Middle-earth: Shadow of War might solve open-world gaming’s biggest problem

Shadow of War remembers your decisions – and its effect on those around you – to create a believable, persistent world

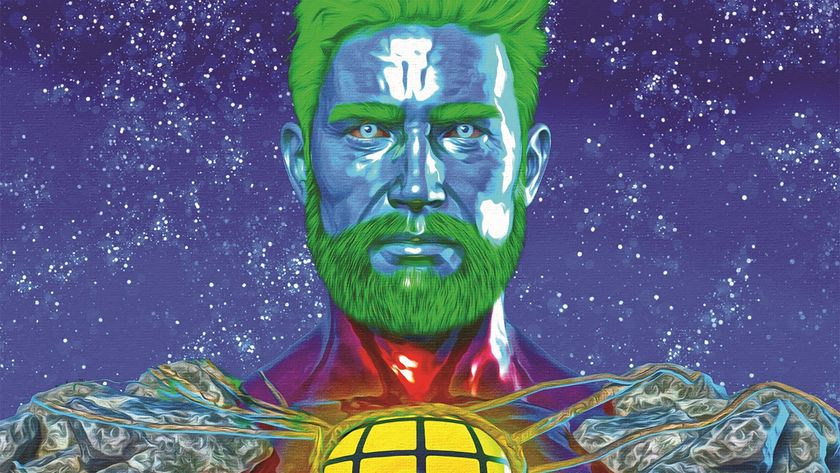

Middle-earth: Shadow of War looks great. Okay, so its odds of kicking up a decent-sized hype cloud were always pretty good, being as it’s the surprise sequel to a surprise hit – the deceptively clever, 2014 open-world action adventure Middle Earth: Shadow of Mordor. Never underestimate the power of a cultish fanbase to grow into a megaton of evangelism given a couple of years’ downtime. But there’s more going on here than that.

Wardor (as it should be called) looks like one of the most smartly and bravely evolved sequels in quite a few years. It didn’t have to be, of course. Given the reputation the original Shadow of Mordor has built in the three years since its release, a more polished do-over would have been fine. It would have been enough to maintain the unique and compulsive Nemesis system – which dynamically generates long-term rivalries and story threads with Orc bad guys based on emergent gameplay interactions such as deaths and kills – while tuning up and filling out the first game’s rather sparse open-world. Make it prettier, up the scale slightly, and done. The goodwill accrued since 2014 would have done the rest.

Bigger ambitions, bigger repercussions

But Monolith Productions looks to be doing much, much more than that. It’s not just scaling Nemesis up, but also applying it to more facets of the game world (relating to both good guys and bad this time around), and creating radical new gameplay elements to service it. Shadow of War, if it goes as well as hoped, could turn out to make its precursor look like a work-in-progress sketch. A test-run of an idea before its full-scale roll-out.

The siege battles are getting all the attention right now, and understandably so. The ability to spread influence and grow resources across the game’s map by using Nemesis-generated ally armies of your own design to take down huge, Helms Deep-style fortresses packed with Nemesis-generated Warchiefs – the cause-and-effect ecosystem of each huge, standout battle defined by the systemic interactions between the various units, trolls, snipers, and dragon-powered flame tanks available to put into play – is a staggering design to behold.

It delivers legitimate, cinematic Lord of the Rings scale with goose-bumping tonal accuracy, but most importantly, it creates the specifics of those set-pieces (the trials, dangers, tactical advantages, and clutch, NPC saves) organically, building the layers of each battle out of your actions in the game so far. Each of these sieges promises to be a flashpoint that crystallises all of your previous decisions, wins and losses, weaving potentially dozens of hours of previous gameplay and story threads into a distinct and dramatic battle tapestry.

Solving old problems, building better worlds

But it’s not just the specifics of Wardor’s big new addition that excites me. Rather, it’s the fact that the philosophy behind the design seems to directly address a problem that’s quietly nibbled at the toes of free-roaming action games for years. Namely the difficulty of making an open-world feel like a real world – and how they pander to the player, in an often unbelievable way.

In some respects, games have been getting better at this ever since the genre’s conventions were first established in Grand Theft Auto 3 in 2001. Those particular respects though, have largely remained within the realm of the visual and the architectural. Open-worlds have become bigger, more detailed, and more vibrant with each passing year, but in terms of creating a real, living, breathing world to freely exist and play in, that’s only half the battle. In striving to create some kind of believable continuum, open world games have been concentrating on the space, but less on the time. In short, a sense of wider, reactive causality has long been the genre’s failing. Cause as much trouble as you want in Grand Theft Auto. Enrage any mob boss you like. A quick police chase later - at most - and it'll all be forgotten, the world reset to the status quo as if you never lifted a finger.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

In fact greater visual and spatial fidelity has only made this issue more apparent. As open-worlds have come to look more real, the unreality of their workings has become clearer by contrast. While they may have the trappings of bustling, thriving places, the lack of persistent cause-and-effect, of a society operating outside of the player’s actions, has tripped up that aspiration.

