Revisiting the Question by Denny O'Neil and Denys Cowan

Revisiting an interview from 2002

This piece originally ran in 2002. Since then, Denny O'Neil has sadly since passed away…

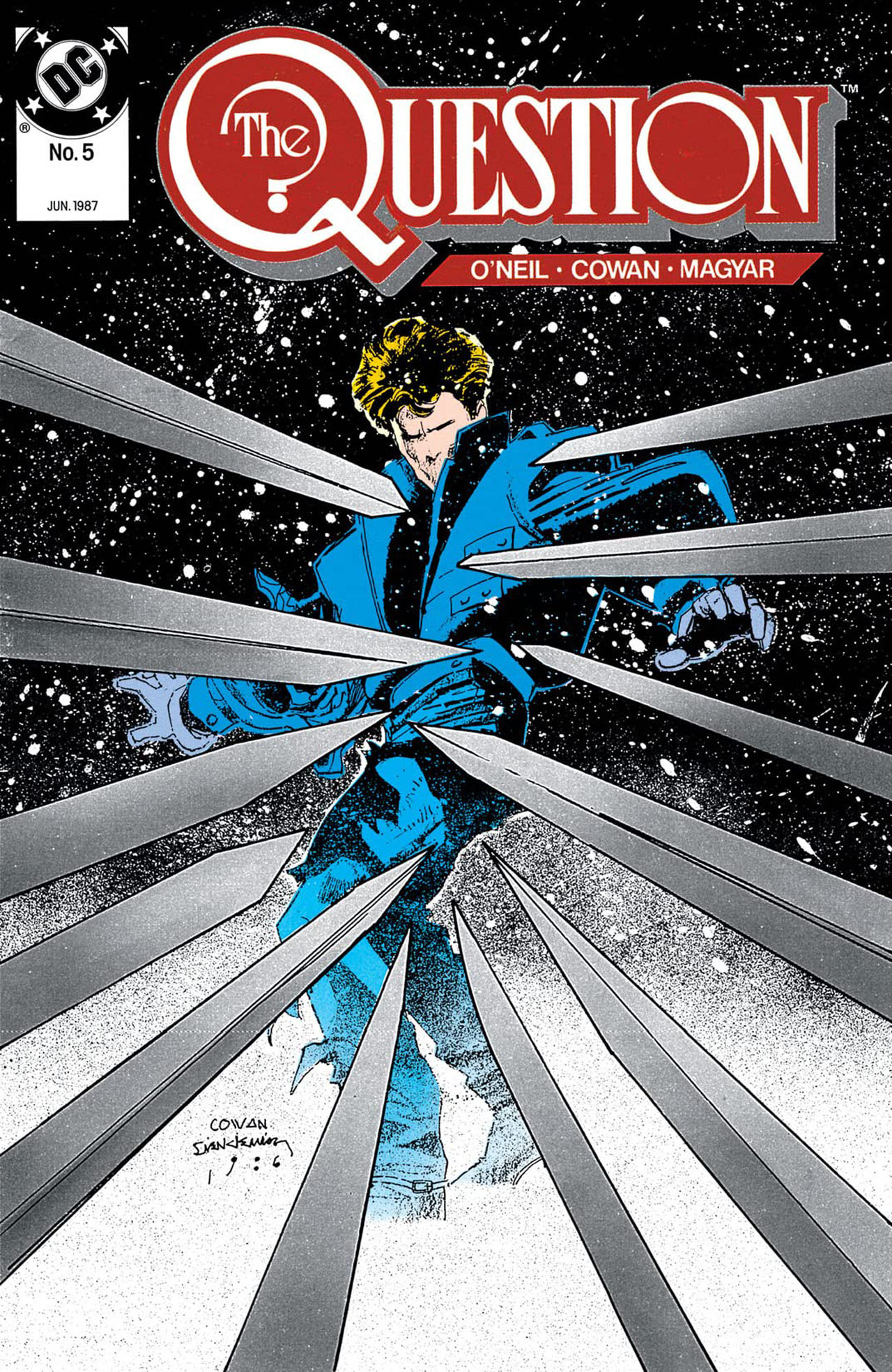

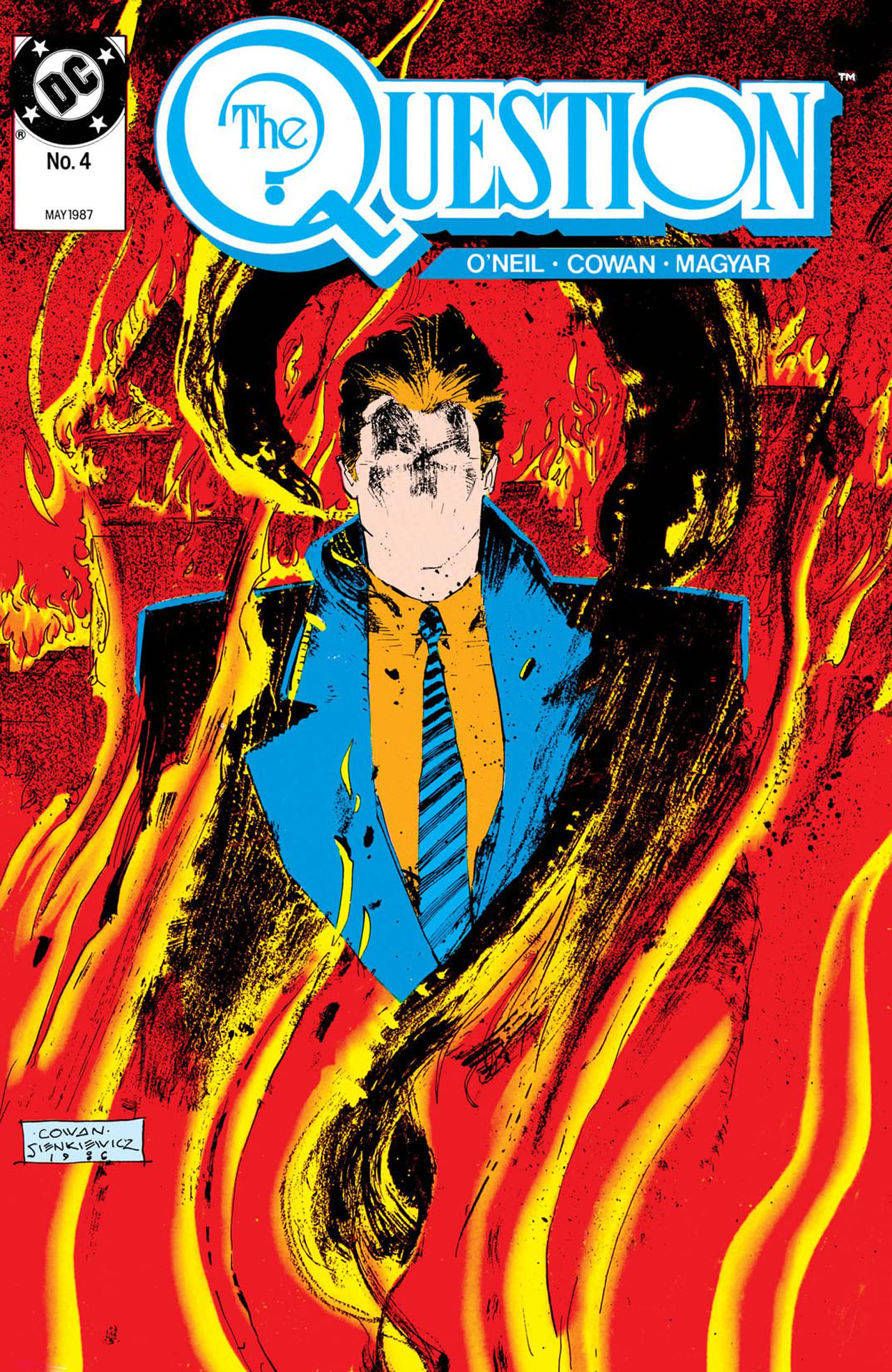

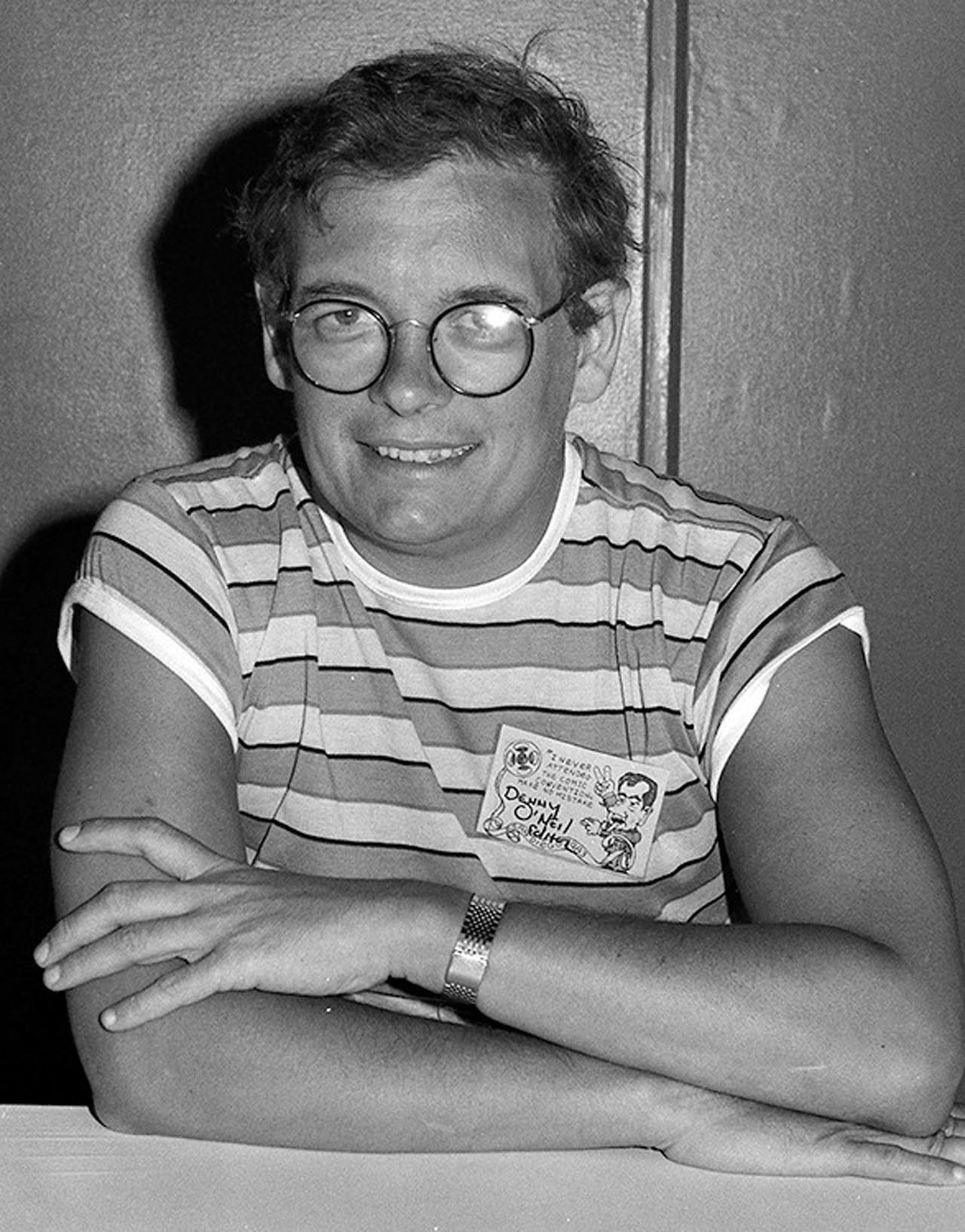

While 1986 and 1987 are what many modern comic readers consider the recent golden age, there's a book from that era that often gets overlooked. Sure, DC had Watchmen, The Dark Knight Returns, The Man of Steel, Wonder Woman, Crisis on Infinite Earths, and Green Arrow: The Longbow Hunters during that time, but they also had The Question, written by Denny O'Neil.

The series typified two of the strongest themes of the zeitgeist of the time, experimentation mixed with some deconstructionism. And it turned out quite well.

