Pixels to polygons: How 2D games tried to shine in a 3D world

Retro Gamer speaks with veteran developers to explore the transition from 2D to 3D

Take a dive through the video game media in the mid-Nineties and a theme quickly emerges: the future is 3D, and that future is now. The history of 3D technology can be traced back to 1974, first appearing in games like Maze War and Spasim, followed by the tank simulator Battlezone, rear cameras in racing games like Pole Position, and taking shape in first-person shooter games like Wolfenstein 3D. But a substantial wave of 3D games arrived with the fifth-generation consoles in the mid-Nineties, as the Sony PlayStation, Sega Saturn, and Nintendo 64 set out to change the market. Why would anyone want to take a step back from the cutting edge?

An opinion piece published on TechRadar in 2010 said, “Going back to an early Nineties 3D game now is almost painful. Flat faces, non-moving lips during conversations, stick-figure character models, smeary textures, and appalling animation... the list of problems goes on.” But not every title fell victim to forced polygons and age. The visuals and controls in the legendary Tomb Raider haven’t aged well, and Super Mario 64, one of the first successful 3D platformers, puts more work on players to control a flawed camera system so Mario and the environmental perils can remain visible. That didn’t take away from the sensory intimacy of the game. Ed Annunziata, creator of Ecco The Dolphin and Mr Bones told us, “The world changed when I played Super Mario 64. Specifically, the moment where I wondered, ‘Can I jump in the water?’ Then I tried it and when my Mario splashed into that beautiful clear water, my brain tasted pool chlorine for a moment.”

"Underrated style"

For more in-depth features exploring classic games and consoles delivered right to your door or device, subscribe to Retro Gamer today in print or digital.

