"Oh my god, what have I got myself into?" The inside story of the golden age of video game magazines

From Crash, to Zzap!64, and Amiga Power, the anarchic gaming magazines of the 80s and 90s broke the rules and laid the path for the influencers of today

Speaking to games magazine veterans for this feature, one theme comes up again and again – that back in the Eighties and early Nineties, there was a special kind of magic that was bottled by games magazines, the likes of which we’ll never see again. “They have a certain tone and style to them that’s very much of the period,” says Julian ‘Jaz’ Rignall, ex-editor of Zzap!64 and Mean Machines. “I mean, you know, Mean Machines, I don’t think we could get away with saying some of the things that we used to say nowadays.” Matthew Castle, who was Official Nintendo Magazine’s final editor when the publication closed in 2014, says that his biggest regret is that he didn’t get into videogame magazines earlier, during their golden age. “I read a huge pile of old Super Play magazines when I joined Future, and it was just like, ‘Oh, god, this is all so good. Why didn’t I spend my pocket money on this instead of Boglins or whatever it was?’”

Love retro gaming? From SNES to Mega Drive, PSOne to Xbox, and Spectrum to C64, Retro Gamer magazine delivers amazing features and developer interviews about history's best games every month, and you can save up to 57% on a print and digital subscription right now.

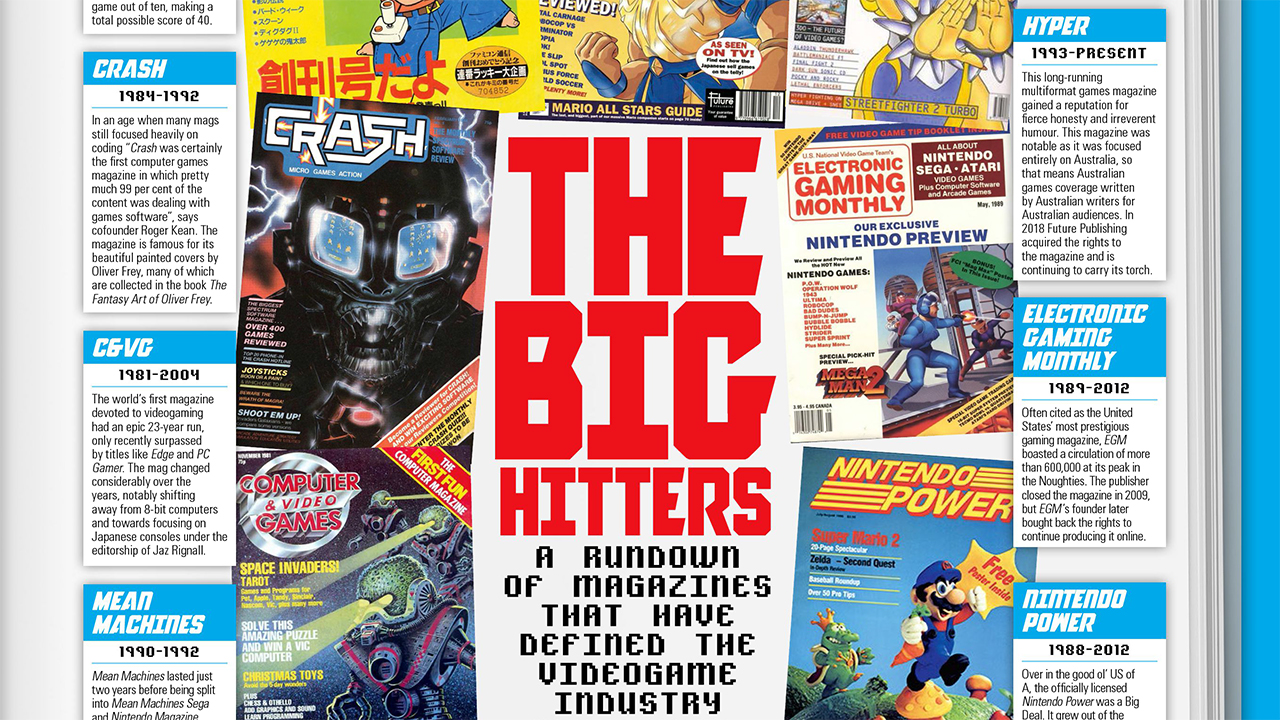

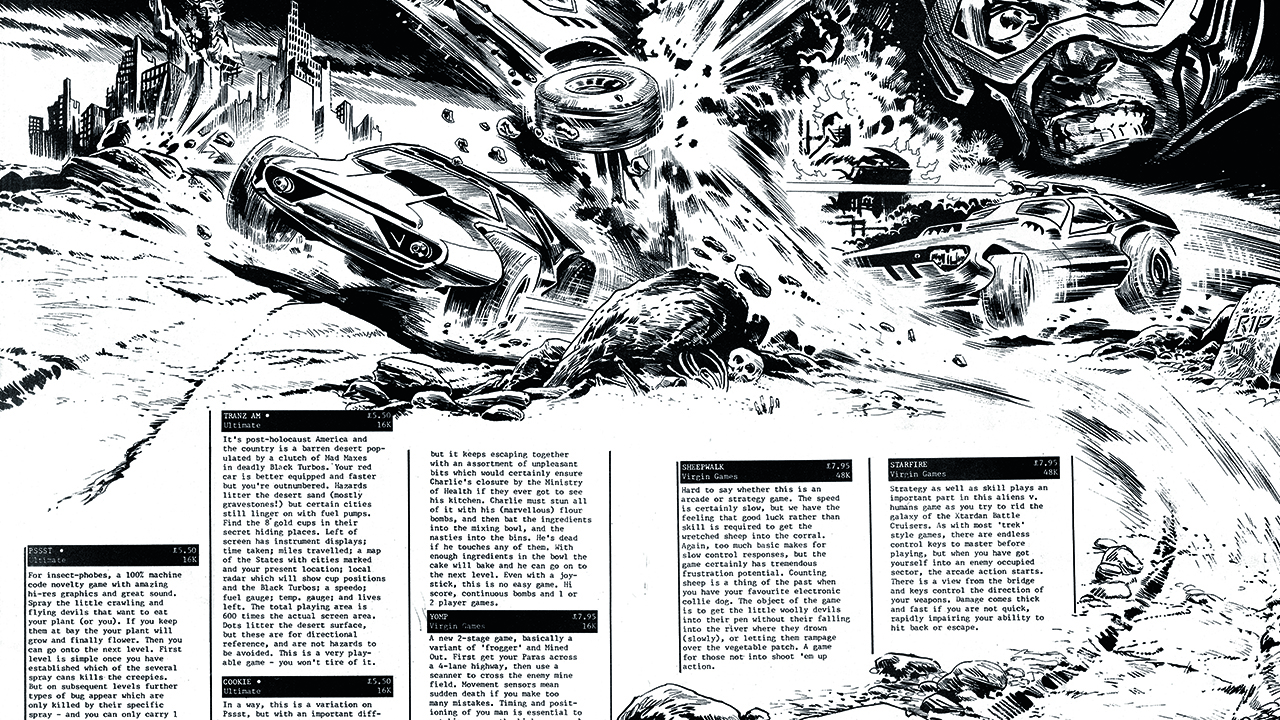

But as the Sega saying goes, to be this good takes ages, and the fusty forerunners of the mighty Eighties game mags were a bit of a dull bunch. Titles from the Seventies like Computing Today and Practical Computing catered to dedicated hobbyists, and were just as likely to feature guides on creating stock-control programs for your small business as games reviews. Then came Computer And Video Games, aka C&VG. Launched in November 1981, it was the world’s first dedicated games magazine, and arguably the ‘proper start’ of gaming magazines as we know them – with not a stock-control program in sight. This was quickly followed by Computer Gaming World later the same year, and then a trickle of magazines dedicated to the various computer formats, like Commodore User (1983) and Your Spectrum (1984), although generally these format-specific titles still had a big focus on the non-gaming side of computers.

