Super Mario 64 turns 25: Examining the impact of the N64's most revolutionary game

Industry icons join Retro Gamer to look back at the N64 launch title that changed 3D gaming forever: "Mario 64 showed the way forward for the whole industry!"

Nintendo has always been a company that has set its own agenda, and that has rarely been more apparent than it was with the N64. Rather than following the likes of 3DO, Sega, and Sony into the CD-ROM market, it stuck doggedly to cartridges. Instead of simply evolving the SNES pad, it produced a radical three-pronged controller design. Neither of those design choices proved to be the future – it’s a tall order to convince an entire industry to do things differently, after all. The thing that made people take note was Super Mario 64, though – a bold and unique design, just like the machine it ran on. However, unlike its host hardware, it made a profound impact on the rest of the industry, shaping the development of future platform games and 3D games in general for years to come.

Of course, Super Mario 64 had to be a bold design. The one common feature of 3D platform games released before Super Mario 64 is that they were all distinct creations, as no two developers had the same vision of how to adapt the genre to the polygonal revolution. Exact gave us Jumping Flash!, a game which offered free-roaming stages, viewed from a first-person perspective. Realtime Associates delivered Bug!, which featured 3D stages comprised of interlocking straight paths, thus strictly regulating player movement. Xing’s Floating Runner utilised free-roaming stages but employed a fixed perspective that made it feel almost like a top-down 2D game. Even if Nintendo had wanted to follow convention with Mario’s 3D debut, there was simply no convention to follow.

The other reason that it had to be a groundbreaking game was the weight of expectation placed upon it at the time. “Up until Mario 64, and probably until Mario Galaxy, there has always been expectation surrounding a new Nintendo console and with it a new Mario,” says Paul Davies, who was the editor of Computer & Video Games during the development and release of Super Mario 64. “So, even though we had no idea how this would shape up, the prospect of Ultra 64 Mario was enough to affect your breathing for a while.”

Ahead of the competition

"Yes, we did go to the zoo and observe the gorillas": The making of Donkey Kong Country

Even those close to Nintendo weren’t aware of what was in the works. “I was working for Software Creations at the time and they were part of the original ‘Dream Team’ of developers working on N64,” recalls John Pickford. “I was lucky enough to be part of a group to visit the Shoshinkai 1995 show in Tokyo for the first unveiling of the Ultra 64 and its software. When we landed at the airport I remember bumping into several other British developers, including the Stampers from Rare and David Jones from DMA design. David said something along the lines of, ‘I hear Mario is looking very good.’ That was the first time I had heard there was a Mario game in development. There had been zero publicity or even mention of Mario until that point.”

Placards at Shoshinkai said that the game was 50 percent complete, and even described Super Mario 64 as a temporary title, but that wasn’t the impression that attendees took away from the event. On a visual level alone, Nintendo had already produced something stunning. “The game was shown on the show floor – looking finished and playable,” says John. “And like nothing else I’d ever seen.” Paul was also attending the show, and the game made a similar impression on him. “It sounds incredibly corny, but I couldn’t believe my eyes. I was gobsmacked, bowled over.”

That initial showing elicited strong emotional reactions from all who saw it. “I was so excited, I tried to impress the hotel staff with my bagful of press materials and transparencies,” Paul confesses. “They were not impressed.” According to John, other people were feeling something closer to fear, or at the least denial. “I don’t know if it’s true but I heard a rumour that ‘Sony execs’ were going around telling people that the game was running on hidden ‘workstations’,” he recalls. “Hard to believe now but a lot of the technical elements (MIP mapping, filtering, perspective-correct textures, z-buffering, hardware anti-aliasing) were all new to consoles and not present on PlayStation.”

