Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater was James Bond by way of John Rambo

Retrospective | Remembering what made Snake's Soviet-era adventure so special 18 years later

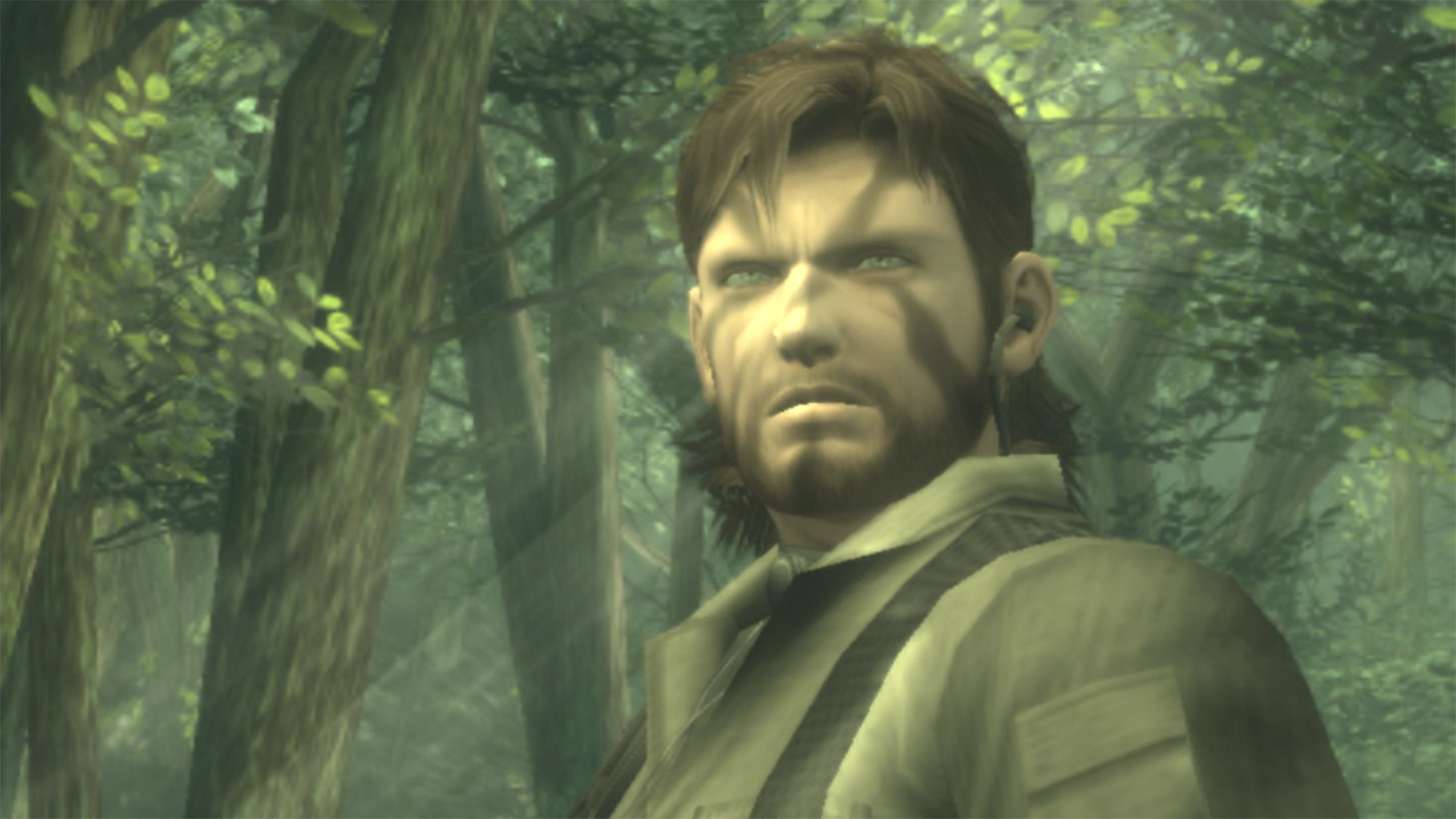

Events begin credibly by Metal Gear standards, not kicking off with a secret island fortress or a giant robot in the Hudson, but a far-off muddy forest and a reasonable Cold War espionage premise. In a lengthy mission before the opening credits, Naked Snake is forced to watch as a US-made atomic bomb delivered by a defector detonates on Soviet soil, and the world is pushed to the brink of nuclear war. Protesting its innocence, the US is given permission from Moscow to dispatch Snake back into the Soviet Union to assassinate the defector, destroy a stolen superweapon and generally do the Kremlin’s cleanup work in a thoroughly deniable manner.

