"Cibele and How Do You Do it? have caused me to reflect on the rampant shaming of people who make games that are 'confessional' or who are seen to be 'over sharing' when they talk about things that are considered private, like sex," said game creator Nina Freeman, speaking as part of GDC 2015's Indie Soapbox.

It was a moment that, in many respects, thrust the young artist's voice onto the global stage, as she delivered a message that was as empowering as it was important – as relevant today as it was in then. "This stigma against honesty makes it hard to share straightforward autobiographical games; it's scary, being publicly shamed is not fun. However, I'm not going to stop making games about my own life experience. You can slut-shame me, you can call me an attention whore, and you can call me desperate; I don't care. I'll make games about my personal life because I want to. Games can and should be about anything."

This is a moment that I have often found myself returning to and reflecting upon over the years. It felt like a call to arms for a new generation of game makers. Those inspired by the experimental works that were arriving on the scene, compelled to take it a step further and release work that could transform the medium into a place where games that offered honest reflection, societal criticism, and personal anecdotes could be embraced – taken as seriously as every other type of game experience out there. Nina Freeman has a poetic approach to game design and a punk attitude towards execution; her work has proven to be as engaging as it is disruptive, and through it all she has made the personal playable.

Making the personal playable

To her fans, Nina Freeman is proof that bold, independent, artistic video games can be created in an industry that has had a tendency to disavow anything but violence. To development outfits like The Fullbright Company – the studio renowned for exploring the curiosities of the human condition with titles such as Gone Home and Tacoma, where Nina spent years of her career honing her craft before returning to independent development – she's part of the new wave of digital auteurs. To a minority that dwell in the shadowy corners of social media, she's that woman who found success making video games about her sex life on the Internet. But as she has said time and time again, games can and should be about anything.

"'Write what you know'. That was something I was taught and value a lot as a writer. My interests as a writer ultimately lies in ordinary life stories because I know ordinary life – or at least I know my ordinary life," she tells me. "A lot of my focus has been on relationships, sex, and love because they are all really ordinary parts of life but in art have been made extraordinary in a lot of cases.

"But life can be messy and imperfect. I like exploring how people can have a lot of problems and what that means for them, I like how a story can just be about that. How someone messed up – because we all mess up all of the time. It's scary to admit that things can fail, or that they can be complicated, or that maybe romance isn't actually romantic in the way that we traditionally expect it to be... I find it interesting."

