Silliness is gaming's best feature and one of its big limitations

"I have just smashed a dragon in the face with a church. In space"

That was how I responded a couple of years ago when a friend e-mailed to ask if Bayonetta was as good as it looked. She immediately understood what I meant. Because in gaming we can have conversations like that. We can matter-of-factly throw out such abstract descriptions of ludicrous events and know that, if our audience is savvy enough with game genre, they’ll immediately recognise it as naught but the highest plaudit. See also instances of chainsawing through the guts of a giant worm in Gears of War 2, or kicking a rocket-powered masonry drill up a boss’ arse in Bulletstorm.

I love that about games. They’re a medium utterly unique in the way that they can be flagrantly silly on the most extravagant levels while also remaining utterly cohesive as narrative experiences and mechanical structures. I think it stems from their origin as context-free playthings. Back in the days when the average game looked (and sounded) like the nappy contents of an unattended baby eating Lego, story was just there to add basic context to the act of manipulating the graphics. The blue blob? He’s a space ranger. The red blob? An alien. And that was fine. Games were formed of the basic interactions that developers could create. Everything else came afterwards.

Thus, story was a secondary consideration. Game design teams didn’t attract aspiring Nobel lit. prize winners, because they were a ridiculous medium to try to write for. Gameplay remained the dominant driving force of their content, and story remained a silly sideline. And over several decades, that seems to have developed into a culture of playful silliness in even the most serious of games.

Thus, a game like Bayonetta can contain serious moments of pathos, including one Hell of an existential downer towards the end, and not have any of it clash with its angel-punching, pole-dancing disco excesses. One of the most critically lauded, philosophically concerned action games of 2013 can seamlessly task you with fighting clockwork Terminators dressed like George Washington. Grand Theft Auto can tell a thoughtful parable of modern disaffection and the search for purpose via the medium of stoned hallucinations, geriatric celebrity stalkers and using the inside of planes as runways for smaller planes.

And that’s great. It makes games a richer, more dynamic experience, and it provides a stimulating, refreshing narrative tone that you just won’t find in any other medium. Because in any other media you just couldn’t make this stuff hold together. There’s an accepted unreality to the necessary game mechanics underpinning any video game--all regenerative healthy, 20 foot jumps, super-powered combat and gigantic guns with no respect for the laws of physics--that adds an implicit, abstract unreality to the game’s world as a whole; a sense that normal rules do not apply, so anything goes. That’s the reason that most video game movies fail to satisfy. You just can’t do most games in live action without them appearing ludicrous outside of their own context.

But as great as all of this is, I lately can’t help wondering if it’s hindering games’ perception as a medium out in the wider world. Speaking to Rock, Paper, Shotgun this year, journalist and games advocate Charlie Brooker hit the problem on the head.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

"My theory is that video games are like speaking Esperanto. Video game players are like people who learnt Esperanto years ago. We all learnt Esperanto. And there’s all these brilliant Esperanto-language films available, to use a metaphor. They only make sense if you know Esperanto, they don’t have subtitles – but they’re brilliant. And we keep telling people how good they are. But there’s this learning curve which is that you have to learn fucking Esperanto. Because you only have to sit down with someone who doesn’t play video games to understand how high the bar to entry still is"

Brooker was ostensibly talking about the internal rules of gameplay mechanics, but I think his sentiments can also be applied to the rules of game worlds and their narratives. While I’ve spent the first part of this article espousing the delights of gaming’s silliness and the openness with which we can discuss it, the key part of that second paragraph at the top of the page is the phrase "if our audience is savvy enough with game genre". Because I feel that games have becomes so much a product of their own unique workings that those workings are perhaps a little impenetrable to those who are becoming intrigued by games as an increasingly prominent medium.

After all, with the mechanical interactions of games still the highest barrier of entry to non-gamers, story is the most powerful tool we have for hooking in newcomers. Narrative is a completely universal language. All human beings understand it. Storytelling is how people comprehend and make sense of the very world around us. Without applying an implicit narrative structure to things, the world is just a collection of stuff happening all over the place.

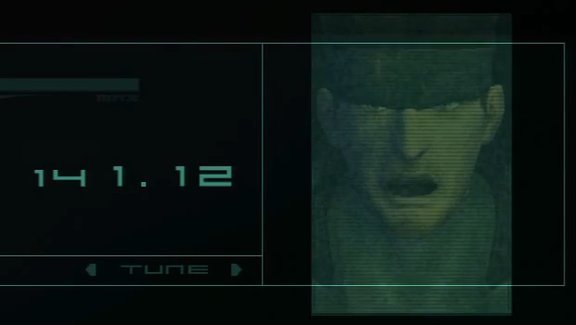

Some games have caught major mainstream interest and respect by leveraging that universality over the last year or so. The Walking Dead was a massive hit as a result of its focus on gritty, human interactions. Gone Home has been picking up accolades all over the place due to its grounded exploration of family drama. But ask more hardcore gaming advocates about the games that show our medium at its mature, creative best and they’ll throw out suggestions like Metal Gear Solid, Assassin’s Creed, and the recent work of David Cage.

For all of their aspirations in the fields of story and world building, the above games are also--intentionally or not--very silly indeed. Metal Gear blends heavy political discourse with poop jokes and scenes of the protagonist uncontrollably wanking. Assassin’s Creed tempers smart, oh-so-earnest alternative histories with ludicrously contrived, disjointed sci-fi conspiracies and apocalypse-touting holograms. Heavy Rain is tonally great, but has more plot holes than a justification for government spying processes, and a seriously juvenile attitude towards character nudity.

Maybe I’m worrying over nothing. Maybe the mass adoption of consoles over the course of this passing generation is going to see the game aesthetic understood and accepted in large enough numbers for a much diminished loss in translation over the next few years. In a generation or so, maybe the general populace will be game-literate enough that the confused dissenters will become a marginalised fringe group. But I’d rather they didn’t have to. The last thing I want is for games to lose their lunatic brilliance, but I also that hope next-gen developments bring more stories that aren’t flat-out bamboozling to the ‘normals’. I think that’s pretty important, and something we’ll all benefit from.