20 Years of the Nintendo DS: "If someone had told you in 2004 that Nintendo was about to abandon the Game Boy, would you have believed them?"

Game developers and media reflect on the hugely successful launch and mass appeal of the Nintendo DS, celebrating 20 years of the twin-screen handheld

We're going to pose a question to you all, and we want you to answer it honestly. If someone had told you in 2004 that Nintendo was about to abandon the Game Boy, would you have believed them? While each of Nintendo's home consoles to that point had sold less than its predecessor, the Game Boy family of consoles had been the company's golden goose, a reliable set of earners and a brand that had become synonymous with handheld gaming as a whole over its 15-year history. So of course Nintendo wouldn't do that, it would be a ludicrous thing to do. However, history tells us that while it took a while, that's exactly what Nintendo did – and it was all thanks to the Nintendo DS.

The Nintendo DS was first announced in a press statement in January 2004, with Nintendo's president Satoru Iwata stating, "We have developed Nintendo DS based upon a completely different concept from existing game devices in order to provide players with a unique entertainment experience for the 21st century." Nintendo revealed that the console would have two three-inch screens and two processors, with GamesIndustry.biz noting in some reports that the screens would be backlit and the processors would be an ARM9 and an ARM7 – all of which turned out to be accurate. Nintendo teased that the initial announcement was "but a glimpse of the additional features and benefits" that would be revealed in full at E3 that year, and that the system would be marketed separately to the GameCube and Game Boy Advance.

This feature originally appeared in Retro Gamer magazine. For more in-depth features and interviews on classic games delivered to your door or digital device, subscribe to Retro Gamer or buy an issue!

When Reggie Fils-Aime pulled out the DS during Nintendo's E3 presentation in Los Angeles, he dubbed it the "developer's system" and said, "In creating DS, we've given the world's most talented game makers new tools to work with, new ways to express their imaginations and of course, in the end, new enjoyment for all of us. DS not only changes Nintendo, it changes our industry." The system boasted full 3D graphics, the lower display functioned as a touch-screen, and there was a microphone too. A variety of games and tech demos were shown, with a handheld version of Super Mario 64 doing the most to turn heads. Reactions to the new machine were mixed. While the DS was undoubtedly a step up from the Game Boy Advance, it wasn't a graphical match for Sony's PlayStation Portable and some worried that Nintendo was leaning too heavily on gimmicks.

How did developers feel about it? "The first DS was a bit chunky to be honest, and in the early days I think developers struggled to tame the hardware and use it to their advantage," says Paul Hughes, who worked on a variety of Lego games for the DS at TT Games. "But all said and done, it had 3D hardware, and frankly it was by Nintendo – you never write off Nintendo hardware, they have a knack of mixing things up just enough to force developers to think obliquely and pull off some original games tailored to whatever new hardware quirk came along."

Paul Machacek, who worked on Rare's DS games, didn't feel it to be as odd a design as some did. "When I first saw it there was a familiarity already. Back in the Eighties when Nintendo were doing their Game & Watch line, some of those devices were clamshell folding with two screens, so it felt as if they were simply bringing that form factor up to date with modern games on carts," he tells us, before explaining the challenges posed by the new inputs. "Whilst there were PDAs which had touch-screens, the DS was aimed at gaming and so there would be a shift in thinking for controller-based developers to embrace this new interface. There would be a jump for traditional console developers to think about using a second screen and touch. It really then came down to designing bespoke experiences for this new platform, or cherry-picking existing games to bring across that would fit nicely."

Matthew Castle, who covered DS games regularly in NGamer, admits, "I'm not sure I fully appreciated the DS at first glance. Back then you often thought about new hardware in terms of graphical grunt, and I was a bit too eager to focus on how good Mario 64 looked on a handheld, rather than the potential of its strange form factor. A handheld N64 is an attractive pitch, but it's definitely not how I think of the DS now. It was the weirdness of what followed, enabled by its dual screens and colourful inputs, that really resonated."

What of the claims that the DS would be a 'third pillar' of Nintendo's hardware strategy? "I hoped it was true because I loved the GBA," says Simon Miller, who regularly covered the DS in nRevolution. "It was never going to happen, though, because it would've been nuts. Why would a developer invest time in the GBA when you have the DS pushing things forward? I seem to remember some games got dual releases but again, it meant whatever happened to the GBA version wasn't the real deal – the innovation aspects had been taken out. It also always makes sense to stride forward and leave the last iteration in the past. There's never a need to try and hedge your bets that way. If you're done, you're done!"