Later, in less plausible events, Snake will fight a ghost and a man made of bees. But before the opening credits signal the end of the Virtuous Mission and the beginning of Operation Snake Eater, everything about Metal Gear Solid 3 lives within boundaries of probability no more outlandish than the ones that have bracketed the activities of James Bond since the late 1950s. It’s been said all too often that MGS3: Snake Eater (later updated and repackaged as Subsistence) was Hideo Kojima’s own take on classic Bond movies, but did James Bond ever suffer so much and fail so often? Dropped from the edge of space, caught in a nuclear blast, stabbed, shot, double-crossed, tortured, partially blinded, double-crossed again, forced to kill his surrogate mother, and double-crossed again, Snake is forged into the bitter and betrayed soldier who will become the series’ antagonist.

By the game’s end, Snake is cast in steel and players along with him, but it’s a story better told with mechanics than narrative, and by the player instead of Kojima. Long before the days of VR missions to teach him which buttons do what, Snake is dropped into the Soviet Union without instruction or tutorial, equipped only with a small pack – and only then if he can find it, since he dropped it mid-descent – and some of the most cumbersome controls ever attached to a console game’s protagonist.

Welcome to the jungle

Rumors about a Metal Gear Solid 3 remake have swirled for years, but they're coming to a head just in time for the latest PlayStation Showcase.