But from the start, The Question wasn't a case of a dream job for O'Neil, who had just returned to DC after a lengthy stint as an editor/writer at Marvel.

"I was barely aware of the character," O'Neil said. "Writing The Question came about because I had been editing at DC for about six months, and I was hired as a hyphenate, as was Archie Goodwin, as a writer-editor. I took a vacation from writing, just doing a couple of short stories and a monthly From the Den thing, but I basically didn't do much writing."

While not writing loads of comics when his position clearly said he was a comic book writer may sound odd to comic book fans, O'Neil stressed that he was one of the few in the comic book business who was not a comics fan when he came into the industry. It was a job - a job he did well, but a job.

"I was getting a salary and didn't need to write, but to my mild surprise I found that I really liked it," O'Neil said. "I had been telling stories in one way or another since I was seven years old, and I was surprised at how deep that instinct is. You really have to enjoy the process on some level - which isn't to mean that there aren't rotten days or rotten months."

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

At the same time, O'Neil realized he was ready to start writing comics again, his superiors at DC had begun to gently suggest that he get back in the saddle again. Thanks to their recent acquisition of the Charlton stable of characters, there were two characters available for ongoing series - Captain Atom and The Question.

"Captain Atom was a Superman kind of guy," O'Neil said. "I can write those kinds of 'god' superheroes, but I'm not comfortable doing it. So, I opted for a ground level, very human character, which was The Question."

