The 32 best '50s movies

After World War II, Hollywood studios perfected its formulas

In the first decade after the fallout of World War II, the global movie industry hadn’t missed a step. But which of them are actually the greatest?

Throughout the middle of the 20th century, the art of filmmaking evolved through the refinement of the commercial studio style. At the same time, progressive experimentations, like electronic music scoring to widespread adoption of Technicolor and widescreen panorama, took the medium to the next level. While all of that was happening, movie stars grew more accustomed to being the sole reasons why the public went to see movies in the first place.

The arena of cinema expanded throughout the 1950s, too. While American-made Hollywood pictures enjoyed cultural and commercial dominance, movies from other parts of the world – Japan, Sweden, Italy, France, and elsewhere – began entering the conversation.

While the prevailing image of the 1950s may be of wholesome American values, the greatest movies to come out of those years were anything but. Amid Communist witch hunts, the beginning of the Cold War, and the atrocities committed and endured during World War II, the best movies of the 1950s are steeped in paranoia, psychological obsession, and foolish bravery against insurmountable odds. But there was singing and dancing, too.

To prove just how atmospherically diverse the 1950s actually were, here are 32 of the best movies of the decade.

32. The Ten Commandments (1956)

Cecil B. DeMille’s final film is arguably his masterpiece, a Hollywood blockbuster of literally biblical proportions. Based on multiple source texts including Doroth Clarke Wilson’s Prince of Egypt, J. H. Ingraham’s Pillar of Fire, not to mention the Bible, The Ten Commandments follows Moses (Chartlon Heston) from his birth and adoption in Egypt to his acceptance of God’s rules atop Mount Sinai. More than just a lavishly designed epic biopic, The Ten Commandments also tells of Moses’ riveting sibling rivalry with Ramses II (Yul Brynner). Whatever your beliefs, you cannot deny its spectacular majesty. Even now, The Ten Commandments is still what all mega-expensive Hollywood blockbusters should strive to emulate.

31. Cinderella (1950)

After the release of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in 1937, Disney spent the ‘40s amassing power and influence as an animation studio with box office successes like Pinocchio, Dumbo, and Bambi. In 1950, Disney kicked off the decade with Cinderella, a breathtaking musical fantasy about an overworked orphan turned belle of the ball, co-directed by Wilfred Jackson, Hamilton Luske, and Clyde Geronimi. Arguably the forerunner to everything that defines Disney and its specific style of mythmaking, Cinderella stands tall in its universal story of magic, true love, and having the right size feet. Watching it now, and you can’t help but sing, “Bibiddi-Bobbidi-Boo!”

Sign up for the Total Film Newsletter

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

30. Forbidden Planet (1956)

“One cannot behold the face of the gorgon and live!” Before Star Wars forever changed the language of cinematic sci-fi, there was Forbidden Planet. Directed by Fred M. Wilcox and starring Walter Pidgeon, Anne Francis, and Leslie Nielsen, Forbidden Planet is both a glorious pastiche of classic pulp sci-fi and a true innovator, from its groundbreaking fully electronic musical score to introduction of concepts like man-made faster-than-light travel. (Its standout character, Robby the Robot, is also a Hollywood legend in his own right.) Its story tells of a military cruiser sent to investigate the whereabouts of missing colonists, a premise that has been echoed by so many others in the genre in the many decades since.

29. The Seventh Seal (1957)

Since its release in 1957, Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal remains the director’s greatest movie of all time and the one responsible for cementing Sweden’s place in the arena of world cinema. A historical fantasy set during the Black Death, it follows a noble knight (Max von Sydow) who plays the hooded, sinister Death (Bengt Ekerot) in a game of chess. Surrounding them is an ensemble of characters who act in moralistic tableaus that feel like preacher sermons. In a time underscored by horrors like the Holocaust and nuclear bombs, Bergman’s picture altogether defines its era but still feels timeless in its desolation and melancholy.

