The making of Warcraft: Orcs & Humans – the groundbreaking strategy game that paved the way for World of Warcraft

World of Warcraft Classic is a heavy dose of nostalgia, but before it there was another

Mention the name Warcraft today and most people will immediately think of World of Warcraft, the incredibly successful MMORPG that has dominated the genre since 2004 and has recently been re-released as World of Warcraft Classic. Yet the story of Warcraft began over ten years earlier with an embryonic company named Silicon and Synapse, who would soon transform into the more commonly-known Blizzard Entertainment. The company's founders were Allen Adham and Michael Morhaime. "I knew Mike from an engineering fraternity at UCLA," begins Patrick, "and he invited me down to offer me a contract role converting the DOS/Amiga game Battle Chess to Windows 3." Patrick worked on this conversion from February until June 1991 before graduating from university and beginning full-time employment at Silicon and Synapse later that year. Patrick was soon busy on various SNES projects such as The Lost Vikings and Rock 'n' Roll Racing. However, despite good critical reception, they weren't big sellers, resulting in a focus on PC products.

"One day in September 1993, Allen came up to me and told me to take over a new project called Warcraft as producer and programming lead," recalls Patrick and there was little doubt of the main source of inspiration for the game. Many of the Silicon team had become addicted to the iconic Westwood game, Dune 2, discussing almost every day the various tactics and styles that could be used. "It wasn't so much a gap in the market, as an opportunity," he smiles, "as it was obvious to us that Dune 2, despite our fondness for it, had weaknesses. We thought we could create something special if we improved upon the design." The first major change was the setting – "We all loved fantasy and Tolkien was a major inspiration" – and Patrick also confirms that a Warhammer licence was considered. "It was certainly discussed. Allen was keen on it to try and increase sales and gain brand recognition but as far as I was concerned, I was pleased when nothing came of it. We wanted to create and control our own universe, although Warhammer became a big influence in the art style of Warcraft."

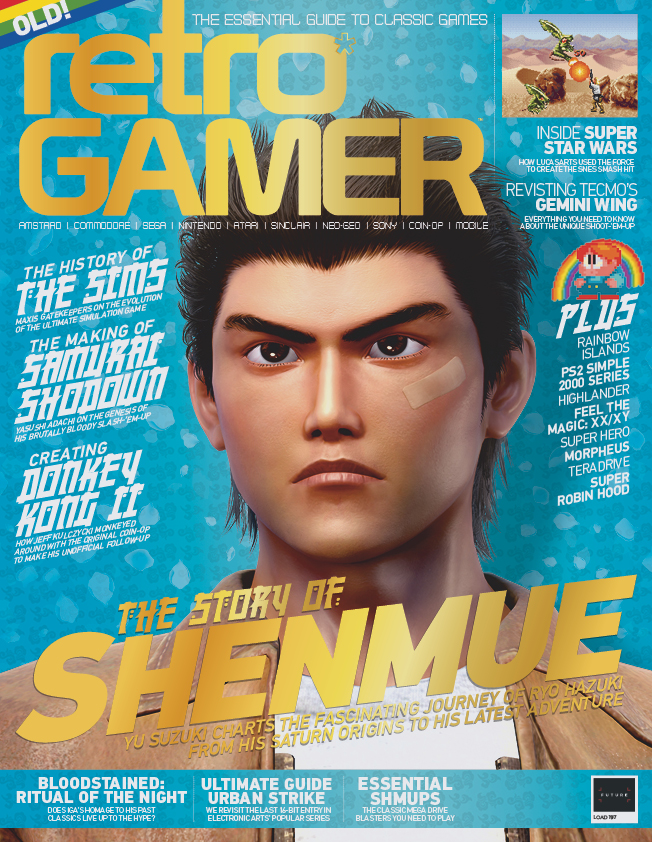

This feature first appeared in Retro Gamer magazine. If you want in-depth features on classic video games delivered straight to your doorstop (or your inbox), then you really should subscribe to Retro Gamer.

Patrick and the team began to tweak the design of Warcraft with changes borne of their extensive play-testing of Dune 2. In came two-player LAN and Modem play, multiple-unit selection and upgradeable resources. As a result, one of Dune 2's most controversial elements that ultimately remained in Warcraft was the controlled town expansion – construction could only take place next to roads laid by the player – which was chiefly implemented to avoid the player constructing "stealth" towns next to an opponent's base. "I think in retrospect that was a bad decision. We argued about it a lot at the time and it stayed in; but it was one of the first things we eliminated when it came to Warcraft 2."

"The process of creating Warcraft was very organic," continues Patrick, "and to start off with was mostly me writing code as fast as I could for several months." When the game began to form, Blizzard brought in Ron Millar to head up the design, a small team of programmers to assist Patrick with coding and graphics and the storyline was devised. However, a divergence in the direction of the gameplay was soon appearing; Warcraft was turning into something quite different from the series we know and love today.

A focus on simplicity

"Initially Ron led the design away from Dune 2 and towards games such as Populous. For example, peasants weren't going to be "built", but would instead pop out of farms after a while. It didn't feel right to many of us," says Patrick. This type of unit creation limited the player's control; each peasant could be converted into another unit, yet there was no direct influence over quantity or timing. The gameplay was planned but never implemented and this was mainly down to graphics artist and designer Stu Rose, as Patrick explains. "While Allen and Ron were off at CES in Chicago, Stu made some proposals about how the game should work, essentially making it simpler to play and closer to Dune 2 again." The remaining team discussed the ideas and agreed they would make for a much better playing experience. Patrick implemented the changes as quickly as possible to present to Adham and Millar on their return. When they saw what had become of Warcraft, they reluctantly agreed the alterations were for the best – much to the team's relief.

