my Dictaphone – until a smiling, ponytailed artist type arrives and immediately makes his introduction. This is Yoshio Sakamoto, producer of Super Metroid back in the early Nineties and still an integral Nintendo developer today. "Hajimemashite. Yoroshiku onegai shimasu."

Sakamoto has brought with him a small booklet containing an overview of Super Metroid to aid his memory – the game was completed 15 years ago, but the Metroid legacy stretches back two decades – as we chat.

Super Famicom

If you want more in-depth features on classic video games delivered straight to your door or digital device, you can subscribe to Retro Gamer here.

"To start with, there was the Famicom Metroid game," he recalls. Sakamoto worked on that first Metroid adventure, and its relevance to Super Metroid is particularly important because of the unchanging core concept of the 2D Metroid games; a core that was formed in said Famicom Disk System original of 1986.

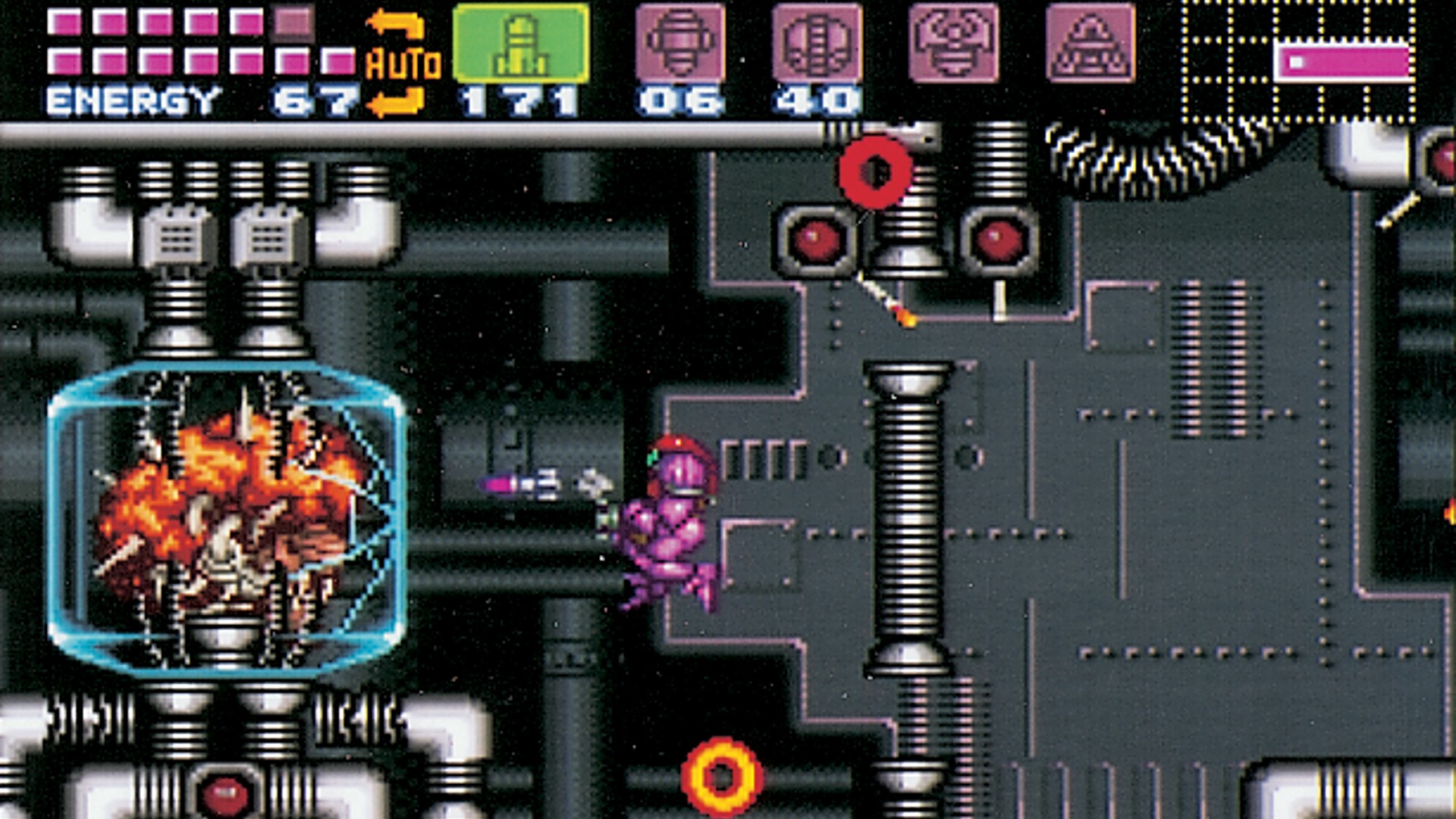

"My boss [producer Makoto Kanoh] told me that Metroid was really popular in North America, so he encouraged me to produce a new Metroid game with the high-quality graphics that were becoming possible thanks to the Super Famicom. Of course I said, 'Yes, I'd like to try doing that.' The game design and concept had already been established before Metroid II was produced for the Game Boy," Sakamoto explains. "When it came to making another sequel, this time for the Super Famicom, we really wanted to see how far we could push the SFC to generate greater power of expression and enhance the appearance of the game world, all while working with a basically unchanged concept. That was our initial motivation as far as Super Metroid was concerned: to build on the expressiveness of Metroid II and achieve greater presence, something closer to a reality."

