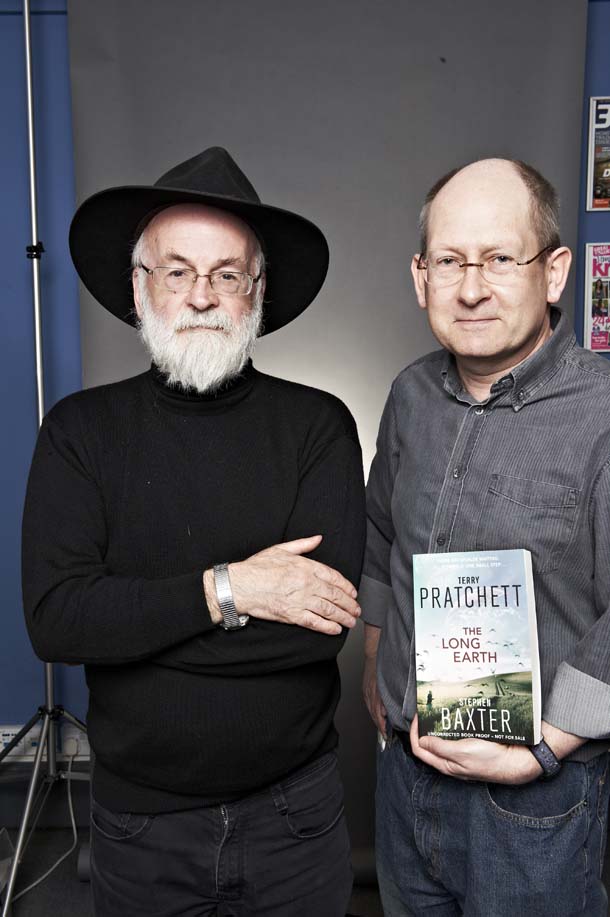

Terry Pratchett And Stephen Baxter Interviewed

Sir Terry Pratchett and Stephen Baxter discuss The Long Earth, the duo’s much-anticipated collaboration. Jonathan Wright hears how the book came about

“You’ve got to make the guys laugh,” protests Pratchett.

In truth, Morecambe and Wise is closer to the mark. While Pratchett is ever prone to flights of fancy, Baxter plays the straight guy to perfection, manfully trying to answer questions about a collaborative SF novel that imagines what might happen if people were suddenly able to step from our version of the planet to endless parallel Earths, but also finding time for deadpan gags of his own.

It’s a terrifically entertaining double act to witness at first hand, a glimpse, you’d guess, of their working dynamic. This, after all, is a duo who can happily bicker over whether unk! or clop! comes closest to describing the noise a large predatory fish makes as it closes its mouth, only to segue to an idea so good that it urgently needs writing down for their next novel together. “Can I have a piece of paper?” says Baxter, and SFX apologetically resorts to ripping a ratty-looking sheet from a notebook.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

Firstly, fortified by the bacon sandwiches and coffee that constitute the Pratchett rider, it’s time to talk about the current novel. It’s a book based on an idea Pratchett initially came up with when he’d just sent The Colour Of Magic to his editor.

Sir Terry Pratchett: “I had the basic idea of quantum Earths, and I thought of trying out one or two short stories and then doing a full-on book. And that might have happened, but The Colour Of Magic was very successful and I thought, after all I was a journalist at heart, ‘If I can make fantasy sell, I’d better get cracking and do some of this stuff.’

“So I put [ The Long Earth ] to one side and I thought, ‘One day I’ll do it.’ It wasn’t until a few years ago now that I pulled it out and thought, ‘You know, there’s some good stuff here, we could take it further and I could certainly do it better now than I would have done then.’ I thought, ‘I certainly need someone else with me, someone that can use the word quantum with a straight face.’”

Sign up to the SFX Newsletter

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

Stephen Baxter: “From my point of view, it kind of emerged more organically. We’d see each other at conventions and I knew Terry was a hard SF reader, having written hard SF himself with Strata and so on. So we’d see each other at dinner parties given by our publishers, and they’d stick us together and Terry would always say, ‘What news of the quantum?’”

TP: “Have you found boatswain Higgs yet?”

SB: “Yes, well I’m looking… At one of these events a couple of years ago we started talking about this project and it came out of Terry’s memory. Maybe he’d recently been looking at the manuscript. The notion of collaborating emerged there. By the end of the evening we were running away with the idea: ‘How about this, how about that?’ To the extent that our hostess got annoyed because it was one in the morning, and a cab had come for me already and left. There she was doing a sort of Alex-Ferguson-with-the-watch thing: ‘Do you want me to call you another cab, Stephen?’ But it came out of that basically.”

From here, the two men kicked around ideas over the phone and at the 2010 Discworld Convention before, eventually, Baxter visited Pratchett at his home.

SB: “I came down to Wiltshire for a weekend, and we sat and thrashed out a rough outline

of who was going to do what.”

TP: “And this man turned up with a spreadsheet.”

SB: “We’ve got different but overlapping styles, I’ll put it that way. I’d say what Terry likes to do is characters, situation and stick them in a room and let them talk and you’re off. And you kind of discover the story that way. With the hard SF I do, what I tend to do is maps and timelines, and try to get some idea of the universe I’m going to explore, which changes as you work your way through, depending on what the story needs.”