The character decided upon, O'Neil had a rare luxury in comics - time to prepare. Together with editor Mike Gold, with whom he was sharing an office at DC, O'Neil reviewed the entirety of what Question work had been published to that date - all 64 pages worth and figured out how to take it in a new direction. When they pitched the idea to then DC executive editor Dick Giordano, he immediately approved it.

A bit of history - Giordano's approval of an O'Neil Question series was a nice touch of fate. Both Giordano and O'Neil both worked at Charlton in the '60s, and Paul Levitz helped acquire the Charlton heroes as a favor to Giordano in the '80s. It was a miniature Charlton reunion under the DC banner.

"Mike and I spent an unusual amount of time talking about it and getting ready to do it," O'Neil said. "Another interesting thing that happened around that time occurred when I was on a DC corporate retreat.

"I was coming back from lunch with Paul Levitz, talking with him about my beginning to write again, and he said, 'Once upon a time, you pushed the envelope, and then for the last seven or eight years, you've been doing solid, mainstream stuff at Marvel. If you want to push the envelope again, that's fine - don't worry about making this commercial - just write something that you really want to write.'

"That was very refreshing coming from the guy whose responsibility is the finances of the company. But Paul is also in his soul, a fan. I had never before been given that much freedom going into something - to just make it good, and make it what I wanted it to be."

To turn the character - and the series - into what he wanted though, O'Neil had to alter the character from its Ditko/Charlton roots, something that would be problematic down the line, given that this was 1986, and loyal fans of the original Question were still around the industry.

Ditko's version of The Question, as seen by O'Neil was a right-wing vigilante. Reading O'Neil's work over the years makes it pretty clear that having him write a conservative vigilante would be akin to fitting a round peg into a square hole. But this is comics, and there are rules to how you can fundamentally change a character.

O'Neil killed The Question.