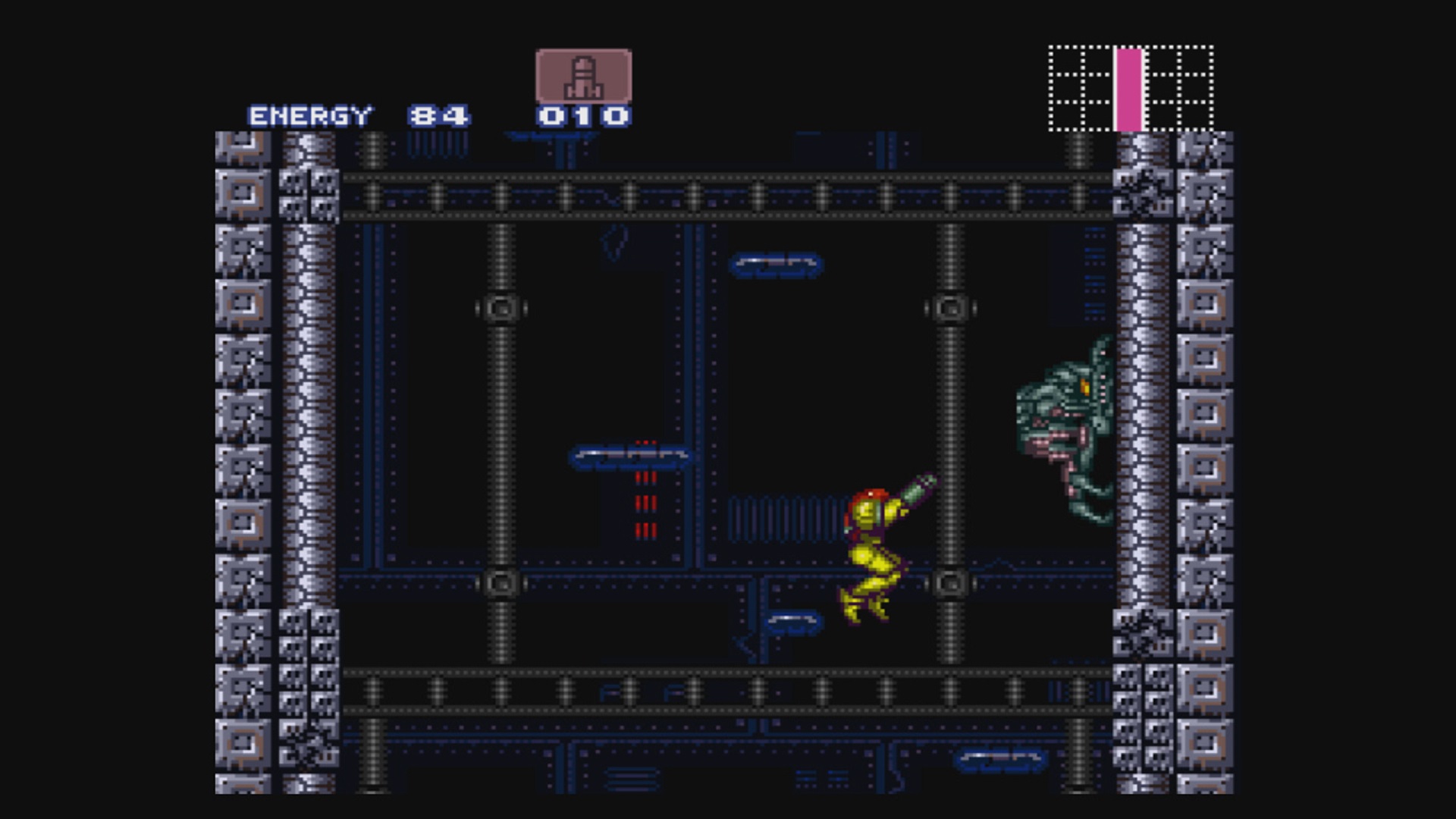

Sakamoto had nothing to do with the development of Metroid II – at the time his services were required elsewhere within NCL – yet that sophomore title in part shaped the plan for Super Metroid: "As the last scene depicted Baby Metroid being born right in front of Samus's eyes... well... there's no real explanation for that in the course of the games, but that scene was another source of incentive for us in that we wanted to follow on from that ending, linking Metroid II with Super Metroid. We were determined to keep the same world-view and maintain the continuity of the story."

Aside from the basic formula of play that was set in motion by Metroid, the code on that million-selling disk also plotted the aesthetic direction of the series. I suggest to Sakamoto-san that Super Metroid and the Metroid games in general don't look like 'typical' NCL games and I ask him why that might be. He sips his tea and then replies: "I think the film Alien had a huge influence on the production of the first Metroid game. All of the team members were affected by HR Giger's design work, and I think they were aware that such designs would be a good match for the Metroid world we had already put in place. To be honest, I've never really been clear on what is or isn't the 'Nintendo look', but as far as we were concerned, we were just projecting another image from within Nintendo – another face of Nintendo, if you like. But yes, it's a science- fiction game, so..."

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Other than the artistic influence of Necronom, Sakamoto reckons that numerous games affected the style of Super Metroid – "I can't list them... There are just too many of them" – although he counters this by highlighting the experimental side of his team's