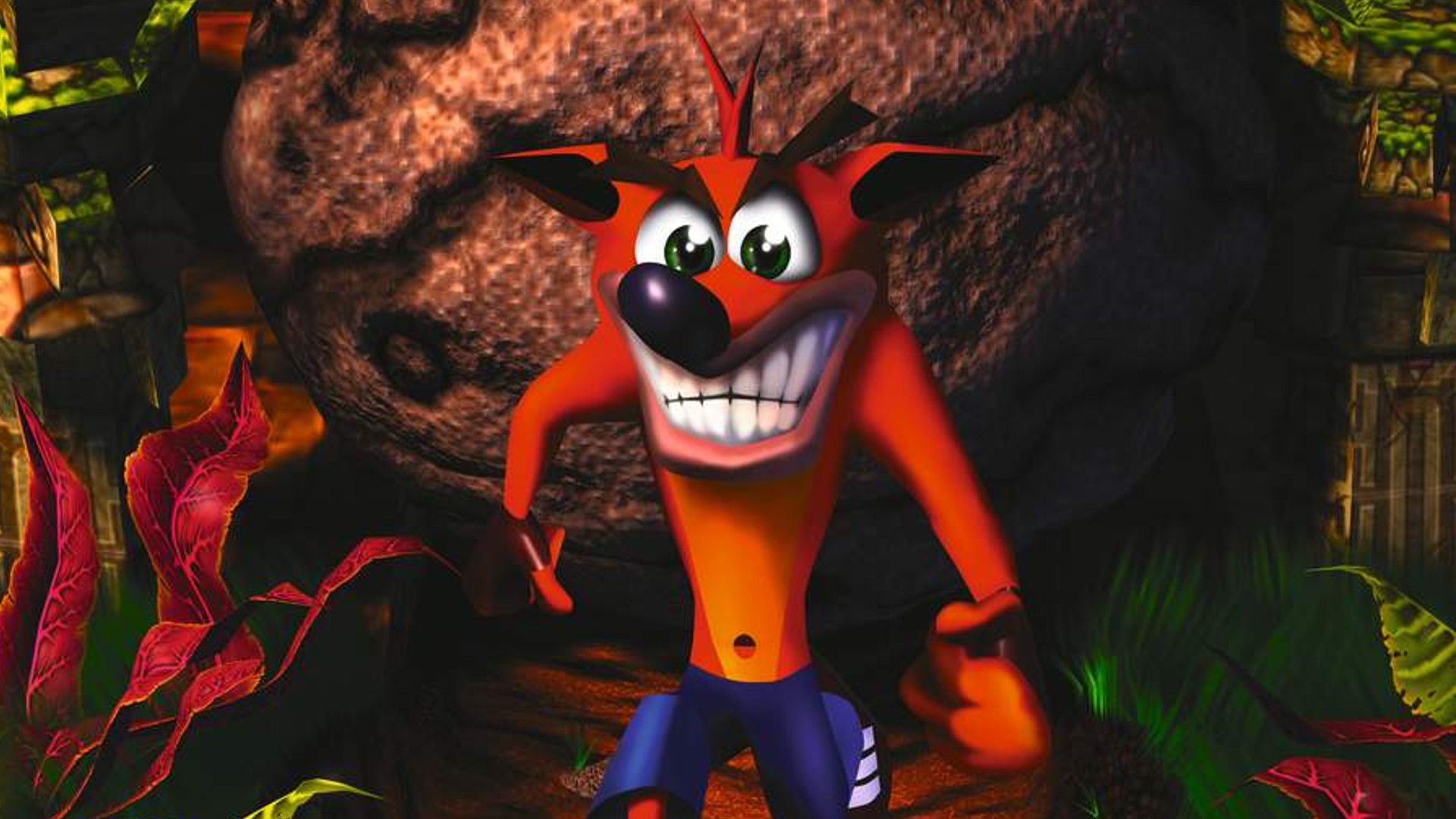

Many games succeeded solely on an experience that couldn’t be replicated on any other home console, and the third dimension played a big role in that. Braving a new frontier in gaming is never easy. Andy Gavin, cofounder of Naughty Dog and lead programmer on Crash Bandicoot, said recently in an interview that he had to hack the PlayStation hardware to make the 3D work the way they wanted, as it almost pushed the systems too much.

“The problem has always been the same,” according to PC Plus via TechRadar, “the potential of 3D fights with the limitations of current systems, whether it’s simply displaying the graphics in the first place or making them look as good as other art styles,” Gavin said. But many of those supposed early 3D ‘classics’ don’t quite hold up in functionality or appearance, while the alternative 2D offerings retain their charm. Games like Street Fighter III: 3rd Strike, Mega Man X4, and Castlevania: Symphony Of The Night are all still easy to play today and are continuously being ported.

While some creators abandoned the two-dimensional plane when 3D became possible, others in the industry felt there was no need to deem the old style obsolete. “Ever notice that 2D games that fake 3D often look cooler than real 3D?” Annunziata asked us, “That’s because the 3D effect is artistically or cleverly crafted.” Many creators saw the almost abandonment of the two-dimensional style as unfortunate. Many felt that games still using the two-dimensional plane enhanced their overall presentations with more elaborate, detailed pictures, so why rush to leave that perspective behind?

Game developer Soren Johnson, who worked on Spore, Civilization IV, and Dragon Age Legends, formerly of EA, spoke in an interview originally for Game Developer Magazine about the genuine choice developers have between 2D and 3D, arguing that 2D games are, "An underrated style that is often unfairly ignored as an old technology.” Developers ultimately believe that games with excellent 2D graphics age more gracefully.

Possibilities

"Yes, we did go to the zoo and observe the gorillas": The making of Donkey Kong Country

Josh Tsui, a game designer and artist, formerly of Midway and EA, believes many 2D games made in the early 3D era held their weight. “3D was too young at the time and a lot of those games look terrible now while the 2D stuff looks better,” he tells us. “It’s a bit unfair to compare though as you’re comparing late-stage 2D against early stage 3D.” Technology’s strengths and limitations played a big role in a game’s presentation. “Look at Wrestlemania [the arcade game], those are still some of the best sprite work of any game out there, even to this day,” Tsui says. 3D lent itself better to backgrounds, while character models were more of a challenge. “The artwork was crafted specifically for those machines and we were able to make them sing.”

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

This didn’t mean that every game left in the former dimension looked better. “I think having fantastic art direction on 2D games really stood them out,” Tsui continues. “Look at the first three Mortal Kombat games. The artwork is still amazing and rich. This was due to the amazing art direction.” So why leave behind refined hardware to risk the untested waters? For Tsui, with the passage of time, these transitions are always an inevitability, “It was just the natural evolution of the technology. By the time the Nineties came around 2D basically had the ceiling.” Annunziata agrees. “Everyone felt the same way, 3D was the future.” Like many in the profession, Jenna Fearon, an artist and game developer, saw the vast opportunity, “For us, at Tiburon, we were all totally wowed by what could now be done.”