Crashing into a new era of games magazines

But in 1984 Crash came along to flip over the publishing industry’s neatly arranged tables and breathe a bit of anarchy into games journalism. Here was a magazine that was unafraid to speak its mind, and give a cheeky wink while doing it. Even the magazine’s name was a wry nod to the ZX Spectrum’s most egregious habit, as well as a reference to a certain controversial JG Ballard novel that Roger Kean, the mag’s cofounder, was a big fan of. And Crash’s approach to reviewing games was revolutionary.

“The people I knew working at C&VG and Sinclair User, they were all in their late twenties, early thirties,” says Roger, “professional journalists who happened to play games and wrote reviews. Whereas what we did with Crash was use the local schoolkids.” Roger created a game review form and handed it out to pupils at the local school along with cassettes of the latest games, then the schoolkids dutifully handed in the completed forms a few days later. Essentially, the games were being reviewed by their target audience, and since these young writers had zero contact with the people who actually made or marketed the games, they had no qualms about being brutally honest. “The thing, of course, about 14-year-olds,” says Roger, “is if they play a game and say it’s crap, it doesn’t matter what I would have said, they’d never have changed [their opinions].”

“I remember we had quite a lot of irate parents after the Dun Darach cover with the guy in chains,”

Roger Kean, Crash magazine

Roger also thinks that Crash was the first magazine to adopt a percentage score for reviews, a format that became widely used across the industry. And most importantly of all, the magazine had a rare sense of humour in the otherwise fairly dry world of computer magazines. “Games were fun, and we were on the whole having fun,” says Roger, which was something that came across loud and clear in the pages of Crash. “I’ve always had a fairly irreverent sense of humour, and I didn’t want the magazine to be, you know, heavy duty.”

Still, Crash’s irreverence occasionally got it into trouble, notably thanks to a couple of artist Oliver Frey’s more racy covers. “I remember we had quite a lot of irate parents after the Dun Darach cover with the guy in chains,” remembers Roger, “but the one that probably got us the most trouble was Barbarian. We did get an official letter from WH Smith saying that they had recommended we be put on the top shelf, and if we did it again, they would deselect the magazine!

Roger says the biggest incident came with issue 19, which carried a feature satirising Sinclair User, or ‘Unclear User’ as they called it. Sinclair User’s publisher, EMAP, took Crash to court, and the latter ended up paying an out-of-court settlement of around £60,000. But Roger says that the surrounding publicity helped Crash to have the last laugh. “We went from about 56,000 copies a month up to over 102,000 over four issues.”

