Royalties? Contracts? Who owns what? Following the money for creators and their creations in comic books

Cash flow in the comics biz is a winding path through the worlds of contracts, IP, royalties, and more

The 'starving artist' may seem a romantic notion; the solitary, me-against-the-world Bohemian willing to sacrifice all monetary gain to preserve the integrity of their work.

But at the end of the day, who really wants to starve?

Comics, like most artistic enterprises, is also a commercial enterprise. And without some cash to fuel the furnace, there ain't much burning at the end of the pencil.

Don't get it twisted—most people working in the comics biz are happy to be there. You do get to fuel a creative fire, and the dress code is pretty lax, besides. But without a biweekly paycheck or at least the hope—if not the promise—of some compensation down the line, who would really be doing this? The filthy lucre may seem filthy to some, but it's better than no lucre at all.

Because as they say at the Cabaret…"Money Makes the World Go 'Round."

The changing face

For the bulk of both the history and the volume of the comic book business, the monetary path was a simple one: You worked for 'The Man,' you got a paycheck.

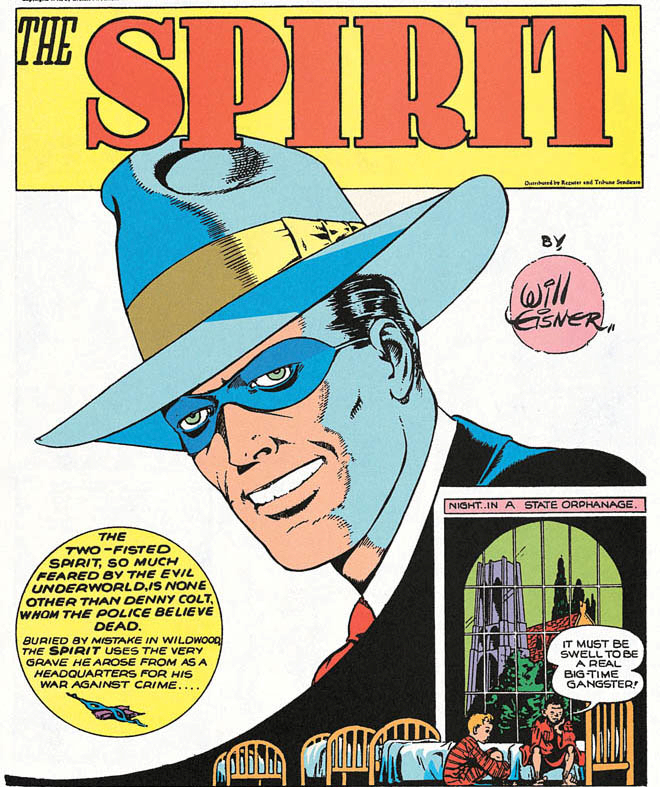

Large publishing companies employed talent to write and draw stories that the publisher owned, and that was that. Exceptions existed, and many were notable: Will Eisner always owned The Spirit, lock, stock, and barrel, from the character's inception in 1940. Gil Kane owned the rights to His Name is…Savage and Blackmark, his 1968 and 1971 graphic novels. And by the late '70s, creators such as Dave Sim (Cerebus) and Wendy and Richard Pini (Elfquest) were regularly sticking a thumb in the eye of the traditional model of company ownership.

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

But exceptions were just that - exceptions. When artist George Pérez got into the business in 1974, he did what most did. He took a gig at Marvel Comics.

"Pretty much all I ever expected out of comics was page rate," Pérez says. "You could make money doing sketches at conventions, and that could supplement your income. But page rate and some supplement, maybe, was all I ever expected."

Flash forward to modern times, though, and Pérez's cash flows are much different. The page rate and the convention income are still there - and the convention income is much higher. And there are royalties, intellectual property (IP) rights, and bonuses straight out of nowhere, never expected. The lucre can, and often does, flow to creators better than ever before.