28. Sunset Boulevard (1950)

Hollywood is madly in love with stories about itself, even the grimy ones. In 1950, the motion picture industry was firmly in a new age where “talkies” were the norm and movie stars began to amass more power and cultural sway. Enter: Sunset Boulevard from Billy Wilder. Gloria Swanson stars as Norma Desmond, a silent film has-been seeking to make a comeback with the help of struggling screenwriter Joe (William Holden). A bleak cautionary tale about the toxicity and fleeting nature of fame, Sunset Boulevard is harrowing as a piece of dark Hollywood self-reflection. It makes a suitable double-bill with pictures like Mulholland Drive, Birdman, Map to the Stars, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, and Babylon.

27. Les Diaboliques (1955)

In this French language psychological horror-thriller from director Henri-Geoorges Clouzot, the wife and mistress of a cruel school headmaster work together to kill him, only to find themselves haunted by their actions when his corpse turns up missing. Les Diaboliques (released as Diabolique in the U.S.) didn’t necessarily invent the horror genre, but its influence speaks for itself; Psycho author Robert Bloch cited this movie as an all-time favorite in a 1983 interview. Les Diaboliques is brimming with tension and paranoia, and must be recognized as a murder mystery that is pulled off flawlessly without even a drop of blood spilled.

26. Roman Holiday (1953)

Audrey Hepburn and Gregory Peck dazzle together in William Wyler’s breezy but bittersweet romantic comedy. In Roman Holiday, Hepburn plays a European princess who wanders Rome and finds herself in the company of a charming American journalist (Peck). Together, the two enjoy an unexpectedly romantic romp through the ancient city, permitting themselves to revel in short-lived ecstasy before resuming their individual lives. In the movie, a tearful Hepburn says, “I don’t know how to say goodbye.” Roman Holiday’s enduring appeal all these years later shows audiences don’t know either.