early work: "For the prototype stage of Super Metroid's development we just had a few Intelligent Systems programming staff, myself, and another [in-house] Nintendo designer. We examined what was possible in the game, and as the core Metroid system was already in place we considered how we could make the game easier to play, what new ideas we could incorporate, and so on... Then we drafted in lots of other NCL and IntSys developers once we got beyond that stage and into the proper work."

IntSys

There has always been a complex yet mutually beneficial relationship between Nintendo, then based in Higashiyama (to the northeast of the current Minami location), and Intelligent Systems, constantly situated in the eastern Kyoto ward of Higashiyama. Sakamoto refers to the team as "IntSys" and says that it had been helping Nintendo with the Metroid series since the initial FDS game, "as a second-party developer". While it's fair to say that the game design and play-testing abilities of NCL's in-house staff have always been some of the world's best, Intelligent Systems' developers were on hand to provide indispensable technical know-how, particularly focused on the hardware side of things.

"IntSys has always been very capable with hardware," Sakamoto adds, "so during the experimental stage we told the IntSys programmers what kinds of things we wanted to do and verified what in reality could be done. We'd been well prepared for the move to the Super Famicom hardware, so we had some idea of what to expect before we went into it; which features we should use, and how. I think it was good that we went through the prototype stage because it gave us a base onto which the post- experimental stage staffers could easily begin their work. At the time, the SFC was reputed to be difficult to develop for.