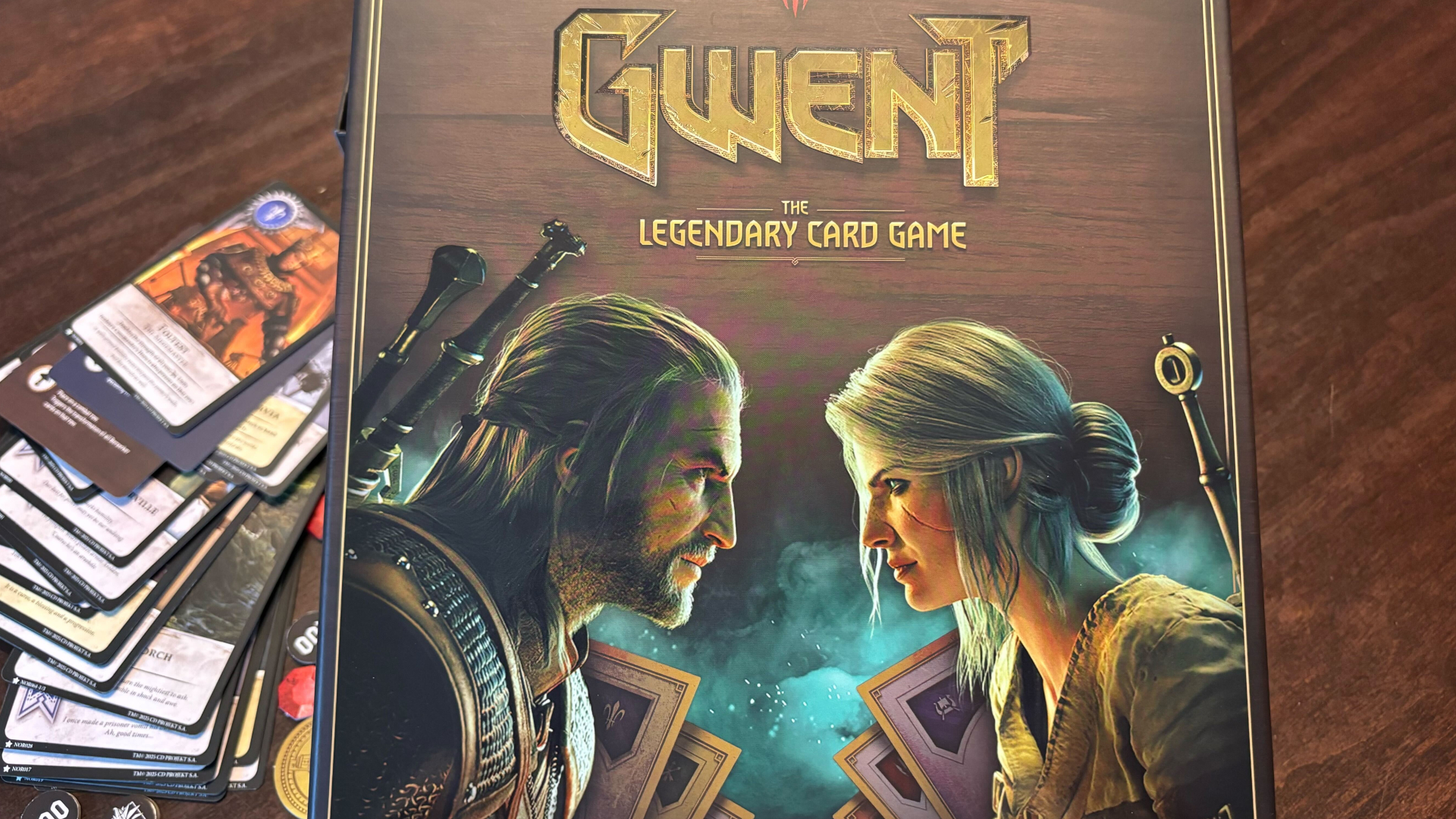

The most influential games magazines

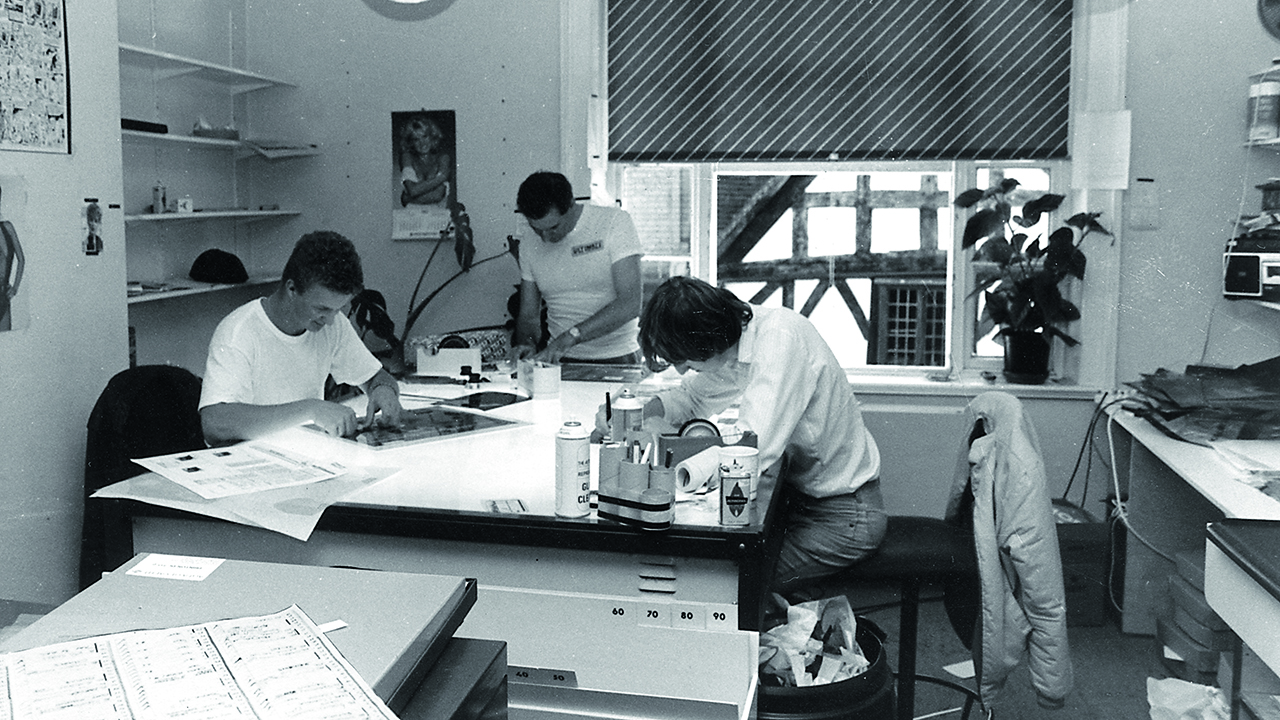

Making magazines with scissors and glue

One thing that has changed massively since the Eighties is the way games magazines are actually made. Back then, cut and paste literally meant cutting some paper and sticking it down to create a layout. “All the layout was physical” recalls Roger Kean, “all paper, scalpels and gum.”

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Still, Roger made sure that Crash and Zzap!64 were kitted out with the latest Apricot computers, which meant that the writers at least had the luxury of being able to send text directly to the typesetters. That meant Jaz Rignall had a rude awakening when he left Zzap!64 to work on C&VG at EMAP in the late Eighties. “At C&VG they were still doing it the old- fashioned way with typewriters. You had to use a typewriter to type up the copy, then the copy would go off to the typesetter, who would copy that document manually, and then you’d have to read the galleys. It was the way things had been done since the Fifties, so it was really old fashioned and clunky.” And getting hold of images in the days before email was often a precarious business, remembers Steve Jarratt: “You couldn’t just grab an image off the internet. I’d be sitting there on Monday morning, going ‘Jesus where’s the post, I’ve got a slide coming from America for my cover image’.”