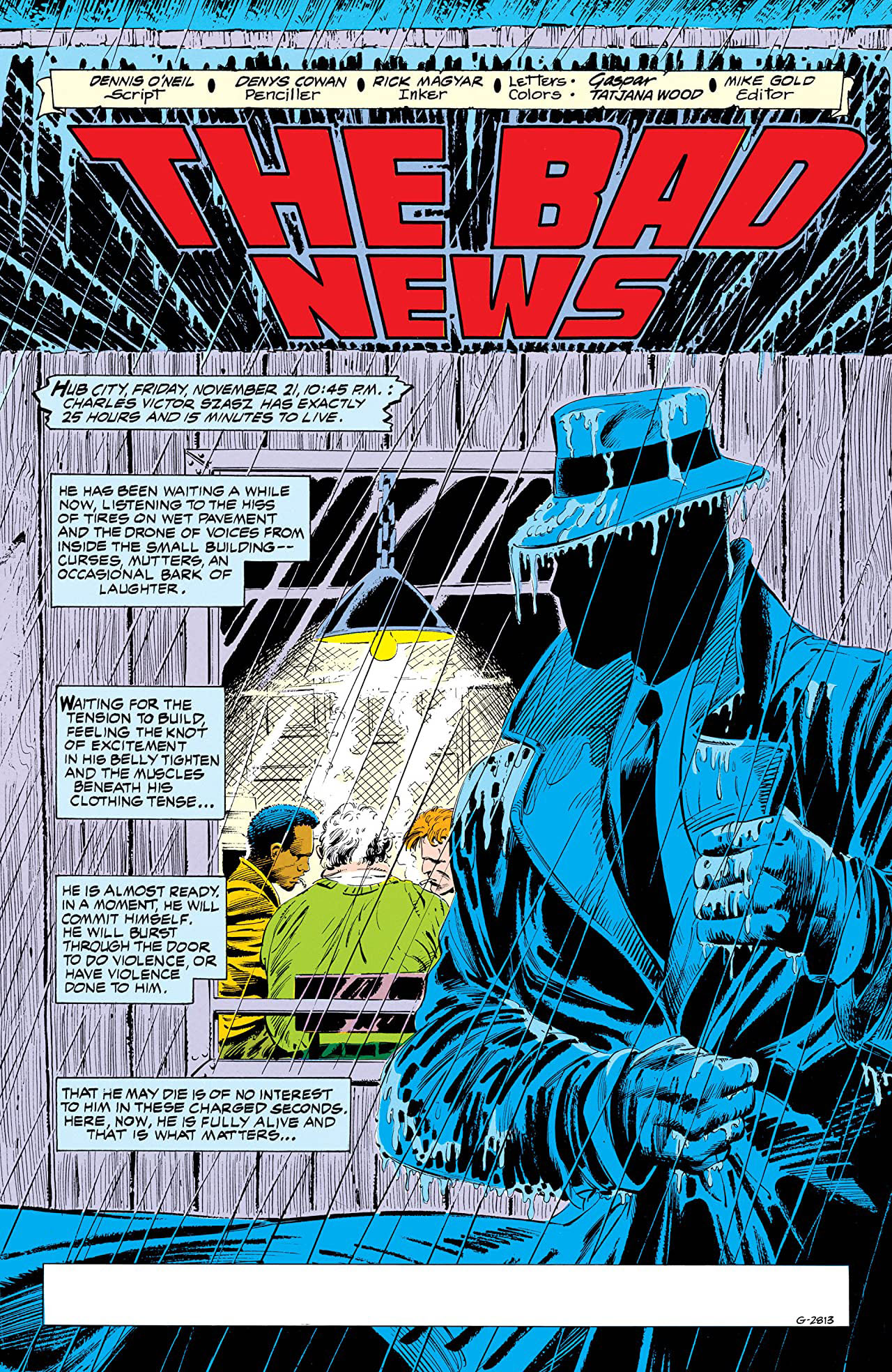

Well, symbolically, at least. As a result of sticking his nose in where it doesn't belong, Vic Sage, The Question gets his clock cleaned by Lady Shiva, beaten down by thugs, takes a bullet in the head, and gets dumped into the drink. The final panels of The Question #1 show a lifeless body on the bottom of the river. Pretty depressing, but very symbolic of what O'Neil wanted to accomplish - the old Vic Sage was broken and dead, allowing a new man to take his place.

"If I accepted the assignment, I was going to change the character," O'Neil said. "That's why in the first issue, he dies, symbolically, to be resurrected in the second issue. I thought that was a strong story point, and it was also our way of saying that the old Question is dead, and this was something new."

From then on, O'Neil was able to use The Question to explore his own interests as well as many moral and social issues. Anchoring the series firmly within the DC Universe, O'Neil had Batman himself give Sage a pep talk of sorts in issue #2, before sending him off to the tutelage of Richard Dragon, the same mentor to whom Greg Rucka would have Sage send the Huntress to in 2001's Batman/Huntress: A Cry for Blood limited series.

Dragon "rebuilt" Sage from the ground up, instilling in him ideas of Zen philosophy, as well as shoring up his martial arts training. Dragon also hit the nail on the head when it came to Sage's motivation - curiosity. Sage had to know, and that was the big idea behind him - he called himself The Question and was always searching for answers. Sometimes he found them, sometimes he didn't.

From the start, O'Neil embroiled Vic Sage in the political scene of Hub City. The city's mayor, Wesley Fermin, was a corrupt drunk who was having his strings pulled by the Reverend Dr. Jeremiah Hatch, a quasi-religious figure. Yeah, the "evil holy man" was a little cliché, and O'Neil still feels a little regret about it.

"I had been a commercial writer for so long that I kind of automatically put in a number of commercial elements in the series," O'Neil said. "But when it came down to it, I chickened out and didn't make Hatch a 'real' minister. If I were to do it today, I wouldn't back away from it. He was the guy who was the brains behind the mayor, and quite corrupt. I'm now married to a minister, and I know how corrupt they can be."

Into the mix, O'Neil threw many memorable supporting characters - Aristotle Rodor, the brains (with a strong philosophical bent) behind the science that held Sage's Question mask on; Myra, Sage's girlfriend, who becomes the wife of the mayor, a move that awakens her own political aspirations; Myra's daughter Jackie; reformed policeman Izzy O'Toole, and henchmen like Jake and Baby, among others.

