Prey: Breaking and remaking the rules, as BioShock meets Dishonored

For a long time, I’ve bemoaned this generation’s lack of a BioShock moment. Don’t get me wrong, games have been brilliant since 2013. The console hardware has increasingly shown its might, and game designs have evolved very nicely indeed from their last-gen roots. But it’s been a process of small, incremental upgrades rather than true revolution. Both visually and in terms of gameplay, there hasn’t been one, single game that has stepped forward to claim ‘Things have changed’. Not the way that BioShock did, when its combination of FPS, RPG, and sumptuously blended world, narrative, and emotional and philosophical heft landed in 2007.

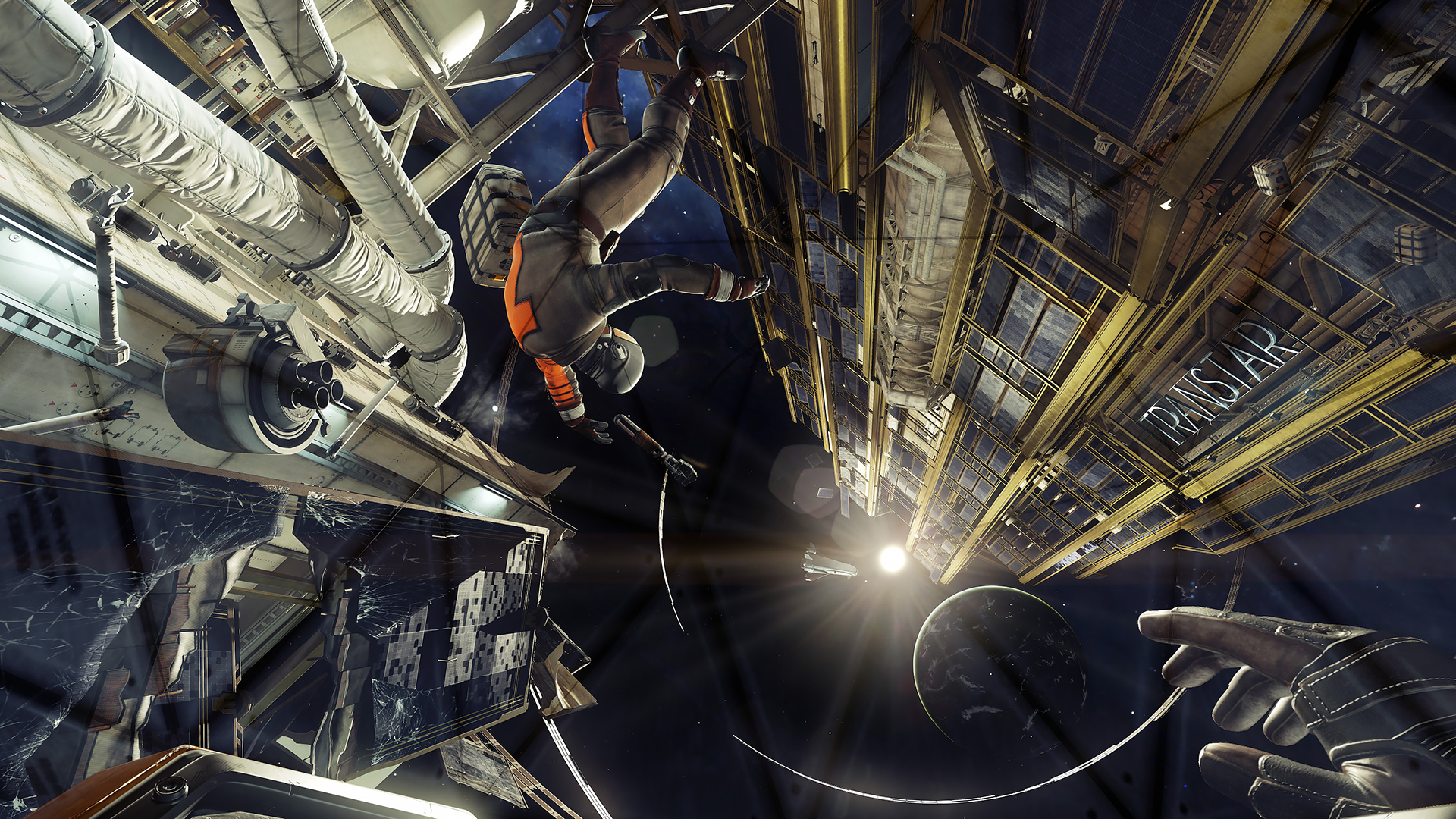

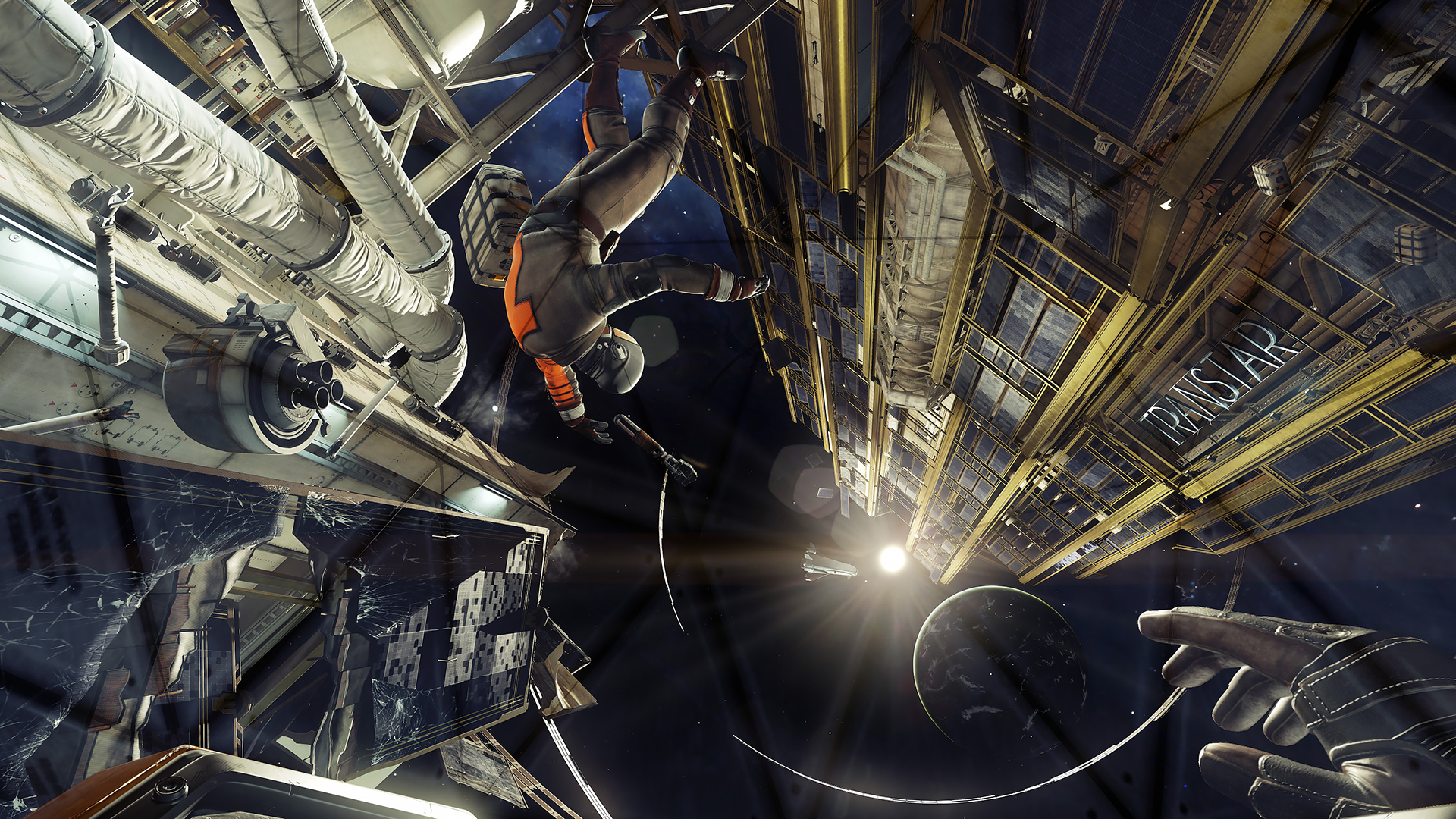

But I think we might be about to hit that moment. Because Prey, coming in 2017 from Dishonored developer Arkane Studios, might well be that game. Set in a world where Kennedy was never assassinated, and redoubled his efforts in the space race, it presents a 2035 in which the Talos One space station has orbited the moon for 70 years. Humanity has evolved its presence in space exponentially since the station’s launch, building layer upon layer on the habitat to create a technological onion of different eras, modern sheen peeling back to reveal the ‘70s, and then deeper still, the environment’s chunky, clunky Russian roots.

But humanity is trying to evolve in other ways. Experiments are being done in an attempt to expand the human experience. And they’re about to succeed, though not in the ways intended. The human experience is about to get really shitty.