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

The Nintendo DS launched on 21 November 2004 in North America, followed by Japan on 2 December. Demand in these two territories was enormous and Nintendo had already shipped 2.8 million consoles by the end of the year, exceeding the company's own forecasts by 800,000. In 2005, Australia received the system on 24 February and Europe followed on 11 March. Paul Monaghan, editor of Pixel Addict magazine, remembers the build-up to the DS launch while working at Gamestation. "With a strong launch line-up you were expected to push the bundles ranging from £104.99 to around £200 including carry cases, extra stylus and of course games. The likes of Super Mario 64 DS and WarioWare: Touched! were in high demand, Zoo Keeper and Project Rub a close second tier and then the rest were mainly picked up as afterthoughts."

Launch day itself was hectic. "The Gamestation I worked in was inside a Blockbuster Video store. This meant we closed at 10pm on Thursday evening, and had two hours to prepare all customer orders to reopen the doors at midnight," he continues. "Consoles were matched up with the desired games and accessories and before we knew it, it was all systems go until 1am. One full hour of excited customers, keeping a queue moving whilst trying to upsell more DS-related product where possible. Some customers hadn't preordered but were still happy to leave with a game for the DS, as any orders not collected by the end of the weekend would be sold on the Monday. Harsh, I know, but demand was huge!" It certainly was – UK customers bought nearly 87,000 DS consoles in its first two days on the market, breaking the record set by the GameCube in 2002.

"I think there's a reason we don't talk about Yoshi Touch & Go these days and I bet Nintendo knew this"

While sales were strong, some of the early software reflected how developers were still trying to figure out how best to use the hardware. Games that didn't utilise both screens well and employ the touch-screen well tended to be criticised for not making the most of the console's unique features, but the games that incorporated them heavily often came across as experiments as much as full-fledged games. Pac-Pix was described as "little more than a tech demo that's been painfully stretched to breaking point" by games™ and GameSpot's review of Yoshi Touch & Go said that, "The novelty of the gameplay is almost palpable, but so are the game's tech demo roots."

Simon agrees that some games came across that way, but quickly qualifies that. "I don't think I minded that, though. Admittedly dropping full-priced money on games that weren't fully realised wasn't ideal but at the same time, that felt par for the course. It was the same for the Wii a few years later. The early titles were always trying to figure out how to be marketable but also show off what the machine could do," he recalls. "I think there's a reason we don't talk about Yoshi Touch & Go these days and I bet Nintendo knew this, otherwise it would've been a fully fledged Mario game. We can't put the mascot in jeopardy, though, so the poor dinosaur takes the heat instead!"

"In the same way it took a few years to appreciate that the DS' strengths lay in its idiosyncrasies, it took a while to rewire our brains as to what a good DS game was," says Matthew. "I avoided a lot of the earlier 'tech demo' games because reviews scared me off – I don't think critics had the right mindset or language to talk about them in a valuable way. Reviewers saw very short experiences for £30 and dissuaded you on a 'bang for your buck' basis. Whereas now, I think people are a bit more appreciative of one-of-a-kind experiences or games that feel tailored to their hardware. I yearn for interactions that feel this bespoke. Perhaps that's an easier stance to have when you can hoover up oddball offerings for a tenner at CEX."

Fortunately, it was apparent that bigger things were around the corner at E3 in 2005. Nintendo announced the Game Boy Micro, but the final GBA model was something of an afterthought – Nintendo was going all in on the DS. "I thought this E3 was the time when the DS was truly born. What with the Wi-Fi, Mario, Metroid and co it seems like now we are going to be able to really experience what Nintendo had intended from the beginning," wrote Cube magazine reader Randy_Pan in 2005. The magazine agreed, saying that "the lack of decent releases" was holding the system back in the present, but noting that in Japan, "The DS is consistently outselling Sony's machine week after week, and it's all down to strong software such as Nintendogs, Kirby's Magical Paintbrush, Gundam SD and Brain Training." The magazine felt that represented a "good indication of what could happen both here and in the US".

