GamesRadar+ Verdict

Pentiment tells a tale that enthralls at the level of the personal and social alike, exploring a history that doesn't merely recreate period objects and customs, but functions as an evolving process sculpted by individuals within circumstances beyond their control. A melting pot of ideas and characters adds nuance to tightly plotted murder investigations, as does an art and scripting style inspired by 16th century scribes. The pace may feel slow at times, but for all the focus on dialogue choices, Pentiment is anything but all talk.

Pros

- +

Dialogue choices loaded with significance

- +

Incredible historical detail and nuanced treatment of events

- +

Neatly plotted murders and compelling investigations

Cons

- -

The plot drags its feet occasionally

Why you can trust GamesRadar+

Lodging in the Gertner's guest room in Pentiment isn't exactly a life of luxury, but it's comfortable enough. Except that is for the pangs of guilt. It's only when you return to the farmhouse at night that you realize what it means to be renting out the upper floor – five Gertners are crammed into a pair of single beds downstairs, including the formidable Big Jorg, with the elderly sixth scrunched up in a wooden chair by the hearth. Yes, you're paying rent, and they don't complain about the arrangement, but you can't help viewing your presence as a terrible imposition.

Release date: November 15, 2022

Platform(s): PC, Xbox Series X, Xbox One

Developer: Obsidian Entertainment

Publisher: Xbox Game Studios

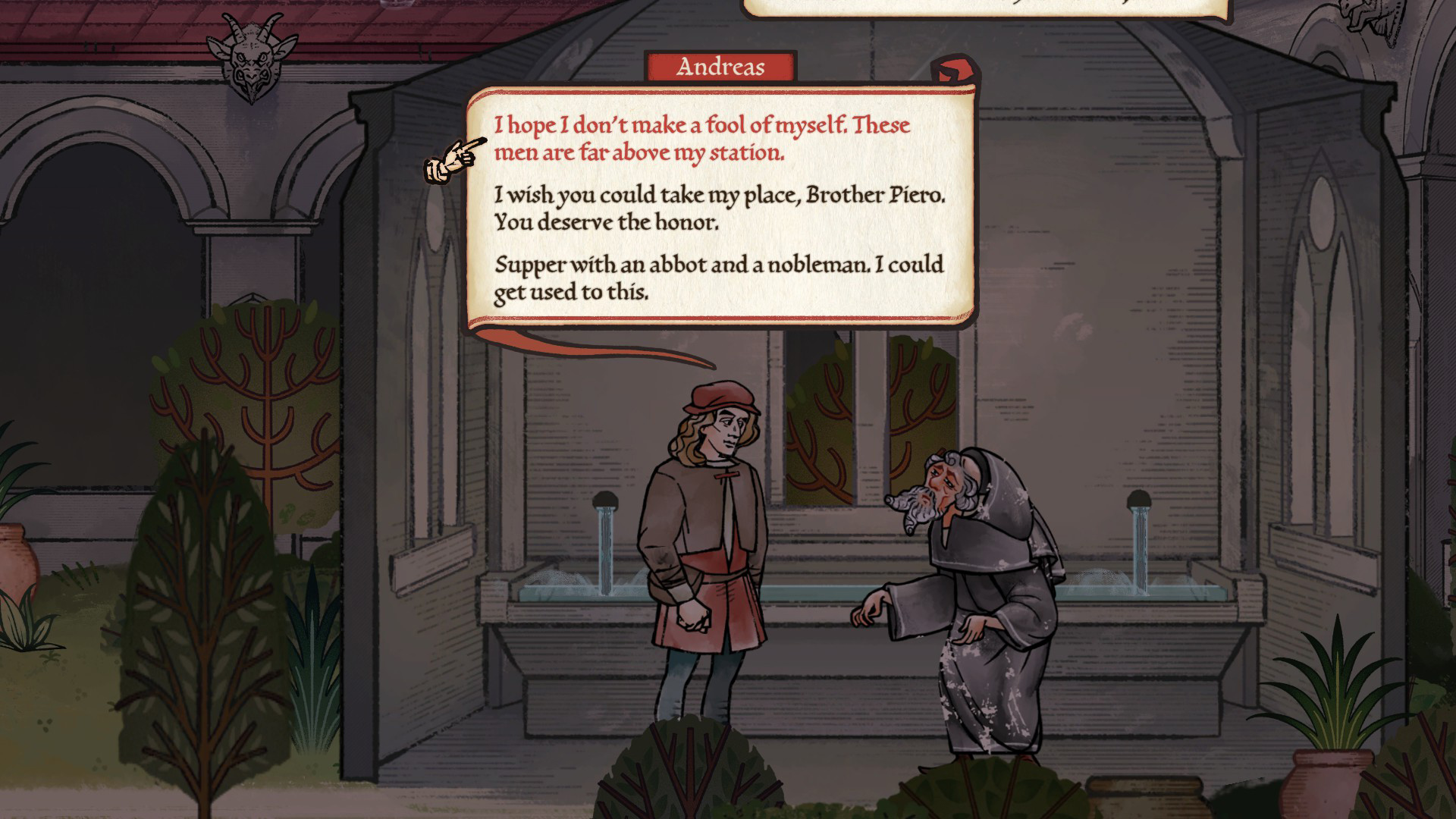

There's no escaping such awkwardness, though. As Andreas Maler, an educated artist, you'll always be a level above the Gertners, literally and figuratively, whether you like it or not. This is 16th century Bavaria, and while there's social change afoot, thanks to the proliferation of the printing press and rumblings of church reformation, most people's lot in life is determined at birth. That doesn't mean everyone is happy with the status quo, of course, even in a remote alpine town like Tassing, but it does mean that in a game largely about dialogue choices, every conversation is saturated by presumptions of status and superiority.