Royalties

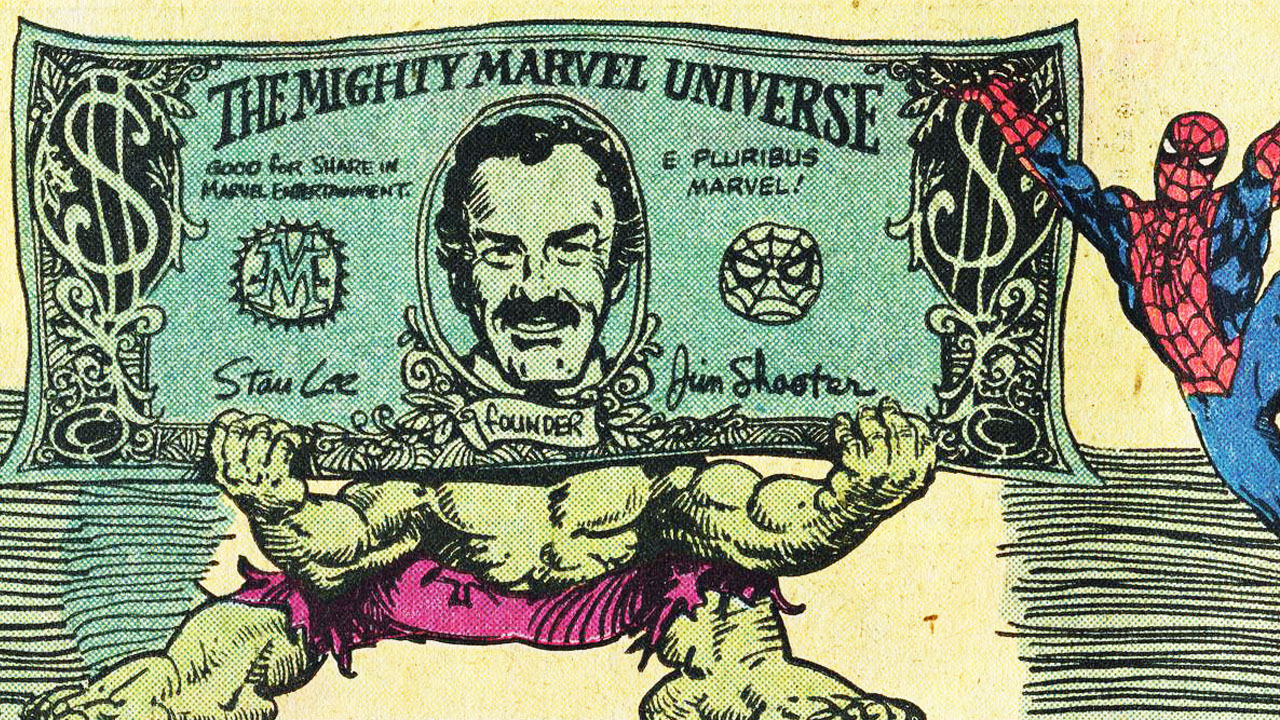

For decades, publishers begged off paying creator royalties, pleading that they couldn't afford to do so. But by the early '80s, competition for talent became intense enough that Marvel and DC finally relented, following a cue from smaller or previous publishers such as Eclipse and Atlas/Seaboard.

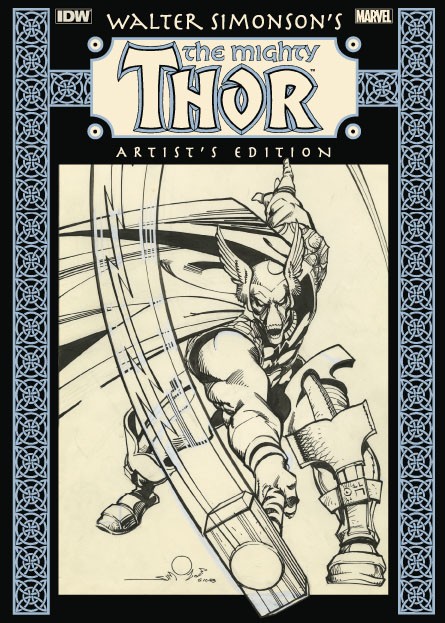

Today, royalties are a common and expected part of the talent compensation mix, provided sales hit a certain minimum level. Royalties can even pop up when things get repurposed elsewhere, such as when Marvel's Thor issues by writer/artist Walt Simonson were turned into Artist's Editions by IDW Publishing.