Screenshots were no walk in the park, either, remembers Jaz. “We did that the old-fashioned way with a camera on a tripod in front of an old CRT that we would clean up so that you wouldn’t get fingerprints on it. In fact, in some of the early issues of Mean Machines, you can see fingerprints where somebody didn’t bother to clean the screen.

“Taking screenshots was a pain in the arse, because you had to hope that the game had a pause mode that didn’t blank out the screen or have a huge ‘pause’ text right across the middle of it. If that happened, then you’d have to stop the game and try to take a picture of it as static as possible. There are some screenshots in C&VG that you can see things are moving and blurred.”

The advent of digital cameras and screen-grabbing software helped to ease the pain of taking screenshots, but even at NGamer in the Noughties, the process was still fraught with problems, recalls Matthew Castle. “We had this capture machine that was big and heavy, and used to get really, really hot, so we had to stick it out of the window to get the air flow through it. So we had this incredibly expensive PC hanging out of the window the whole time, hoping it wasn’t going to smash onto the pavement below.”

Nowadays, anyone can take a pin-perfect screenshot at the touch of a button, but Jaz Rignall reckons that the blurry screenshots in old magazines are actually part of the appeal of these old publications. “There’s something about old-fashioned screenshots taken from a CRT, you know. The phosphorescent, glowing pixels blur together and create a very nice, aesthetic that you don’t get with screen grabs these days.”