More of this interview on the next page…

The eventual score, say the men, has been one hissy fit each and one shared. Plus, adds Baxter, “pub meals consumed, about eight”. More seriously, the men were learning to work together. They reconvened in December 2011.

SB: “I came down for a week. By that time Terry had done a pile of stuff, I’d done a pile of stuff, and I’d stitched it all together roughly and I’d brought down a printout. And we just sat there in Terry’s study, with the fire going and with various Discworld artefacts looking at me, and I just read it through.”

TP: “You could have brought your own artefacts if you’d wanted to.”

SB: “I will next time, I’ll bring a Higgs boson, that’ll scare you. We just read it through. I was making handwritten amendments and notes. There was a fair bit of polishing to do after that but I think after a morning we were both fairly happy.”

TP: “We could both actually see we’d got over the hump.”

SB: “Yeah, we knew we had a book as it were. Being with Terry, life’s never simple. We had to go to Downing Street in the middle, didn’t we? A reception with George Osborne. We were driven up and I was in the back of the car reading until the light failed at four in the afternoon, as it does in December. That was as far as we could get and then we were plastered on cheap Downing Street champagne by the time we came back so we dozed all the way.”

TP: “I was perfectly sober.”

On one of the last occasions SFX met with Pratchett he joked about both men wanting to write the same parts of the book

TP: “This is no bullshit, but I know that there are some bits there that are definitely mine. I know that there are some bits there that fans of mine will recognise. But an awful lot of it, I can’t distinguish between what was mine and what Steve wrote, especially since we were going back over everything all the time.

“It was rather like doing Good Omens with Neil Gaiman. At the end of it two guys had written a book. And you probably know the story: we were going through the proofs and Neil gave a chuckle and said, ‘That was a good piece you wrote.’ And I said, ‘I’m sure it was written by you.’ Occasionally, when we were giving talks, Neil would pointedly put his jacket on the chair and I’d put my hat on top. That was the third person we’d created who was actually doing some of the work.”

SB: “We had the same experience where you’d say, ‘Was that your line?’”

TP: “A couple of times, that’s what I’m getting at. The point is that one reason I was happy to work with Steve is he’s not just got form but pedigree. Anyone who’s good enough for Uncle Arthur [C Clarke, with whom Baxter also collaborated] is good enough for me.”

But whoever wrote which bits of the book, there came a time when those who live inside its pages started to move the novel on.

TP: “The characters will actually start doing things that you weren’t expecting, but which come quite acceptable when they turn up.”

SB: “One example of that is Private Percy, who we open the book with. He was my idea. You brainstorm around the basic idea and I had this notion of a World War One soldier being knocked sideways [to a parallel Earth]…”

TP: “Was that your idea?”

SB: “It was. There you are, you see. You really liked him and you ran with him. You rang up Bernard Pearson [aka the Cunning Artificer, owner of the Discworld Emporium] to research which regiments he might have come from and so forth. And you had the idea of him comforting himself with World War One music hall songs. He was my character, but you ran with him.”

TP: “It was ours.”

SB: “It was ours, yes.”

The idea of people heading out to other Earths calls to mind the idea of the Wild West, the frontier. It’s no coincidence the book’s main characters, a youngster named Joshua and an AI-cum-reincarnated-Tibetan, Lobsang (literally “big brain”) travel across different Earths in an airship called the Mark Twain. The American writer’s Huckleberry Finn famously advised readers to “light out for the Territory ahead of the rest”. Except in The Long Earth , the territory goes on forever.

TP: “That’s actually a big, big thing, because if it happened like that it does absolutely change everything. It changes ideas of wealth, it challenges everything about us as humans. Throughout history, scarcity of things has been what it’s all about so that’s why we fight. There’s only so much stuff and now there isn’t any shortage of stuff. Did we leave in the guy at Sutter’s Mill?”

SB: “Yes.”

TP: “Oh good. This wise guy goes out on the Quantum Earths to where Sutter’s Mill would have been, the California gold rush. And he’s going, ‘This is great,’ and when he climbs out there are people laughing at him and saying more or less, ‘We’ve all got some, there’s lots of it, everywhere.’”

SB: “I think possibly the best SF ideas are really simple. You can describe it in a sentence, like a movie pitch, but you’ve got all these implications from the political, economic, social, personal… what about the guy whose family move to a better Earth but he can’t go because he’s physically incapable of moving, so he’s left behind? So there are endless stories you can generate from endless dimensions. Including the biological, geological, cosmological…”

All of which suggests there’s plenty of scope for more books, especially as the first novel poses more questions than it answers. Besides, among other good ideas, ‘Those Feet Did Not’, a group of Brits who think one Earth is quite enough thank you very much, need to be slotted in and, SFX fervently hopes, so do more sly Gilbert Shelton gags.

Happily, the duo most definitely have plans for more volumes. At one point, SFX asks Terry Pratchett if he has any sense of coming home to SF after so many years of writing fantasy? He looks genuinely pleased by the question, “It was nice, yes, thanks for asking. It was, I suppose, a first love.”

The Long Earth is available now from Doubleday

Ian Berriman has been working for SFX – the world's leading sci-fi, fantasy and horror magazine – since March 2002. He's also a regular writer for Electronic Sound. Other publications he's contributed to include Total Film, When Saturday Comes, Retro Pop, Horrorville, and What DVD. A life-long Doctor Who fan, he's also a supporter of Hull City, and live-tweets along to BBC Four's Top Of The Pops repeats from his @TOTPFacts account.