The version of Super Mario 64 shown at Shoshinkai in November 1995 might not look immediately recognisable to fans – even the familiar entrance hall of the castle is different, lacking the cloud murals and even the central staircase seen in the final game – but that incredible visual polish carried over to the finished game because there was no fabrication or trickery involved. The N64 was perfectly capable of all of those features, and gave Super Mario 64’s worlds and characters a feeling of solidity that immediately placed both the game and console ahead of the competition.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

“Everything just worked so incredibly slickly,” says Andrew Oliver, then running Glover developer Interactive Studios. “In the ‘other camp’, we’d been amazed by PlayStation’s 3D capabilities. But, whilst Sony pushed all developers to make 3D games, many of us struggled with certain aspects. Cameras were shaky, 3D meshes showed cracks, textures warped and getting a third-person character to feel really nice and for the camera to track it well always seemed just out of reach.” Nintendo’s game exhibited none of those problems. “Mario 64 was so professional, no shake, no shudder, or warping or cracking textures. The PlayStation was 32-bit with integer maths and the N64 was 64-bit with floating-point maths, so there was good reason it worked so much better.”

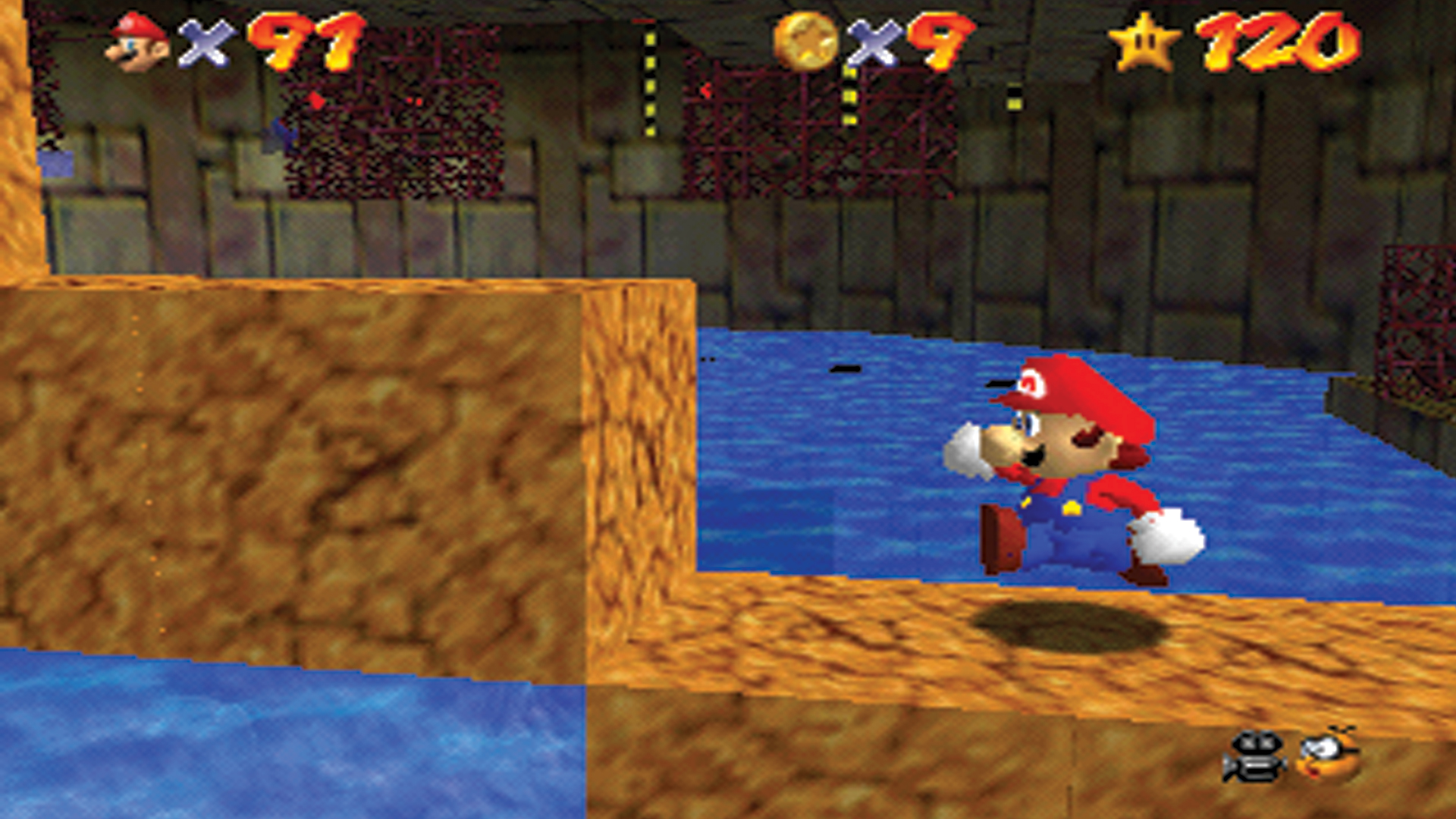

Mark R Jones, a former artist for Ocean, was similarly taken aback by the leap in 3D quality. “The graphics were jaw-dropping. I’d only really played a few 3D games on the PlayStation and this was a massive improvement,” he remembers. “Round things looked round and not like a series of joined-up straight lines. The colours were bright and vibrant and, despite many games claiming that playing them was ‘like controlling a cartoon’, I think that with this game it had really and finally happened for real. I remember everyone at school saying that Knight Lore on the Spectrum was like a cartoon back in 1984. But really it wasn’t. Mario was the real thing. It had actually happened.”

A turning point

If you want in-depth features on classic video games delivered straight to your door or digital device, subscribe to Retro Gamer today.

