Magic: The Gathering creator Richard Garfield talks game design: "Players look back now and see a bunch of broken cards"

Exploring a decades-long career, and what comes next

I don't think it's an exaggeration to say that Richard Garfield is a legend in the tabletop community. Besides rattling off some of the best board games over the past two decades, he created a certain, indie card game called Magic: The Gathering. I doubt you've heard of it.

Now he's back to the grindstone with his latest offering – the trivia sequel Half-Truth: Second Guess, co-developed with Jeopardy powerhouse and presenter Ken Jennings. It's already blown way past its initial goal on Kickstarter (the target was $10K, but it's currently circling $39,000), and that runaway success doesn't seem to have hit the end of the line just yet. I managed to leap aboard the hype train for a moment to pick Garfield's brain on this, Magic: The Gathering, and previous projects from King of Tokyo to Keyforge.

You can see what he had to say on MTG, Half-Truth, and more below – I've listed my questions (edited for brevity) and his answers below.

GamesRadar+: It goes without saying that you've had quite the career. Is the expectation that comes with this kind of reputation overwhelming?

Richard Garfield: I find it overwhelming how many people my games have reached and how strongly they have affected people’s lives. However, I don’t approach games with an intent of matching the impacts I have made in the past. I follow what interests me the most and sometimes at the end there is a game I want to share, and sometimes there isn’t. Sometimes there is a big audience for it, but sometimes it is a small one. I am very happy making great games for a small audience. At my core I follow my truth, which is that games are a fascinating and wonderful hobby, I will be a student of games all my life, and I am happy whenever my work brings people into the hobby or expands it, even in a small way for them.

You probably know Richard Garfield as the designer of MTG, Netrunner, and countless other games, but he's also an accomplished mathematics professor and the great-great grandson of U.S. President James A. Garfield. He's not the only creative mind in the family, either; his great uncle invented the paper clip.

GR+: Speaking of which, let's talk about Half-Truth: Second Guess. What brought about this standalone sequel, and what makes it different from the first game?

RG: We always knew we wanted to do a follow-up game. The original came with enough cards to play about 20 times and we expected players to want more questions. What form would that follow-up be? We wanted Second Guess to be stand-alone, so players could jump in. This also gave us the opportunity to add some different ways to play – a faster way and team play, for example.

GR+: As a follow-up to the original Half-Truth, was there anything you wanted to address or change from your original design?

RG: My main goal was providing more questions and more ways to play – there wasn’t anything in particular that I saw as needing correction. Our skill at making questions in this format had grown, and the questions are much more consistently good in Second Guess. Half Truth questions are all multiple choice, with three correct answers and three incorrect answers. It turns out, you can do a lot with that format!

For example, which of these are types of bells?

- A: Parsifal

- B: Carillon

- C: Agogô

- D: Frollo

- E: Trouillefou

- F: Gringoire

A good question has a look of hooks to work with and this has a bunch – you might know the bells, you also might recognize words that sound ‘bellish,’ you also might recognize that the wrong answers are characters from The Hunchback of Notre Dame – and that would allow you to eliminate one or more of the possibilities.

They don’t all follow this format, but we found many ways to give players additional angles to approach questions. This did occur in Half Truth, but not as consistently as with Second Guess. My wife, Koni, was the first to come up with the negative answer theme and she did it brilliantly – she had poisonous mushrooms with Magic cards. I hate to admit – she got me with it. I did manage to answer it correctly but I only got one, had I seen the pattern I would have easily gotten all three.

(The answer to the bell question is ABC.)

GR+: Can you tell me what it's like to work with Ken Jennings? I imagine he brings a different perspective to game design.

RG: Ken is an excellent writer, with a terrific sense of humor and he knows trivia as well as anyone does. He was a delight to work with. He helped us develop style guidelines, and to cut back on questions that didn’t work for one reason or another. He helped vet the questions and pointed out questions that might age poorly. He was also supportive of our work, and seemed to genuinely appreciate the questions we were contributing.

GR+: Your portfolio has a lot of variety. Would you say there's a common design philosophy that you bring to each one, or a calling-card that you see as very 'Richard Garfield'?

RG: I like to think of myself as a game-omnivore, and I try to follow that with my design. Because of that, I think it becomes hard to categorize my games. One thread which is quite common though, is that I like to play games which can be played both seriously and casually at the same time and that usually means there is a bit more luck injected in some way. I can play with much broader groups of players if the most experienced player is winning, say, 75% of the time rather than 99% of the time.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

GR+: A project you're particularly well-known for is Magic: The Gathering (MTG). Looking back, is there anything you wish you'd done differently, done more of, or added?

