Putting the toys away

As you may have heard, THQ is no more. The once giant publisher has finally completed its long, merciless road to dissolution through a piecemeal auction that saw the majority of its remaining studios and IPs fall into the hands of its former competitors. And while the writing had been on the wall for THQ for many months prior, seeing a former pillar of the industry disappear for good can still be depressing--especially when many good peoples jobs disappear along with it.

So lets pour one out for THQ, finding out just how it came to flourish and flounder in the process. Here is the history of a company thats dead, but not forgotten.

Toy Head-Quarters starts off in Neverland

The beginnings of THQ technically trace back to early 1990, when Jack Friedman founded the company known as Toy Head-Quarters, or T*HQ. Friedman was experienced in gaming at the time, having co-founded the former toy and video game publisher LJN, but formed T*HQ as a toy company with his initial investments. A few months after establishing the company, though, Friedman steered T*HQ into the world of gaming by acquiring the video game segment of Broderbund, a video game company best known today as the group behind Jordan Mechners original Prince of Persia game.

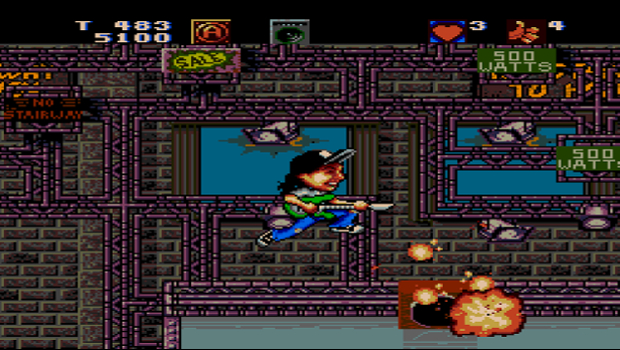

In 1991, T*HQ released the first of its many eventual titles: Peter Pan and the Pirates. Yeah, not exactly memorable. The side-scroller was based off of the animated movie of the same name, and kicked off a string of licensed titles that T*HQ would rely on over the next few years. T*HQ would merge with the Trinity Acquisition Corporation, a publicly-traded company that had been raising money without a real M.O. at the time, by the end of the year. It was growing.

Its all about the licenses, baby

T*HQs earliest hits in both the toy and game market were based on existing IPs. Friedmans previous company, LJN, was known for its catalogue of licensed games--ranging from the great WWF RAW to the horrid Friday the 13th--so the CEOs strategy wasnt exactly untested at the time. T*HQs plan was to gobble up licenses that would appeal to young audiences and turn them around into toys and games as soon as possible to assure relevancy. Products were made on the cheap and sold through big-name retailers so that a potential failure would not devastate the company.

This strategy wasnt exactly unique to T*HQ, but for the most part, it worked. Like its competitors, T*HQ benefited from being licensed by Nintendo to sell and market its games for the NES and Game Boy. By the end of its first year of game publishing it had hit $33 million in sales. This Toy Headquarters seemed shrewd and sharp; its blend of video games, board games, and action figures (Vanilla Ice! Kevin McAllister!) wasn't original, but it was doing well enough. Things were looking up.

Things begin to slide

Then they werent. T*HQ continued its rapid licensing strategy into 1992, getting licensed by Sega to publish for its systems alongside Nintendos, although most of T*HQs efforts would stay with the Big N. It even acquired its first developer, Black Pearl Software, later in the year. Games based on Waynes World, Ren and Stimpy, Swamp Thing, and other IPs were released, and sales figures continued to grow. This was good.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

But creating lots of games requires lots of money. The cost of producing all these products and herding all these licenses grew alongside the sales of the games themselves. The companys greater emphasis on Super Nintendo games also faltered as the Sega Genesis proved the more popular console in the US. Profits began to shrink, and eventually turned into multi-million dollar losses. T*HQ attempted to salvage its dough by selling stock, shaving the salary of its executives, and even dropping production of its regular toys to focus squarely on games, but more drastic changes were needed. So in 1995, founder Jack Friedman stepped down from his position as CEO, and a new leader took T*HQs reigns.

The Brian Farrell reign begins

That leader was chief financial officer Brian Farrell, a man who would serve at the top of THQ until its ultimate demise. He almost immediately made changes to the companys structure, firing half of T*HQs then 60-man staff while simultaneously ramping up the speed and quantity of game development. Harsh.

But Farrell, who had taken control right around the start of the fifth generation of consoles, had a new direction in mind. While the industry collectively fawned over the power of the Sony PlayStation, Sega Saturn, and Nintendo 64, T*HQ would instead cater to the many gamers who stuck with last-gen systems. It fired off a veritable army of games in 1995 and 1996 for older consoles and struck up deals with more established licensors to produce them on the cheap. Games like The Mask (yes, the Jim Carrey one), Mohawk and Headphone Jack, Time Killers, and others werent ever going to set the world on fire, but they cost under $15, which was good enough for many SNES and Genesis holdovers. The low-risk onslaught of titles quickly put T*HQ back in the black. It was then time to jump into the next generation.