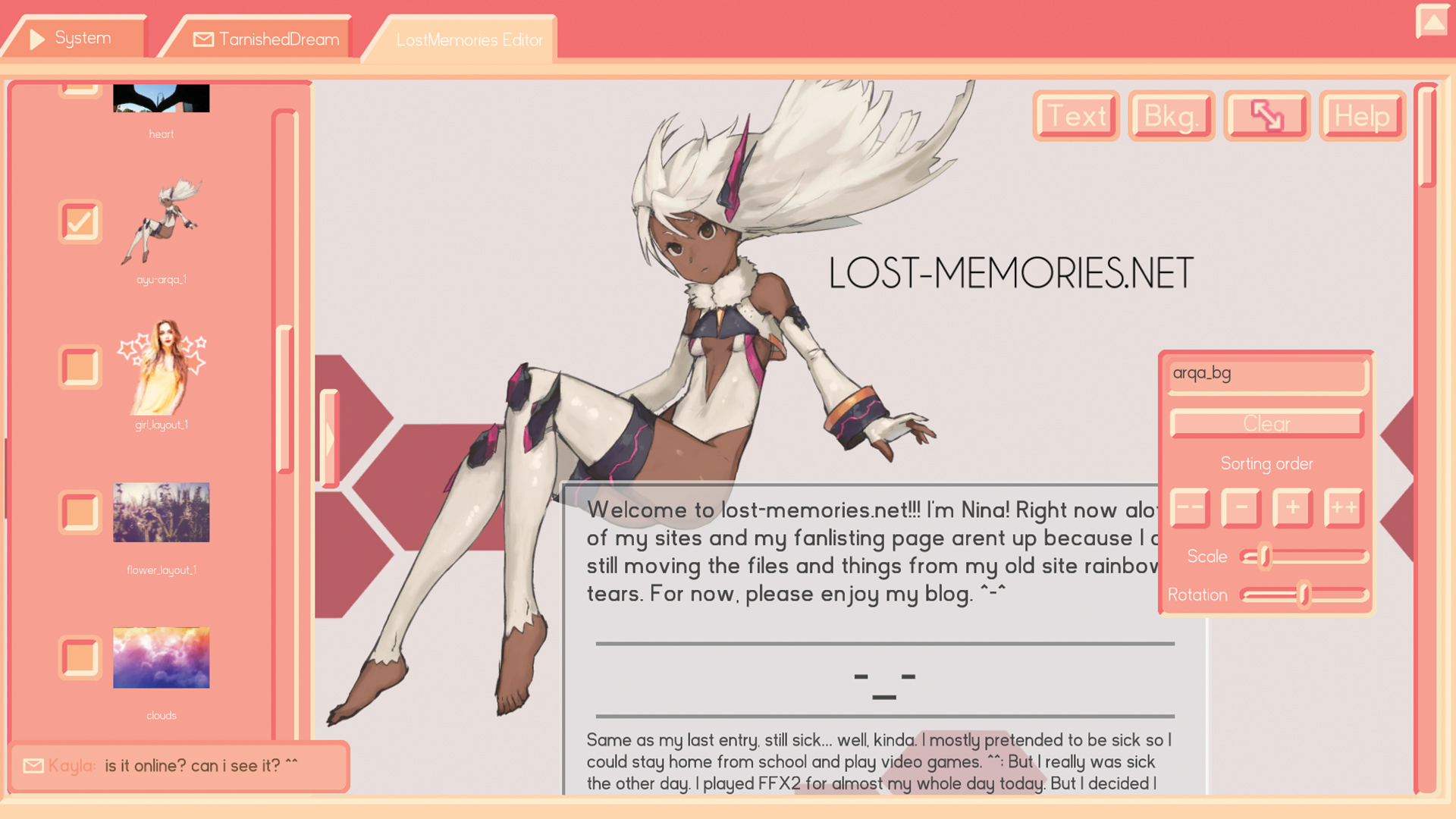

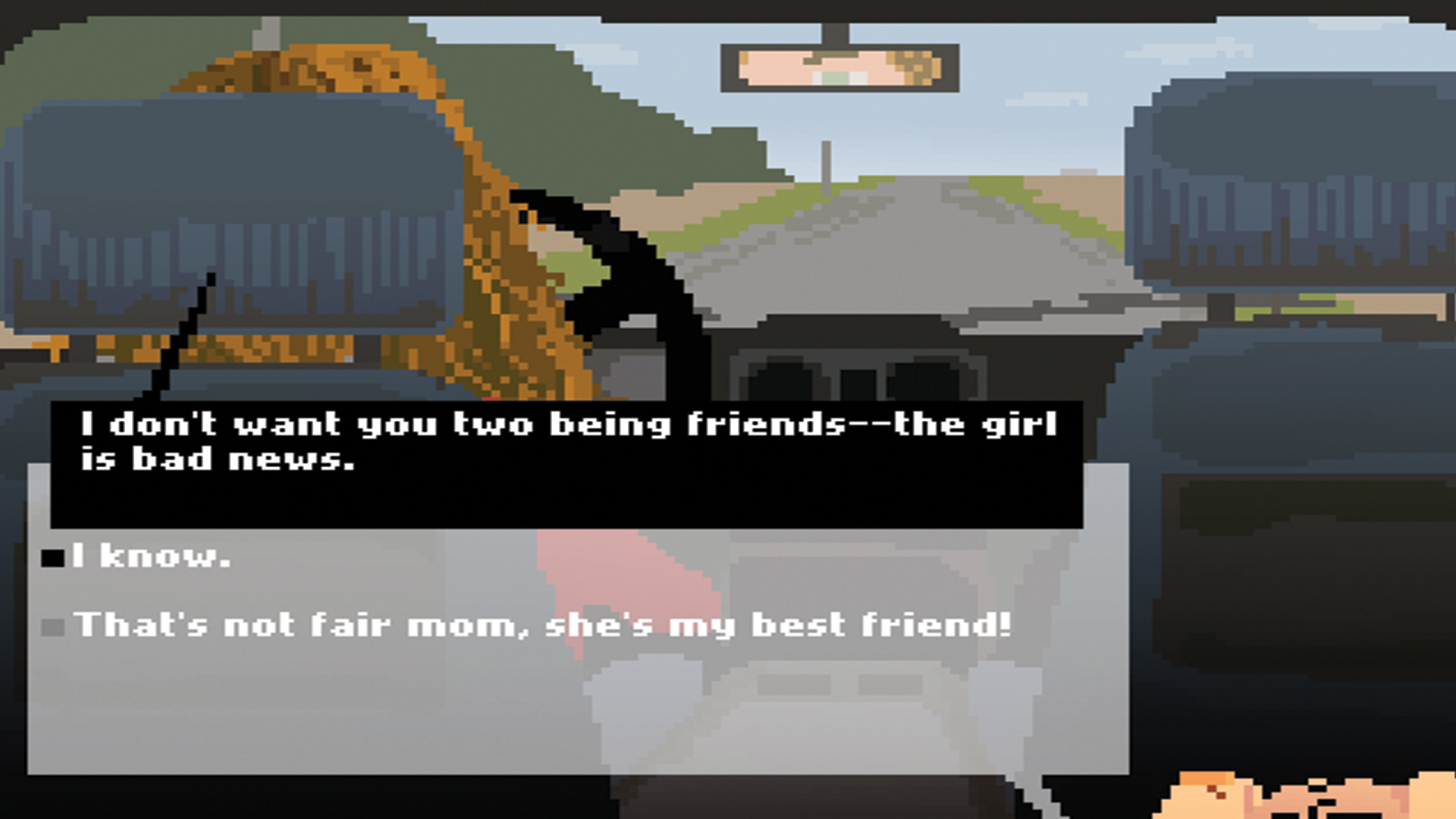

Freeman's games, 18 of them in the last seven years and each largely focused around honest autobiography, have made Freeman one of the most talked about developers of her generation. And yet she's still one of those rare creatives whose body of work is able to speak for itself. In these games – short vignettes, as she would call them – you often play as Nina, or, at least, a reflection of her, the story rooted somewhere in reality. This includes works such as Hokuto No Huchen (Fist Of The North Karp), based around a fishing trip with her father; Ladylike, which chronicles a series of trips to the mall with her disapproving mother; How Do You Do It?, in which we relive a childhood memory of smashing naked Barbie dolls together in the hopes of figuring out how sex works, an insight into the innocence of a young 12-year old girl that had been left confused by the infamous steamy car scene in the film Titanic.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Then there are her two most powerful works, Freshman Year, an unsettling exploration of a sexual assault from her college years; and Cibele, a game that unbashfully explores the nature of intimacy and sexual expression in online relationships – from the servers of an online MMO to an awkward bedroom fumble, Cibele doesn't pull any punches in its voyeuristic retelling of Freeman's 19-year old life experiences.

All of these intimate, narrative-driven video games are linked by an empowering energy and emotional pressure, by themes that reflect the mess and intrigue of daily life, using heartbreak and exploration of the self as the road to a better understanding. These games work, not merely because they are meticulously built, but because they are able to crack through social boundaries, because they are real – written with a clear sense of purpose and identity. They often act as a window into what is, for many of us, a different world entirely.

While they can have a tendency to be a stark and genuine reflection of Freeman's inner demons and desires, there's also purity to it all; a piece of each of us in each of them – we are but human after all. "I think that drawing on the small casual things we all tell each other about is pretty inspiring... I draw a lot of inspiration from casual conversation. I love listening to other people's stories, it could just literally be at the bar; if someone references something weird that happened to them, I'm always the person that will be like 'tell me more, actually tell me the story; the real story'.

"Ultimately," she considers, lingering on the thought for just a moment, "we are all storytellers, aren't we?"