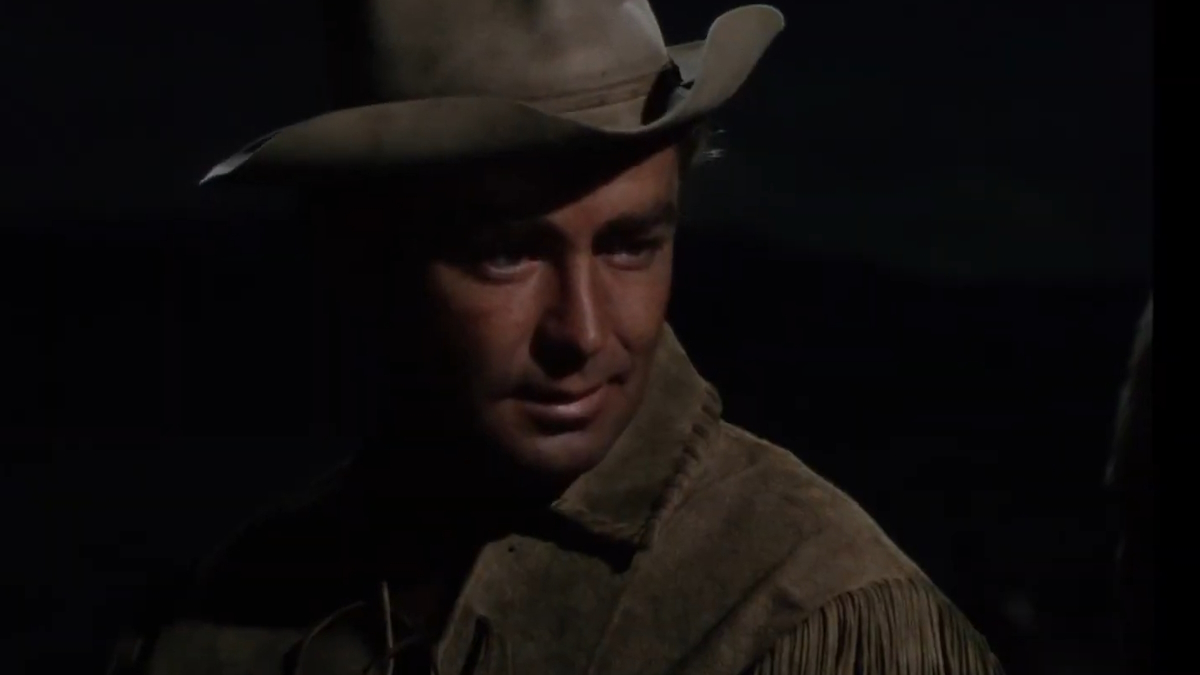

25. Shane (1953)

Before superheroes ruled over cinema, there were the cowboy gunslingers of Westerns. The genre reached its peak in the 1950s, which saw one movie tower above them all: Shane, a gorgeously directed panorama epic from George Stevens. Based on the book by Jack Schaefer, Shane tells of a skilled gunfighter (Alan Ladd) desperately wanting to leave his history of violence behind. After planting roots with a farm family in Wyoming, Shane is forced out of “retirement” to fend off predatory rogues and ruthless barons. In the end, Shane’s ride into the sunset while a child cries out for him to “come back” inadvertently foreshadows the imminent disappearance of Westerns as our ideal representation for heroism.

24. Some Like It Hot (1959)

One of Marilyn Monroe’s greatest movies was also one of her last. In Billy Wilder’s screwball crime comedy Some Like It Hot, Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon star as jazz musicians from the Prohibition era who escape Chicago mobsters by disguising themselves as ladies and join a traveling female band on their way to Miami. The two end up falling for the band’s vocalist and ukulele player, Sugar (Monroe) and begin competing for her affections while maintaining their fake identities. Even if “nobody’s perfect,” Some Like It Hot remains a perfect comedy.

23. Singin’ in the Rain (1952)

Directed and choreographed by Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen, Singin’ in the Rain is far more than its everlasting imagery of open umbrellas, yellow raincoats, and Debbie Reynolds dancing her way to glory. Set in 1927, the end of the silent film era is at hand when movie star Don Lockwood (Kelly), his piano-playing best friend Cosmo (Donald O’Connor), and aspiring actress Kathy Selden (Reynolds) work together on a new project aimed to capitalize on the exciting new technology of synchronized sound to moving pictures. Hilarious and colorful, Singin’ in the Rain relishes the sunnier side to Hollywood’s ever-forward evolution that so often crushes dreams.

22. Gojira (1954)

Over ten years after Japan was on the receiving end of the nuclear bombardment that ended World War II, an unholy monster emerged from the sea to remind mankind of its imminent annihilation. Known to the western world as Godzilla, the original Japanese incarnation Gojira from Ishiro Honda is a towering masterpiece of monster horror where the atrocities of man and beast are indistinguishable. While “Godzilla” has since become a comic hero on both sides of the Pacific, remakes and reboots throughout the 21st century have sought to restore the Big G’s original shades as a Lovecraft-esque nightmare. Some have succeeded. But when they fail, there is still Gojira.

21. The Quiet Man (1952)

Though John Wayne was best known as a hero of Hollywood Westerns, director John Ford gives audiences a different flavor of the icon in his lush rom-com The Quiet Man, based on a Saturday Evening Post short story. Set in the Irish countryside in the 1920s, John Wayne plays Trooper Thorn, an Irish-born American boxer looking to buy his family’s old farm when he falls in love with fiery local Mary Kate (Maureen O’Hara). Filmed in vivid Technicolor, Ford’s picture truly feels alive in its breathtaking snapshots of rural Ireland, not to mention O’Hara’s beautiful red hair that pops against the abundant greenery. While its depiction of gender roles feels wildly outdated, you can’t help but bask in the scenery that Ford captures.

20. Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

Arguably the definitive James Dean movie, the immortal heartthrob shines in Nicholas Ray’s stunning coming-of-age drama that reveals the ugliness bubbling within America’s post-war teenagers. Set in contemporary Los Angeles, Dean stars as Jim Stark, a troubled teenager caught between bickering parents. He begins a shaky romance with another girl from his high school, Judy (Natalie Wood), who is also troubled by problems at home and runs with a tough crowd. James Dean died of a car crash in September 1955, at the age of 24; Rebel Without a Cause was released posthumously just a few weeks after his passing. But the movie’s irrevocable impact has cemented Dean’s status for posterity, ensuring that every generation can see a piece of themselves in James Dean’s sympathetic eyes.

19. Night and the City (1950)

Fearing his own blacklisting amid McCarthyism, filmmaker Jules Dassin escaped to London and made a movie steeped in suspicion, despair, and mistrust. In Night and the City, Richard Widmark plays Harry Fabian, a self-destructive American con-man who gets himself in on the action of London’s professional wrestling circuit. While often overlooked compared to other noir classics, Night and the City hits like a body slam as a seedy thriller that epitomizes British pulp fiction, its back alleys and bar rooms teeming with amoral characters whose only loyalties are to themselves. While two different versions of the movie exist with contrasting endings – one for British audiences, another for Americans – Dassin insists the cynical American cut hews closer to his vision.

18. Tokyo Story (1953)

Akira Kurosawa emerged in the 1950s as one of Japan’s most celebrated auteurs. But among his greatest contemporaries was Yasujiro Ozu, whose modernist, minimalistic style contrasts heavily from Kurosawa’s sweeping operatics. In 1953, Ozu helmed what is widely considered one of his masterpieces: Tokyo Story, about a retired couple traveling to Tokyo to visit their four living adult children. Ozu’s movie, which maintains a slow pace and a camera that almost never moves, explores the Western world’s immediate influence over Japan in the years after World War II and the universal alienation of parents from their growing offspring. While not a comedy, its gentle sense of humor reveals the resplendent beauty found in the everyday lives of the lower middle class.

17. Horror of Dracula (1958)

Years after Universal’s monsters retreated into the shadows, British studio Hammer ushered in its own era starting with Dracula (known in the U.S. as Horror of Dracula) with Sir Christopher Lee as the iconic vampire. In contrast to Bela Lugosi’s iconic yet cartoonish performance as the Transylvanian count, Lee embodies a more handsome iteration that brings to light the eroticism inherent to vampires and their inclination towards neck-biting and blood-draining. (By the way, Lee’s version also introduced dual fanged teeth, which Lugosi did not have in his 1931 movie.) Lee played Dracula in plenty more movies afterward, but his 1958 debut still reigns supreme.

16. From Here to Eternity (1953)

In Fred Zinnemann’s 1953 romantic and somber epic, American soldiers stationed in Hawaii meet their fates in the days leading up to the attacks on Pearl Harbour. While its star-studded cast include Frank Sinatra, Burt Lancaster, Deborah Kerr, and Donna Reed, it’s Montgomery Clift who anchors the movie as Private Robert E. Lee “Prew” Prewitt, a dedicated soldier and talented bugle player who refuses to entertain his captain’s wishes to land him boxing championships. Everyone present, all of them icons from the last stretch of Hollywood’s Golden Age, are in top form as doomed people on the march to when their lives change forever. Montgomery Clift was famously resistant to playing many roles, but From Here to Eternity is easily among his finest.

15. Throne of Blood (1957)

Akira Kurosawa’s enthralling retelling of Shakespeare’s Macbeth stars the indelible Toshiro Mifune, in the role of a samurai analog to Macbeth who learns from an evil forest spirit his imminent future as a castle lord. A cultural fusion of Shakespearean motifs with Japanese Noh theater stagecraft, Throne of Blood is bewitching as a fog-filled nightmare where power comes easy but the strength to hold onto it comes at a great cost. Part political thriller, part horror-fantasy, Throne of Blood is all awe-inspiring that earns immortality in a hailstorm of arrows.