The press immediately set the hype train in motion. New images would appear in magazines every month, whipping anticipation up to fever pitch – but it wasn’t just the public that was excited. Even developers couldn’t wait to get their hands on the game. “Being a fan of the 2D Mario series I was fascinated by how they’d brought Mario into 3D, what problems they’d encountered and the approaches they took to tackling them,” says Chris Sutherland of Playtonic Games.

At Rare, then a Nintendo subsidiary, he served as the lead programmer on Banjo-Kazooie. “One might have expected the transition to 3D to have been gradual, e.g. Nintendo could have taken a traditional 2D Mario course and given it hints of 3D (similar to the Donkey Kong Country Returns) but instead they jumped in head first to give the player an immersive world to explore,” he continues. “This set the benchmark – anyone releasing a 3D platformer thereafter on N64 was going to be compared with Mario by players!”

"Word got around the Killer Instinct barn that the new Mario game was in the building so we all piled into Chris Tilston’s room for a gander,” recalls Chris Seavor, another former Rare developer who led the development of Conker’s Bad Fur Day. “I think this was a little bit before it actually released and it was the Japanese version, so nobody could understand any of the text. Needless to say it was pretty mindblowing. I’d never seen anything like it before. Then Tim [Stamper] turned up looking rather mortified that we were all seeing this ‘super secret’ thing and took it away… Still, I’ll never forget that moment.”

Andrew’s first experience with the game was equally memorable. “It was the summer of 1996 at the relatively-new E3 show in Los Angeles – Nintendo had a huge stand with around 30 N64s set up and dedicated to Mario 64 and people queuing three deep to take turns. Most were running around outside the castle – just enjoying the experience of running Mario around a beautiful cartoon fantasy world. They nailed the feel-good controls of a character running around a 3D world. Everyone was beaming – it was a turning point for the industry.”

Playing the plumber

The importance of solid controls to Super Mario 64 can’t be overstated. “It was the first time I had played a game where messing around with the character’s abilities was a lot of fun even with nothing specific to do,” says Gregg Mayles, a Rare developer and Banjo-Kazooie’s designer. “It has still not been beaten, in my honest opinion,” Chris Seavor adds. “Slick, tight, great animation and totally intuitive. The first attempt at such a control type and they nailed it for the ages.”