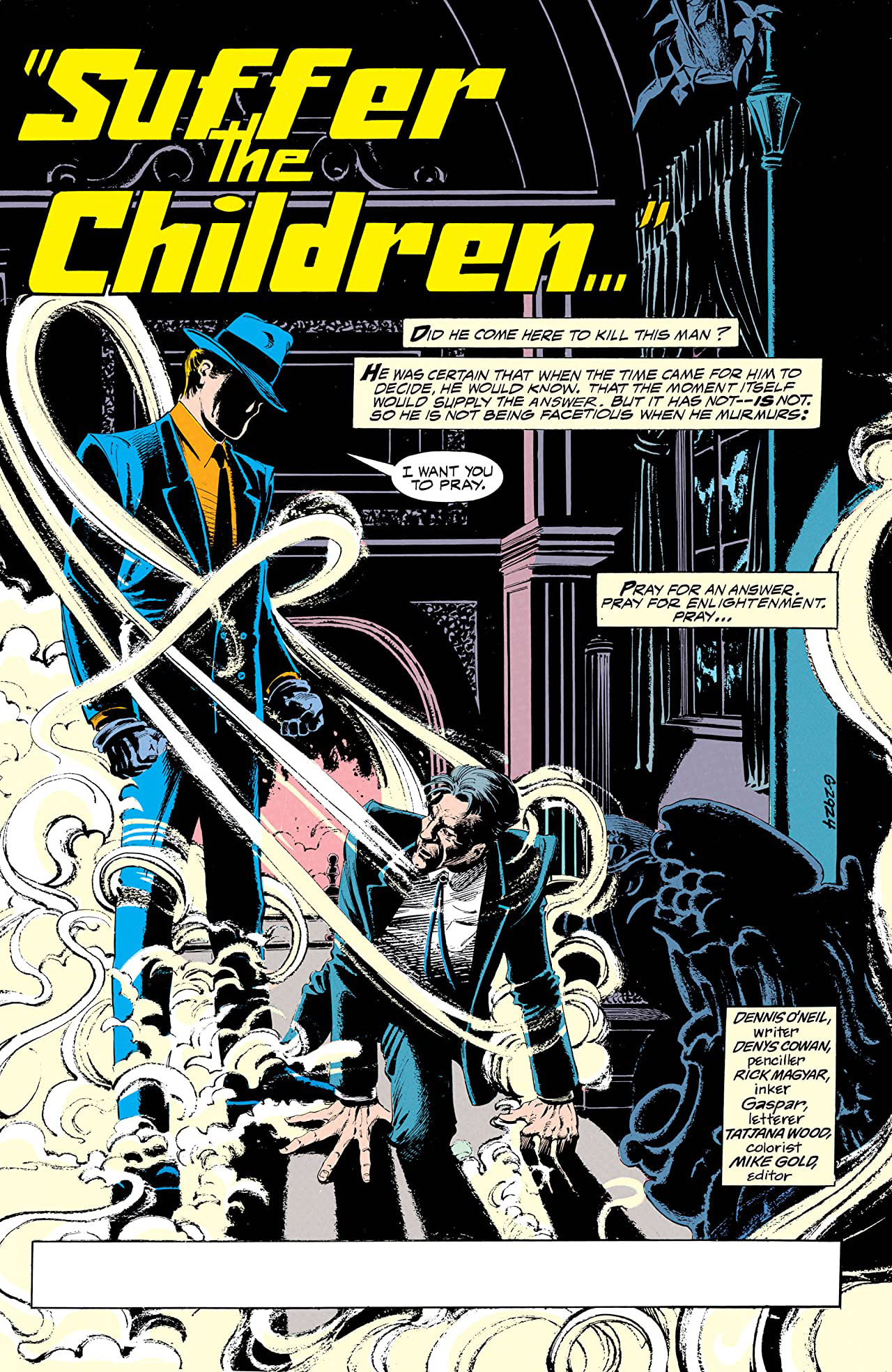

Throughout the entire series, Denys Cowan provided some of the best artwork of his career, adding dimension and realism when needed, caricature to the point of parody when appropriate. His fluid style meshed perfectly with O'Neil's flowing storyline.

As things in Hub's political infrastructure went from bad to worse, O'Neil examined social unrest on a city-wide scale and the ramifications of a city that's been plagued with deep corruption for years. While Hub City's political struggles played out mostly in the background, O'Neil did tackle smaller stories, such as a son who would do anything - anything to earn his father's love, the idea of revenge, pollution, and a trip to Santa Prisca where Dr. Rodor perhaps touched the divine. And that was just in the first twelve issues

To call The Question eclectic was an understatement.

But more than that, it was a chance for O'Neil to explore concepts that were interesting to him, from Zen philosophy to the mixing of science and religion to civil rights and social issues.

"It became more and more a place to experiment as time proceeded, both in terms of execution and content," O'Neil said. "It gets a lot more credit than it deserves for being a Zen book. I didn't know very much about Zen at the time, but I was really interested. When I went back and looked at some stuff recently, there's more of it in there than I remembered. But it also allowed me to set challenges for myself, like doing a story with the hero buried up to his neck in the earth for 23 of the 24 pages [issue #14] and see if I could bring that off - a story, virtually, without action."