This proved to be somewhat prophetic on a number of fronts. Mario Kart DS was not only the latest iteration of a franchise beloved by core and casual gamers alike, but also represented Nintendo's first big push into online gaming. That was something of a surprise, as the company had given mixed messages around its commitment in this area. While Reggie Fils-Aime had proudly trumpeted the console's wireless connectivity at E3 2004, saying "it's beyond online, it's no-line", just a couple of months later in July 2004, Satoru Iwata told the Japan Economic Foundation that "customers do not want online games". While he didn't rule out the possibility of making online games, he did state his belief that "at the moment, most customers do not wish to pay the extra money for connection to the internet, and for some customers, connection procedures to the internet are still not easy".

"I thought the casualness of Nintendogs, a new Tamagotchi, was really smart and it brought forward the notion of 'comfort games'"

To its credit, Nintendo tried hard to overcome the problems Iwata had identified, starting by making the online gaming service free. Wireless internet access was still relatively uncommon, so Nintendo released a USB dongle to allow players to share their wired broadband connection to the DS. It also signed deals with McDonald's in the USA and The Cloud in the UK to offer free Wi-Fi access to Nintendo DS users. Reportedly, 45% of first-week Mario Kart DS owners in America played online – a figure Nintendo proudly compared to the 18% of Halo 2 owners that had played on Xbox Live in its first three weeks.

Then, there was Nintendogs. "I thought the casualness of Nintendogs, a new Tamagotchi, was really smart and it brought forward the notion of 'comfort games', games that are casual ongoing experiences, rather than tests of skill," says Paul Machacek. The virtual pet game was a key release because it sold mostly to girls and young women, broadening the demographics of the console. It was not only the best-selling DS game in Europe in 2005, but eventually became the second best-seller for the console of all time. When asked to name favourite DS games, Paul Hughes says "I'm guessing everyone said Dr Kawashima's Brain Training! What a lovely use of the touch-screen – holding it like a book!" When this game made its way outside of Japan in 2006, its concept of daily mental exercises proved very appealing to adults, and sold by the bucketload to become the console's fourth best-selling game ever.

Why were those games able to succeed with audiences outside of the usual gaming demographics? "I think it's because of the hardware," says Simon. "All of a sudden you could almost tailor your games to a wider audience because putting a stylus in someone's hand is far less intimidating than a controller. I'm sure we've all played an FPS with someone not well versed and they spend the whole time looking up and spinning around. You've gotta get that down before anything else. With the DS, just use the pen, essentially."

Nintendo quickly sought to capitalise on its expanded audience in 2006. The new DS Lite refined the look of the console, and the Touch! Generations branding was introduced to highlight games that offered a broad appeal and simple touch-screen controls. Print adverts showed a diverse range of players enjoying those games, while TV adverts would show Girls Aloud battling it out in Mario Kart DS and Sir Patrick Stewart using Brain Training. "It was the first gaming campaign that grew so big that other publishers started spoofing it," Matthew recalls. "I'll always chuckle at Steve Davis mimicking Nicole Kidman's Brain Training advert to promote a DS snooker game." With the mid-year reveal of the Wii highlighting Nintendo's philosophy of lowering the barrier of entry to games via motion controls, it was clear that the company was no longer in the business of selling to gamers, so much as selling games to everyone.

