GamesRadar+ Verdict

Scorn works wonders with Giger's and Beksiński's artwork, not only in terms of aesthetic fidelity but in creating a world that's utterly strange to exist in. This is a violent, painful, but fascinating place, thick with symbolism and interlocking puzzles that hint at some terrifying grand design. While it can be overly obscure and frustrating, especially in combat, Scorn serves up one hell of a journey.

Pros

- +

Stunning and provocative visuals

- +

Uses horror to explore intriguing themes

- +

Well-crafted multi-part puzzles

Cons

- -

Easy to get confused and lost at times

- -

Combat sections can be frustrating

Why you can trust GamesRadar+

It's rarely a good sign when you find yourself wandering in circles at the beginning of a game with no idea what to do. You start to worry that you've missed something crucial, and dread what the rest of the experience will be like if this marks the shape of things to come. So it was for me with Scorn early on, after it deposited me into a large cavernous area without a whisper of explanation.

Release date: October 14, 2022

Platform(s): PC, Xbox Series X

Developer: Ebb Software

Publisher: Kepler Interactive

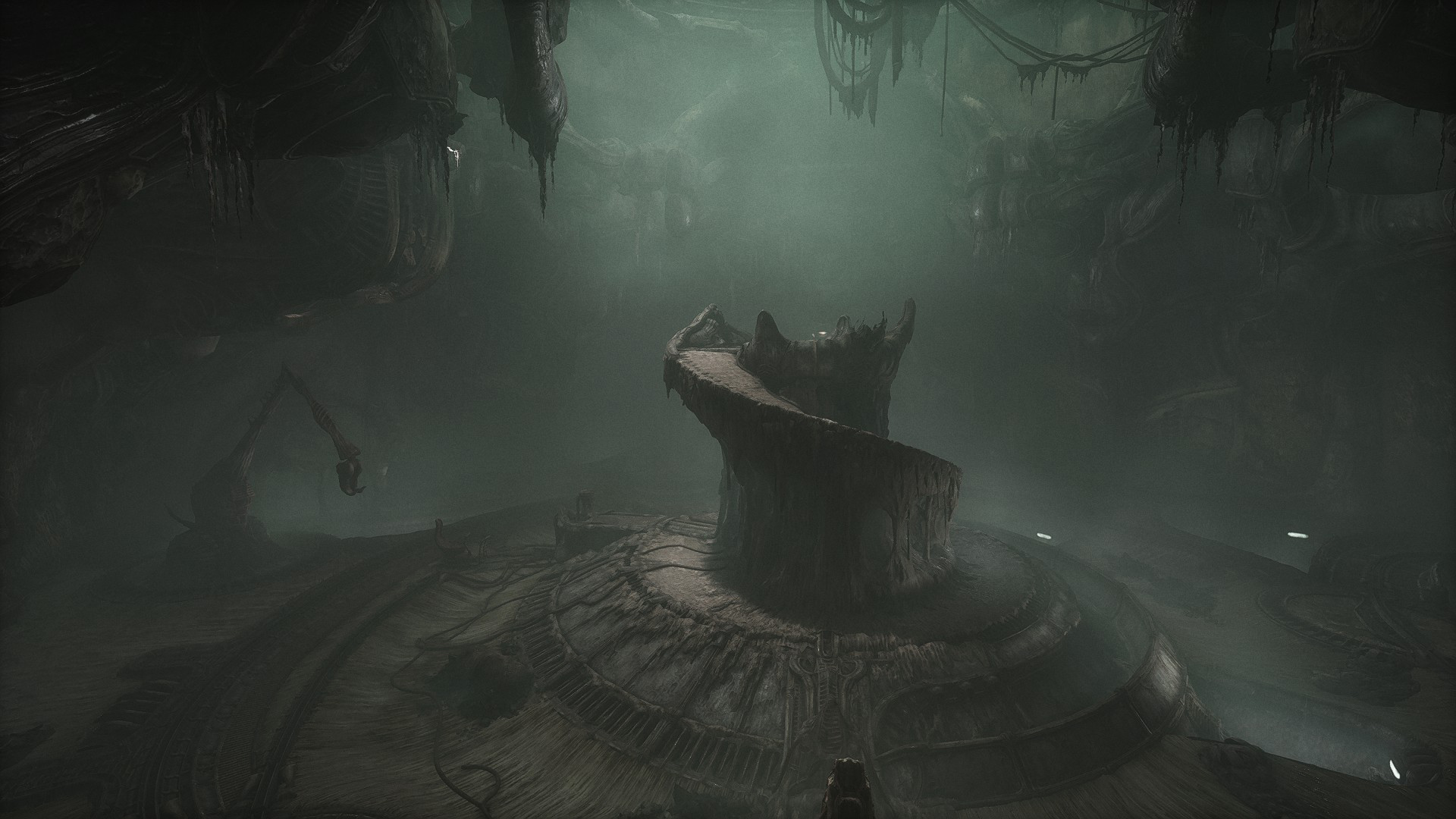

The center of this space houses a raised platform and a series of unusual contraptions that you can interface with, but none initially do anything useful. A selection of gray corridors snake off from the hub, some leading to further machines, before circling back. I surmised that the goal here was to force open a pair of great doors at the end of the cavern, but really it could have been anything. And while it turned out I was right about that, the path to getting them open proved torturously convoluted.