14. 12 Angry Men (1954)

Practically every generation gets its version of 12 Angry Men. But in 1957, director Sidney Lumet brought to the screen an unforgettable production with a cast that included Martin Balsam, John Fielder, Lee J. Cobb, Jack Klugman, Henry Fonda, and more. Based on the 1954 play by Reginald Rose, 12 Angry Men simmers in the disagreements among a jury feverishly deliberating on the conviction or acquittal of a teenager charged with murder. Virtually all courtroom dramas afterward have taken their cues from 12 Angry Men, which contains all its drama to a single jury room but never once feels confining.

13. Ben-Hur (1959)

The Ten Commandments was not the only religious blockbuster of the 1950s. In 1959, Charlton Heston starred in the title role of William Wyler’s award-winning epic of immeasurable scale. Literally hundreds of craftspeople worked behind the scenes, including 100 wardrobe fabricators, 200 artists, 10,000 extras plus some 200 camels and 2,500 horses, all of them needed to push the then-new widescreen format to its limits. But where Ben-Hur inexplicably succeeds is how it still tells the focused story of Judah Ben-Hur, the hero of Lew Wallace’s 1880 novel about a Jewish prince who is enslaved by the Romans and later encounters the one and only Jesus Christ. Even today’s mega-expensive franchise sequels don’t come close to touching the sheer majesty of Ben-Hur.

12. A Streetcar Named Desire (1951)

Based on Tennesee Williams’ Pulitzer-winning play that dramatizes toxic relationships, Elia Kazan’s adaptation stars Vivien Leigh, Kim Hunter, and of course, Marlon Brando. Southern belle Blanche (Vivian Leigh) travels from Mississippi to live with her sister in a crumbling New Orleans apartment. While it helps that the material it’s based on is itself a revered classic in which the best actors can sink their teeth, Kazan’s film version is a true powerhouse in how it captures some of the greatest actors Hollywood has ever seen at their very best.

11. Paths of Glory (1957)

In the conversation about Stanley Kubrick, his 1957 war film Paths to Glory often gets overlooked; his other masterworks like 2001: A Space Odyssey, A Clockwork Orange, The Shining, Full Metal Jacket, and Eyes Wide Shut usually dominate people’s attention. But Kubrick exhibited his unusual but incisive skills as a visual master in his fourth movie. Set in World War I in France, Paths of Glory stars Kirk Douglas as a commanding officer who refuses to push forward on what is essentially a suicidal attack and subsequently challenges charges of cowardice against them in a court-martial. Kubrick was just 29 years of age when he helmed Paths of Glory, and the buzz around his impeccable direction followed him for years after, even after his death in 1999.

10. Hiroshima mon amour (1959)

If an erotic dream could be a movie, it would look like Hiroshima mon amour. In this co-production between France and Japan, director Alain Resnais abruptly drops audiences into the intimacy of a Japanese man (Eiji Okada) and a French woman (Emmanuelle Riva), their bodies covered in both sweat and ash. The movie unfolds in nonlinear fashion, telling about these two strangers’ brief romance in postwar Japan freshly haunted by nuclear devastation. This impossible love story and meditation on international traumas helped catapult the French New Wave to worldwide audiences.

9. War of the Worlds (1953)

Based on H.G. Wells’ 1898 novel, Byron Haskin’s 1953 film version sees contemporary Southern California as the frontier for an invasion by Martian forces. With Orson Welles’ legendary radio broadcast still on audiences’ minds upon its release, War of the Worlds takes advantage of cinema as a visual medium with the remarkable contrast between the primitive artillery of the U.S. Army and the sleek, otherworldly technology of Mars. Innovative as a special effects feast, but immortal as a harrowing tale warning humans can never be too secure as the most intelligent species.