When worlds collide

Freeman wasn't meant to become a game designer. She drifted through New York doing a bit of writing, pursuing a fading interest in theatre. She went to undergraduate college looking for answers, losing sight of the questions. Instead she found a mentor in Charles North, a second-generation New York school poet, who would inspire Freeman and help her see and think about the world in a different way. "This period of my life was really where I learned how to write and learned what I was interested in as a writer – ordinary life stories and vignettes, which, funnily enough, is what I'm interested in doing in games," she says, smiling. "What I learned from Charles North was that it's very powerful to write what you know and that you can really grasp something very honest and very genuine when you do. I really took that to heart."

It was during these years that she "met a group of game makers who invited me in to do game jams with them," she says, noting that she "kind of just fell into it all and found the similarities between our worlds as I went. I made that my way to fit into that world". It was their enthusiasm that would push Freeman to explore the booming indie market and mark her first attempts to bridge the gap between interactive entertainment and reflective poetry. "I think a lot of them were into my ideas because they were a little bit different to what they were doing. That went well for me," she says, laughing once again, her enthusiasm infectious.

"I remember being introduced to Gone Home, Dys4ia, Kentucky Route Zero, and Cart Life around this time. In those games I saw the type of writing that I enjoyed reading and creating in the poetry world. So I was like, 'OK, I love video games and I now understand that there is this commonality between my work and the work of these game makers'. I found a bunch of collaborators that were awesome who, luckily, wanted to explore these ideas with me."

But never did she think that making them for a living was an option. "I didn't really think I would be able to get a job in the industry, because I didn't think that what I was making would fit into what other people in the workforce were making," she says, laughing. Instead she poured everything into studying poetry, the writings of Allen Ginsberg, Frank O'Hara, and Elizabeth Bishop. The roots of Freeman's voice and work can be found here. "Much of their work is very much about putting something honest out there, that people can engage with. So, for me, I became comfortable with sharing my stories in that way – whether they are about a person or just stories about intimate things, because I am inspired by that body of work. Poetry taught me to care about small stories, so that became a passion of mine."

This would be something she would develop into her earliest works. My House My Rules in which you play as a young Nina trying to hide snacks around the house from her strict mother; Mangia, a text adventure documenting Nina's experience being diagnosed with a chronic illness, (one that gave her the time she needed to learn to program she will say, reflectively); and her first interactive experience, A Dating Sim, that explored the nature of consent, conversation and friendship in nightlife culture. These games are seen to convey a message too disruptive and unconventional for some corners of the Internet; too concerned with the self to be worth thinking about or paying attention to. That's something Freeman found strange as she intertwined her knowledge of poetry with her love of games.

"In the poetry world that's more of a thing, to be more open and personal. In games it is way more controversial. It's been interesting to come from a place where that was encouraged and something that I was always around to a world where it is less common."

It's difficult to understand why the games industry can be like this, so confrontational to anything brave enough to be different. We discuss it for some time, the controversies that have arisen over sex in games, the furore around any release that is daring enough to include some form of artificial relationship or sexual encounters. We laugh about a situation in which I was chastised by passengers on a train for playing Cibele – the sometimes-steamy FMV sequences apparently too much for some fragile British sensibilities. But this, she considers, is what happens when ordinary people are asked to consider and confront the nature of sexuality outside of the bedroom.

"One of the questions I get asked the most often is: 'sex is such a controversial topic in games, why do you address it?' I think part of it, for me, is that I grew up in an environment where talking about sex was just not allowed with my family. I never had a sex talk – even to the point where having a period was not explained to me until it happened. I thought that maybe my upbringing could have been an extreme, but I actually think it's pretty common for families of my generation to have been like that," she considers. "When I grew up and started making art and games, sex was something that I always had a lot of anxiety about discussing. So I started incorporating [sex and intimacy] into my work as a way of sort of learning how to talk about it, because I had always wanted to talk about it... after all, we want to talk about the things you aren't allowed to talk about, right?"

This, Freeman concludes, isn't just about sex, but part of a wider problem regarding self-expression and open dialogue in the world. It should be a theme, a natural part of life, that video games are as open to tackling as they are aggression and violence. But then there is, as she has said in the past, a stigma against honesty.

