Movie By Movie: Steven Soderbergh

From Sundance to superstars with Hollywood's indie innovator

Sex, Lies And Videotape (1989)

The Film : Hand-written during an eight-day road trip by a Soderbergh hovering on the fringes of the filmmaking industry. sex, lies was the film that jump-started the same early '90s US indie wave that carried the likes of Spike Lee, Quentin Tarantino and Kevin Smith to prominence.

The film itself is an intense, erotically-charged drama that's intellectual rather than explicit, Soderbergh's smart, sleazy script brought to life by four measured lead performances.

It was the perfect fit for Manhattan distributor Miramax, who scored their first big hit with the indie, which won the Palme D'Or at Cannes. Sickeningly, Soderbergh was just 26.

Soderbergh Speaks: “When I arrived in Los Angeles, I gave the script to my agent, not knowing what she would think. She liked it a lot and the positive reaction on the part of the producers was pretty immediate - to the extent that this was a film about sexuality, with four young and attractive characters, which could be made for just about one million dollars, which is not a great deal of risk.”

Kafka (1991)

The Film: With Hollywood at his feet, Soderbergh swerved left. He could have made whatever he wanted – he chose to make a black and white literary drama weaving together the fictional works and biography of Franz Kafka, starring Jeremy Irons.

Shadows of The Third Man loom large across Soderbergh's cobbled Prague streets, and there's more than a little of Orson Welles' own Kafka adaptation The Trial here too. The film occasionally sparks into haunting life, but generally it's an atmospheric misstep.

The film grossed little over a million dollars, and having been lauded as the next big thing, Soderbergh was on the end of a critical kicking.

Soderbergh Speaks: “I thought a biography of Kafka would be boring. As for Kafka's books, they have certain faults as cinema material - as a reader, of course, I feel differently and am very interested in his themes. The script seemed to me to escape all the traps of a biography and of an adaptation, while keeping all that seemed interesting to me: the foreshadowing of Nazism by 20 years, the bureaucratic thinking leading up to the Third Reich.”

King Of The Hill (1993)

The Film: An underrated and overlooked period drama. Though it received mostly positive reviews, King Of The Hill was too soft and too sentimental to jolt Soderbergh out of his post-Kafka downwards spin.

A shame, because it's beautifully made. There's a strong lead turn from 14 year-old Jesse Bradford as the home alone Depression-era kid making out for himself in a crowded tenement building, and an eye-catching early show from Adrien Brody.

Soderbergh Speaks: “King Of The Hill was hard work. I staged it and shot more film than I had ever before, with a script that was unusually long. The film had a more open structure than the first two, and I constantly had to solve problems. The shooting was exhausting because I really had nobody to back me up, although I can't say there were no pressures on me.”

The Underneath (1995)

The Film: A tired, fractured remake of Robert Siodmak's Criss Cross. It was Soderbergh's third strike, signalling the onset of his premature mid-career crisis.

Starring sex, lies' Peter Gallagher, The Underneath is a small town noir about betrayal and heartache. It falls flat, but interestingly contains hints of the cold lens work and woozy plotting that would characterise his later work.

Soderbergh Speaks: “I had a conflict with the Writers' Guild, following a ruling they passed on the script. I couldn't object anymore so in order to voice my dissatisfaction, I signed using a pseudonym using the name of one of one of the characters in Brazil. That seemed an appropriate response to the bureaucracy.”

“It's the coldest of all the films I've made. There's something somnambulant about it. I was sleepwalking in my life and my work, and it shows.”