A new age of personality journalism

Crash’s Commodore-focused sister magazine, Zzap!64, launched in 1985. Its reviews were written by full-time employees rather than schoolchildren, but, as Jaz notes, they “wanted real gamers that were very good at playing games as reviewers, rather than more traditionally trained journalists”. Jaz himself won the 1983 C&VG Arcade Game Championship. “I played games rather than going to school,” he says.

Like Crash, Zzap!64 oozed personality, partly thanks to the way its journalists ended up becoming celebrities in their own right. “We had our little faces on the reviews, and putting faces on the reviewers was a really big thing back then,” says Jaz. “It really helped establish us as personalities, and that was very different from a lot of magazines that were being written more anonymously.”

And if readers got the impression that writing for a games magazine was some kind of dream job, then they were exactly right, says Jaz. “The office was pretty crazy, you know. We’d write during the day and play during the night, and work and play sort of blended together. We were hardcore gamers, so we couldn’t believe that we were getting the chance to play all this new stuff, and were being paid to write about it.”

Steve Jarratt joined Zzap!64 as a reviewer in 1987, and he recalls his first impression was one of organised chaos. “Everybody seemed to smoke, everybody had got cans or coffee on their desks, there was clutter everywhere... it was literally floor to ceiling shelves of magazines, old Commodore 64 machines, hard drives, joypads and row

upon row upon row of games. It was kind of amazing, but it was also kind of like, ‘Oh my god, what have I got myself into?’”

Jaz left Zzap!64 for C&VG in 1988, partly because he wanted to write about the exciting new Japanese consoles that were emerging at the time. As editor, he steered the magazine away from 8-bit computers and more towards consoles, and in 1990 he convinced the publisher, EMAP, that there was a market for a new magazine focused specifically on these new wonder boxes – what became Mean Machines. But EMAP took some persuading, and accordingly the first few issues were only available in limited numbers. “The first issue, we only made about 27,000 of them, but they sold out completely,” recalls Jaz. “The next issue, we produced a few more and that sold out. And actually that approach was really advantageous to us, because it created extra demand. We had a lot of readers going into the newsagents asking them to reserve a copy because maybe they’d missed out the previous month. Very quickly the magazine grew to be comparable to Computer And Video Games magazine in terms of circulation. It was clear that the player base was very much into consoles and were excited about what was coming out.”

Mean Machines was just as edgy as its title suggested, something that came across most clearly in its infamous letters page. “It was just trying to sort of bounce off the readership and make fun in the right kind of places, not be too cruel,” says Jaz, before adding, “I think occasionally we were a little bit cruel. But, you know, we wanted to have fun and for the magazine to be interactive, and encourage people to write into us. We wanted the magazine to be like a community or a club that you were part of that had its own in-jokes and little insider bits of knowledge.”