Depending on how you partitioned the Super Famicom's video RAM, which looked after the sorting of image information, the scope of possibilities would change wildly. Knowing that you could diminish the VRAM's potential by poor partitioning was useful information, because it meant we could think about how certain things could or couldn't be achieved, and how we could work around those limitations. As we were migrating from the Famicom to Super Famicom, really everyone – not just Nintendo but other developers too – seemed to be having fun testing the feature set of the new hardware. That went for us, too: I remember often thinking, 'Oh, I had no idea we could even do this!' The graphics and sound were fantastic, but we were still driven by wanting to [not] be outdone by the arcade games of the time."

To a man, the developers supplied by IntSys to work on Super Metroid were all programmers. In spite of the various backgrounds of the Super Metroid team, there was apparently no NCL-IntSys rivalry; no factions, just harmony and productive co-operation. Key team members from the Nintendo side included Makoto Kanoh, the producer, the guy who instigated the project; my interviewee, Yoshio Sakamoto, who was the director in charge of game design; and Tomomi Yamane, who was the figure Sakamoto regards as having been the 'main' designer: "He was very skilled and was particularly interested in the hardware stuff, consulting with the IntSys people as to what kind of images could be displayed."

"We wanted players to explore everything we'd made and then move on. That's why we designed the maps in such a way that the player couldn't escape without exploration, or such a way that the player would end up back at a starting point before advancing."

Yoshio Sakamoto

Even though the team's objective was to build on the success of Metroid and Metroid II, only three of the original Metroid team, including Sakamoto himself, worked on Super Metroid: "The rest of the [NCL side] was made up of young trainee developers," he recalls. "Of course young people can be quite impertinent – and those on the Super Metroid team certainly were – but I think that's quite important in a way. These young people had enough about them to help us a lot. There were many different personalities in the Super Metroid team, which was a good thing. It was a harsh development environment, so I'm sure that some of the staff didn't enjoy the work, but generally the team was full of the 'Let's go for it!' spirit. I think that was partly because of the timing as well, what with the Super Famicom pushing everything to the next level."

The "next level" wasn't merely the notion of advanced graphics and sound: it was also a matter of the expansion and improvement of level design. However, Sakamoto and team were reluctant to drag Super Metroid into the realm of storytelling methods utilised by RPGs and other adventure games.