T*HQ becomes THQ and enters the 64-bit era

THQ was almost completely into the 32/64-bit era by 1997. It had dropped that weird asterisk/dot thingy from its name, acquired a few new companies as part of its recovery efforts, and brought its fast and furious licensed games strategy to the PlayStation, Game Boy, PC, Saturn, and Nintendo 64. A few of these games were alright, like the PS1 adaptation of Ghost in the Shell, but for the most part, THQ wasnt doing any favors for the gaming communitys perception of licensed games. And as for the other efforts, we doubt many of you fondly remember titles like Vs., Bravo Air Race, or K-1: The Arena Fighters.

Other games based on popular films (Hercules, The Lost World: Jurassic Park), and actual sports (the Brunswick Circuit Pro Bowling series, the Bass Masters fishing games, and later, the Championship Motocross series) also made their expected money, but werent doing much beyond that. But thankfully, there was one type of game THQ would come to revolutionize in the late 90s--a genre that it would stay with until the bitter end.

The wrestling wars layeth the smackdown (and bring in millions)...

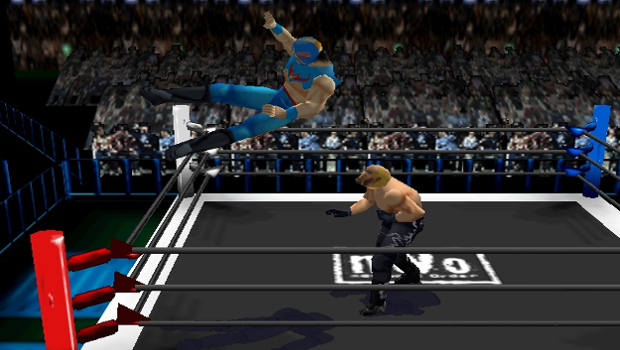

That genre, of course, was wrestling. THQ had secured a crucial licensing agreement with Ted Turners World Championship Wrestling, and in 1997 released two games starring Hulk Hogan, Sting, and the gang: WCW vs. the World for the PlayStation, and WCW vs. nWo: World Tour for the Nintendo 64. Both developed by the AKI Corporation, it was the latter of these two that took the gaming world by storm--and raked in tens of millions of dollars for THQ.

Its innovative grappling system became the genres gold standard, and its roster of WCW stars took full advantage of the wrestling craze of the time. It was also a near-clone of its Japanese counterpart, Virtual Pro Wrestling 64, but hey, it was still fun.

...but EA smelled what THQ was cooking

World Tours sequel, WCW/nWo Revenge, improved nearly everything about the original, and became the highest-selling non-Nintendo game ever released for the Nintendo 64. More wrestlers followed, but unfortunately for THQ, its success caught the eyes of those dastardly folks at Electronic Arts.

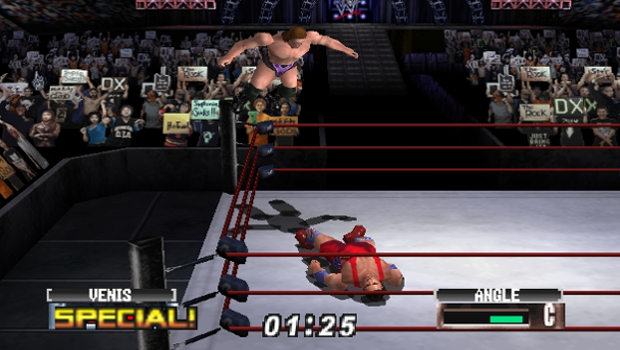

EA soon scooped up the WCW license from Farrell and company, but THQ countered by getting another one of its own from WCWs chief rival, the World Wrestling Federation. That snag eventually resulted in classics like WWF No Mercy and the WWF SmackDown! series, which won the hearts and wallets of millions of gamers for THQ. The WWF wound up buying the WCW in 2001, and THQ would go on to make hits based on Vince McMahons clan each and every year until it folded.

THQ stretches into the new millennium

THQ was riding high into the new millennium. Its wrestling games were body slamming successes, while titles based on other high-profile IPs like the Power Rangers and Rugrats brought the company loads of revenue from the kids market. The company was still churning out its annual slate of mostlyalright licensed games, but their intended audiences kept gobbling them up, and both sides were more or less content. With brands like Disney, Nickelodeon, MTV, Pixar, and Star Wars slapped on their products, at least some money was always guaranteed to roll in.

It was around this time that THQ began to expand its horizons a little bit further. The late 90s and early 00s saw the publisher acquire a variety of existing game companies, most notably Volition, which was then developer of the FreeSpace series and would later head up the Red Faction and Saints Row franchises. It expanded its operations into France and Australia, and even changed its logo into a more forward-looking design (literally). The early bits of the sixth generation of consoles brought a brief dip in profits, but the companys licensed games barrage soon brought it back up to speed.

THQ reaches its highest highs...

THQs dark days were only a few years away by the mid-00s, but before everything exploded, the company managed to reach some relatively great highs. Its strengths by and large remained its WWE and kids games offerings. The company went bonkers with the latter in particular. Games based on Disney, Nickelodeon, and other kiddie franchises were released by the dozens, and stayed big with the young ones into the seventh generation of consoles.

At the time, the lesson was simple: put SpongeBob/any Pixar franchise on a game, [???], and profit. Sure, gamers might look down on tie-ins to kids shows and animated movies, but as long as the dough kept rolling in there was no reason to stop.