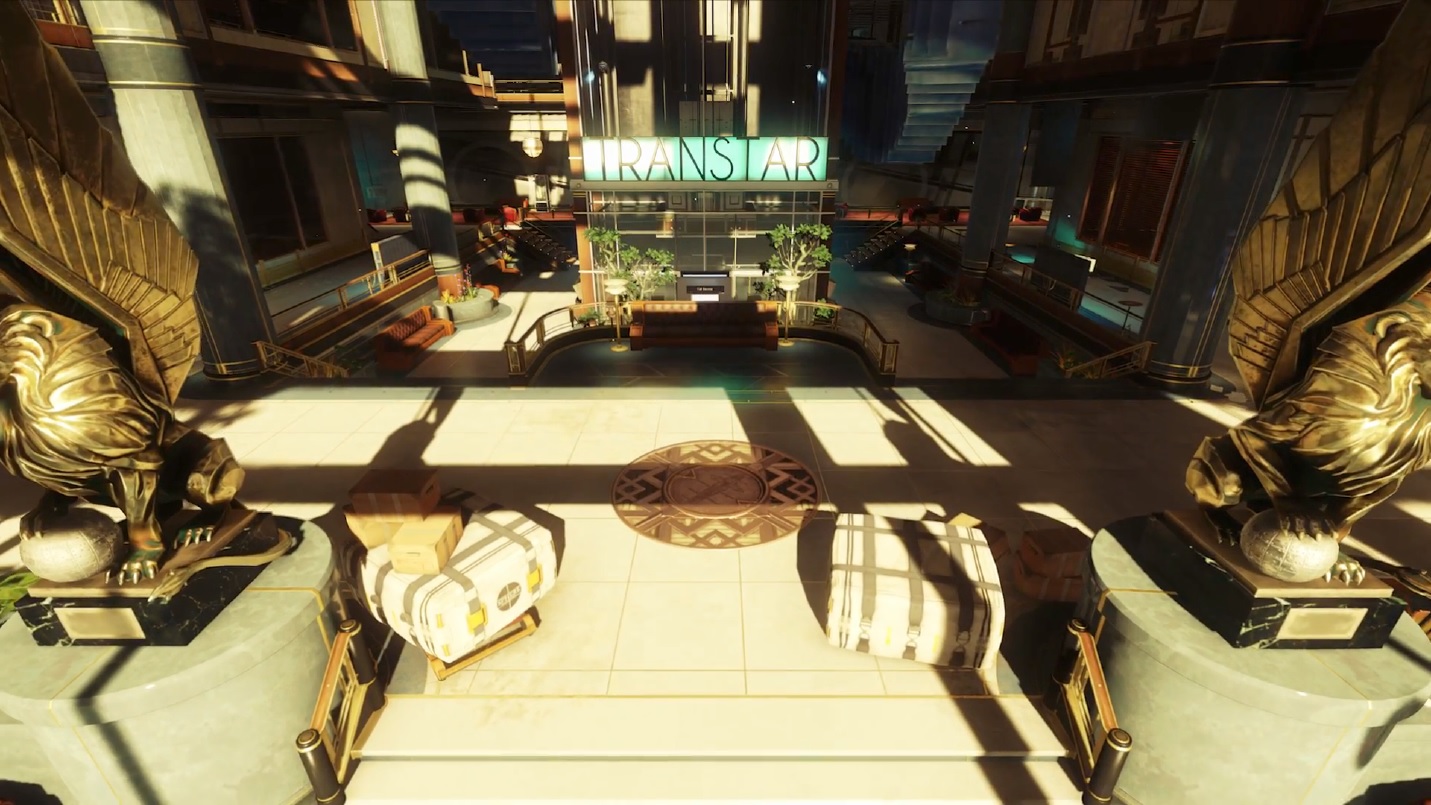

As Morgan Yu – the gender-agnostic name is deliberate; you can choose at the start – you wake up on Talos One immediately after an unnamed atrocity has begun wreaking carnage through every deck and hall. Alien beasts are running rampant, swirling, skittering nightmares of rag and fog and shadow. People are dying unpleasant deaths, and the monsters are everywhere. The monsters are everything. These extraterrestrial wraiths have the ability to mimic any object on the station, only revealing their true form when they’re close enough to strike. That trash can on the floor? Don’t trust it. That suitcase discarded in the lobby? Better double-tap it, just to be sure. And hang on, did that chair just move?

But if you can’t trust the world around you, at least you can trust yourself, right? Well not necessarily. Where BioShock brought us DNA-warping Plasmids, Prey allows you to upgrade yourself with both human tech and alien material. Get close enough to the monsters and survive, and you can study their abilities. Learn enough, and you can emulate their behaviour. But should you? The choice is entirely yours. You can harness or reject any alien ability you wish. They bring great power, naturally, but Prey’s dynamic, reactive world will be watching you, and it may not like what it sees.

“When you do that there are consequences”, Arkane’s Ricardo Bare tells me. “The more alien material you put into yourself, the more things start to change. Things like the station's turrets. They protect humans and shoot aliens. But guess what? You've got alien material in your head now. And some of the aliens themselves are sensitive to other creatures that have powers like them. So they'll start to detect the fact that you are upgrading yourself that way, and they'll come after you.”