In fact, he found that even the difficult aspects of controlling the portly plumber provided satisfaction. “There was a particular mechanic that took me ages to get to grips with, which involved jumping off a wall, I just couldn’t do it. Then one day all my muscles suddenly twigged, and the sheer joy of jumping up and up from wall to wall, in 3D, was a revelation.”

Paul’s first impression of the game centred on “using the central, solitary analogue stick to help Mario perform backflips and dodge and weave around the first level of the game”, and it was the analogue stick that did a lot of the work in making the game feel so good. John explains the appeal well: “The self-centring thumbstick was the first viable analogue joystick I’d come across. Analogue sticks have been around forever but they were always near-enough impossible to use. Mario had effortless, expressive, intuitive control of a character in a 3D world,” he says.

“Back then, it was more or less accepted that 3D platformers don’t work. There had been a few noble attempts but they were all difficult and confusing to play. Usually the gameplay was about overcoming the controls and camera restriction,” he continues. “Mario 64 had you running, skipping, backflipping, climbing trees and even flying. Nintendo had done the impossible.”

Freedom to explore

“With Super Mario 64 being the first of its kind, that became the de facto place to look for inspiration to solutions when we started building 3D platformers on N64.”

Chris Sutherland

Of course, all of that excellent control would have been for nought if the game didn’t provide adequate space to utilise it, and challenges to overcome. Nintendo delivered in both regards. Paul remembers the sense of disbelief in the office at the time. “The art designer of C&VG was asking me all these questions, because he doubted that much of what he had heard was true: ‘Can I just run onto that bridge and jump into the water? And then I can swim? Under the water?’”

For Gregg, the structure was as important as the space. “3D games up to this point felt restricted in where you could go and what you could do, but Mario 64 removed these restrictions,” he explains. “The freedom made the worlds a joy to explore, coupled with a progression system which allowed you to tackle challenges in the order you wanted to.”

Instead of the simple ‘reach-the-goal’ gameplay of 2D platform games, each course in Super Mario 64 offered a selection of challenges, each of which awarded a Star upon completion. They could range from simply locating red coins to defeating bosses, winning races or just difficult platform challenges. Even Peach’s Castle, the hub through which every other level was accessed, held Stars to find. Naturally, every player had their favourite moments. “Cool Cool Mountain was a favourite,” says Gregg. “The way the slide race connected the top of the level to the bottom was really clever and Mario getting stuck headfirst in snow after a long fall was pure, indulgent charm.”

“My memory is really fuzzy, but when I try to recall anything it’s like looking at my happier moments of childhood,” says Paul as he recounts some personal highlights. “Swinging Bowser by the tail. Finding that bottle underwater somewhere and being convinced that it held a door to a secret zone or something. We thought there would be treats hidden everywhere, and usually there was. Chasing the rabbit, because it was running away so may as well, and being led to something special.” Mark found himself astounded by the longevity of the game. “Even later on, after you’d been playing the game for hours, there were new things to see,” he remembers, “like when Mario turned into liquid metal. You then have this completely metal Mario, like the baddy from Terminator 2.”

"Even more than ten years later it was quite common to see programmers boot up Mario 64 to see how some aspect of the controls or camera systems worked,” says John. “I’d say the first result of that was Tomb Raider which clearly benefited from that Shoshinkai 95 showing – particularly with the swimming controls.” Mark has a similar take on the game’s influence.

“It did definitely pave the way for the next generation of 3D platformers. Later games like Banjo Kazooie and Donkey Kong 64, two of my most favourite N64 titles, wouldn’t have been as good had Mario not been as well put together,” he remarks. “You can just see the programmers at Rare having Super Mario set up next to their stations looking at it and saying, ‘Right, now we have to do that bit better.’ And in a lot of cases, they did. But Mario showed the way forward.”