And Pentiment is a game largely about dialogue choices – akin to the part in an RPG where you arrive in a new town, talk to the residents and rifle through their belongings, but expanded and zoomed in to sharp focus until every NPC becomes all too human. There's even a little RPG-style character customisation to kick things off, where you select what Andreas studied at university, his interests, and the languages and customs he's absorbed on his travels.

With the understanding that Andreas is going to be embroiled in a murder investigation, perhaps you decide it would be prudent to have a background in Latin, or in medicine. Perhaps you want an Andreas whose youth was spent with his nose in books, or you'd prefer a party animal who mostly had his nose in a glass of wine. All choices are useful in their own way, adding extra dialogue options that affect how you relate to clues and people.

Speech to text

With those decisions out of the way, you get stuck into a daily routine, and the experience of Pentiment is like scampering around inside a 16th century comic book, illustrated with great care by the artists of the day. It's also a bit like taking part in a theatrical performance, thanks to the fixed sets comprising the town and its nearby abbey, and the expressive animations of the flat-sketched cast as they deliver their parts in a splendid script. Most of all though, once you dig into the substance of it, Pentiment feels like an Umberto Eco novel drawn to life – with all the historical detail, myth, and mystery you'd find in works such as 'The Name of the Rose' or 'Baudolino'.

Like those books, Pentiment entwines its murder plot with debates on the philosophy of the day, clashes between church doctrine and 'heretical' theories, and the value of art, literature, and folk tradition in comprehending our present and past. In a story focused on three events spread across 25 years, the dawning of a new age is palpable, and the struggle to come to terms with it rumbles furiously throughout, whether from monks still painstakingly scribing tomes, elder villagers clinging to pagan rituals, wives desperate to alter inheritance laws, or young firebrands who've learned to read and question authority. Murder is merely one ingredient in a rib-sticking stew of ideas that colours your every question, suspicion and judgement.