RG: The changes would mostly be things like clarity of rules and trimming out some of the more complex cards. Often people expect me to want to change the balance of the game upon release, but I strongly stand by it. The thing is, the perfect balance for a game changes over time with the maturing of the community. Players look back now and see a bunch of broken cards – cards like Black Lotus. When the game came out, we knew there were decks that would win on turn one, but the players at the time, they were trading black lotuses for land! They weren’t good enough to use them to their capability; I could beat almost all players in most events with an all common card deck. So how is the game going to be better for players if I make those cards worse, in anticipation of them getting good enough to appreciate it? The environment would just get a lot more boring. As it was, there was a lot of excitement as players learned to leverage all the power that was there waiting to be tapped.

Mana and cards are meaningless if you aren’t good enough as a player to use the advantage it generates.

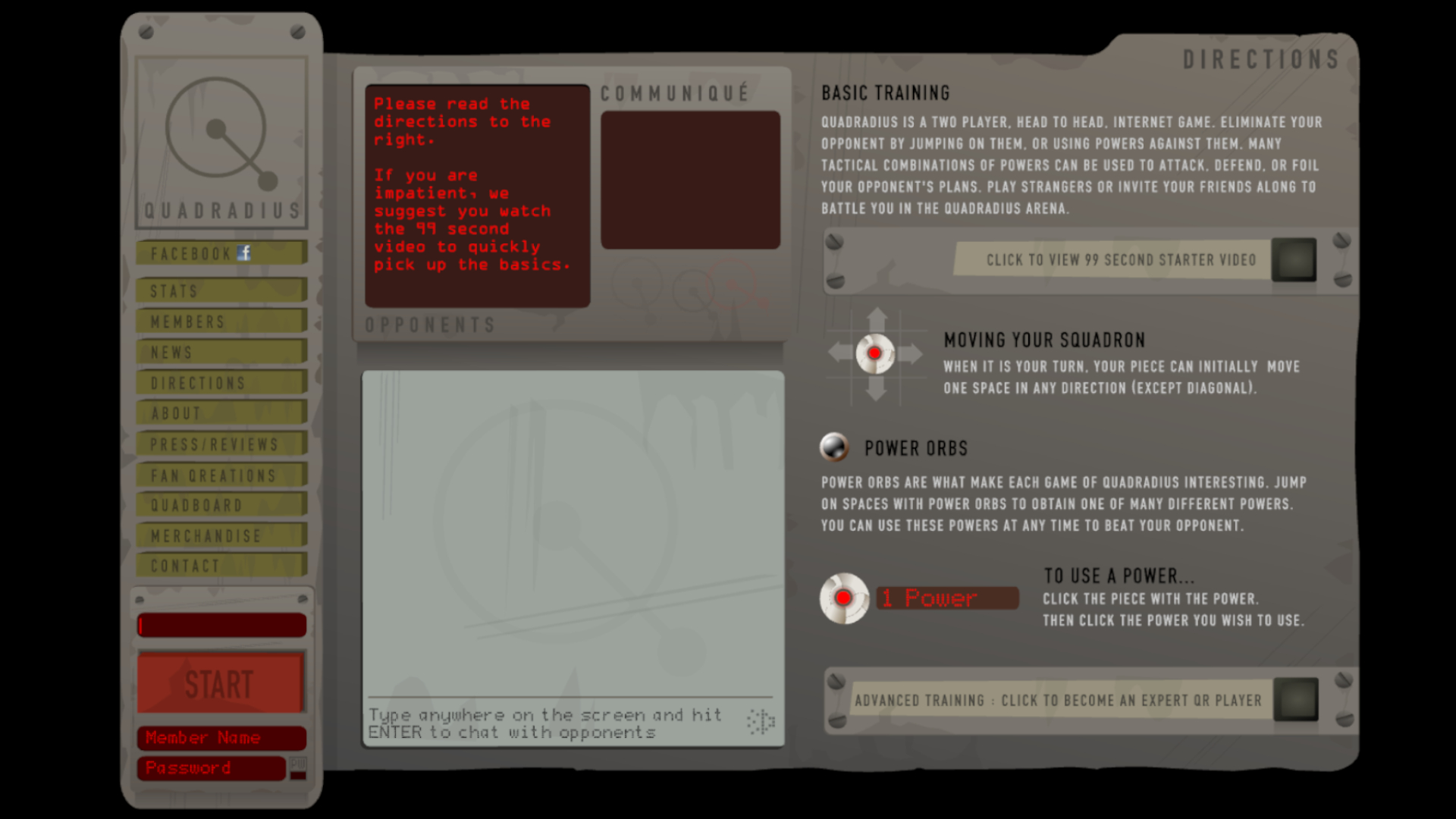

"I am very interested in digital games which feel like tabletop games rather than some sort of simulation. One of my favorite examples of this is Quadradius, which is an amazing game. It may feel like the game is mostly luck, but the more you play it with a good player the more you will realize there is a lot to it. I have played hundreds of hours and will almost always beat new players, but there are players I probably have a 25% win rate against. If you check it out, bring a friend or be prepared to wait a while – the player community is small."

GR+: How does it feel to be responsible for such a beloved and enduring card game?

RG: It is still kind of staggering. It makes me happy to have brought so many people into games and to have contributed to modern design in a meaningful way. There is little I find more rewarding than my work being appreciated.

GR+: On that subject, I'm a big fan of King of Tokyo - it's a great game. Can you talk me through what that was like to make?

RG: People often ask me whether I design theme first or mechanic first and the answer is, both. For The Hunger, it was theme. For King of Tokyo, it was mechanics. I was thinking about Yahtzee, which a mathematician friend of mine was taking very seriously at the time. I thought about how marvelous that game was, and how I might change it. I thought “I would like to add a real theme, and some direct interaction”. I tinkered with the direct interaction for a while— I wanted something where your ability to pick on another player was limited, and soon came up with the King of the Hill mechanic that is used in the final game.

At this point I made a game with a fantasy theme. I did not expect it to be a fantasy game, but I find it a useful placeholder flavor since it is broad and widely understood. After I had a game I liked, Skaff Elias and I brainstormed some final themes and at some point chose a Kaiju theme as being appropriate and exciting.

At this point there is an important step, it is not simply transferring what was there into a Kaiju world. There is some amount of redesign necessary to make the final game feel natural, with the theme more than just painted on.