Throughout the first year of the series, O'Neil infused the series with Zen ideas, from the story of the man who couldn't remember if he was a man dreaming of a butterfly or a butterfly dreaming he was a man to the eternal question of what do you do if you notice a ripe strawberry growing out of a cliff that you just happen to be holding on to for dear life. The answer, of course, is to eat the strawberry. It was a wild, experimental book, a showcase wherein readers were privy to the thoughts and interests of a '60s radical who was entering middle age.

And O'Neil was gung-ho to keep experimenting.

"The longer we got into it, the more of those things we tried. At one point, a question arose if we were going to make it an adult book and put an advisory on the cover. There are two stories out of the run that I wouldn't want a child to see. Most particularly when the kid mutilates himself to win his father's love. I voted in favor of putting some kind of parental advisory on the cover.

One of the places where big liberal me parts company with some of my liberal colleagues is on that question. I think we owed the parents a warning shot. Ultimately, it is the parent's responsibility to know what their kids are looking at and beyond that to know their own children well enough to know what will disturb this particular boy or girl. Having said that, parents don't have all the time in the world. They get busy, they get distracted, so it doesn't seem to me to be violating anything within a hundred miles of the First Amendment rights to just ask the parents to look at something before they let their kids go off and read it. Maybe it's fine, but at least have a look."

The idea that kids may have been reading The Question strikes fans of the series as more than a little odd. While the series did have its share of action and adventure, the overall themes probably weren't too interesting to anyone say, younger than eighteen - or at least an advanced 16-year-old. It was O'Neil exploring and asking questions, with zero spandex in sight. For some readers, the series was the first introduction to many philosophical ideas, and in some cases, spurred readers to further exploration on their own, aided by O'Neil's recommended reading list that appeared in the back of each issue.

One of the more philosophical topics the series tackled was the fact that Vic Sage could not have given less of a damn if someone knew who he was under that mask. Whereas Batman and Bruce Wayne are two different identities, Vic Sage and the Question were the same man. The faceless mask was just Vic's work clothes that he wore so he wouldn't be immediately recognized. In superhero-ese, Vic didn't have an alter ego. The man under the mask was the same as the man with the mask on. The mask just allowed him to do certain things.

"The dynamic of the double identity symbolically portrays the liberation of the god within all of us," O'Neil said. "We all, to some extent feel that the outside doesn't do us justice - for example, I may look like an ectomorph, but really, inside, I'm a hero. That's the appeal of any double-identity character, and we consciously decided to do without that and see if we could go in another direction, so Vic didn't have an 'alter ego' so to speak. His friends knew he was the Question, and many people found out that he was the Question during the course of the series. We never made a big deal about it."