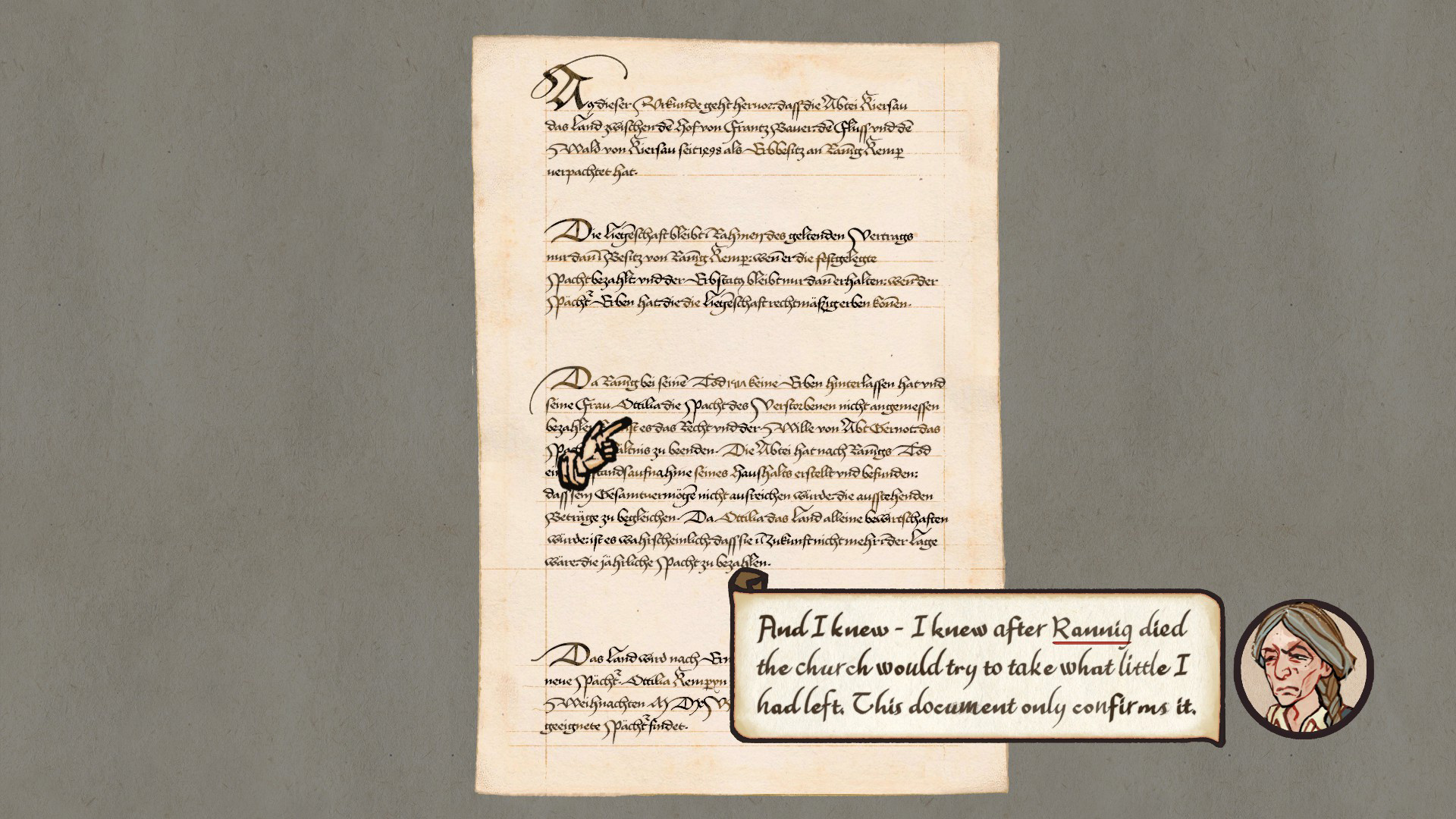

It's not only what people say that matters in this tale, though, but the way it's written. Pentiment assigns different fonts to different characters to great effect, with speech bubbles telling you something about Andreas' perception of an individual as soon as they open their mouth. Peasants talk in rough joined-up writing, while the words of monks appear as fine calligraphy (there's an option for more standard text should you need it), and the town printer deploys a clinical typeface. Each form is obviously a marker of dialect and education, but you also note how some people make spelling mistakes as their responses scribble onto the screen, or leave the page flecked with ink spots in particularly emotional exchanges. These blemishes ensure that the activity of reading itself becomes part of the narrative texture.

Mind your language

In this way, Pentiment asks you to read between the lines of conversations, to contemplate intent and the social circumstances from which speakers emerge, which in turn complicates your role as protagonist. As an artist commissioned by the abbey to illustrate their books, Andreas is an outsider, which means he possesses a level of freedom that neither the monks nor the townsfolk enjoy. But while, as in some of the best mystery games like Paradise Killer or Return of the Obra Dinn, that freedom grants him autonomy to investigate, with more access to people and places than most, it can also be a source of resentment for potential witnesses and suspects.

You can't then simply rely on knowledge or reasoning to get your way. It's not always a smart move to demonstrate your expertise of Latin or the law, for instance, because you may come across as a know-it-all or a show-off. Nor should you necessarily articulate sympathy for the plights of the less fortunate, lest you seem patronizing or reckless. Especially in Pentiment's second act, when the peasants consider revolt against the abbot's suffocating taxes, while it may be morally right to spur them towards uprising, it's not your life on the line. As one monk explains, "It's easy enough for you to come and go. You don't have to live with the consequences." Precisely because of your education and privilege, sometimes it's best to shut up and listen.

This need to be mindful of what you say is underlined on occasions when one of your responses triggers a message on screen: 'This will be remembered.' You can't be sure when this is going to happen – although it's generally a safe bet if someone is directly asking for advice – and sometimes idle banter might be taken quite seriously, so you can't drop your guard. Remembered decisions then come to a head sooner or later, perhaps when you need some help from a character, and they tot up their pleasure or distaste at your remarks, in some cases with access to important information on the line.

