"Mature" games that are actually mature

Appealing to adults with more than sex, blood, swears and nudity

As these first few entries prove, some “mature” titles can embody both definitions of the word at once. Blood, gore, nudity and all the rest can coexist with – or even help enhance – the game’s serious adult themes.

God of War is a perfect example. On the surface, Kratos is just another psychopath protagonist; blood-letting, monster-shredding and wench-bedding are the only things that occupy his simple and undeveloped mind. Slaughter this. Sleep with that.

The deeper truth is that, after murdering his own family and being deceived by his own gods, Kratos is completely broken. His self-hatred and desire for punishment are, instead, directed perversely and violently at the outside world. In the words ofSamuel Johnson, “He who makes a beast of himself gets rid of the pain of being a man.”

Yeah, anytime you’re quoting a literary giant to describe a videogame, you know the latter must be about more than “blood, gore nudity and all the rest.”

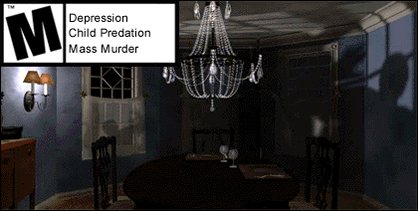

With a fetish for suppressed memories, guilt-ridden heroes and psychologically projected enemies, the Silent Hill series might as well be renamed Freudian Purgatown. People play for the dark, adult themes as much as they do the gruesome blood and gore.

Silent Hill 4 stands out from the rest, though, by using its genre – and its unique setting - to comment on real life nightmares such asagoraphobia(a fear of the outside),hikikomori(extreme social withdrawal affecting thousands of Japanese teens), clinical depression and severe loneliness.

Is the game’s protagonist truly trapped inside his own apartment, or has he isolated himself from the world? Are neighbors actually out of reach, or has he disconnected from them because of mistrust and discomfort? The answers wouldn’t be clear to those suffering from any of the ailments above, and they’re not obvious in Silent Hill 4.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

How dark is this obscure ghost-hunting adventure from the mid-1990s? In the course of just a few hours, you enter the mind and body of three characters: the first is a boy who drowned in a frozen lake, but doesn’t comprehend he is dead; the second is a WWII-era housewife who committed suicide after learning her husband was killed in combat; the third is a gardener who fell in love with a small child, then murdered her after she did not return his affection.

What makes AMBER such a difficult yet rewarding trip, however, is that you don’t know these people’s secrets until you solve them for yourself. When you finally discover the widow’s fate, you’ve been the widow for some time. When the gardener’s evil is revealed, you’ve already experienced and grown accustomed to the world from his perspective.

AMBER does more than create sad, disturbing characters – it forces you to feel their pain and to forgive even their worst decisions.