But it wasn’t just developers that were awed by the possibilities, as Chris Sutherland, the head programmer on Donkey Kong Country who still makes 2D games like the recent Yooka-Laylee And The Impossible Lair, remembers. “Fifth-generation consoles such as the PlayStation and N64 allowed games to display visuals that the mass market of console owners had never experienced; both that and the accompanying platform marketing made it clear that 3D games were the ‘new cool thing.’”

Prioritising technological innovation over a game’s potential for longevity, as many developers at the time did, doesn’t always serve the game’s artistry. Greg Sewart, alumni of Electronic Gaming Monthly, tells us, “There are plenty of developer interviews where folks who were in the industry back then lament the switch. Especially from a visual standpoint. Since 3D games on the PlayStation, Saturn, and N64 really didn’t look very good even at the time, where the late games on the SNES/Genesis could be absolutely gorgeous looking.”

One late SNES game that bridged the gap was Donkey Kong Country, which was able to ride the trend for 3D visuals despite being on a console primarily designed for 2D gameplay, as Sutherland recalls. “If the world wants 3D and you are making 2D, well you can always try and fake it! There are techniques such as layering the 2D visuals to give a 3D parallax effect and also one can pre-render the 2D animation frames both for extra detail and smoothness. Even today, games like Clash Of Clans do this on mobile.”

Attendees of the 1994 Consumer Electronics Show were sufficiently impressed by the game’s pre-rendered 3D graphics that they believed it was for the successor to the SNES, and they were of a considerably higher quality than the real-time 3D on the new consoles. “Tim Stamper [of Rare] said that he wanted [Donkey Kong Country] to be a game people would still be impressed with when played in many years to come, and he was correct,” Sutherland remembers.

2D to 3D

For Annunziata, frustrations with the new machines included how inefficient they were at representing 3D imagery. “Like the Saturn,” he admits, “I think every single 3D game on that platform looks like crap, including mine.” His displeasure even extended to his character, Mr Bones. “I wish Mr Bones was pre-rendered. We wanted him to be 3D and driven by motion capture so bad we ended up making him look terrible. The motion is ahead of its time in my opinion, but his parts are so aliased we should have called him Mr Static.”

According to Sutherland, creators faced many difficulties making these new larger games. “There was extra complexity and problems that appeared when creating 3D games, and at that time there weren’t that many 3D titles to be able to see how others tackled it.” Companies had to consider how developers would work with this new and issue-riddled hardware to create games as well. “There was, of course, a whole slew of know-it-all people who felt that devs that made 2D games couldn’t make the transition to 3D,” Annunziata continues. “I remember the phrase, ‘They don’t know 3D,’ as if it’s inaccessible knowledge only the very few could obtain.”

Many could learn, but Sutherland remarked that some in the industry just didn’t have the skill sets to evolve to a new way of doing things. “Moving from 2D to 3D is quite a leap for artists and engineers, in some cases, it involves hiring new staff with the appropriate skills so these changes can take time.” Sewart also confirms this, “They were relearning almost everything from scratch.” Many were up for the new challenge, excited by its newness, and these programmers and engineers would thrive best with 3D, “Since almost all of the long-established game development and user experience rules didn’t really apply anymore,” Sewart continues. Games couldn’t stay in development forever, but this new education took time and trial and error. Of course, not every company was led by the technology of the home market, and Midway’s own technological investments ultimately dictated the pace at which it embraced 3D.

“The main decision for most of these games was that (except for Mortal Kombat Mythologies) they were arcade games. Arcade machines from Midway at the time were 2D systems. So we really pushed the boundaries of the hardware,” Tsui explains. But 3D games were also taking over the arcades and the success of the consoles was impossible to ignore, so the switch was inevitable. Even so, Midway’s first steps were tentative. “Mortal Kombat Mythologies was different, that was a combination of 2D and 3D and really acted as a bridge for Midway to transition their games to the new tech,” Tsui recalls. “The characters were all in 2D because 3D characters were terrible at the time. But 3D was great for environments so we wanted to play to each tech’s strengths. The game is so-so but I feel like we really pulled that combo off (pun intended!).”

