Originally presented in SFX 97

Alex Raymond, creator of a universe, was a dreamer with a death wish.

Perhaps the finest comic strip artist of all, he lost his life by gunning a Corvette on a wet Connecticut highway, racing the rain, racing to die. It was a demise stained with irony. Raymond dreamed until you feared his gift must burst - his visions were huge with colour and life, romances of rocketships and death rays, dragons and Hawkmen, Emperors of the Universe and Queens of Magic, all captured with a clarity that astonishes even today, as if he had personally witnessed such worlds and needed to preserve them forever.

Born in 1909 in New Rochelle, New York, the father of Flash Gordon was a graduate of the Grand Central School of Art, grafting on such newspaper strips as Tillie the Toiler and Tim Tyler. In 1933 he was approached by King Features, whose rivals, National Newspapers, had enjoyed huge success with Buck Rogers, a daily space opera created by Phil Nowlan and Dick Calkins. King craved their own high concept fantasy adventure strip to compete with National's 25th Century daredevil.

The first instalment of Flash Gordon appeared on Sunday, January 7 1934. America was dreaming desperately in the 1930s, building such kingdoms in the clouds as the Chrysler Building and dancing away the Great Depression with the dazzle of Hollywood chorus lines. The debut chapter of Flash Gordon showed a world where financial calamity on Wall Street was a mere sideshow, where headlines screamed "World Coming To End - Strange New Planet Rushing Toward Earth - Only Miracle Can Save Us, Says Science!'

That miracle was Flash. Raymond's first episode finds the "renowned polo player and Yale graduate" rocket into uncharted space with the beautiful Dale Arden and faintly crazed scientist Doctor Hans Zarkov. Their destination is Mongo, the 'Strange New Planet' ruled by a despotic Emperor, Ming the Merciless. Mongo is a cosmic Oz, populated with tribes of Tree Men, Monkey Men, Clay Men and Lion Men, a dream-logic geography of underwater lands and forest realms and ice kingdoms. Raymond's art was a pure headrush, but never feverishly so. A sublimely gifted craftsman, his exotic, flamboyant worlds were rendered with fine brush strokes, all grace and precision. Flash only saved the world on Sundays until May 27 1940, when a daily strip appeared, drawn by Raymond's former assistant Austin Briggs.

Universal Pictures acquired the rights to Flash Gordon in 1934, releasing a 13 episode Saturday matinee serial in 1936. The strip was popular enough to virtually guarantee box office success, and fantastical hokum had already fuelled such popular chapterplays as The Vanishing Shadow, The Lost City and The Phantom Empire. Directed by Frederick Stephani (who also wrote the screenplay) and an uncredited Ray Taylor, the serial found Mongo on a collision course with Earth, warping our gravity and pummeling us with meteors.

Sign up to the SFX Newsletter

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

Universal invested heavily in the crowd-pleasing promise of Flash, budgeting the serial at $350, 000, three times the usual cost of such pulp picturehouse fare. The large budget allowed for glass paintings, mattes and split-screen shots as well as a lavish set of Ming's throne room. The costumes worn by Flash, Ming and Barin were exact reproductions of Raymond's baroque originals, while all the clothes were made in colour, rather than the muted greys and browns that were the norm for black and white film-making.

Elsewhere there were economies. The serial borrowed both the crypt and the tower sets from The Bride of Frankenstein, while Ming's sinister laboratory was the redressed Transylvanian castle from Dracula's Daughter. An Egyptian idol from The Mummy was reincarnated as Mongo's great god Tao, while Zarkov's rocketship was a recycled miniature from 1930's flop SF musical Just Imagine. There could be no travelling mattes, rear screen projection or stop motion animation and the producers were denied access to Universal's famed miniatures department. And so cameraman Jerry Ash created the skyways of Mongo in an empty barn on the studio lot. Rocketships of wood and metal were lashed to spare microphone booms to fly past the camera, powered by pure resourcefulness and flurries of electrical sparks.

Larry 'Buster' Crabbe beat Jon Hall for the role of Flash. The former athlete had won Olympic gold for swimming in 1932 and initially saw Hollywood as simply a means to fund his law school ambitions. He traded his athletic fame for celluloid currency, stunt-doubling in 1932's The Most Dangerous Game before playing Edgar Rice Burroughs' jungle lord in Tarzan The Fearless. "A guy on another planet was a way out theme in those days," said Crabbe, smarter and more ambitious than the classic beefcake, "but still interesting enough to tickle the imaginations of adventurous souls. I honestly thought Flash Gordon was too far out, and that it would flop at the box office. God knew I'd been in enough turkeys during my four years as an actor; I didn't need another one. I was holding out for a DeMille, class A production."