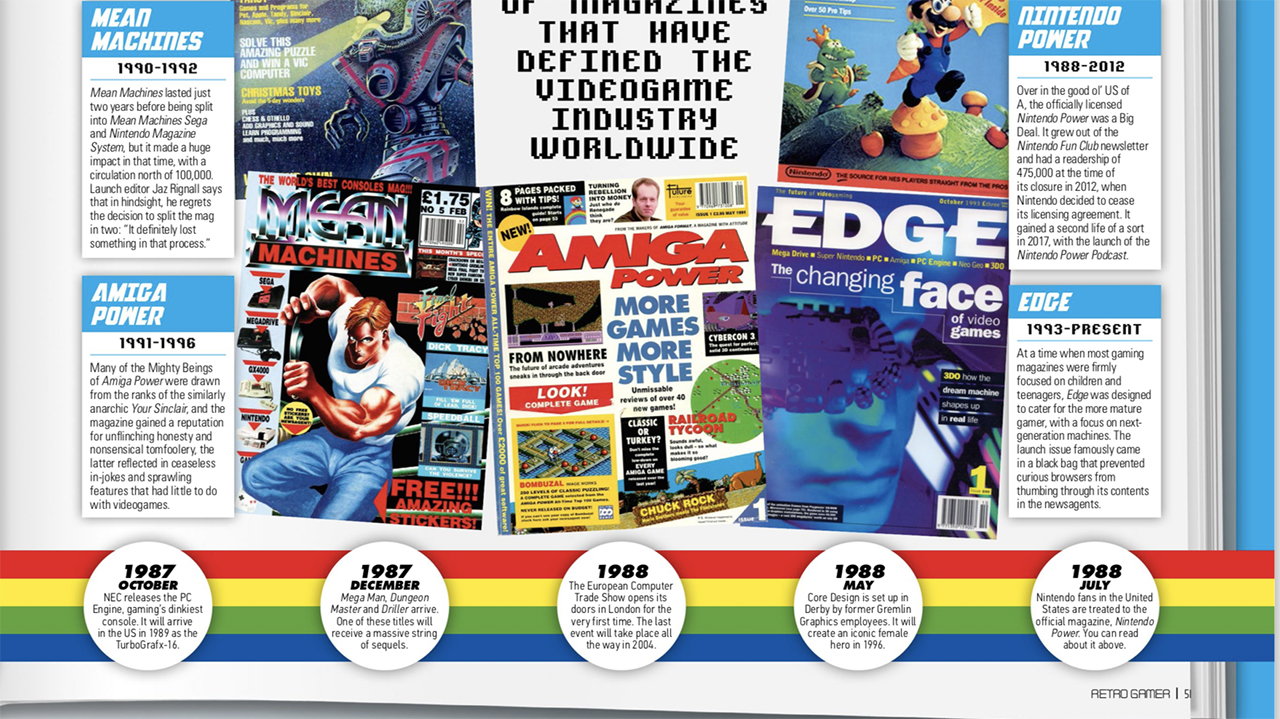

Mean Machines wasn’t the only title to launch in this period: the late Eighties

and early Nineties were something of a boom time for the UK games-magazine industry. Future Publishing put out its first title, Amstrad Action, in 1985, and went on to launch countless others, including the multiformat ACE in 1987. Paragon Publishing started up in 1991, hurling out titles like Sega Pro (1991), Mega Power (1993) and Play (1995), while EMAP launched the well- respected multiformat magazine The One in 1988 and birthed plenty more magazines throughout the Nineties, such as PlayStation Plus (1995) and the ill-fated Maximum (1995). Europress, meanwhile, held its own with publications like Atari ST User (1986) and Amiga Action (1989), and on top of that there were various videogame titles made by Dennis Publishing and Argus. In fact, to give an idea of the sheer volume of gaming publications that were adorning newsagents’ shelves, at one point in the Nineties there were around half a dozen magazines dedicated to the Amiga alone.

Hey Amiga

One of the most notable of those was Amiga Power. Launched in 1991, it became home to many writers who had learnt their craft on the anarchic Your Sinclair, the magazine that evolved from the relatively humdrum Your Spectrum. YS, as it was affectionately known, devoted many of its pages to odd features like ‘Peculiar Pets Corner’, and Amiga Power followed its lead with such joyous nonsense as a massive spread on the assassination of JFK that had absolutely nothing to do with the Amiga, or even videogames in general.

But whereas there was perhaps a surplus of Amiga magazines in the early Nineties, there was also a clear deficit of Nintendo-themed titles – a gap that Future was determined to plug. That hole would be filled with the 1991 launch of Total!, but its genesis was rather unusual, says Steve Jarrat, who was the editor at launch. “They were aware that Nintendo was a bit litigious, so we launched it in secret. [The publishing director] Greg Ingham had a great big loft space, and so we did it up there: nobody else in Future knew we were doing it, nobody in the industry knew about it, it was just me, Andy Dyer and [art editor] Wayne Allen – just the three of us put this issue together.”