That’s the risk, but what about the reward? Well here’s where it gets silly. Forget the simple process of jamming oversized hypodermics into your arm to gain multiple elemental Hadokens. In Prey, things are much more freeform. Much more Dishonored, in fact. Your abilities aren’t so much solutions to specific problems, as malleable tools to do with whatever the hell you wish. In much the same way that Dishonored’s Blink teleport is ostensibly a handy traversal tool, but also opens the way to as many ludicrous, almost game-breaking combat puzzle strategies as one can imagine, so too are Prey’s powers building blocks rather than linear solutions. You might use them to kill enemies and bypass obstacles, but Prey’s gameplay looks to be far more about creation than destruction.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Take the Gloo Gun, for instance. A large, sticky goo cannon, its ammo will rapidly set, freezing any enemy you train it upon. So far, so good. Throw in a grenade. Hit them with a flame attack. That will work. Or maybe those stricken bodies will work as cover? Or maybe you can skip the fight altogether. Maybe you can sneak to a safe spot at the side of the room – stealth is abundantly viable in Prey – and spray the goo up the wall, letting it coalesce into a set of convenient platforms with which you can merrily skip up to a higher level.

Sorry, did I say that was where it got silly? I lied. Because now I’m going to talk about that stealth. And this is where it gets silly. That thing I said about how the aliens can mimic objects on the station? And that other thing about how you can adopt the aliens’ powers? Yep. Becoming more alien might attract the aliens, but they’ll have a much harder time finding you if you’re a teacup.