Mark is dead on the money – the developers at Rare were definitely influenced by the work of what was then their parent company when creating those games. “At the time we [were] experimenting with a ‘2.5D’ look for a platform game that felt like an evolution of the Donkey Kong Country games we had created, but after seeing Mario 64 we knew fully-3D worlds were going to be the future,” Gregg confirms.

“In the past if we’ve looked to solve a problem we’d often look to see how other games have tackled similar issues,” Chris Sutherland says. “With Super Mario 64 being the first of its kind, that became the de facto place to look for inspiration to solutions when we started building 3D platformers on N64.”

Making improvements

Super Mario 64 helped define Nintendo's 1996 console, but what were its greatest releases? Here's our definitive guide to the best N64 games to help you answer that question.

However, there were definitely areas in which the Banjo-Kazooie team looked to improve upon the Super Mario 64 experience, and they put a lot of effort into distinguishing their game from Nintendo’s classic. “We wanted to ensure Banjo-Kazooie had the Rare feel. I wanted Banjo the bear to have a very solid and predictable feel to his control, as opposed to the higher level of skill required to master the inertia that sometimes made Mario’s control challenging,” notes Gregg. “I also wanted our worlds to feel a lot more grounded, basing each one in believable realism that was given a fantastical and humorous twist.”

“We wanted to see more visual detail,” Chris Sutherland elaborates, “especially as we’d just been producing very detailed pre-rendered visuals with games like Donkey Kong Country. The challenge is to not overwhelm the player with detail – it still needs to be clear what items can be walked on, when a floor is slippy and so on. Likewise, we wanted the architecture/geometry of the worlds to be more complex and interesting – but in doing so, the camera that follows the player needs to become more complex and clever to handle unusual situations and to avoid confusing the player.”

Getting the camera right is a task that Gregg remembers vividly. “When I played Mario 64 I didn’t feel the camera was that good, but the reality of just how hard a job this is to get right become apparent when we created our own camera systems,” he reminisces. “In hindsight, Mario’s camera had the right goals in trying to be as dynamic as possible and mostly got it right. The 3D worlds that we created were even more complex than Mario’s and created major headaches for us. Sadly a good camera system is invisible and something nobody talks about, but one that has even minor problems gets a lot of attention.”

With Rare more accustomed to 3D game development by the time of Conker’s Bad Fur Day, many of those initial technical challenges were less of a problem. Still, it was a game which tried to top Super Mario 64 in certain areas, and Chris Seavor pulls no punches in pointing them out. “The visuals… let’s be honest, Mario 64 had some ugly-looking assets in there,” he notes, and it’s fair to say that Conker came out ahead in this regard thanks to Rare’s knowledge of the N64’s hardware, and particularly its texturing quirks. The structure of the game was tweaked too. “We also added more of a narrative to the world, driving the player forward not so much to get the next Star, but to see where the stories and characters lead you.”

Still, Gregg is under no illusions as to how difficult it was to compete with such a groundbreaking game.“Mario 64 got so many things right that it was hard for following games to make significant improvements,” he opines. “Other games had more impressive visuals, used the performance of the hardware better and created worlds that had more depth, but few got close to matching things like Mario’s control.”

3D future

Over at Interactive Studios, the Glover team was discovering the same thing. “Mario set a high bar of quality to meet,” says Andrew. “We were prototyping Glover, first on PC and then on an N64 dev kit, and we were getting great results that we were very happy with. But suddenly, we were playing a huge game that had solved a few problems more elegantly that we had. For example, it had smoothed-skinned characters, unlike the hinged, segmented 3D characters that PlayStation and Glover had! We decided we had to ensure our characters looked just as smooth and had to work out how to make an animated skinned character renderer.”