The good news is that I never got so stuck again. This first section is particularly bamboozling because it introduces so many unfamiliar concepts that have no obvious order (but also because a bug meant that one of the machines only worked with keyboard inputs, and I was using a controller). In the rest of the game, while the subdued color scheme can make orientation tricky, the level design tends to funnel you towards objectives, and narrows down the number of pieces in play at once. The opening of Scorn thus acts as a kind of unwritten warning to less committed travelers – gaming's version of the inscription above the gates of hell in Dante's Inferno: "Abandon all hope, ye who enter here."

Giger Counter

There is another reason for Scorn's obtuse start, though, one that's hinted at all over the walls of the caverns and beyond. From the first reveal of this first-person horror game, it's been clear that developer Ebb Software was inspired by the artwork of Hans Ruedi Giger, best known for his creature and ship designs on the film Alien. H.R. Giger's surreal airbrush paintings depict fusions of organic matter and machines in a way that doesn't translate into ordinary, rational experience, and everything about Scorn aims to sustain that otherworldly atmosphere.

Admittedly, the architecture on Scorn's unnamed planet mimics Giger's style to a point that feels near plagiaristic, but still, the effect is stunning. Scorn's washed out palette helps in blurring the lines between constructs of metal, bone, and flesh. Ominous protrusions flash back to the infamous Xenomorph's terrifying mouth within a mouth. Columns extend from ceilings like skeletal tarantula legs. In quiet moments, which are frequent in this slow-paced horror experience, you could be browsing a macabre art exhibition.

"Admittedly, the architecture on Scorn's unnamed planet mimics Giger's style to a point that feels near plagiaristic, but still, the effect is stunning"