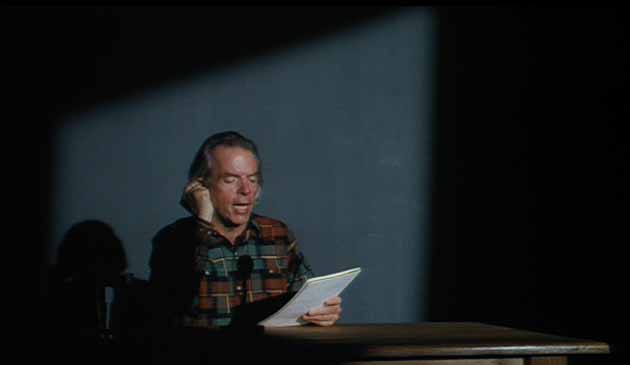

Gray's Anatomy (1996)

The Film: In total creative flux and doubting his own abilities, Sodebergh collaborated with actor and performer Spalding Gray, filming one of Gray's typically neurotic monologues.

The film is funny and simple, and a much-needed break from the pressures of fully-fledged filmmaking for a stumbling Soderbergh.

Soderbergh Speaks: In the midst of his creative crisis, Soderbergh struggled with making - and selling - a straight performance film: “Cutting the Gray's Anatomy trailer. I have no idea how to do this, other than trying to avoid shots of Spalding talking.”

Schizopolis (1996)

The Film: A dense, lunatic working-out of Soderbergh's creative and personal crisis, Schizopolis is a self-financed experimental comedy in the style of Richard Lester's wonderfully chaotic '60s knockabouts.

Barely made for public consumption, the film makes little obvious sense. Soderbergh stars – twice – as a man whose wife (his real life ex) is having an affair with his doppleganger. “Oh no!” he shouts with triple meaning at one point, “I'm having an affair with my own wife!”

The film veers between the hashingly awful and the absurdly brillliant, and above all conveys a hell of confusion and miscommunication, with Soderbergh and wife exchanging descriptions of what normal people say to each other (“Generic greeting!”) and one whole scene replaced by a card bearing the words “Idea missing.”

Soderbergh Speaks: “When I finished Schizopolis, I honestly thought - I need to come up with a German word for this, too - I honestly thought that I was really onto something that was going to be very, very popular. I thought that movie was going to be a hit. I thought people would go, “This is a new thing.” Once I started showing it, I didn’t believe it anymore.”

“Schizopolis was an exercise in verbal and narrative abstraction, Gray's Anatomy in visual abstraction, and both of them defined the edges and gave me a shape to work within that I hadn't had before. They've both informed every film that I've made since.”

Out Of Sight (1998)

The Film: Soderbergh's rebirth. A twisty crime caper based on an Elmore Leonard novel brought to him as a complete project by producer Casey Silver while the director was floundering in a sea of uncredited script rewrites (Mimic, Nightwatch).

The film rested on the intense chemistry between the leads – Jennifer Lopez as a foxy cop, and George Clooney (in the first of many collaborations) as a charming con who gets past her defences.

Full of the energetic fizz of Schizopolis and none of the madness, Out Of Sight was not only a (modest) hit, but brought Soderbergh's career back to life.

Soderbergh Speaks: “I guess it was self-evident to everybody that if I did it, there was no way I wasn't going to pee on it. It was going to have my stench no matter what. Fortunately that's what they wanted. Jersey Films made it clear they had no desire to make Get Shorty 2.”

“Had I not made those movies prior to Out Of Sight, I wouldn't have made Out Of Sight the way I did. I'm still lucky I had the luxury to make those things first, but I was definitely feeling I was marginalising myself. I didn't mind being an art-house failure, but I didn't want to spend my whole life there.”

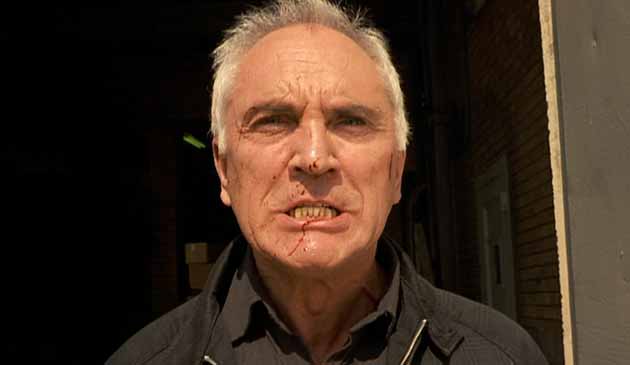

The Limey (1999)

The Film: Flowing with confidence, Soderbergh's comeback follow-up was like the dark twin of Out Of Sight – another twisty neo-noir thriller, but this time much darker and more fractured.