GR+: Is there a project in your career that you found particularly rewarding, or that you still think about?

RG: I thought for many years about games with unique decks, but it was relatively recently that this became feasible, and my game using this idea was Keyforge. It was exciting in many ways, exploring this design space felt like a process of continuous innovation and discovery.

One interesting thing was that the playtest groups were often negative on the game, because they saw it as lacking deck construction. It made me nervous, but I really believed that this was because the people into massively modular games were big fans of constructing decks, because if you weren’t, you weren’t into those games, since there was no real alternative. It was delightful when the game first came out. There were many people who really loved the idea of not needing to construct a deck but still playing in this game space, and liked the idea that their deck was unique.

The game did quite well for several expansions, but a combination of technical problems and pandemic really killed it. Some games did well in the pandemic, but ones like Keyforge, that are really community based, really suffered.

I am happy that Keyforge has recently been relaunched by Ghost Galaxy, and I like their plans for the game.

This is more than a single game, however, this idea of unique decks is powerful, and there is a lot of possibility still to be explored. One such game was Solforge Fusion. I am also working on several digital games which center on unique player assets.

The trivia-based Half Truth: Second Guess is only on Kickstarter for a limited time, and the campaign ends this November 14. If you pledge, you get an exclusive 18-card promo pack.

GR+: Finally, what makes the medium so appealing in your opinion?

RG: Wow, there are so many things about gaming that make it amazing. I’ll give two answers – one outward facing and one inward facing. The outward facing one is that it allows you to connect with anyone in a relatively safe way. Whether you feel comfortable with socializing with other people or not, a game provides a way to engage. If you know the rules you don’t even necessarily need to speak the same language! This ability to broadly connect people is powerful, and more important than ever.

The inwardly facing answer is that complex systems are often beyond our understanding, but you can explore them in games. Some of these systems may be completely abstract, like Chess, but others might reflect real life systems, like Mafia/Werewolf. We thirst to understand the world and games help.

Inspired? You can see what other tabletop luminaries think in our feature on how one of the most prolific board game designers made it: "The idea of mass market 'being simple' is bullshit." As for what you should play next, why not check out these board games for adults or the best 2-player board games?

I've been writing about games in one form or another since 2012, and now manage GamesRadar+'s tabletop gaming and toy coverage. You'll find my grubby paws on everything from board game reviews to the latest Lego news.