That wasn’t the only innovation that Andrew and the Glover team had to compete with. “We just spent ages trying to work out what the logic was for the camera so we could get somewhere close,” he remarks. “Technically we figured out most things, as Glover demonstrates, but Mario was still obviously a better game.” With the developers telling us how far they went to match Nintendo’s effort, it’s clear that Super Mario 64 had a huge impact on videogames, so we asked them to quantify it. For John, it was a game that accelerated the pace of progress in game development. “Nintendo solved the problems of third-person control in 3D video games and presented the industry with a ‘how to do it’ in the form of Mario 64,” he says. “I think the industry would have figured it out eventually without Nintendo’s help but Mario 64 saved us probably five years worth of failed experiments and clunky controls.”

For Andrew, it was nothing less than proof that polygon technology was actually viable. “It made everyone realise that 3D was the future, and not just of driving games, but all games! It looked so good, and gave some personality to the characters,” he says. “The worlds were big and interesting and it immersed players in a deep and beautiful fantasy world. Over on the PlayStation, it still felt that 3D was struggling and whilst technically impressive, the gameplay or graphics were generally suffering for the 3D experience. Mario 64 showed the way forward for the whole industry!”

“It was the first of its kind and a genuine ‘Wow Moment’ in gaming that excited even the most jaded of people. It was a combination of revolution combined with one of the most prominent and successful series of games,” says Gregg, summarising the legacy of the game. However, he also adds an important point: “It’s also stood the test of time. Play Mario 64 today and it’s still got the ability to transform you into a playful child where just doing things without thought is great fun.”

A lasting impression

That’s the key thing to remember about Mario 64. It was undoubtedly a groundbreaking and technologically impressive game, as the developers we’ve spoken to have testified. Time marches on though, and other games have entered the conversation as points of reference for 3D game design. If Super Mario 64 had just been a technical achievement, we’d remember it as an important release. But Super Mario 64 was always a supremely enjoyable game first and foremost – and the decades that have passed since it released haven’t dulled that in the slightest.

"There were years when I didn’t play it and when I got back into retro games I worried that it might not have aged well and I was hesitant to have another go at it,” Mark confesses. “But I can happily report that even now, with the novelty of the graphics having worn off, Mario 64 is still one of the best and most fun games to play on any machine ever!” He’s in no doubt as to why that is, too. “Nintendo didn’t just rely on the graphics to wow everyone, they also concentrated on the puzzles and gameplay. So they still spent as much time on the gameplay as they had done on the previous Mario titles but had added in this huge world that seemingly burst out of this little bit of plastic you just stuck in the top of your machine before you turned it on.”

That’s why Super Mario 64 is still as relevant today as it has ever been. The kids who grew up with N64s are adults now, and their love for the game and its successors is the reason behind the success of crowdfunding campaigns for traditional 3D platformer revivals, including A Hat In Time and Playtonic’s Yooka-Laylee. Super Mario 64’s supreme gameplay is the reason that people are still playing today, years after most people nabbed that last Star and had a chat with Yoshi on top of the castle.

People simply aren’t tired of the game – and if you needed any proof of that, hop online and look at the abundance of Super Mario 64 speed runs, challenge runs and modified versions. But don’t take our word for it. Dig out a copy of Super Mario 64 and start up a new file. Spend a minute or two pottering around the castle to get a feel for how Mario controls before leaping into Bob-Omb Battlefield. We’d be surprised if those few minutes don’t turn into hours – and years later, developers are still trying to make games that are so compelling.

This feature first appeared in Retro Gamer magazine. For more fantastic in-depth features, be sure to subscribe to the print or digital edition at MyFavouriteMagazines.

Retro Gamer is the world's biggest - and longest-running - magazine dedicated to classic games, from ZX Spectrum, to NES and PlayStation. Relaunched in 2005, Retro Gamer has become respected within the industry as the authoritative word on classic gaming, thanks to its passionate and knowledgeable writers, with in-depth interviews of numerous acclaimed veterans, including Shigeru Miyamoto, Yu Suzuki, Peter Molyneux and Trip Hawkins.