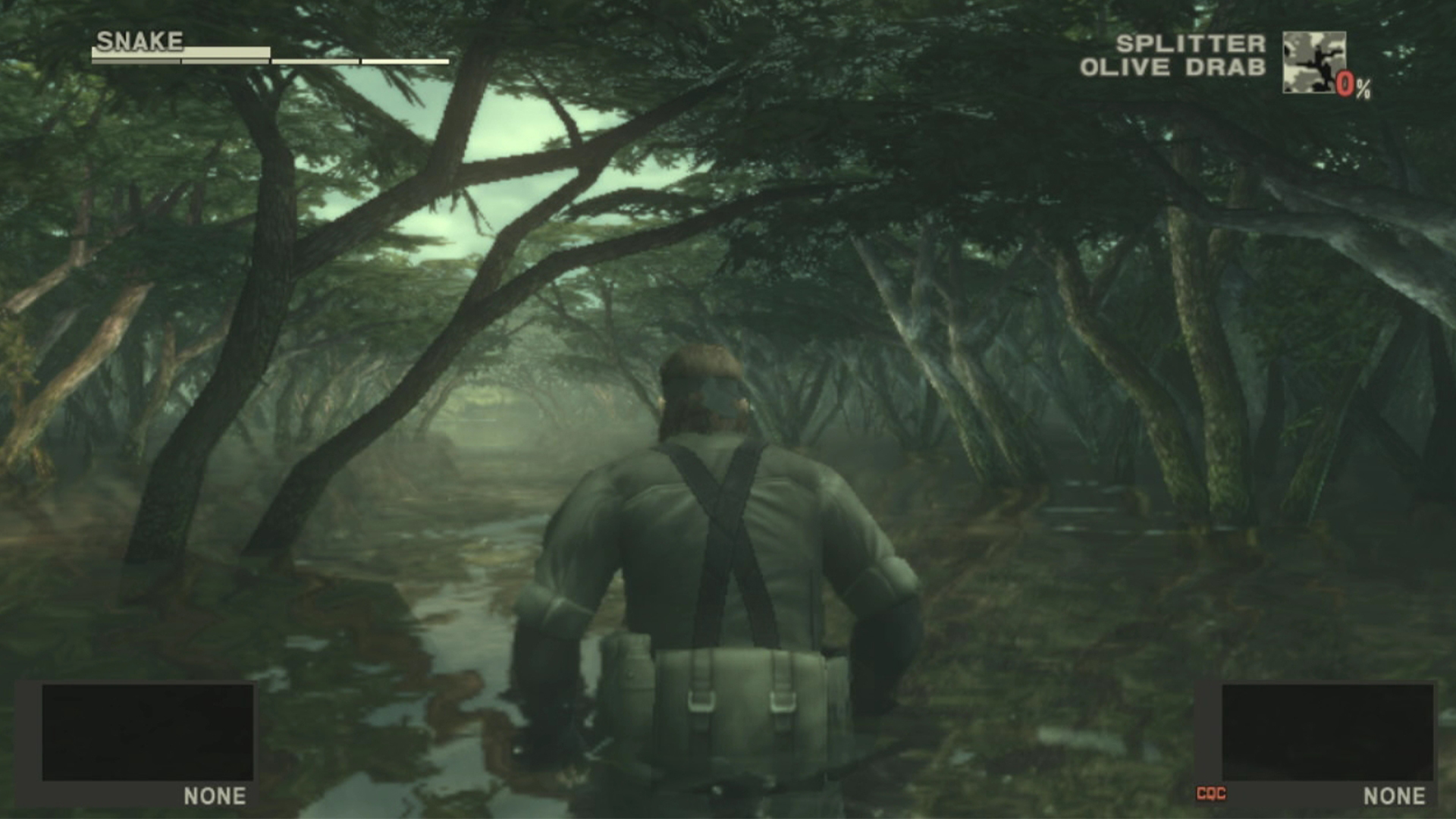

MGS3 is a blizzard of buttons and mechanics, in fact, many new to the series. There’s the new Close Quarters Combat (CQC) system, the new camouflage system, a new system for healing wounds, and a new system for feeding yourself in the wild. MGS3 is a game about survival and Kojima’s team gives you all the tools you need, but next to no advice on how to use them. Every button works in combination with others, most respond to varying amounts of pressure, and few of them do what you’d expect from a game made in the early ’00s. Given a hammer for a needle’s job, players are sent into the forest where most will be betrayed by their controller, promptly taken to the brink of death by an alligator, then finished off by a small patrol in the game’s first open-ended sandbox space.

It’s a contrast to Resident Evil 4’s one- button-for-almost-everything school of game design, which would be popularised by Mikami’s game just a few months after Snake Eater hit shelves. Context-sensitive controls and clear prompts would dominate game design for the next decade, and when Kojima’s team remade Snake Eater for 3DS, one button did most of the heavy lifting. Kojima’s notion – that firing a gun is hard in real life, so it should be hard in a game too – makes a bizarre kind of sense if you’re a determined apologist, but the truth is that Snake Eater was a game behind the times in a number of ways even in 2004.

It’s easy to forget that the first attempt at MGS3 isn’t the game anyone plays today. If MGS2’s corridors and catwalks pushed Metal Gear’s traditional fixed camera to the edge of its limitations, Snake Eater broke it, 100-metre sight lines and expanses of lush green jungle all framed by a camera that could only look down. The first attempt at MGS3 was an ambitious experiment that saw the team that would become Kojima Productions – then an unbranded group within Konami Computer Entertainment Japan – rewrite MGS2’s engine almost from scratch with a mind to releasing the third MGS game on PS3. As the generation grew longer with no sign of bowing out gracefully like those before it, Kojima’s team spent more money than anyone was willing to throw at a folly, and a PS3 launch game became a key component of PS2’s 2004 winter war machine.