"I don't remember the exact percentage or the figure on that royalty," Simonson says. "My check came from IDW, because they had cut the deal with Marvel. But it was a couple of cheeseburgers for sure."

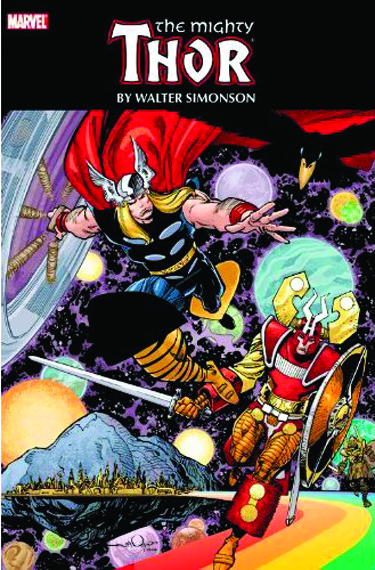

Royalties certainly can go higher. "I do remember there were some fairly handsome royalties on the [2011] Thor Omnibus," Simonson says. "That was a few steak dinners as opposed to cheeseburgers."

Royalties are, of course, pegged to sales. The higher the sales, the higher the royalties. These days, top-selling Marvel or DC books can add hundreds or thousands of dollars per issue to a writer or artist's bottom line. In the land-office business days of the early '90s when sales were reaching into the millions, royalties on single issues could reach tens of thousands or even $100,000+ for creators.

And once you've got it in writing, royalties can continue to pay off. It's not uncommon for creators with a long enough history and a popular enough body of work to be making 10%, 20% or even 30% of their income today off of material originally published decades ago.

"Work from 30 years ago that coughs up some money today is always nice," Simonson says. "Every trip to the mailbox has the potential to be Christmas."

Creators can also sometimes get an equity share in new characters they create. That was the case for George Pérez and Marv Wolfman when they launched The New Teen Titans for DC in 1980.

"Because several Titans characters have been used in video games, I've got royalty checks for six figures," Pérez says. "And I had no knowledge of this until I opened the mailbox, because I don't follow the video game world! So…wow! It's wonderful."

The gravy train might also roll when a name simply pops up. In their Titans run, Pérez and Wolfman turned Robin into Nightwing. That paid dividends when it almost happened in a movie as well.

"In one of the Batman movies, there was a scene where [actor] Chris O'Donnell was complaining that having a name like 'Robin' seemed a bit immature, and they just mentioned the name 'Nightwing' in the conversation," Pérez says. "Then I got a check—and Marv Wolfman did as well—for a nice, five-figure amount just for acknowledging the word 'Nightwing' and the character Dick Grayson would become. And that's one mention alone, not even half a minute of screen time."

Royalty and character equity programs vary from publisher to publisher and are still in a state of flux. Marvel just started sending out royalties based on digital sales, and DC's new program which became effective July 1, 2014, combines print plus digital. The conventional wisdom is that Marvel can reach higher aggregate sales (700,000 copies on Amazing Spider-Man #1 is nice!), but DC is hyper-detailed.

"DC seems to do a great and meticulous job in the accounting. I'll see that they sold five copies of something in Bolivia in a Spanish language edition…and here's a check for 14 cents," says Walt Simonson. "Marvel, you sometimes get a code that means nothing to you, just '82765X,' and $200. I have no idea if it was a toy somewhere, publishing, or whatever. But hey, it's all a nice bonus."

