Microtransactions and loot boxes in video games - are they pure greed or a modern necessity?

After the furore surrounding Star Wars Battlefront 2, we investigate gaming's most controversial system

So you’ve bought a full-price game, only to discover that it has the cheek to ask you to spend more money on loot boxes / extra characters / nice hats. The outrage! The sheer indignity of it all! HOW DARE THAT GREEDY PUBLISHER ASK ME TO SPEND MORE MONEY! Quickly, to Reddit, prime the bile cannon, hoist the hot-air sail, launch the hatred torpedoes!

But, wait, wait, hold on a second. WHY are microtransactions in this full-price game? Clearly a large proportion of gamers don’t like them very much (and that’s putting it mildly), so why would a publisher risk its reputation, and possibly sales, by including them? Is it simply greed? Or is it just not possible to make AAA games without microtransactions and still turn a profit?

EA recently received the sharp end of the gaming press - and a decent chunk of outrage from social media - for its inclusion of microtransactions in Star Wars Battlefront 2, which encouraged players to spend money on loot boxes for a chance at getting upgrades for their character. For one analyst at least, this fan furore was massively out of proportion with reality:

“Gamers aren't overcharged, they're undercharged (and we're gamers),” said Evan Wingren of KeyBanc Capital Markets. “This saga has been a perfect storm for overreaction as it involves EA, Star Wars, Reddit, and certain purist gaming journalists/outlets who dislike MTX [microtransactions]. … If you take a step back and look at the data, an hour of video game content is still one of the cheapest forms of entertainment. Quantitative analysis shows that video game publishers are actually charging gamers at a relatively inexpensive rate, and should probably raise prices.”

So are gamers really being undercharged? Let’s look at the numbers.

It’s number crunching time!

How much does it actually cost to make a AAA console game these days? Short answer: a lot more than it used to. And I mean a LOT more.

Whereas publishers are generally happy to crow about a video game’s sales, they tend to be a bit more reluctant to reveal how much games actually cost to make and market - we only have reliable figures for very few titles. But these figures (via Kotaku) are highly revealing of the enormous increase in video game budgets over the past 20 or so years.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

In the late 1990s, the budgets of high-profile console and PC games were generally no more than a few million dollars. Examples include Crash Bandicoot 2 at $2 million, Unreal Tournament at $2 million, Grim Fandango at $3 million, and Thief: The Dark Project at $3 million. Shenmue, with its famously bloated development costs, was very much an outlier at $47 million.

But as we move into the 2000s, budgets regularly hit double-digit millions as development teams expanded to accommodate the higher demands of making games on more powerful consoles. Jak and Daxter on PS2 cost $14 million. Gears of War on Xbox 360 was $10 million. Driver 3 cost $34 million. The genre-defining Half-Life 2 came in at $40 million. Xbox 360 launch title Lost Planet was $40 million. BioShock cost $15 million.

Then at the dawn of the 2010s, game budgets seemed to spiral out of control as dev teams ballooned even further to keep up with ever more complex and technically demanding games. God of War 3 cost $44 million. Heavy Rain cost $40 million. Watch Dogs was $68 million. And Grand Theft Auto 5 cost an astonishing $137 million.

Basically, you’re unlikely to get change from $50 million when developing a modern AAA video game - and that’s without marketing costs, which can often be equal to or even more than the development costs. Square Enix caused general bafflement among gamers in 2013 when it announced that it was “very disappointed” with the Tomb Raider reboot’s initial sales of 3.4 million - a figure that seems pretty high to the layman. But when you discover that the game cost around $100 million to make (it’s not clear whether that included marketing), the publisher’s disappointment makes more sense. The game would have needed to sell 5 to 10 million units to be “truly profitable” according to video game analyst Billy Pidgeon. It eventually scraped into profitability around a year after release.

The falling price of console games

Back in the 1980s, a new NES game cost around $50 in the United States, and perhaps between £40 and £50 in the UK (memorably, Maniac Mansion cost an eye-watering £55 at launch). In the early 1990s, Super NES games cost about the same - between $45 and $60 in the States, and around £40 to £50 in the UK, with Street Fighter 2 coming in at a whopping £65.

Later in the nineties, PlayStation 1 games were generally slightly cheaper than those of the previous generation of consoles at about $40, thanks to the reduced cost of manufacturing CDs compared with cartridges. PS2 games were slightly more, perhaps $50, and PS3 games leapt up to around $60. For the current generation, prices have stayed the same - $60 for new releases.

But although it looks like the price of games has gone up over the past couple of decades, if you adjust these prices for inflation, the cost of games has either remained the same or even gone down. If you take inflation into account, that $40 PlayStation 1 game you bought in 1996 cost the equivalent of $62 in today’s money, so actually slightly more than the current generation of video games. And a $50 NES game from 1989 would be $99 today (ouch, NES gaming was expensive).

But surely more people are buying games now, right?