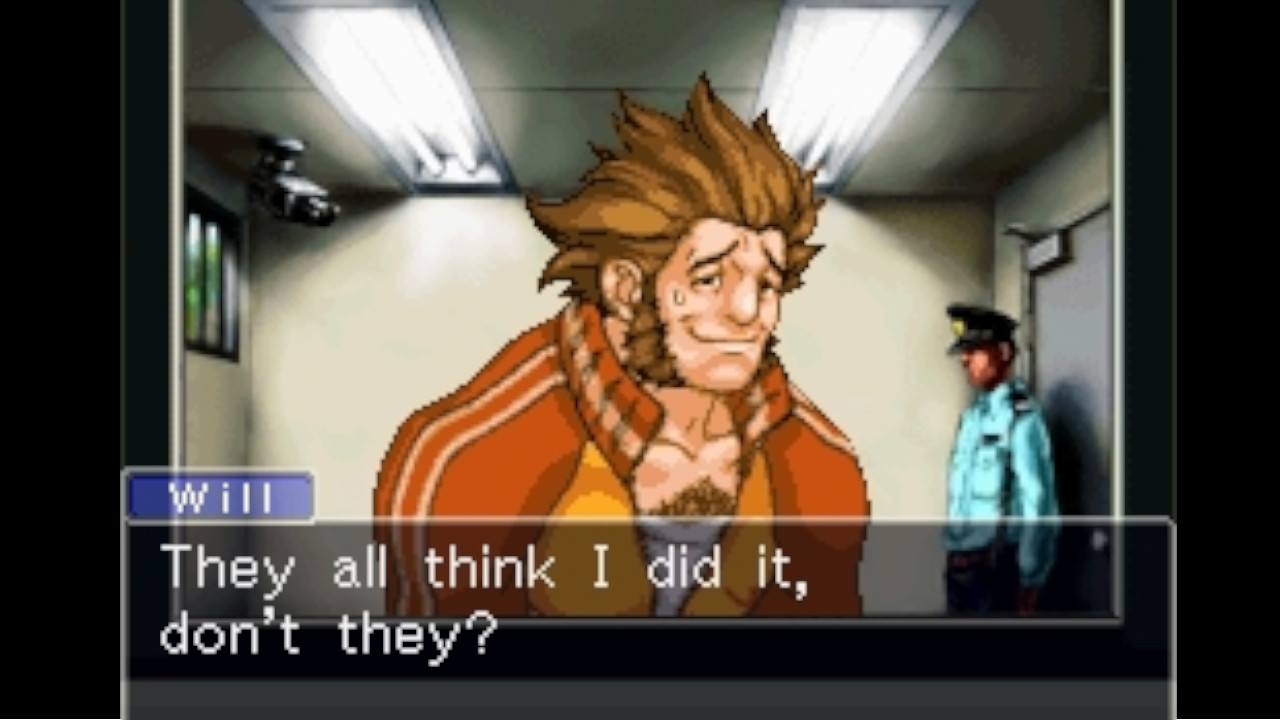

Was it clear to Matthew that the DS was well on its way to becoming an enormous hit? "When ageing relatives mentioned the DS to me unprompted in late-2006 it was clear it was breaking out in a way videogames didn't normally," he confirms. "Also, the fact that sales of our Nintendo magazines didn't explode in tandem – it was so obvious we were talking to a fraction of the audience Nintendo was chasing. It's maybe a bit of a downer thinking about DS as being the result of clever marketing rather than my mum finally appreciating the inherent value of Ace Attorney, but it did feel that way."

Capcom's courtroom drama is an interesting game, because it's a truly beloved DS game. "Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney was lovely, with big and bold visuals, like an interactive manga comic," says Paul Hughes. Matthew agrees, saying, "The Ace Attorney series is an all-timer for me: its fusion of Shu Takumi's mystery writing, the rip-roaring score and storylines that paid off over multiple games felt like an anime you could play." However, the series was already up to its third entry on the GBA in Japan – it was only the success of the DS that convinced its publisher to take a chance on localising it, for which it was richly rewarded as the first game repeatedly sold out.

Other games that would have almost certainly never left Japan before, such as Cooking Mama, were also localised to varying degrees of success. The DS soon became a platform with a hugely diverse range of games. "I think publishers were navigating uncharted territory," says Matthew. "Nintendo were rinsing the charts with virtual puppies, maths exercises and pub games, as well as excellent versions of some fan favourites; looking at that and extrapolating a winning formula must have been a nightmare. EA made an RPG, Zubo, about anthropomorphic drum people! It was absolutely baffling, but good fun seeing people scrabble for a piece of the pie."

Paul Machacek found himself working on the core end of the spectrum. "I suggested a port of Diddy Kong Racing for DS as it had been so successful a decade earlier, but knew that we needed to apply it appropriately to the hardware. There were also a few things in the original game that felt like they needed changing," he says. "We looked at the different hardware characteristics of the DS and tried to find features that could use them. The idea of blowing into the microphone to get a turbo boost was a quick off-the-cuff idea. Recording your own sounds with the microphone and applying them to in-game events was unique and allowed people to customise the game with the extra comedy of other players experiencing such sounds in multiplayer."

"I suggested why don't we allow players to draw their own track?"