"Precisely because of your education and privilege, sometimes it's best to shut up and listen."

Such information may then be a matter of life or death when it comes to pointing the finger at a murder suspect. In the game's first two acts (I'll keep quiet about the third), you don't merely follow linear clues to unveil a clear culprit. Instead, you find evidence that directs suspicion at three or four individuals, but no smoking-gun proof, then deliver a testimony that will effectively condemn one to death. In the first act, your friend and mentor, an elderly monk and calligrapher, is caught with a bloody knife in hand; convinced of his innocence, you have until the archdeacon arrives in town to find a plausible alternative suspect. But limited time means you can't follow every lead, and must ultimately deliver an educated guess or, if you prefer, accuse whichever of the potential killers you think most deserves to lose their head.

However you approach the case, you'll have plenty to mull over, thanks to a classic whodunnit setup that throws shade on the pious and unwashed alike. In the opening scenes of act one, before the crime has occurred, you encounter a nun who has prophesies of death, an unruly local thief who will flee the village after the attack, a shifty prior, an old widow who curses the baron's arrival, and a stonemason with an axe to grind. Unlike the average Poirot mystery, however, your attempts at playing detective can feel arrogant and misguided. After all, you're rushing to judgment over people who may be ill-equipped to defend themselves, and your intervention could disrupt the futures of whole families, or the abbey itself.

Slow your roll

The big decisions only become harder in the second act, when Andreas returns to Tassing, renews acquaintances and wades deeper into the local culture. As you find out what happened to the folks you met before, Pentiment lingers on the minutiae of their lives, and you become more attached to their fates. Many developments are outside of your control, determined by the wider plot, yet rarely in games does the passage of time feel so intimately significant.

No doubt, the depth of historical research on show here and quality of writing are key contributors to your emotional investment, but equally Pentiment succeeds in this respect because it's a deliberately slow experience, matching its loop to rhythms of existence where farmers obey the demands of the seasons, letters take weeks to be delivered, and monks wracked with arthritis spend decades duplicating books by hand. The day-night cycle – divided into phases for work, meals, and sleep – rolls steadily but ponderously, as if in stark contrast to the rapid fire pace of a Persona game calendar.

Meal times are crucial in this respect – a chance to sit with a family of your choosing and perhaps discuss developments in your case, or simply your host's daily grind. Some homes offer little more than bread and cheese, while others serve salmon and roast beef, or medieval dishes such as 'frumenty' that send you rushing to Google. But regardless, you don't eat merely to fill your stomach, you do it to get to know people, and maybe learn a thing or two. When you might otherwise sprint from objective to objective, this is a chance to take stock, and give the town's situation the consideration it deserves.

"Many developments are outside of your control, yet rarely in games does the passage of time feel so intimately significant."

There are times when Pentiment crawls a little too slowly, particularly in a third act which jettisons the compact timeframe of its predecessors. Yet there are intriguing new themes still being introduced even then, celebrations and customs to enjoy, and conspiracies left to unearth (leading to an ending that's almost worthy of Eco himself). Tasked with deciding how the history of the town will be recorded, and especially a terrible event that's scarred the community, it's up to you to ponder truth and reconciliation, consider what it means to progress, and whether disaster can lead to better lives in the long run.

By now you know the townspeople better than you'll ever know most game characters. You're party to loves, losses, disputes, friendships, gossip, redemptions, and damnations. It warms the heart to see a fledgling courtship blossom into a blissful match, and stings when you learn that there's little food to go around at the Gertners' place these days. You might then stop to consider your role in these fortunes, powered by strength of the written and spoken word. If so, you may surmise that Pentiment isn't merely a historical story but a reminder in an age of social media and instant reply that language is something to be chewed, digested, and directed with care. Knowing when to speak, how to speak, and what to say has never mattered so much.

Pentiment was reviewed on PC, with a code provided by the publisher.

More info

| Genre | Adventure |

Jon Bailes is a freelance games critic, author and social theorist. After completing a PhD in European Studies, he first wrote about games in his book Ideology and the Virtual City, and has since gone on to write features, reviews, and analysis for Edge, Washington Post, Wired, The Guardian, and many other publications. His gaming tastes were forged by old arcade games such as R-Type and classic JRPGs like Phantasy Star. These days he’s especially interested in games that tell stories in interesting ways, from Dark Souls to Celeste, or anything that offers something a little different.