Contracts

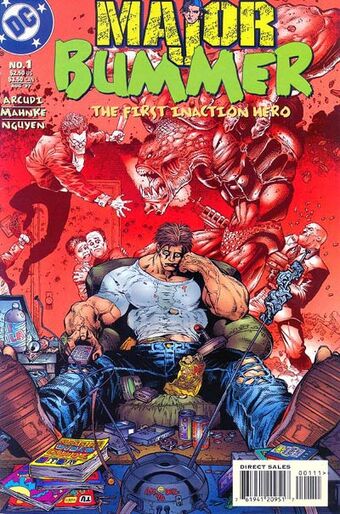

Of course, getting it right in writing is important. It's perhaps less important if you're the 183rd guy signing on to write Spider-Man for a year or two, but it's crucial when you're bringing your own creation to the table. Writer John Arcudi and artist Doug Mahnke brought the original property Major Bummer to DC in 1997, and the pair certainly made sure they had a lawyer in their corner.

"I call it prophylactic advice," Arcudi laughs. "What's the worst that can happen if you have a lawyer look at that contract and try to negotiate a better deal that gives you a better opportunity?"

Major Bummer was a critical success but never generated high sales. It was canceled after 15 issues, but Arcudi and Mahnke had the opportunity to take Major Bummer back.

"The deal with DC was that two calendar years after the end of the publication, Doug and I had a right to ask for it back. DC had a set amount of time to respond. They either had to pay me and Doug some money to retain rights, or they had to reprint it or use the characters elsewhere."

When that set amount of time elapsed, Arcudi and Mahnke got all rights to Major Bummer back. DC is generally reputed to be rather generous when it comes to such reversions, and a new Major Bummer Super Slacktacular was published by Dark Horse. All of which makes Arcudi very happy.

"The new collection made a profit," he says. "And more importantly, Doug and I sold the option on the movie rights to a number of studios over the years, and we've made more selling options than we did working on the book. That's where the money was on this one. The movie never got made, but we did alright."