"The big challenge was really what do we do about touch," he remembers. "A member of the team suggested adding more tracks (which we did do) because 'more is better!' but I didn't agree with that standard sequel approach, and it didn't feel like a DS-specific thing to do. But 'touch' and 'new tracks' lingered and I suggested why don't we allow players to draw their own track?" Paul's idea stuck, and the team got to work. "We hacked out the basics of this pretty quickly. It had to be easy, fun, so we went with a set of standard block track pieces that could link together, and by drawing a squiggly line that would join up with itself we could then turn that into a corresponding track with the building-block track pieces. To keep collision detection easier and not have to worry about off-track scenery and furniture, we put it up in the sky so that if you drove off the track you would fall."

Viva Piñata: Pocket Paradise was an easier adaptation for the team at Rare. "Viva Piñata naturally lends itself so well to touch, with a stylus, because you can accurately point at things, click on them and control a shovel to directly terraform the garden with the stylus," explains Paul Machacek. "We were only going to put the garden in one screen, the touch-screen predominantly, and we designed a HUD with icons to access the tools, seeds and shop. There is a second important part of the game though as well with the Encyclopaedia, and being able to have that on the top screen for direct reference really helped simplify the game. We allowed players to swap the screens around so that you could touch the Encyclopaedia pages and everything in them (Pinatas, plants, seeds, tools, etc) were shown using standard unique icons which were clickable."

Paul Hughes remembers the challenges of trying to adapt multiplayer games for the unique hardware. "Certainly, with the first few Lego games we did our level best to match the core mechanics of their console brethren, but at the same time knew that due to the dual screens we could add extra minigames to make up for bits that we were forced to miss," he explains. "For example, we couldn't have a full character party on-screen at the same time, so we had to swap in the co-op character via the touch screen. But then on Star Wars we had the dual screen rendered AT-AT section on Hoth tying up their legs, or the lightsaber training with Luke."

One game that Paul Hughes remains particularly proud of is Lego Star Wars: The Complete Saga. "Just getting the entire console game crammed into 64MB was a Herculean feat; especially as we went for all digital audio – I had chance to use John Williams' score played by the London Philharmonic, I was going to make that happen by hook or by crook," he recalls. "The camera and control systems were tailored for the DS as it only had digital d-pad input so we didn't want to hamper the player hitting tricky diagonals whilst the camera shifted around. Add to that we had to be very careful with camera framing to make sure you saw far enough ahead to not get 'pounced on', but at the same time to not blow the 4,000 vertex limit which would cause chunks of polygons to disappear."

The DS hit its commercial peak in 2008. That same year, Forbes' Brian Caulfield noted that Apple's iPhone had the touch and motion controls that had made Nintendo's DS and Wii so successful, and that, "The ability to pour fresh software into the iPhone, wirelessly, at the touch of a button" via the new App Store could cause Nintendo problems. The DS got its own downloadable game store the same year, but it was only available to owners of the new DSi model. Meanwhile, the 2009 mobile game Angry Birds could easily have been a DS game, and by 2011 PCWorld opined that "The Nintendo DS and the Sony PSP are still selling, but these portable game gadgets seem like relics from an era when people used cell phones strictly to make and receive calls." Nintendo released the 3DS that year, and while the backwards compatible successor to the DS was a popular machine, it never came close to the heights of the original, which is still the best-selling handheld of all time with a staggering 154 million units sold.

"Square Enix did beautiful JRPG work with the Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy remakes"