Good point. From the above figures it looks like games are becoming more and more expensive to make while the cost of buying them remains pretty much constant - which implies that publishers are making less and less money. However, if the overall market for games is expanding, then this would offset the increased development costs, as you would expect to sell far more units of your game.

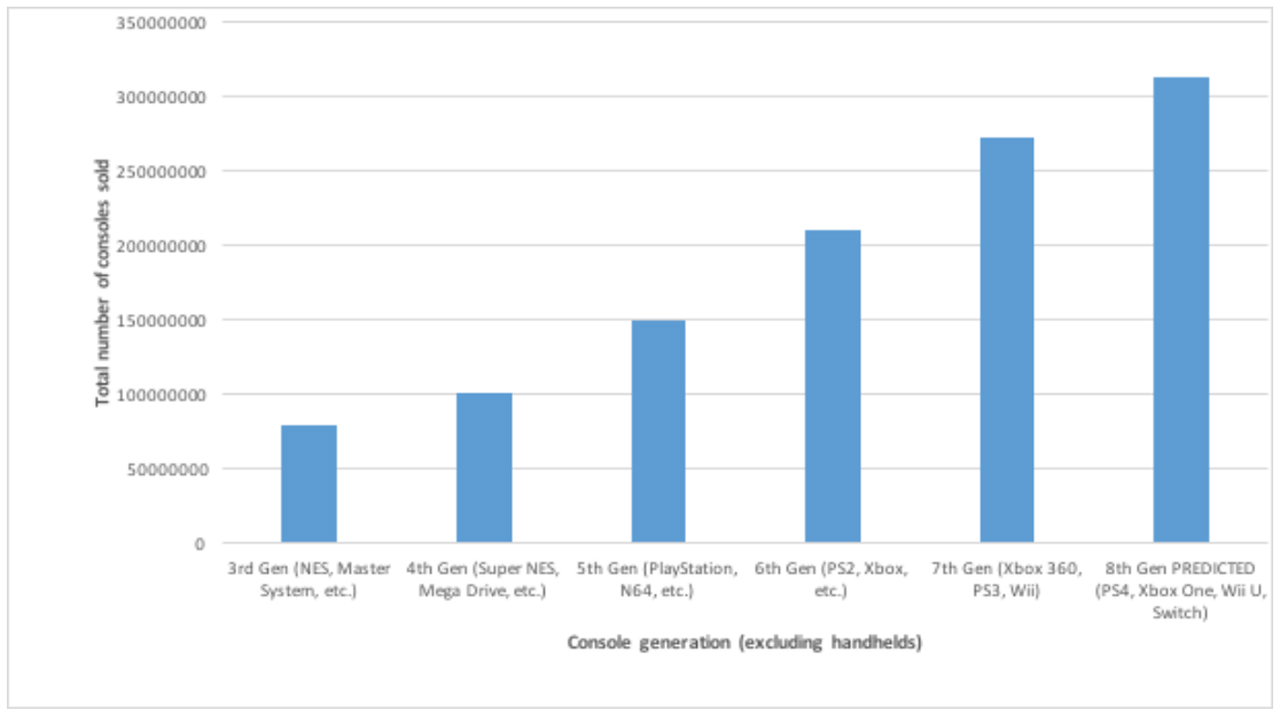

Time for a lovely bar graph!

As you can see, the games market (in terms of total numbers of consoles sold per hardware generation) has expanded steadily over time... But there are signs that this growth may be tapering off. The total sales for the current console generation are:

PS4: 70,600,000

Xbox One: 31,730,000 (estimate)

Wii U: 13,600,000

Switch: 10,000,000

TOTAL: 125,690,000

The predicted total in the above graph is based on the below estimates of lifetime console sales, based on the upper predictions of analysts:

PS4: 130,000,000

Xbox One: 70,000,000

Wii U: 13,600,000 (actual)

Switch: 100,000,000

TOTAL: 303,360,000

Obviously, you have to take these figures with a pinch of salt, as clearly anything could happen over the next few years. But the main point is that even though the console market is still growing, that growth has been roughly linear over the past couple of decades - and with the current generation, the rate of growth may even be slowing slightly.

The cost of developing games, on the other hand, is growing almost exponentially. Compare the budgets of 1997’s Crash Bandicoot 2 ($3 million in today’s money) and 2014’s Watch Dogs ($70.8 million in today’s money) - that’s an increase of more than 2000%. By comparison, the console market (in terms of numbers of consoles sold by generation) grew by around 80% between those years.

Obviously the above examples are just two games, and every game is different in terms of development budget. But in the AAA space at least, the cost of making games seems to have risen much faster than the size of the games market as a whole. In short, the numbers just don’t add up.

So are microtransactions a necessity, then?

Well, the above calculations certainly seem to bear out Wingren’s assertion that gamers are undercharged - many AAA games would have to sell multiple millions of copies at $60 for the publisher to even get back the cost of making them. Jonathan Blow, creator of Braid and The Witness, agrees that games are unrealistically cheap:

I understand the dislike of loot crates (I don't like them either). But a $60 game in 2017 is extremely cheap by historical standards, and most AAA games provide much more play value than games of the past.November 13, 2017

But it’s not as simple as just raising the price of AAA video games to reflect how much they cost to make. We live in a cutthroat capitalist world, after all. Who’s to say the competition won’t undercut you?