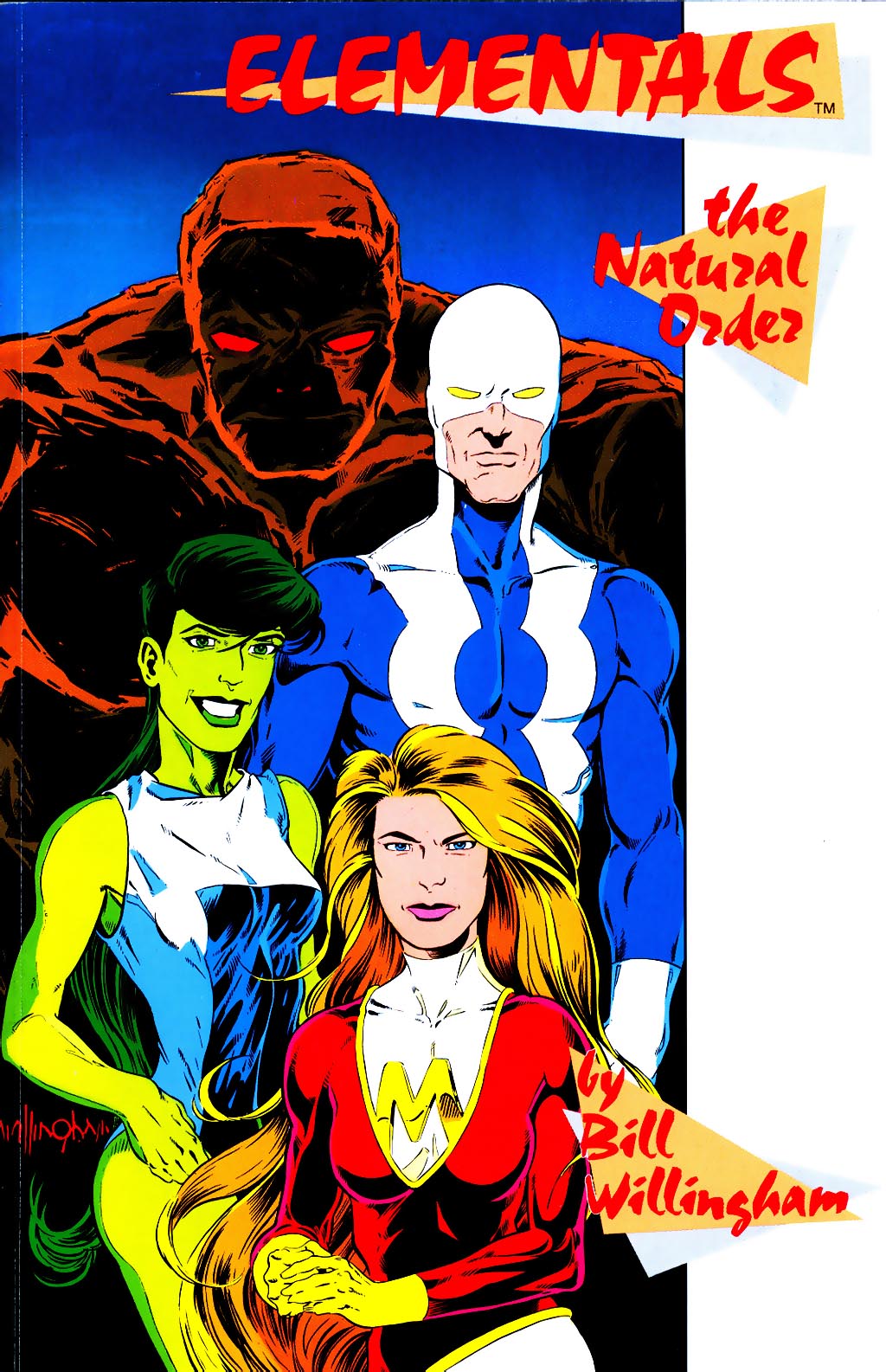

Every contract, however, is a give-and-take. Party X gets something, and in return, Party Y gets something else. Bill Willingham created The Elementals in the '80s. He sold the rights to Comico Comics in the '90s. And despite the fact that there are huge clamor and support for new collected editions or new stories of The Elementals, it's highly unlikely any will ever see the light of day.

"The rights to the Elementals are owned outright by a fellow named Andrew Rev [the former publisher of Comico]," Willingham says. "And he seems intent to not do anything with it at all, including selling the rights to people who come at him with bags of money. I cannot even guess as to what the inner workings of his mind are and his motivations in that. He seems intractable. These rights will never be available, the Elementals will never be collected, there will never be new issues. It's done."

Why did he sell? Simply put, Willingham needed the money at that time and place.

"It was money I needed. My future, as was the future of pretty much anyone coming out of Comico, was in doubt. Sometimes, a little bit of money sooner is much more important than a whole lot of money down the road. Today, I wouldn't even think of parting with the property for the amount I did."

Willingham is not bitter, and says his eyes were, and remain, wide open.

"It's a judgment call, and you have to live with it. I'm able to live with the fact that I made what was probably a bad deal. I am a capitalist. If you have an intellectual property, it has to include your right to sell it for money. You can talk about big, soulless corporations all you want, but they exist because people are willing to sell stuff for money. If you have a property and someone comes sniffing around looking at it, you have to calculate your costs. You have to look to the future. Can you scrape by and afford not to make a small deal early on, banking that better deals will be available down the road? It hinges on your ability to look into the future."

Working for yourself? Or 'The Man?'

Be it Elfquest or Elementals, Batman or Black Panther, many creators have the ability to pick and choose if they want to be in business for themselves, or work for a publisher that owns the IP. They can even bounce back-and-forth. Rick Remender is one such creator.

