Alien: Isolation's long-term play is intimate, intelligent, and excruciatingly intense

By this point, we all know that Alien: Isolation is very scary indeed. We all also know that it is very clever; its titular, AI-driven beast fuelling an unpredictable, emergent ecosystem of jaw-clenching terror on a pretty consistent basis. There’s one question that’s been left un answered. One last, desperate, misanthropic shred of hope to cling to for the idiots who can’t get over Colonial Marines, and are inexplicably desperate for Creative Assembly’s game to be shit as well.

That question is this: While all of these vertical slices and half-hour chunks of intensive fear are very well and good, just what the hell is Alien: Isolation like in the long term? Surely it can’t keep up that pace in a sustained fashion and still work as a game? Okay, that’s two questions. But pedantic maths aside, the answers are ‘Gruelling, but rather lovely with it’, and ‘Oh hell yes it can’.

I’ve recently had the chance to play a good few uninterrupted hours of Alien: Isolation, on my own time and free from the distractions of traditional preview events. And over the course of those relentless, harrowing hours, I discovered that there’s a great deal more going on than a simple game of hide-and-seek with a seven-foot, extraterrestrial killer. Now on the surface of it, that’s of course exactly what the game is about. But it’s only with prolonged play that you can really get a feel for just how much extra, clever, layered stuff Isolation is doing as an overall production. And it all adds up to a one hell of an intelligent nightmare.

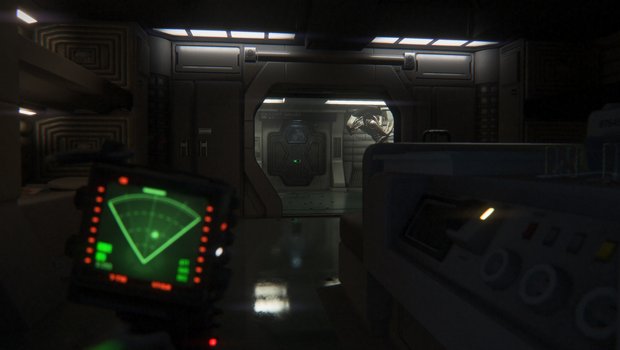

Starting with the slightly more obvious things, it’s only through a few hours experience of the game’s environment that the real power of its all-consuming atmospheric design comes through. I’ve discussed at length the authenticity of Isolation’s disturbing recreation of the Alien universe, but once you get past the outstanding surface detail, a wealth of granular touches amplify that yet further.

For instance, the underplayed character dialogue is pitch-perfect. Sparse, quiet, and all the more affecting because of it, it’s not only 100% authentic to the character aesthetic of the film series but also damnably effective at creating a tense, doom-laded atmosphere of heavy, ever-present dread. And then there are the non-Alien scares.

Rest easy. Isolation is not a game of cheap, scripted, cat-in-a-cupboard shocks. To include their like would completely undermine the stunning work being done in making the xenomorph itself such a living, dynamic threat. Rather, I’m talking about the little, almost subliminal, corner-of-the-eye things. The air vent whose iris-shutter automatically opens as you walk past. The perpetually rocking desktop toy that adds an uneasy sense of movement to the scene, and a nasty jolt when you forget about it and turn around.

All of these things, along with the constant rise and fall of the Sevastopol station’s ambient soundtrack--all venting pipes, distorted security messages, and ambiguous, thumping, screeching, mechanical noises--conspire to create a long-term unease. It's an ebb-and-flow of never-quite-released tension that permeates every room and corridor.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Then there’s the Alien. There’s always the Alien. Because whether it’s tangibly apparent or not, it’s always present. Between its immense physicality--informed by both its size and the horrifying amount of character in its movements throughout all of its states of alertness--and the knowledge of how hard and ruthlessly fast it hits when it spots you, it dominates every area of the game. Even when it’s not there.

Its whole aura--the knowledge of what it is, what it’s capable of, and how rapidly it can appear and strike--combined with all of those ambient, ambiguous, environmental stresses to create an ever-building feedback loop in which the beast is surely always watching you. It’s always above, or below, or around the corner or right behind you. The only time you can know it’s not silently, stealthily hunting you down is when you can see it right in front of you. And at that point, you’re dead.

And it never gets less scary. Not ever. Obviously the creature’s lack of prescribed movements, and total disrespect for traditional stealth-enemy behaviours, mean that you can never get used to its presence. But over the course of prolonged play, it’s the intimacy of the whole experience that will get you. Where most video game enemies become lifeless, exploitable, mechanical beings through later familiarity, the Alien only becomes more lifelike and more disturbing.

You won’t learn any patrol patterns, because there aren’t any, but you will learn to read its physicality. You’ll learn to understand what that particular turn of the head means, and what it’s thinking when it makes that particular noise. But none of that knowledge will tell you what it’s going to do next. You’ll never be able to tell that a certain walking gait means that you’re free to take a certain course of action. Just what sort of mood the Alien is in, how aware of you it is, and how closely it’s on your trail. Over a longer period, all of this creates the picture of an even more real creature, its individuality and independence informing and expanding the endless cat-and-mouse game, and eventually turning the hunt into a relationship.

And that changes everything. After a couple of hours, if you’ve been paying the unswerving attention required to stay alive, you’ll start to notice a wider, deeper meta-game at play. The motion tracker’s blips and pings at first seem vague and unwieldy compared to a modern video game radar--and indeed, they are--but when forced to eke each and every possible advantage out of your situation, you’ll eventually find new, inexplicit uses for it.

You’ll learn to read the unseen parts of your immediate environment via the Alien’s abstracted movement through them. You’ll loosely discover where the Alien’s invisible entry and exit points lead, vaguely mapping out its hidden network of forbidden vents via its ‘impossible’ movements on your little green screen. You’ll learn to translate the pitch, speed and urgency of the tracker’s pings directly into unseen Alien behaviours, those low-fi blips from that low-tech speaker ultimately morphing into a kind of voice for the roaming monster, communicating its thoughts and behaviours directly to you.

And none of this ever makes the game easier. Or less scary. Or less intense. In fact it only ensures that you’re constantly thinking, constantly on edge. You’re always alert to any movement. You’ll always, instantly, scan every new room you enter for hiding places and escape routes, the moment the door opens. Your disorientation and confusion will always be compounded by your need to define your explorative movements by the pre-emptive evasion of something that may or may not even be there at all. Above all, the Alien will infuse every element of your experience with its presence.

It will change the way you think, it will change the way you see the world around you, and it will inform every single way you interact with it. All of that makes the tension relentless, to a degree that may even be uncomfortable for some. But it will also remind you, perhaps even show you for the first time, what the words ‘survival’ and ‘alien’ really mean.