Now the problem is: Publisher A eschews loot crates, raises their standard game price to $110. Publisher B keeps the base price at $60 and has crates. Which publisher wins, and which dies?November 13, 2017

Mr Blow has a point. But what’s to stop a publisher issuing a game at two price points? A ‘budget’ version with microtransactions, and a ‘full-price’ version where everything is included? Well, the problem with that is ‘whales’.

The vast majority of players won’t spend a penny on microtransactions - but a tiny percentage of players may spend literally thousands of dollars. In the mobile free-to-play market, whales might make up less than 10% of the player base yet be responsible for 70% of the game’s overall revenue. But this model doesn’t work if there’s a version of the game with all content included for a set price.

Saying no to microtransactions

Despite the spiralling cost of development, some publishers have said that they won’t include microtransactions in their games. CD Projekt RED, developer and publisher of The Witcher 3 and the forthcoming Cyberpunk 2077, said the following in a tweet sent not long after the Battlefront 2 microtransaction fiasco: “Worry not. When thinking Cyberpunk 2077, think nothing less than The Witcher 3 - huge single player, open world, story-driven RPG. No hidden catch, you get what you pay for - no bullshit, just honest gaming like with Wild Hunt. We leave greed to others.”

Cheekiness aside, it’s fair to point out that although CD Projekt RED is against microtransactions, it released two paid DLC packs for The Witcher 3 - and in fact pretty much every AAA game released today has additional, paid-for content of some kind or other. And judging by the figures above, this additional content is pretty much essential for games to turn a decent profit.

Story-based DLC, like the Blood and Wine and Hearts of Stone add-ons for The Witcher 3, is often warmly received by players - but it also costs a lot to make. Extra weapons, cars and skins, on the other hand, cost relatively little to develop. Faced with continuing rises in the costs of development, especially as we enter the realm of 4K gaming, no doubt these relatively cheap paid add-ons will become more attractive to publishers as story-based DLC becomes more expensive to produce.

Then there’s the problem of how to finance multiplayer mega-games like Overwatch and Destiny 2. “In 2018 I think it's inevitable that loot box use in console games will continue to stir controversy, especially as publishers shift their releases across to the games-as-a-service model already dominant in PC and mobile gaming,” said IHS Markit analyst Piers Harding-Rolls in his predictions for the coming year. And indeed, there seems to be an ongoing problem of balancing player expectations with the need to make money in these types of games.

Publishers like Ubisoft are gradually moving across to games as a service. The French giant recently revised its forecast for the financial year ending March 2019, saying it would sell fewer units of its games and publish one less AAA title but still make the same amount of revenue - a trick made possible through delivering continual ‘live content’ for existing games such as Rainbow Six Siege. But what’s the best way to monetize games as a service, like Rainbow Six? The old monthly subscription model of MMORPGs fell out of favour long ago, but somehow the publisher still needs to pay for the continual updates and content additions.

The huge development costs of a game such as Destiny 2 are unlikely to have been met by initial sales of the game - the publisher will rely on DLC and microtransactions to boost it into profit. But a few tens-of-hours of add-on story content might not satisfy a gamer who has already spent thousands of hours with the game, and players (or at least a vocal minority of them) often cry foul when asked to purchase additional content for what they deem to already be a ‘full-price’ game. Yet microtransactions and loot boxes, like the ones in Overwatch, seem to be the only sure way to keep such mega-games going over the long term - at least until a better idea comes along.

Greed or necessity?

EA undoubtedly fumbled the ball with the loot boxes of Star Wars Battlefront 2 - as evidenced by the fact they suspended the game’s microtransactions just before release, following a wave of anger from gamers. But was EA motivated by greed? Or were these microtransactions essential for the game to make its money back?

Only EA really knows the answer to that one. But as the cost of game development rockets upwards, it’s fair to say that unless game prices increase substantially across the board, microtransactions are here to stay in some form or another. That form might not be loot boxes - legal challenges against them, like the one in Belgium, may see them fall out of favour. But it’s clear that as dev costs rise more quickly than the number of people buying games, some form of additional revenue stream other than the game’s cover price will be a necessity.

What form that additional revenue takes - loot boxes, skins, story-based DLC or something else - will ultimately be decided by what gamers prefer to spend their money on. But either way, it seems the money will need to be spent.

Lewis Packwood loves video games. He loves video games so much he has dedicated a lot of his life to writing about them, for publications like GamesRadar+, PC Gamer, Kotaku UK, Retro Gamer, Edge magazine, and others. He does have other interests too though, such as covering technology and film, and he still finds the time to copy-edit science journals and books. And host podcasts… Listen, Lewis is one busy freelance journalist!