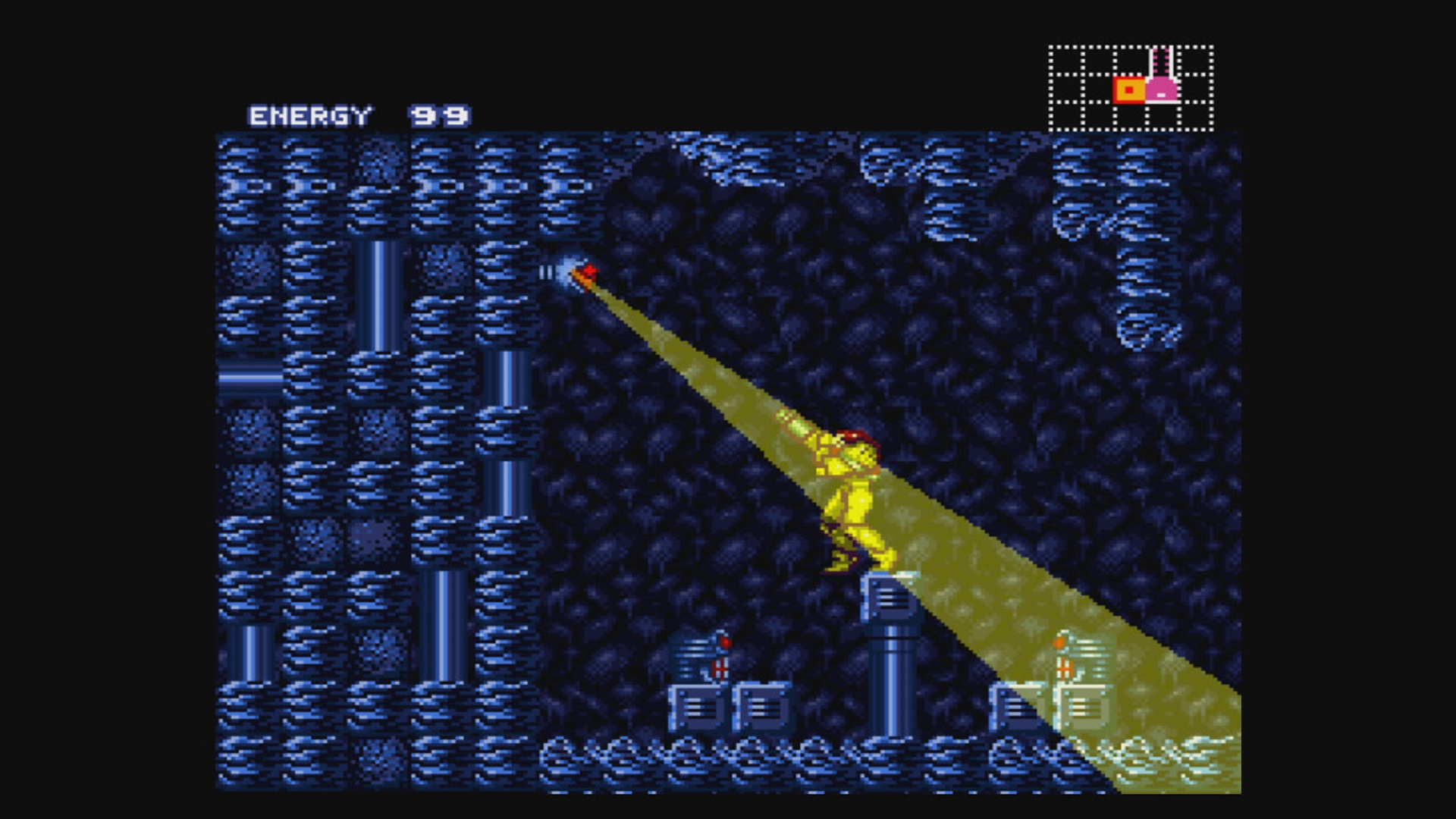

"We really didn't want to explain things to the player using too many words," Sakamoto states. "We just wanted to let them play and be able to work things out for themselves. For example, say there's a mechanism where you need to climb up a ladder and place a bomb there in order to advance, as one component in the solution of a [gameplay] riddle; if that was all you needed to do in order to get through to the next area, you'd miss all the other mechanisms we'd put in place and wouldn't even realise that certain parts of the game existed.

We wanted players to explore everything we'd made and then move on. That's why we designed the maps in such a way that the player couldn't escape without exploration, or such a way that the player would end up back at a starting point before advancing. The player would be cornered/driven and would eventually be forced to stop and say, 'Right, how should I think about this area?' That's the essential point of Super Metroid's map design. Not using words meant that the player had to feel his/her way through the game – and that's how we wanted it to be. When they discovered something new – a new item or new location – we wanted the player to feel that he/she had made that discovery independently, without help from the game."

Finding balance

Look back on series with our ranking of the best Metroid Games.

R&D1 went to great pains to achieve the fine balance seen in Super Metroid's item locations, puzzles, boss encounters, and in Samus's acquired abilities and inventory use. It wasn't simply the case that everything fell into position at the first attempt at design either, as Sakamoto reveals:

"In a stage following on from an area where the player made lots of discoveries, we'd hold back from pushing the player too far in order to avoid repetition. Balance between difficulty levels and player discoveries was crucial. We wanted to avoid creating an on-rails experience – we wanted the player to feel free. But it was incredibly difficult to get that balancing act right. We'd been designing levels in this way since the first game, so we had a lot of experience but we still needed to experiment and build and rebuild."