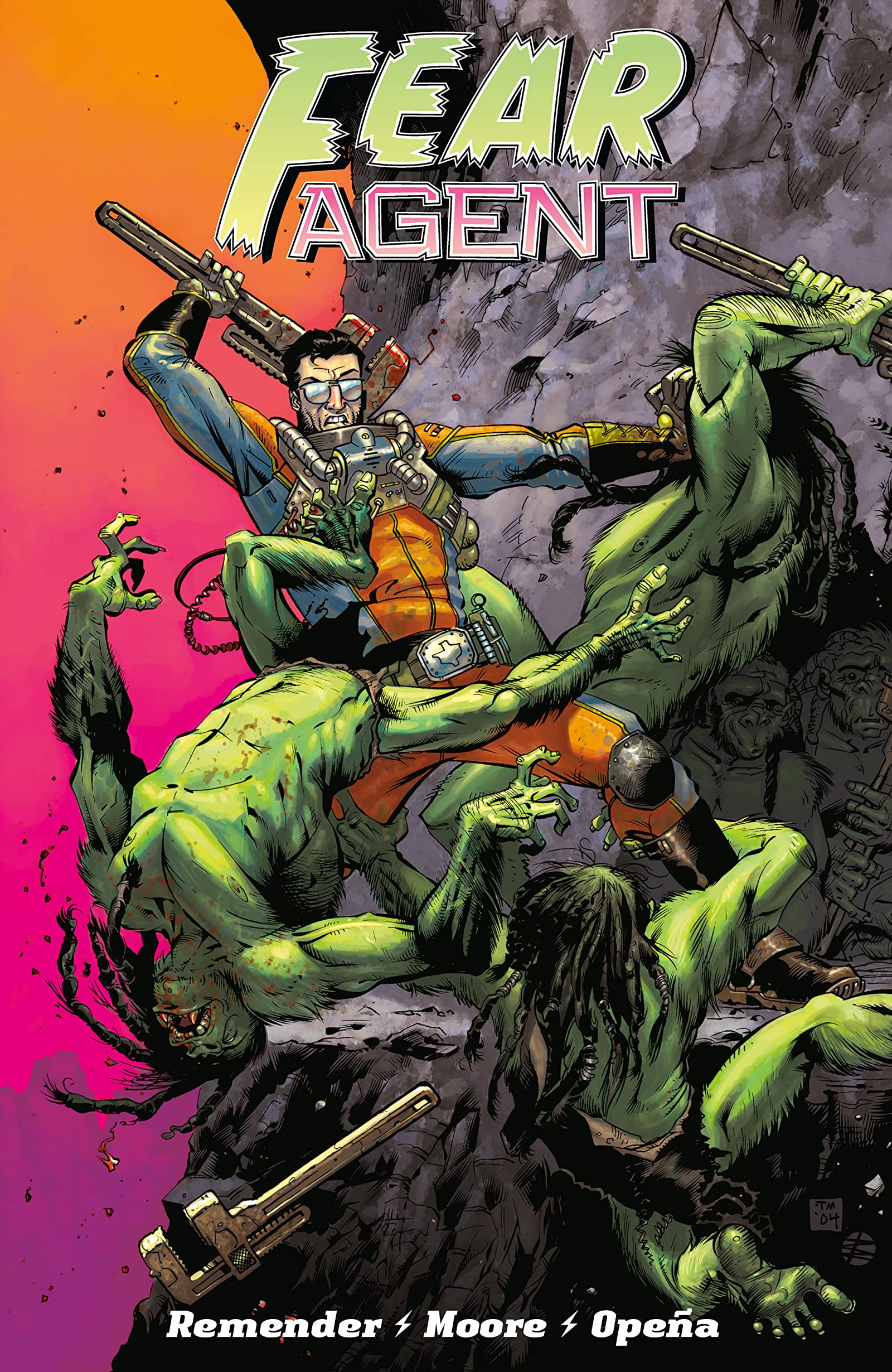

In the late '90s, Remender worked on and still owns an interest in the skatepunk character Black Heart Billy and the (*ahem*) scatalogically-inspired Captain Dingleberry. He went on to create Fear Agent, Doll and Creature, and more. But by circa 2009, Remender became a golden boy at Marvel, writing Punisher, Uncanny X-Force, and Venom, among others. He enjoys his ability to taste the best of both worlds.