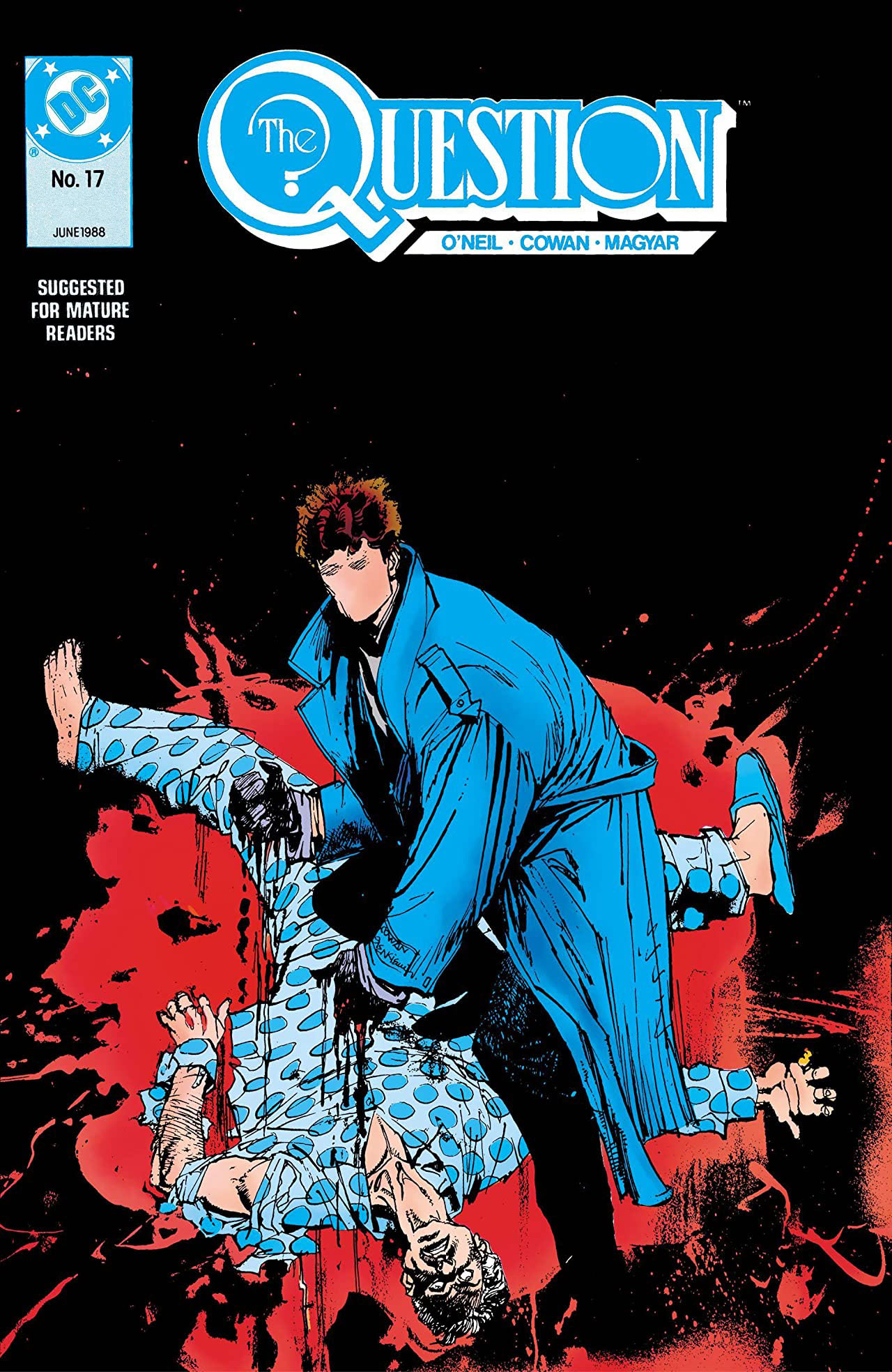

Throughout the series' second year, O'Neil continued with smaller stories while the politics of Hub City continued to evolve, and Myra eventually ran for mayor. Highlights of the second year of The Question included issue #17's homage to Watchmen (wherein Vic found an affinity with Rorshach, who was, in fact, an Alan Moore-created analog of The Question); a team-up with Green Arrow; biker gangs, sideshows, and a surprising culmination to the mayoral storyline, with a surprising twist for one of the supporting characters.

"I didn't know when I started out that Myra was going to be anything other than a very incidental character," O'Neil said. "Unlike Batman and his pretty celibate lifestyle, I wanted Vic to be somewhat normal. So, it was logical to give him a girlfriend, and at first, I didn't see Myra as much more than that. But somewhere along the line, it became an example of the old cliché of a character taking on a life of her own - Myra became to me, the most interesting and heroic person in the series, which wasn't at all what I started out to do with her - especially when she decided to run for mayor. I really, really liked and admired her at the end, even though she began her role as a walk-on."

The series continued for a year longer, allowing O'Neil to wrap up some loose threads and bring everything to a logical conclusion. "A 36-part story," as O'Neil called it. "It came to its closure, and that's where we ended that volume of it."

Shortly after the series ended, The Question returned for five issues of The Question Quarterly, which allowed O'Neil to let Vic stretch his legs a little more, as well as follow up on logical extensions of stories from the first thirty-six issues.

While the Question has made spot appearances in the years since it was the Rucka-written Cry for Blood that returned Vic Sage to his O'Neil-inspired roots. Coming up later, Rucka will write a Question back up series in Detective Comics, and O'Neil, for one, couldn't be happier that the Question is in Rucka's hands.

"I have unalloyed respect for Greg as a writer," O'Neil said. "I liked his stuff even before we met. Since then, we've had talks about what The Question meant to him in college. That series was one of his introductions to comics when he was in school."

But given his philosophical and Zen bent, O'Neil is content with the fact that things change, and that Rucka's version of The Question won't be entirely the same as the version he wrote. "His take on it will not be entirely mine, but that's okay - in fact, that's desirable," O'Neil said. "No one wants to read a carbon copy anyway, and he shouldn't - why go for second rate O'Neil, when he can do first-rate Rucka?

"So yeah, it's nice - both that Greg is handling the character, and that years later, people still look back fondly on the series. I guess I can't ask for anything more than that."

Matt Brady was the co-founder and managing editor of Newsarama until 2008. Since then, he’s moved back to science and teaches high school physics and chemistry. He’s also written a handful of comics, as well as The Science of Rick and Morty from Simon and Shuster. With his wife, Shari, he started thescienceof.org, which blends pop culture with science as a means to increase student engagement and the public’s interest in science.