Point Blank is clearly an influence – not just the dreamy timeline, but the revenge-driven story (Terence Stamp's steely ex-con investigating the death of his daughter). But unlike Kafka, overshadowed by its inspiration, The Limey stands alongside its predeccesor.

It wasn't a financial success – it cost $10 million, made just over $3 million – but that didn't matter so much as the swagger and intelligence Soderbergh pumped into it. He was unmistakably back.

Soderbergh Speaks: “My whole line while we were making it was, 'If we do our job right this is Get Carter as made by Alain Resnais,' which I know spells big box office! I felt I could get away with a certain amount of abstraction because the backbone of the movie is so straight. Even so, my first version was so layered and deconstructed even people who had worked on the movie didn't understand it.”

Erin Brokovich (2000)

The Film: The big time. By this point Soderbergh was working fast and fluently, and his third film in as many years was this unpatronising issue drama starring genuine A-lister Julia Roberts.

Roberts was earnest and stubborn as the hard-working single ma campaigning for victims of water supply poisoning, and led the film to the biggest box-office numbers of Soderbergh's career – over $250 million worldwide.

She also won the Oscar for best actress, while the film was nominated for best picture and Soderbergh for best director.

Soderbergh Speaks: “If you're trying to sneak something under the wire, by which I mean an adult, intelligent film with no sequel potential, no merchandising, no high concept and no big hook, it's nice to have one of the world's most bankable stars sneaking under with you.”

Traffic (2000)

The Film: This complex weave of drug trade lives and locations (a remake of Channel 4 series Traffik) was Soderbergh's most ambitious and expensive film.

It follows a tangled ensemble of impressively authentic and conflicted characters – Michael Douglas' grandstanding politician dealing with his daughter's addiction, Benicio Del Toro's Mexican cop uncovering corruption in the anti-drug war – spread from the American Midwest to the South American slums, Soderbergh using camera filters to colour code each episode.

It was the biggest financial success of the director's career, earning an Oscar nomination for best film (alongside Erin Brokovich) and a best director win for Soderbergh himself.

Soderbergh Speaks: “I'd been refining my idea of doing a run-and-gun movie over the last couple of films, trying to make things more naturalistic, and this seemed to be the one to do it on, because of the subject matter, the size, and the short schedule.”

On pitching the script, “It was hard for me to describe what it is and who the audience was going to be. It's not an unreasonable thing for someone who is spending $40 million to ask, 'Can you give me a taste of what's in store?' So I talked about things like The French Connection.”

Ocean's Eleven (2001)

The Film: Issue movies in the can and Oscar in the bag, it was time for some down time. Roping in the A-listers who'd lit up his string of successes (Clooney and Roberts, joined by Brad Pitt, Matt Damon and Andy Garcia) Soderbergh crafted an effortlessly breezy and brilliantly enjoyable heist romp.

It sparkles, it charms, it barely means a thing – and then it's gone, just the film's band of thieving heroes.

Soderbergh Speaks: “Our whole idea was, 'Remember those Irwin Allen movies with 15 stars – wouldn't that be cool?' There's only one way to do it – come up with a formula that everybody adheres to. And the bottom line is, nobody's getting what they normally get, up-front or in the back-end.”

Full Frontal (2002)

The Film: Self-indulgent? Maybe just a little. Billed as the spiritual sequel to sex, lies, Full Frontal is a spontaneous New Wave-y drama-doc following the cast and crew of a fictional Hollywood production.