As well as being a Metroid debut for most of the team, Super Metroid marked the Super Famicom debut for all concerned. Naturally, this step up presented some hurdles that even the advice of IntSys couldn't equip the team to surmount. "One problem with the shift to the Super Famicom," Sakamoto says, "was that it meant we suddenly needed a lot more sprites and artwork, so we shared the map and enemy design responsibilities throughout the team, with everyone making some input in those areas. But then doing that resulted in a complete mishmash of styles because of each designer's individual preference, so in the end I had to ask Yamane to retouch everything that had been submitted, bringing it all together as one consistent design."

Remarkably, there was no friction within the team even during the frenzied last stage of development, although there was something of a bad smell: "During the final six months of development I didn't know where I lived any more; the Nintendo building – not here, but the old place [in Higashiyama] – became like a boarding house for the Super Metroid team," Sakamoto grins. "It got to the stage where I really don't remember going home at all! There was a nap room where it was okay to sleep, but sometimes it was full [of sleeping, overworked Super Metroid staff] – those were the worst times, when I wanted to sleep but couldn't, and I didn't have time to go home!

There were always between ten and fifteen of us in the office through the night, so we had to take naps in turns. The nap room wasn't being cleaned or looked after at all, because we were always using it; one morning staff from another area came to wake us up and told us that the room smelled like a zoo. Another Nintendo employee put a room freshener in the nap room, but that only made the place pong even worse. Everyone in Nintendo gave us funny looks," Sakamoto laughs. "It's quite sad having only these kinds of memories!"

Our talk soon takes a turn from development room stench to the wrath of a Nintendo demigod: Gunpei Yokoi. In his early 50s at the time of Super Metroid's production, Yokoi was the game's general project manager but did not exercise any hands-on control. Sakamoto remembers how his superior viewed Super Metroid:

"Yokoi-san, who at the time was my section chief and who always had fresh ideas, was always angry when he saw us all completely absorbed and working crazy overtime on Super Metroid. He came in and said, 'Are you lot trying to produce a work of art or something?' [Laughs] But this was an epic and we were already way past our deadline, and it seemed we were getting progressively further from our objectives – Yokoi-san was becoming angrier with us day by day during that period.

We weren't aware of it, but Kanoh was given a warning by Yokoi-san. Although he was really unhappy with us, and even though he wasn't the type to dish out praise, Yokoi-san was constantly playing Super Metroid once we'd finished it – he was hooked. He was playing it so much that I wondered what he was up to. [Laughs] When other developers brought their action games to Nintendo, he'd always compare them with Super Metroid and invariably ended up recommending the third-party developer to 'go away and play Super Metroid'. That's how fond he was of our game. I suppose this is a better memory than the smelly nap room anecdote," Sakamoto laughs.

"Super Metroid was released in '94," he continues, "and development had taken us between two and three years. I don't know how it was perceived throughout the company, but the timing was such that all teams were focused on putting out lots of new SFC games, so there was obviously some expectation that we deliver with Super Metroid. We definitely had a lot of support and understanding of the game's concept from people related with the project, and that helped to ensure that we did a good job." Which, as everyone who has played the game will quickly attest, is a monumental understatement. And if it was good enough for Gunpei Yokoi, it's certainly good enough for us.

This feature first appeared in Retro Gamer magazine. For more excellent in-depth features, you can pick up print and digital versions of the latest issue from Magazinesdirect.

Retro Gamer is the world's biggest - and longest-running - magazine dedicated to classic games, from ZX Spectrum, to NES and PlayStation. Relaunched in 2005, Retro Gamer has become respected within the industry as the authoritative word on classic gaming, thanks to its passionate and knowledgeable writers, with in-depth interviews of numerous acclaimed veterans, including Shigeru Miyamoto, Yu Suzuki, Peter Molyneux and Trip Hawkins.