"I stayed alive doing creator-owned for years," he says. "The Marvel stuff…I have more of it. If I'm able to do 2-3-4 scripts a month for Marvel, that's great steady income for me."

Still, Remender's back-catalog of creator-owned material is lucrative to him.

"On things like Last Days of American Crime, there was a lot of money that was made in the film stuff that's still creeping its way into production, and I was paid to write the screenplay on that. Now the numbers on Fear Agent are surging - we blew out of hardcovers that were $50 each."

Remender has seen readers' willingness to embrace more creator-owned projects.

"I think there's a shift in where people are spending their money," he says. "It kind of frustrates me, because from 1998 until 2010, I spent the majority of my time on creator-owned comic books. And at that time, the readership wasn't there. But now, people are moving to creator-owned books. I'm the man who peaked too early."

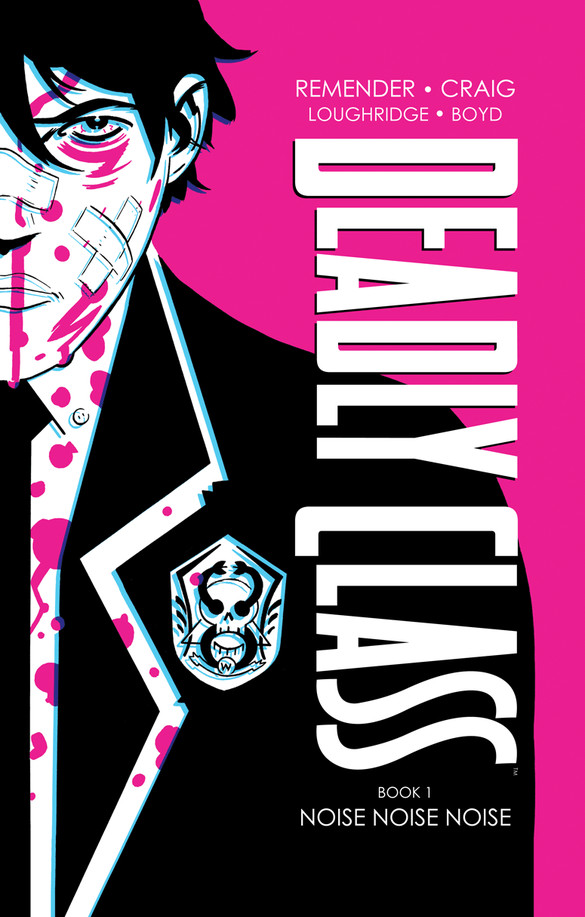

But Remender is creating a new peak. He recently launched Deadly Class and Black Science at Image to both strong sales and critical acclaim.

"I think the key now is to try and hit both areas at the same time," Remender says. "That's the upshot of my generation—we now have the opportunity to do both."

Joseph Michael Linsner does both as well. Linsner has primarily worked on his creator-owned Dawn over the years, and peppers in other self-owned projects such as this year's Sinful Suzi.

"I never thought I'd still be drawing Dawn 20 years later," Linsner says. "But one of my heroes has always been Frank Frazetta, who made sure he owned all the copyrights to his most important work. So from a young age, I always saw him selling prints of his own work, and I always thought it would be cool if I could do such a thing. And lo and behold, there are some Dawn paintings that I did in 1990 that I'm still selling copies of today."