Perhaps the loft-bound secrecy was unnecessary in the end, as Nintendo seemed little fazed by Total!’s launch, but Jaz does recall the Big N laying down some strict rules when Mean Machines split into Mean Machines Sega and the officially licensed Nintendo Magazine System in 1992. “Nintendo insisted on having the Nintendo magazine on a different floor to Mean Machines Sega. It was very silly, because we still all went out to lunch together and we still walked up and down the stairs to each other’s offices. Maybe they didn’t want that Mean Machines influence creeping

in too much.”

"Over the next two decades, ‘unofficial’ single-format magazines would be almost completely pushed out of the market."

Officially licenced magazines like Nintendo Magazine System (which went through several name changes before ending up at Future Publishing as the simply named Official Nintendo Magazine) gained prominence throughout the Nineties and beyond. Interestingly, several publishers had concurrent ‘official’ and ‘unofficial’ magazines covering the same format, like Sega Magazine (1994) and Mean Machines Sega at EMAP, Xbox World (2003) and Official Xbox Magazine (2001) at Future, and PSM2 (2000) and Official UK PlayStation 2 Magazine (2000), also at Future. The latter’s original incarnation in particular – Official UK PlayStation Magazine (1995) – was a massive success for the publisher, with its phenomenal sales probably having a lot to do with the generous demo disc that straddled the cover each month.

Gradually, over the next two decades, ‘unofficial’ single-format magazines would

be almost completely pushed out of the market. Matthew Castle saw both sides of the divide as editor of the unofficial NGamer (which evolved, via several name changes, from 1992’s Super Play) and later on as editor of Official Nintendo Magazine. But when

NGamer closed down in 2012, he was initially reticent about sailing into officially sanctioned waters. “In my head, you know, I was ‘unofficial Nintendo mag for life’. We were the same company, but they were our rivals. I didn’t really want to be part of it, I didn’t necessarily think their world view matched up with ours – but I wanted a job.”

Still, he says that although the Nintendo licence meant he was more constrained

in what he could do at Official Nintendo Magazine, the lean Wii U years were actually somewhat of a blessing in disguise, freeing the writers to fill pages upon pages with gloriously nonsensical features thanks to the lack of new games to write about. In a way, the anarchic spirit of magazines like YS and Amiga Power flared again for an instant. “I think the last year or so of ONM is actually pretty strong,” says Matthew. “There was some stuff where I was like, ‘There’s no way Nintendo is reading this magazine anymore.’ There were bizarre alternative Christmas carols that were making fun of the then head of Nintendo Europe and stuff like that. There were several things we printed where I then had nightmares I was going to get fired. We did come close on a couple of occasions: I made a joke about McDonald’s, which almost got me nuked because they had a Happy Meal deal with McDonald’s.”

And so we come to the present. The past decade and a bit has seen even the most mighty magazines fall as they struggled to compete with the migration of readers online. C&VG closed its print version in 2004, living a half-life as an online-only publication until 2014. Official Nintendo Magazine bowed out in 2014 after Nintendo withdrew from print magazines. Play ended its print run in 2016. GamesMaster survived long after its namesake TV show was put out to pasture, but it eventually succumbed to the inevitable in 2018, after 25 years of publication. The multiformat gamesTM from Imagine Publishing, former home of Retro Gamer itself, went silent at around the same time, after 16 years on sale.

But there are still a few holdouts. The official Xbox and PlayStation magazines

still carve out a space in WH Smith, and PC Gamer has been continually published since 1993. Last year even saw the launch of a brand-new games magazine in the form of the indie-centric Wireframe, while pre-teen-focused mags like 110% Gaming thrive on newsagents’ bottom shelves. And then there’s Edge, which earlier this year celebrated becoming the United Kingdom’s longest-running games magazine. Long may they all continue!

This feature is taken from Retro Gamer Magazine and you can save up to 57% on a print and digital subscription by subscribing today

Lewis Packwood loves video games. He loves video games so much he has dedicated a lot of his life to writing about them, for publications like GamesRadar+, PC Gamer, Kotaku UK, Retro Gamer, Edge magazine, and others. He does have other interests too though, such as covering technology and film, and he still finds the time to copy-edit science journals and books. And host podcasts… Listen, Lewis is one busy freelance journalist!