But everyone’s fond memories of MGS3 are coloured by its remake. The MGS3 that the gaming world remembers best was born a year later, when Kojima’s team returned to the game and replaced Snake Eater’s top-down perspective with a free 3D camera stationed just behind Naked Snake’s shoulder. With that one change – certainly few cared about Metal Gear Online bundled on a second disc, or the Metal Gear Acid 2 link-up – MGS3 went from being one of the better games of 2004 to being a game that would persist, and subsist, in memory. Viewed from Subsistence’s head-height perspective, Snake Eater’s forest comes alive. Snakes slither in the long grass, frogs climb trees overhead, and alligators prowl the swamps. Distant enemies emerge through the haze without Snake needing to pause in first-person to track them, and a two- dimensional world becomes a three- dimensional playground.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Beyond the chance to see everything up close, the rethought camera introduced something new to the game: time to think. Kojima Productions wouldn’t go so far as to give players anything like a proper tutorial or controls that made sense, but the new camera gave players time to wait, consider, calculate and execute. Viewed top-down, Snake Eater’s world would spring surprises upon the hero – enemies would appear at the screen’s edge as if by magic, bullets would be fired from guns far beyond the camera’s field of view, and a sudden shriek would signal you had been sighted by a guard invisibly positioned just offscreen – but Subsistence’s camera tore down those boundaries. Now you could squat in the long grass and plan, recalling the button combinations that make Snake so powerful, even against a group. You want to take them down? Think. Cross stands up and the D-pad – not the analogue stick – controls silent movement. Holding Circle will grab a trailing soldier (but not too hard or you’ll slit his throat) and quickly releasing Circle and switching to Square will draw your pistol quickly enough to hold up his friends. A single shot will put them to sleep. Now, how do you holster your gun again without dropping the hostage?

Thinking time was Snake Eater’s missing feature. In Subsistence, you could keep one eye on your enemies while hunting for food, spy danger on the horizon and take time recalling the bevy of options in encounters. Hold them up? Throw them down? Stab them? Interrogate them? Choke and drag them? Punch their lights out? Shoot them? Gas them? No. Leave a jazz mag to distract them – and take time to teach yourself the things the game never would. The Subsistence camera seemed to slow the game down, which in turn made players brave. Certainly you couldn’t cram all of Kojima’s lunatic CQC button combinations into your head for those first few fights, but repetition is a good enough teacher and with time to prepare for each encounter you would find yourself recalling the same handful of combinations over and over until muscle memory made you a world-class martial artist and sharpshooter, which was almost certainly the point in the first place.

Steel got it

"A single slip of attention or your thumb on those pressure- sensitive pad buttons and the punishment is severe, and the result is a game that insists upon your absolute undivided attention in a way no game could approach until Demon’s Souls, four years later."

By the game’s end, you are steel. The climactic tests of your abilities – escorting a wounded friend through the forest while being hunted by dozens of special forces soldiers, and a final CQC battle against the woman who taught Snake everything he knows – stretch your abilities to manage camouflage, food, medication, combat and gunplay to their limits. Long ago, Snake was shot by an offscreen Russian because you pressed Square too hard and pumped Kalashnikov rounds into a magpie. In the final moments of Operation Snake Eater, he’s able to tie the enemy AI in knots with CQC, silently tranquillise them from half a map away, baffle them with distractions and beat the in-game originator of CQC to death using her own techniques. There are many memorable moments along the way to those final encounters, of course. There’s the prison escape, the ladder to the mountains, the time paradox, the man made of bees, and the ghost. The single hour-long set-piece fight against The End has spawned more words in print and glowing liquid crystal than most full games from the same era.

They’re good bits, but MGS3 lives in the moments between set-pieces. As Snake endures mutilation and double-triple-cross, the player endures a world that teaches them almost nothing, where it’s possible for complacency to kill even after a hundred successful CQC hold-ups. A single slip of attention or your thumb on those pressure- sensitive pad buttons and the punishment is severe, and the result is a game that insists upon your absolute undivided attention in a way no game could approach until Demon’s Souls, four years later. When you step into the game’s final hour, your skills are your own, taught by failure and persistence – muscle memory forged by the fear of triggering respawning death squads – and when you return to MGS3, the muscle memory is there to greet you. You can’t unteach everything the game thrashes into players, and even a whole decade on, it’s still easy to get lost in that dream, Snake Eater.

This feature first appeared in Edge magazine issue 282. For more fantastic in-depth features and interviews like this, you can pick up single issues at Magazines Direct or subscribe to the magazine, in physical or digital form.

Edge magazine was launched in 1993 with a mission to dig deep into the inner workings of the international videogame industry, quickly building a reputation for next-level analysis, features, interviews and reviews that holds fast nearly 30 years on.