"Maybe [it is] selfish of me, but ultimately I'm creating work that I want to engage with and that I can use to express myself. I want to use my work to be able to talk about things that would be difficult for me to talk about otherwise. It's good, because I feel like I've been able to have a more open dialogue about sex stuff in my personal life [now], and in a culture where you just aren't supposed to talk about yourself," she says, clarifying, "that's not even just about sex, not at all. Talking about one's [own] life is perceived as something that is personal, or deemed inappropriate. I find the issue of those social boundaries to be pretty interesting."

Investing in human stories

This curiosity has fuelled much of Freeman's output, but it isn't designed to necessarily challenge or change people's perceptions of what is and isn't deemed appropriate. Nina is simply doing what she is trained to do, write poetry – she just so happens to express her thoughts and feelings in frames now, rather than clauses.

"This came up a lot when I released Freshman Year, which is about a sexual assault. Something I got asked a lot was 'is this an advocacy statement?' Well yes, in a sense. I think sexual assault is bad, and obviously that comes out in the game because it's a belief I have – I think that our beliefs are going to come out in our art, no matter what we do," she says, but that wasn't the driving force behind her decision to make the game. Instead, it was something far simpler. "I do want to speak about those issues, but for me, as a game designer, that was just a personal expression of a story that stuck out in my mind as interesting... it was an interesting way for me to experiment with player-character embodiment – the things that I'm interested in as a game designer."

"When I was first making games, I was doing a lot of it because it was cathartic or because I was still learning. But then, as I started to develop more of a voice as a game designer, and began realising that this was a craft and that I was really dedicating myself to it, it became more about... I recognise the kinds of stories that resonate with people, that get people engaged and talking, and I like to use them to explore the more craftsmanship and technical part of game design. Because I really am thinking about it as an art and not as if I'm trying to teach people about anything; I just want to tell stories."

These are stories that many in the development community, let alone the wider industry, would find difficult to tell. There would be a hesitance, of not only putting themselves out there on such public display, but of the self reflection that such a research, writing and design process would necessitate. But we get the impression that Nina isn't all that worried by what her games might reveal of her own personality to the world. It is, after all, part of being an artist.

"When I work on games that draw on my own life, I am always really deliberate about maintaining critical distance from the moment I'm looking back on. This is so that I can look at myself in my personal stories as more of a character than as myself. I'm primarily interested in writing an honest depiction of the character based on myself – always surfacing flaws, [the] good things and the bad things. I don't want to sugar coat anything, even when the work is based on my own life. I think honest, human stories are the most interesting, so I strive to always capture that kind of genuine feeling, [a] character who is imperfect, even when it's based on myself."

What's important now is that these types of games can move "beyond the enthusiast community and be part of a more global cultural conversation. I'm sure every medium has gone through this phase, right; every medium goes through its teenage phase, but now there is more work being produced and at a faster right by more people, by more diverse people, and games have been going through that for a while now. But we are finally starting to see the results of it... it's more a part of the games landscape as a medium than ever, it has found a legitimate place within it".

You can find, download, and play Nina Freeman's independent games on her official website and streaming fun games over on her Twitch channel.

This feature first ran in gamesTM 190, it has been republished and updated with permission. Photography supplied by Nina Freeman, credited to NashCO Photography.

Josh West is the Editor-in-Chief of GamesRadar+. He has over 15 years experience in online and print journalism, and holds a BA (Hons) in Journalism and Feature Writing. Prior to starting his current position, Josh has served as GR+'s Features Editor and Deputy Editor of games™ magazine, and has freelanced for numerous publications including 3D Artist, Edge magazine, iCreate, Metal Hammer, Play, Retro Gamer, and SFX. Additionally, he has appeared on the BBC and ITV to provide expert comment, written for Scholastic books, edited a book for Hachette, and worked as the Assistant Producer of the Future Games Show. In his spare time, Josh likes to play bass guitar and video games. Years ago, he was in a few movies and TV shows that you've definitely seen but will never be able to spot him in.