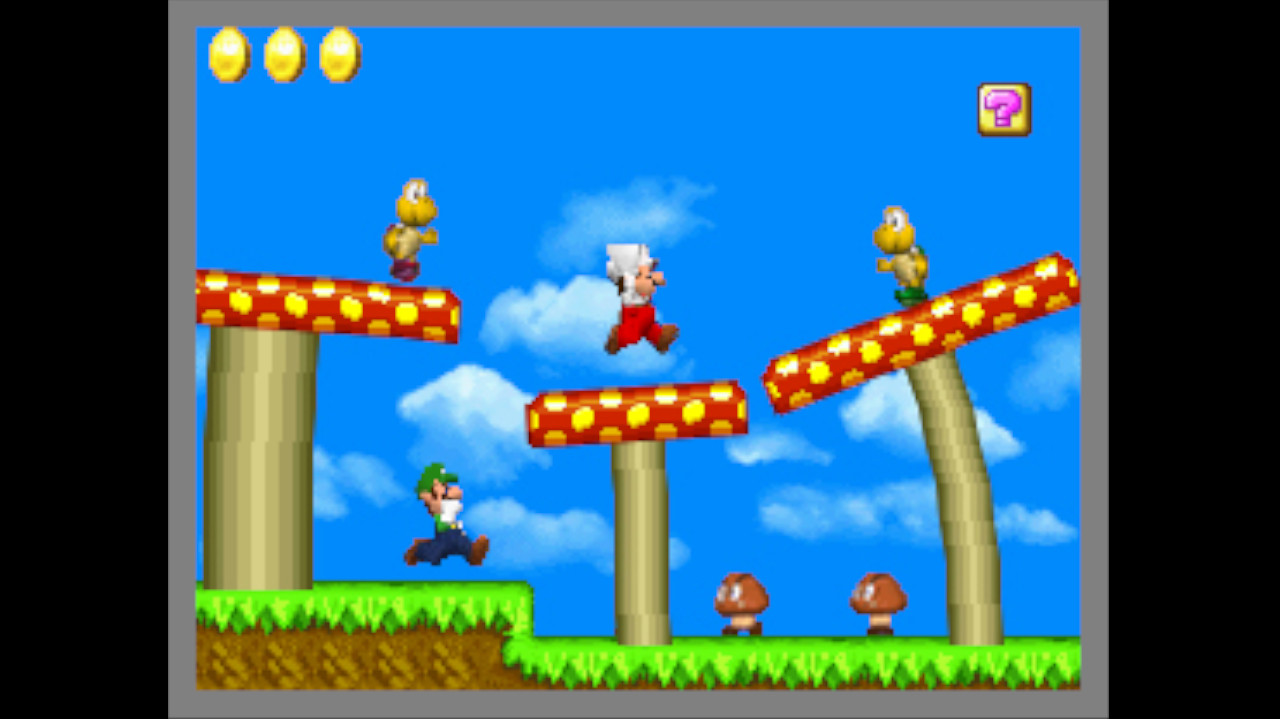

Some players are quick to deride this era of Nintendo, bemoaning a 'casual' focus and pointing to shovelware like Russell Grant's Astrology or Ubisoft's much-derided Imagine series. "While it's true DS had a lot of games outside of that traditional scene, it was really hot on several core genres," Matthew points out. "Square Enix did beautiful JRPG work with the Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy remakes, Atlus were drowning us in Shin Megami spin-offs, and there were loads of weeb-y adventure games and visual novels for Japanophiles." The console really does cater for all tastes, from the ridiculous shoot-'em-up action of Bangai-O Spirits to the sedate puzzles of Polarium. In fact, the console's best-selling game was New Super Mario Bros – an extremely traditional revival of the 2D platforming formula that made the character famous.

"Nintendo managed to master the whole age range with the DS (and later Wii), they just had that magic formula," says Paul Monaghan, summarising the appeal of the console. "Game series such as Mario and Zelda catered for gaming diehards and non-gamers or those returning to the hobby would eagerly buy Brain Training, the Professor Layton titles or even the many shovelware titles featuring classic puzzles. The ease of pick-up-and-play gaming was brought to the mainstream and Nintendo wanted everyone to be part of that. Being able to interact with games with the stylus helped you feel more involved and just like the original advertising campaign requested – you just had to touch it."

And really, you still do have to touch it. As the Wii U's Virtual Console releases proved, the unique features of the DS mean that its games just don't quite feel the same on other devices. So get some friends together, send crude drawings to each other in Pictochat and then blast each other with blue shells in Mario Kart DS – you won't regret a moment of it.

Nick picked up gaming after being introduced to Donkey Kong and Centipede on his dad's Atari 2600, and never looked back. He joined the Retro Gamer team in 2013 and is currently the magazine's Features Editor, writing long reads about the creation of classic games and the technology that powered them. He's a tinkerer who enjoys repairing and upgrading old hardware, including his prized Neo Geo MVS, and has a taste for oddities including FMV games and bizarre PS2 budget games. A walking database of Sonic the Hedgehog trivia. He has also written for Edge, games™, Linux User & Developer, Metal Hammer and a variety of other publications.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.