Attached to the script were ten rules for potential cast members (driving themselves to the set, doing their own wardrobe and makeup) and the film is clearly at pains to be playful, smudging the line between fiction and non-fiction with a series of cameos (David Fincher and Brad Pitt) and criss-crossing storylines.

It never quite pulls it off – it's too stagey and, in the end, boring – or lives up to the sex, lies 2 billing, but it's an interesting side-note all the same.

Soderbergh Speaks: “It’s a live-action discussion about the phoniness of aesthetics, and at the end of the movie the wrong aesthetic is exposed as being phony, the one that you think is real. And so it pisses people off, because basically the movie’s just saying you shouldn’t be too pulled in by any of these tricks.”

“At the time, I was interested in the contract between the filmmaker and the audience. What’s the fine print? What are you allowed to do and not to do? For two million dollars, let’s find out. And I learned something—I learned that, for most people, I really went off the reservation there.”

Solaris (2002)

The Film: A twitching hybrid – a remake of the cerebral Andrei Tarkovsky original (it's like a Soviet 2001, with all the mechanical detachment that implies) produced by Aliens director James Cameron, with Soderbergh in the middle.

The result splits opinion: either Soderbergh's most elegant and honest film, with Clooney in shattering form as an astronaut encountering visions of his dead wife, or an over-emotional fumble of material too intricate for coarse Hollywood hands.

Soderbergh Speaks: “I'm a big fan of Tarkovsky. I think he's an actual poet, which is very rare in the cinema. The fact that he had such an impact with only seven features, I think is a testament to his genius. I really loved the film. I didn't feel his film could be improved upon. I really just had a very different interpretation of the Stanislaw Lem book, which has a lot of ideas in it, enough I think to generate a couple more films.”

Ocean's Twelve (2004)

The Film: An unconvincing return for Clooney's band of blaggers. The trouble is that it's not content just to roll out the ideas and celeb smiles of the first, and instead tries to marry the flash and dash with Soderbergh's more intellectual interests.

Like? Like the nature of celebrity and the meaning of 'real' in film. So the movie is presented in flimsy Full Frontal-style handheld, and its most crucial scene turns the fiction inside out – Bruce Willis arrives playing himself, interrupting the gang pretending that Tess (played by Julia Roberts) is Julia Roberts.

Smart Sixth Sense gag aside, it's look-away cringey. All we wanted was a magic trick. We'd have to wait for Thirteen...

Soderbergh Speaks: “Making a film that's supposed to be fun to watch is really hard - that's the weird irony of it. I had more fun making Traffic than either of the Ocean's films. It's harder to come up with ideas of how to do stuff. You've got this huge machine, but you want the whole thing to feel breezy and light. That's really weird. But I wanted to do it because I felt there was somewhere else to go. It's a very, very different film than the first one.”

Bubble (2006)

The Film: There are some things you can't unsee, like the stretched, inflated baby heads in Soderbergh's low-budget experiment just as their eyes are inserted. Fshhhh-POP.

The image is one of a handful of striking, memorable touches in an otherwise quiet film. It's a murder drama, made with improvising non-professional actors in Ohio, the best of whom is chillingly inscrutable lead (and potential suspect) Debbie Doebereiner.

The film was part of a six picture deal Soderbergh made with 2029 Entertainment to explore the possibilities of simultaneous releases across cinema, DVD and television. They haven't done it again. It went badly.

Soderbergh Speaks: “The original idea came from a news story the writer and I had seen - [a] woman who went into an ER with an infant and said, 'I just gave birth to this baby.' She was covered in blood. 'I just gave birth to this baby, would you help me?' The ER people knew immediately something was wrong. It turned out she’d killed her friend at work, who was pregnant, and took the baby out of her stomach and brought it to the ER. And this was all because this woman wanted a baby and was jealous that her friend was having one. This was the craziest thing I ever read.”