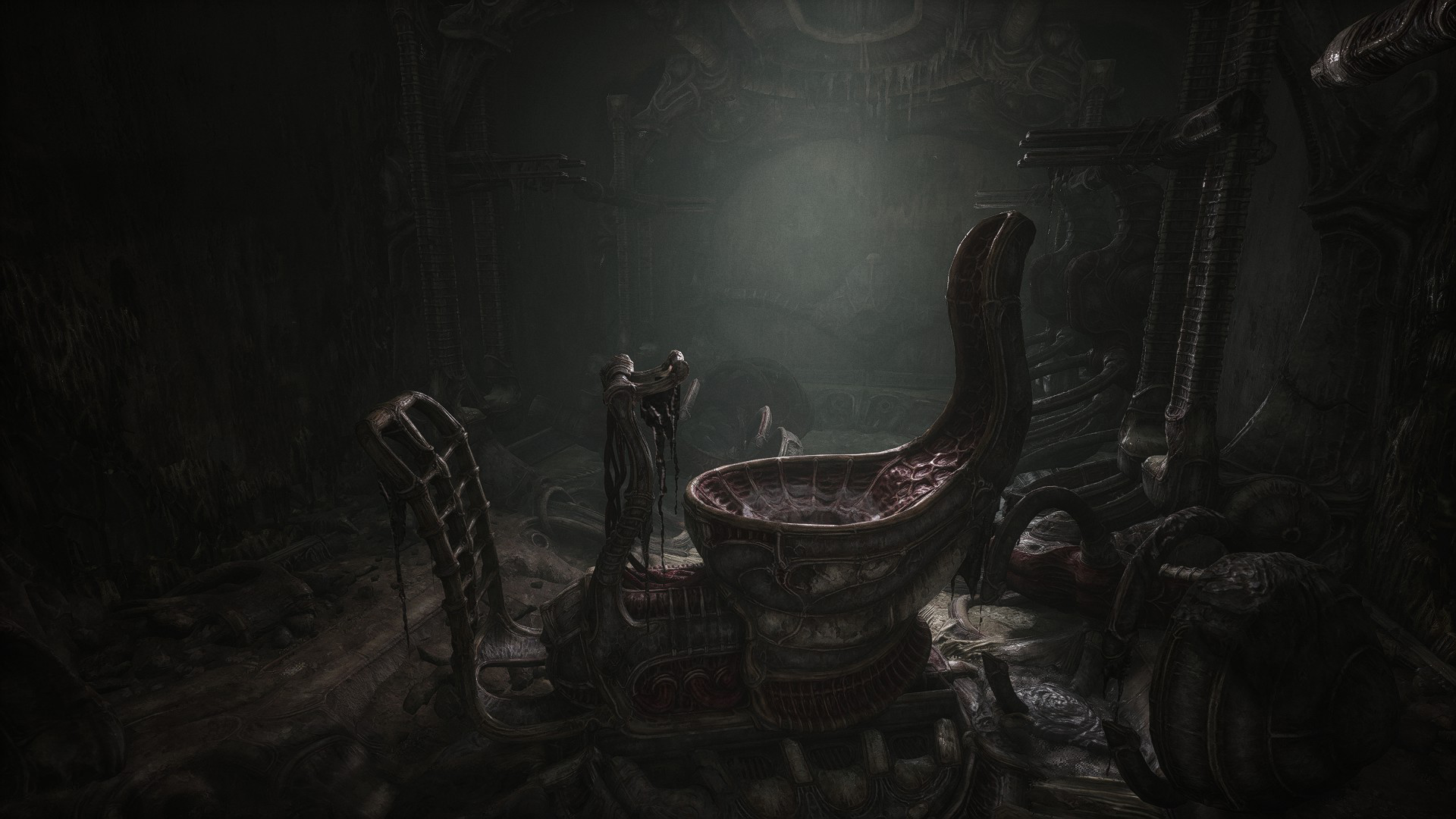

However, these aren't mere frescos, and Scorn's environments are equally full of texture. As a first-person experience, you mostly only see the hands of your character, and the camera likes to savor manual actions, imploring you to imagine the sensations. Switches are pulled by inserting your fingers into a row of fleshy, squelchy holes, for instance, then pulling down, stretching the warm outer skin. In many other cases, you end up with blood on your hands, literally as well as figuratively.

The putrefying visual feast is not merely a photocopy of Giger's work, then, and because of that Scorn captures the sense of a place that's truly alien – in that nothing here chimes with our social, linguistic, or technological touchstones to bed us into its reality. Whereas in most games, extraterrestrials are either monsters or humanoids with oddly shaped heads and concerns much like our own, Scorn's 'alienness' is incomprehensible, like that in Stanisław Lem's Solaris or Denis Villeneuve's Arrival, and its wordless opacity is part of the effect.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

No Pain, No Gain

Even the main character is largely impenetrable – a being that's sort of (but not quite) human, offered without name, identity, or backstory. The first thing you encounter before the cavern is a terminal with a protruding tube, glowing to show you can interact with it. Do so and the protagonist plunges their left hand into the tube, apparently unfazed by the prospect. It clasps shut around their arm, and with crude surgery, implants the limb with a mechanical device before letting go. Clearly this hurts, but now you have a tool that can access other terminals. Did your avatar know this would happen? It's hard to say.