Jean Rogers was cast as Dale Arden and shared her co-star's scepticism. "Buster and I both thought the whole thing was nuts," she recalled. "At the time, who could think of Mars and outer space and all that? I just thought that the public might say it was too incredible. I thought they were going to laugh at it and say, 'Well, isn't this silly?' It all seemed so hard to believe. I thought the writer of the serial had lost his mind!" Rogers had won a local beauty contest sponsored by Paramount and made her Hollywood bow with 1933's Eight Girls In A Boat. She established her serial queen credentials in Tailspin Tommy And The Great Air Mystery and Ace Drummond. Ming was played with huge, universe-enslaving relish by Charles Middleton, a familiar villain from Laurel and Hardy shorts. "He was a very nice guy, but he had to stay in character," Rogers remembered. "He strutted around like Ming. The minute he put on his street clothes, he was a different person."

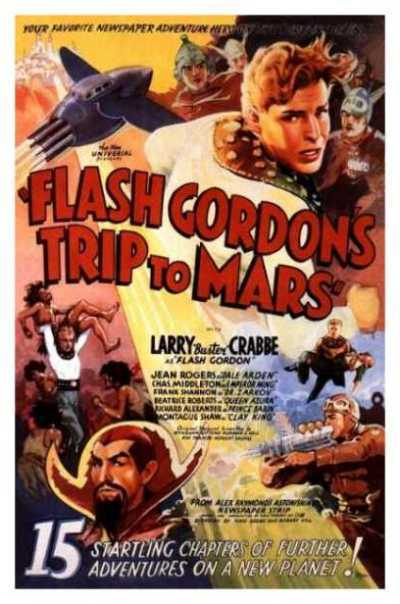

Shot on a rollercoaster schedule of six weeks, Flash Gordon was a box office triumph, so popular that it played to evening crowds as well as the Saturday matinee bubblegum set. It became Universal's second most successful film of the year, beaten only by Deanna Durbin's Three Smart Girls. 1938 saw the inevitable sequel, Flash Gordon's Trip To Mars, billed as "15 startling chapters of further adventures on a new planet." The tyrannical Ming was now allied with Azura, the Red Planet's alluring Queen of Magic, strafing Earth with a diabolical "nitron lamp".

While still costly by chapterplay standards, Flash's Martian adventure was produced for $175, 000, half the expense of the first serial. Ming was reduced to supporting character status but Middleton perfected a Mephistophelean sense of menace, adorned in a shadow-black skull-cap. Infra-red photography was used to enhance the alien atmosphere of Mars while a shot of a city-spanning bridge of light perfectly captured Raymond's heady sense of marvel. The serial was brutally edited to feature length and re-released as Rocketship before being rushed into cinemas again in a bid to ride the notoreity of Orson Welles' prank Martian invasion. This time it was opportunistically titled Mars Attacks The World.

Universal produced a third and final serial in 1940. Flash Gordon Conquers The Universe finds Ming blighting the Earth with a lethal plague known as the Purple Death, the antidote to which resides in Mongo's frozen realm of Frigia. While blessed with improved miniature work - and impeccable art direction that captured the majesty of Raymond's later strips - the last of the Flash serials is perhaps the least. "I didn't like it," said Crabbe. "We used a lot of scenes that we'd done before. Universal had a library full of old clips: Flash running from here to there, Ming going from one palace to another, exterior shots of flying rocketships and milling crowds. It saved a lot of production time, but I thought it was a poor product that was nothing more than a doctored-up script from earlier days." Flash Gordon Conquers The Universe was profitable enough to spark talk of a fourth serial, but nothing came of it.

In May 1944 Alex Raymond abandoned his galaxy to join the US Marines. Austin Briggs succeeded him on the Sunday pages, but never quite replicated the grace and quixotic imagination of his mentor. Raymond was a commissioned officer on an aircraft carrier and saw action in the Pacific. He left the navy as a Major in 1946 and returned to newspapers, creating Rip Kirby, a noirish police strip tuned to the gloomier, more violent times. He would never draw Flash Gordon again.

Raymond was gifted, successful, movie handsome and the creator of a genuine cultural phenomenon. On September 6 1956 he lost his life while indulging his lust for fast cars. He died instantly on impact, killed by a shard of a Corvette's wraparound windscreen. It was his fourth car accident in a month. He had been hospitalised three times. "He was trying to kill himself," believes fellow cartoonist and fateful passenger Stan Drake, who sensed a darkness and a disquiet in Raymond, perhaps precipitated by recent troubles in his marriage. It was a loss; "Of all the comic strip creators, he unquestionably possessed the most versatile talent," said Maurice Horn in The World Encyclopedia of Comics.

Raymond's enduring legacy was Flash Gordon, a space hero that conquered the universe, the Sunday funnies and the silver screen, a bloodline of imagination that gave us Star Wars and the modern science fiction blockbuster. Just ask George Lucas. "Originally I wanted to make a Flash Gordon movie with all the trimmings," he revealed, "but I couldn't get the rights to the characters."

His world-conquering tales of the Skywalkers are clearly in debt to the ray-gun fairytales of Alex Raymond.

Nick Setchfield

SFX Magazine is the world's number one sci-fi, fantasy, and horror magazine published by Future PLC. Established in 1995, SFX Magazine prides itself on writing for its fans, welcoming geeks, collectors, and aficionados into its readership for over 25 years. Covering films, TV shows, books, comics, games, merch, and more, SFX Magazine is published every month. If you love it, chances are we do too and you'll find it in SFX.