"New wave"

Crash Bandicoot turns 25 – How Naughty Dog transformed Willie the Wombat into a PlayStation icon

The new push to 3D drove some to see the old style as ‘unfashionable’. “The platform holders needed to drive sales of their new consoles and one way they could do this was to focus on game titles that clearly could not have been created on previous systems,” Sutherland mentions, offering insight from higher-ups. “There was a feeling that 2D was like silent movies in the age of unsilent films,” Annunziata bluntly tells us. “It felt like when you pitched the idea for funding, you really, really, wanted to say this game is 'Three Deeeee!’”

This wasn’t just on the industry side, however. “I think the anti-2D stance, for the most part, was at a publisher level,” Annunziata says. “There were players who had strong preferences either way, but the focus on 3D games really had more to do with decisions made by those who were footing the development bills and taking on the financial risk.” One, in particular, stood out to him. “Sony had a pretty open, anti-2D stance, and considering the PlayStation basically took over the world, pickings were pretty slim for a while there.”

That isn’t to say everyone felt that 2D was being pushed out, or that they agreed with these unflattering sentiments. “Not so much unfashionable, just business,” says Fearon, “The industry was going 3D and we followed. There were still 2D games being made, but 3D was the new wave.” However, she admits it affected the team as a whole. “A few of us artists were still interested in doing some 2D games (I was one of them) and John Schappert, our boss, let us spend some time developing ideas, but ultimately the industry (and particularly EA) was interested in moving into 3D.”

Even if some developers wanted to still play in the old world, larger company mandates prevented that. “Developing a game was a larger financial risk in the late-Nineties than it had been even three years earlier,” Sewart explains. “Plus I think a lot of folks lost a lot of money on the whole FMV games push a few years earlier, so the safe bet was probably the way to go.”

Looking back

Nostalgia factored into some fans pushing the move into the three-dimensional gaming realm. “The excitement of classic franchises entering the third dimension got a lot of people wearing rose-coloured glasses at the time,” Sewart mentions. “Castlevania 64 being a great example. That game was always pretty clunky, but still got very good reviews back in the day.” The desire to see beloved characters rebooted with new, more elaborate adventures left little room for anything that didn’t scream ‘new technology’, even for 2D games that still utilised some advancements. “I think a lot of people didn’t really know the difference between 2D and 3D since it was all just flat graphics on a TV screen,” says Fearon.

Whether consumers knew how the tech worked or just wanted what was ‘cool’, the affinity for 3D games has shifted, over time. “People are starting to look back at some of these games and revisit how good they were,” Tsui explains. “Some games were just better in 2D and made sense to stay that way. A lot of games went 3D for no reason other than to try something new without realising how gameplay can sometimes get compromised.”

Creators who stayed with what they knew did so not because they couldn’t make the transition, but because they felt 2D worked better. “One of the first interviews I ever did with a developer,” Sewart recalls, “was Lorne Lanning and Sherry McKenna talking about their first game, [Oddworld:] Abe’s Oddysee. They were a company that cared more about its artistic vision than the latest tech, and so they made the choice to stick to 2D rather than compromise the visual fidelity of their world and characters.” Sewart also points out it was sometimes exciting to see a new 2D game because they were few and far between and, “There was never any danger of a 3D games shortage.”

Many interviewed here believed it wasn’t necessarily easier to make a 3D game over something in 2D or vice versa. “Easier simply comes from the amount of effort you decided to put in a game,” Annunziata says. “All games are easy to make if you don’t want to spend a lot of time on it.” The early 3D era pushed the industry forward, but for Tsui and others, looking back at games that took advantage of the hard work in 2D that preceded them was like ‘watching paintings come to life’ in an otherwise blocky and triangle-filled polygonal world.

This feature first appeared in issue 224 of Retro Gamer magazine. For more great in-depth looks classic games, you can pick up a single issue or subscribe at Magazines Direct.

Retro Gamer is the world's biggest - and longest-running - magazine dedicated to classic games, from ZX Spectrum, to NES and PlayStation. Relaunched in 2005, Retro Gamer has become respected within the industry as the authoritative word on classic gaming, thanks to its passionate and knowledgeable writers, with in-depth interviews of numerous acclaimed veterans, including Shigeru Miyamoto, Yu Suzuki, Peter Molyneux and Trip Hawkins.