And the best part? You maintain your other abilities whether you’re made of flesh or porcelain. So forget the Gloo Gun if you don’t want to use it – or perhaps aren’t in a position to. Turn into a ball, roll over to that platform – you can move around as any object, by the looks of it, including the cup – drop a kinetic charge underneath yourself, and tee off to wherever you want to go.

If all of this sounds potentially ‘exploitable’, then you’re right. And Arkane is not unaware of the issue. But, being Arkane, it doesn’t seem to care as long as the gameplay is good. As Director Raphael Colantonio explains,

“It's a weird balance, allowing the things that are not initially pre-planned until it becomes a game-breaker. If something is too much of an exploit then we need to fix it. But usually - if there's something that is cool, but it's not quite polished, like some sort of weird interaction that works magically, but is a little bit of a problem - then we'll support it, because now we want it to be part of the game. But ultimately we really like this. We like it when players break the game in a good way and find some weird shortcut to a situation, and feel really proud that they could beat the game in such a way.”

But isn’t that a nightmare from a designer’s point of view? After all, Prey is no linear, point-to-point game. It has far more in common with Metroid. While its story and missions will lead you along the ‘correct’ path, the whole station is being built as “one giant space-dungeon”, according to Bare. “You can go anywhere you want as long as you have the means to get there. And just like in those old-school RPGs, we let you go to parts of the station where you might not have any business being there, because the monsters there will just smash you down. But it's still cool knowing that I can do that, that I can try if I want to.”

And with secrets, other survivors, and the overwhelmingly human instincts for exploration and rebellion driving you, you will want to. But how does a studio reconcile that sort of structure with the knowledge that – just as happened in Dishonored – its players could quickly concoct combinations of powers that no-one making the game ever considered? According to Colantonio, it’s all about breaking down obstacles into core challenge types, and trying to stay on top of – and open to - the appropriate tools the player might have.

“We look at it like challenges that are not quite directly linked to a power. So for example there could be the challenge of elevation. 'How do I get on the other side of this thing?'. Then we have a set of systems that can deal with that. And so it doesn't really matter which one you use. You could use the Gloo Gun there, you could have a lift power to create some sort of field of upward force which you could use to propel yourself.

“We could say also there's the type of challenge where you have to get on the other side of a wall and there's some opening somewhere. And you could turn yourself into a smaller object if there's one around you, or just drop one from your inventory and turn into this object if you have the power. Or maybe you could turn into smoke and go through that way.”

Not that Prey is all puzzle solving and rule breaking – though there is a “heavy element” of that, according to Bare, growing from the team’s love of environmental disaster-management in games like FTL. The station is also “infested” with enemies, ranging from skittering crab-bastards to hulking great ghost-ogres. Direct combat is entirely feasible, but with weapons at a premium, you’ll again have to get more creative. And again, you’ll have to the tools to do that. Most interesting among them is the Recyclotron, a grenade that breaks down matter into its constituent parts and then hoovers it up into resource units for crafting. Imagine a throwable version of No Man’s Sky’s Multitool and you’re basically there. Only rather than deconstructing rocks and plants, the Recyclotron works on anything that isn’t nailed down.

And once you have those resources? Time for crafting. The crafting of pretty much anything you want, in fact. Weapons, gadgets, human tech to gain further abilities, or just nondescript junk for throwing on the floor and turning into. And if you’re still stuck for ideas after all of that, why not craft a propulsion system for your hazard suit and go outside for a nice, head-clearing space-walk? Because yes, you can do that too. You can freely fly around the station and re-enter the structure anywhere you fancy.

Prey is silly. Prey feels almost too freeform. It feels vaguely impossible to wrangle. But that’s why it’s exciting. That’s why it feels new and important. Most of all, it’s Arkane’s willingness to allow the game to get out of control, to only reel it in when needed, that makes it feel like a step forward. Prey’s developers seem as willing to break the rules and remake them as the game’s players will no doubt eventually be. And if the studio’s previous game proved anything, it’s that a blatant disregard for the rules is often where the most fun comes from.