This scene also establishes one of Scorn's inescapable themes – that progress, and life itself, is intrinsically coupled with pain. Opening those big doors in the cavern, for instance, involves sacrificing some poor unfortunate creature who may not have been so different to you, and every step forward from there is met with murder and mutilation. This place, whatever it may be, is fuelled by blood, in a way that presumably made perfect sense to whoever used to live here.

And someone did. You are after all surrounded by signs of 'civilisation', not only in the grand architecture but also in the piles of bodies you soon discover. This is where the influence of another surrealist artist, Zdzisław Beksiński, makes itself felt. You might also notice it on occasions where you venture outdoors onto a dusty planet surface painted in hot pastel reds and purples, but it's most prominent in the compositions of death and decay littered throughout your odyssey.

Fascinating here is how Scorn pulls together Giger's concepts of unconventional reproduction with Beksiński's explorations of the life and death cycle. There's a sexual aspect to Scorn's world, with phallic and yonic structures hard to miss, but it's far from erotic. Rather, like Alien, copulation and reproduction appear horrifying in themselves, transcending our notions of biological sex, species, and organisms. You see creatures born from plant-like seed pods, some created only to enable others to live. Umbilical pipes connect life to inorganic matter. Parasites latch onto hosts, sucking at organs to nurture themselves. It's vile, but nevertheless part of an alternate 'nature', one you simply can't understand.

Gross Point Blank

In fact, the bigger picture behind this system will never become clear, but working out how the individual parts function is often motivation enough, and ultimately Scorn's mechanics are anchored in our own gaming reality. In that first cavern, the concept of a door and a switch-based lock is familiar, even if the mechanisms aren't, while a machine that might have been anything from a toilet to a torture device turns out to be a kind of rail cart. Translating the twisted designs into more conventional gates, lifts, and levers is part of the fun here, and puzzle pieces usually reveal themselves to be neatly arranged once you make the required leap.

The same process applies when you pick up new equipment. For instance, that pulsating gadget in your hand may not bear any resemblance to a key card, but it still works like one, while a bone-shelled mass of wriggling pulp that could have escaped from a David Cronenberg movie turns out to be a weapon. Once the latter is in your grip, the middle chunk of Scorn thins out its puzzles to accommodate battles against an infestation of lumbering flesh sacks. At first, your firearm is more akin to a handheld pile driver that pumps out a metal rod, forcing you to engage enemies up close. Eventually you can switch that out for a shotgun appendage, then a powerful cannon, although ammo is scarce for both.

Encounters are more survival horror than FPS, then, with individual monsters capable of causing big problems. Sadly, as much as that suits the context and adds some tension to your exploration, the logistics of fighting are unreasonably cumbersome. Slow movement, tight spaces, and uneven scenery often combine to provide little means to avoid projectiles and plenty of opportunities to snag on jutting furniture. The weapons, meanwhile, are hefty and slow to recharge so each shot has to count, but it's hard to judge their effective range, so you might charge forward and leave yourself exposed as an assault fails to connect. Maybe the intent was to emulate the clumsiness of using such strange tools, but that would be a generous interpretation of Scorn's weakest systems.

It is worth persevering, however, into an engrossing final act that dials up the body horror to a degree that would satisfy Giger's Xenomorph itself. Yet even more notable is that, when presented with one last grand, multi-part puzzle, you should no longer feel bewildered and lost. Rather, confronted with new forms of bizarre machinery, you barely blink. They even make a perverse kind of sense. While you still have little idea about the higher powers at work behind Scorn's world, the links between its pieces have become perfectly logical. The confusion and frustrations dissipate as you realize you've slowly but surely assimilated into this horrifying existence, and perhaps that was the purpose all along.

Scorn was reviewed on PC, with code provided by the publisher.

More info

| Genre | Survival Horror |

Jon Bailes is a freelance games critic, author and social theorist. After completing a PhD in European Studies, he first wrote about games in his book Ideology and the Virtual City, and has since gone on to write features, reviews, and analysis for Edge, Washington Post, Wired, The Guardian, and many other publications. His gaming tastes were forged by old arcade games such as R-Type and classic JRPGs like Phantasy Star. These days he’s especially interested in games that tell stories in interesting ways, from Dark Souls to Celeste, or anything that offers something a little different.