Patrick confirms one of Warcraft's principal design tenets: simplicity. "Many games were just too hard to play because they required detailed interaction with the user interface," he explains, "so our goal was always to create a game where the interface just got out of the way of the gameplay." One of the elements the team quickly learned during development was the use of hot-keys; it was evident that in a real-time battle, players needed to give actions to their units commands quickly and easily, given the unit control limit.

It seems odd looking back today that you can only select up to four units at once in Warcraft, yet this method sidesteps one of the criticisms of Westwood's Command And Conquer series where no such restriction existed. "Allen Adham was the chief proponent of the four-unit selection limit," reveals Patrick, "and whilst we didn't all see eye to eye on it, we realised it had merits." The limit served several purposes, most importantly making the game more tactical by eliminating "tank-rush" tactics and forcing the player to concentrate more on the meat and bones of the game: combat.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

"If you had played Warcraft back in 1993, you'd have been able to drag-select as many units as you like," discloses Patrick, "and although it was a really useful way to determine my path-finding and unit formation code – select fifty units and tell them all to go to the other side of the map and watch the unfolding chaos of a traffic jam – I thought the limit was the correct decision at the time." Whilst Patrick's subsequent code tinkering and the four-unit selection solved the traffic jam issues, he concedes in retrospect that perhaps four units was too low; the limit was raised to nine for Warcraft 2.

Technical challenges

It wasn't just the design that caused the development of Warcraft to stumble; there were several technical issues too. "We were very keen on multiplayer play and our biggest challenge was debugging the multiplayer sync errors," frowns Patrick. These bugs occurred when the data between each game did not correspond correctly, usually resulting in the game crashing. "The very first multiplayer game was between myself and fellow coder Bob Fitch. It was a bittersweet moment: playing that first game was the most brilliant experience, because it was the game I was writing and I knew there was another tactically adept player controlling the other side." Unfortunately Patrick's joy was short-lived; a "desync" soon struck followed by an abrupt crash leading them to realise that creating a smooth multiplayer Warcraft experience was going to be much tougher than they had originally envisioned.

"We discovered many sync bugs, and at one point it was so bad that Allen said we had to drop multiplayer, release a single player game and then add the multiplayer later." Still passionate about its inclusion, the team fought for it to be re-instated and Patrick still firmly believes that if multiplayer had been dropped from the original Warcraft, Blizzard would not be the company it is today. "There was a period of several months where I tracked one specific bug. The game was so close to shipping without multiplayer but we got it in the end and shipped just two weeks late." he remembers. Other issues were slowly ironed out and relatively minor compared to the dreaded sync bugs.

By this stage, Warcraft already boasted its distinctive bright and cheerful graphics that belied the frequent bloody battles. "There were lots of companies that were going for the gritty look in their games, but I think our artists' experience with making characters "read well" for the early console games we developed really had a big impact here. Sam Didier led the art and had a style that was so engaging, everyone who saw it loved it," explains Patrick. Blizzard's artists worked under a policy that all artwork had to be drawn under fluorescent lights rather than dark rooms, with the theory being that as it was the worst possible light, the artwork would look better in any other light.

Bright and colourful

Consequently, Warcraft's artwork and graphics had to be bright and colourful to stand out against these harsh conditions and the game's humour went hand-in-hand with this style says Patrick. "We tried to use humour effectively in all our games, because it's another aspect of entertainment. We felt too many games took themselves too seriously whilst we just wanted to entertain people."

Towards the end of the development of Warcraft, an important member was added to the team. Bill Roper joined ostensibly to back-fill the Orcs versus humans storyline and ultimately lent his charismatic talents to one of the most memorable features of the game. "Along with guys who laid down the foundation with the artwork, Bill did a fantastic job creating the voice-tracks to Warcraft," says Patrick proudly, "and the many humorous one-liners that gave the game its personality." With Bill also helping to design the game's manual, Warcraft was beginning to take shape very nicely with Patrick and the team still seemingly unaware of a notable rival that was also being developed at the same time. "It wasn't until we met up with the Westwood folks at trade shows after the release of Warcraft that we began to learn what it'd been up to with its follow up to Dune 2 – Command And Conquer. My impression was they weren't exactly happy over it; but I reckoned they should have been pleased that we'd taken their great game as a base for ours."

On release, Warcraft was a big success and a sleeper hit. Did this surprise Blizzard? "Well, yes and no," says Patrick, "We knew it would be successful because, hell, it was addictive! When we shipped the gold master discs, everyone just kept playing the game and no-one would go home! But our idea of success was selling 200k units, so I guess we were surprised, as although the game didn't take off straight away, it was a consistent seller; word of mouth meant we sold 400,000 units in around a year – which we thought was awesome."

We conclude by asking Patrick how he sees Warcraft's significance today. "Blizzard is the company it is today because of the things we did all the way back in 1992. We made mistakes, but learned from them. We argued a lot internally, but came up with the best solutions to hard problems. And from those beginnings we built a company where we knew all the right answers, answers that were right for the players which led to the vast popularity of our games in later years. And Warcraft was there, practically from the start."

This feature first appeared in Retro Gamer magazine issue 111. For more excellent features, like the one you've just read, don't forget to subscribe to the print or digital edition at MyFavouriteMagazines.

Graeme Mason is a freelance writer with an expertise in all things retro gaming. Alongside his bylines at GamesRadar, Graeme has also shared his knowledge and insight with Future's Retro Gamer and Edge magazines, as well as other publications like The Guardian and Eurogamer.