It’s not an easy thing to craft in a video game, particularly in the action-driven field in which most open-world games stand. With the physical structure of their worlds so inherent to the construction of their gameplay – whether scripted or fashioned by player discovery – and that gameplay so frequently focused around violence and destruction, it’s hard to give player actions any lasting effects without entirely breaking the game. Any manner of straightforward, persistent effect would be at the expense of long-term play. For example, the average player might reduce GTA: San Andreas' Los Santos to a pile of useless rubble in a matter of days.

Some games have delivered fun but slightly cheesy workarounds in this area, but as enjoyable as laying waste to one’s surrounds in a game like Mercenaries 2 undoubtedly is, there’s an extra layer of wreckage that comes with the act, this time in respect of the fourth wall. It takes a fair bit of concentration to ignore the invisible construction crews rapidly repairing every downed building in the player’s absence, in order to keep the game playable.

Not that there isn’t a way of making that stuff permanent, using the destruction and / or liberation of enemy enclaves a means of recording progress. The likes of Red Faction: Guerilla, Far Cry 3 and Mafia 3 make this a fundamental element of their game-flow. But, again, with long-term play there’s a downside to this approach. Rather than giving the player the sense of existing as part of a wider, organic world, it increasingly creates the feeling that the city, planet, or dragon-strewn fantasy world in question revolves around, and exists purely for, the player. Which it does, but that’s not the point.

The world is yours. But it shouldn't be

The open-world conceit dictates that you’re part of a bigger picture, but in practice, nothing happens unless you make it happen directly. For all the profession of far-reaching machinations and organic reality, things remain static until the player dictates that they don’t. And that’s also the case in every linear game ever made. Open-world games should be striving for a greater illusion. That’s surely their point. They should aim to be more than a video game Truman Show, and push for a greater, more grounded sense of reality.

So if physical persistence is too difficult an option to wrangle, then player-driven, narrative persistence is a better ideal to pursue. And, while largely lodged within the realm of the western RPG – rather than the more action-focused likes of Gotham or New Austin – there are some great examples of narrative causality knocking around. The Witcher 3 is probably the best, most recent treatment of the idea, and we’re likely to see a great deal more of it in Mass Effect: Andromeda.

Done right, with enough long-term repercussions built in (CD Projekt Red’s greatest strength is its willingness to blindside the player with ‘didn’t see that coming’ moments, hours after decisions are made), this sort of design can be powerful and gratifying, grounding the player in a story with a very real feeling of connection. Your decisions accrue weight and emotional consequence, through a heavy sense of responsibility.

Such decisions, however, won't fix the conundrum of the player being – unsatisfactorily – made the centre of the universe. Villages may burn as a result of your actions, and your carefully chosen dialogue responses might inadvertently make or break royal careers, affecting the livelihood of entire regions in the process, but there’s still a mechanical air to the way it all works out. It still feels less like interacting with a thriving ecosystem, more like walking around with a remote control for the planet.

Controllable chaos

Shadow of War, by contrast, feels like a game striking a very canny balance. By expanding the scope of the Nemesis system to let natural, action-driven moments and systemic causality feed into the wider state of play, as well as more traditional, on-the-spot decisions, it has the potential to give the player enough direct control to feel like this is their, personal story, but without making it feel personally dictated. Just like in real life, there should be direct influence over immediate, moment-to-moment events, but more than enough chaos dictating the wider world as to create a sense of cutting a path through an organic, independent society, rather than ticking pre-determined boxes on the way to unlocking a win.

Shadow of War maintains a sense of ownership over your experience without fashioning a sense of ownership of the world. It turns player input into stimulus for fuelling a self-governing ecosystem, and then steering those bigger outcomes back into the circumstances surrounding immediate, player-driven action.

Say, for instance, you convince a troll to change sides and join your army. Say you deploy him to help breach an enemy fortress, and he goes smashing straight through an inner door at a later point in the battle, because that’s just what trolls do. Say he then gets injured by a dragon you didn't know was waiting on the other side, and he feels betrayed. Say the resentment grows, and he later turns against you, and eventually you have to fight him along the way to taking out a bigger target. A simple, player-instigated event starts a ripple, game systems take over, and suddenly you have an entirely unpredictable sub-plot on your hands, with real gameplay implications.

In relation to the video game’s traditional Hero’s Journey conceit, that could be a game-changer, both in terms of immersion, and in terms of creating the feel of a real, organic journey written with real, personalised achievements.

After all, it’s hard to maintain suspension of disbelief in the tale of a put-upon, rising would-be hero when all the dice are pre-loaded and the world pre-scripted to fall at your feet, exactly as you wish it to. Instead, Shadow of War looks to be aiming for the hithero unexplored sweet-spot of reducing the sense of control without removing the means of control, ensuring that you’ll always be able to handle whatever’s coming up, but that the world, doing its own thing on its own terms, will decide what is coming.

Again, much like real-life, but with more dragons. And there can, at the end of the day, be little higher aspiration for a video game than that.

5 years after Avengers, 2 years after its last layoffs, and who knows how long before Perfect Dark and Tomb Raider return, Crystal Dynamics announces another round of layoffs

Getting Assassin's Creed Shadows on PS5 and Xbox Series X was all about adding "dynamism" to the open world, but the devs seem most proud about the trees