The Good German (2006)

The Film: Great success allows you to indulge in great failures, and financially The Good German was certainly a failure. A black and white thriller set in Berlin during the end of World War Two (further hints of The Third Man), the film painstakingly recreated classic film techniques (it was presented in pre-widescreeen academy ratio) but returned just $6 million on a budget of $32 million.

The film itself is impressively staged – the studio-era lighting and composition showcasing the classic screen looks of stars George Clooney and Cate Blanchett – but the plot doesn't stick, and it's more curiosity than anything.

Soderbergh Speaks: “That kind of staging is a lost art, which is too bad. The reason they no longer work that way is because it means making choices, real choices, and sticking to them. That's not what people do now. They want all the options they can get in the editing room.”

Ocean's Thirteen (2007)

The Film: When working on their less commercial films, Clooney and Soderbergh would often joke, with charming self-deprecation, that if it didn't work they could always do “another Ocean's.”

The experiment of Bubble aside, Soderbergh's slate coming in to Ocean's Thirteen had a clear 'one for them, one for me' shape to it that pin this second sequel a confidence and coffers-restoring payback for The Good German.

It's an improvement over Twelve, with the flash and swagger of the first partially restored, and a killer villain added in the shape of Al Pacino. Could've gone easier on the Godfather references though, fellas.

Soderbergh Speaks: “It was kind of sad near the end of it to go, 'Well, this is the last time I'm going to see these people in a room. I really like them all and they really like each other, and there was a very strong sense that we were really lucky that these movies came about and we were able to do them and this was it.' At the end of it, there was a real sense of passage and wondering for me whether I'll ever find another commercial movie to make”

Che (2008)

The Film: A complex and ambitious epic based on the life of Che Guevara, which reteamed Soderbergh with his Traffic star Benicio Del Toro.

Del Toro was the driving force behind the project, having initially brought the script to Soderbergh during their first film together. Eventually the Spanish-language monster was broken into two parts – The Argentine and Guerrilla – with a combined running time of over four and a half hours.

The production wasn't always a happy one for Soderbergh, and the finished film doesn't have the graceful intelligence of Traffic. But Del Toro is mesmerising in the lead, and there's an intensity here that's unique among Soderbergh's work.

Soderbergh Speaks: "This is a political film in the sense that there's an ideology that's being expressed, but that isn't what drew me to it ultimately. I'm obviously not a communist. As I said to someone several weeks ago, there isn't even a place for me in the society that Che was trying to build. Literally, he says there is no great artist who is also a great revolutionary. He didn't have a lot of use for the work that I do. Personally, he probably would have hated me."

The Informant! (2009)

The Film: After the grandiosity of Che, Soderbergh follow-up treats what could have been an equally serious subject - corporate crime and whisteblowing - with the director's dark, irreverent humour.

Based on Kurt Eichenwald's book of the same name, The Informant! tells the true story of bipolazr exec-turned-supergrass Mark Whitacre, who helped the FBI close in on a major price fixing conspiracy in which he himself was heavily implicated.

Bringing Whitacre's cracked perspective to the fore, the film is a jagged rush of the unlikey and the inappropriate, with a chubbed-up Matt Damon (carrying 30 extra pounds) as the increasingly frantic tattle-tale. "I think I lost my Sexiest Man Alive title," the star joked.

Soderbergh Speaks: “I didn't meet Whitacre. I didn't want to meet anybody who was involved with the story. I had the facts and so I didn't really want to get in to discussions with people about what things meant.”

“It wasn't immediately clear to us that it should be a comedy. That kind of came out of discussions in which I was describing more often than not what I didn't want it to be like. I didn't want it to be like The Insider. I didn't want it to be like Erin Brockovich. I wanted to separate it from those films.”

The Total Film team are made up of the finest minds in all of film journalism. They are: Editor Jane Crowther, Deputy Editor Matt Maytum, Reviews Ed Matthew Leyland, News Editor Jordan Farley, and Online Editor Emily Murray. Expect exclusive news, reviews, features, and more from the team behind the smarter movie magazine.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!