But Linsner also takes time to do covers for Dynamite Entertainment's Lady Rawhide and the occasional Marvel limited series. He sees creator-owned as his bread-and-butter, and the other work as something that fills the gaps in-between.

"There are certain characters and properties that will stay alive in the public's imagination almost forever. I mean, how many years were there between Star Wars movies, while it still remained a juggernaut?" Linsner says. "For me, it seems the public has a short memory. I'll usually do Dawn for a while, then something else. When nothing new comes out, things definitely dwindle. But when a new Dawn book comes out, bwoom! That will bring new life to the old stuff as well."

Protecting your property

Ask anyone who owns a house: Ownership comes with responsibility and an expense. When the plumbing goes bad, you might have to spend a lot of time and money to fix it, but you have to protect your investment.

Brian Pulido has been protecting the investment called 'Lady Death' since 1991. The character has been published by at least four publishers, one of which Pulido owned and operated. Pulido still owns the character today, and the sometimes-bumpy ride has been worth it.

"Lady Death unto herself, the collectible portion and the licensing portion of the business, affords myself and my wife a very healthy middle-class lifestyle," Pulido says. "And that's not anything I could have predicted 20 years ago."

But the sexy/death imagery of Lady Death has proven perhaps too popular. Check out the back pages of L.A. Weekly or any alternative newsweekly in October and you'll see seemingly a million bars promoting their Halloween parties with swiped Lady Death art. Plenty of pickup trucks sport bootleg Lady Death stickers on the windows, too. Pulido spends a lot of time putting out the fires of misappropriated use.

"I think in two categories of infringement," he says. "One is what I call 'personal use,' or your own entertainment use. I can tell when a fan is just adorning his guitar for his own personal use or customizing his car, or painting Lady Death on the back of a leather jacket. I'm comfortable with those. It's actually because of a conversation I had with Gene Simmons of KISS many years ago. Gene said, 'Personal use keeps fandom alive.' And I agree."

But that's where Pulido draws the line.

"I'll come down on artists who do unlicensed Lady Death prints. I think it's unfair. It's not an intellectual property that the person owns, and I view it as taking money out of my household," he says. "There was even some lunatic who customized some mannequin into a Lady Death mannequin and was trying to sell it on eBay, and we shut him down. If you're using that likeness for capital gain, we're going to have a conversation about that."

The 'protection' aspect seems like it might be confrontational, but Pulido is careful to keep things as professional as possible.

"I've learned to be mellow and direct with people. Otherwise, the message gets lost," he says. "There are some people who do these things out of ignorance, but there are others who know better. Now I go in neutrally and assess the circumstances. But yeah, I go in to shut them down. And as a result, you don't see much at shows anymore. But eBay and the international markets are always an issue."

And sometimes, it's more than just the lucre

Bottom line, there are cash flows today undreamed-of by creators a generation ago. The money is nice. And sometimes, there's a nice feeling to go with it. William Messner-Loebs is a veteran writer with credits including Flash, Wonder Woman, Thor and much more to his credit. He's seen the same international royalty checks Walt Simonson speaks of.

"All these things would get anthologized and re-anthologized in South America, and right as rain, about once a year I'd get a check from DC for $300 or so," Messner-Loebs says. But there was a payoff beyond that for him.

Messner-Loebs always tried his best to really get into the heads of Brazilian characters he wrote, specifically DC Comics' Jaguar and Fire of Fire and Ice.

"I used to imagine people in Brazil saying, 'Who's this gringo, and what does he think he can tell us about Brazil?' But I'm told my stories of those characters were very popular there," he says. "Once at a San Diego convention, I was accosted by an entire Brazilian family as I was hustling from one panel to another. They told me they came to the convention specifically hoping to meet me. They kept calling me 'The Great Mr. Messner-Loebs.' I spent 30 minutes talking to them in the hallway. I missed the panel."

—Similar articles of this ilk are archived on a crummy-looking blog. You can also follow @McLauchlin on Twitter