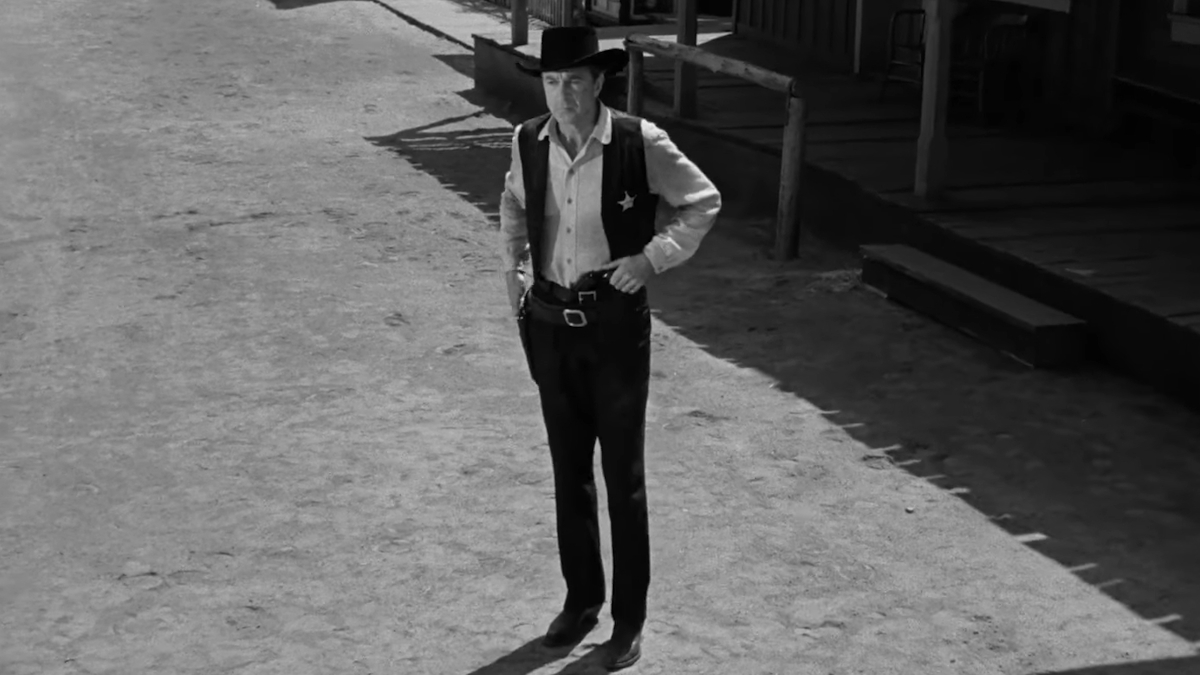

8. High Noon (1952)

Directed by Fred Zinneman, the Western classic High Noon takes place in real time as it follows a town marshal (Gary Cooper) caught between confronting a gang of rogues alone, or escaping with his wife (Grace Kelly). With its potent distillation of Western heroism down to a single man against an evil horde, High Noon helped reimagine and revitalize Westerns for years to come. It should surprise no one that multiple U.S. Presidents have expressed admiration for High Noon, including Dwight Eisenhower, Ronald Reagan, and Bill Clinton.

7. On the Waterfront (1954)

Inspired by a series of Pulitzer-winning articles by Malcolm Johnson for the New York Sun, On the Waterfront reunites director Eliza Kazan with Marlon Brando in a searing drama about crime and corruption on the waterfronts of Hoboken, New Jersey. Brando plays Terry Malloy, a former boxer who intentionally threw a fight at the request of a mob boss. Now working as a longshoreman, Terry is horrified when he’s forced into silence after witnessing the murder of a fellow dock worker. On the Waterfront is one of many movies in the early ‘50s that used its storytelling to condemn McCarthyism, but its story resonates beyond those times as a portrait of helplessness in the face of overwhelming odds.

6. Seven Samurai (1954)

Akira Kurosawa’s epic classic about samurai who unite to defend a vulnerable village, for free, inspires and excites even after all these years. With an ensemble cast led by Takashi Shimura, Yoshio Inaba, Daisuke Kato, Seiji Miyaguchi, and Toshiro Mifune, Kurosawa’s tale spawned its own subgenre of rowdy men who band together for a noble cause than selfish pursuits. Not only has there been direct remakes, like 1960’s The Magnificent Seven (which reimagined the movie as a cowboy Western), but also spiritual homages in movies like The Dirty Dozen, Saving Private Ryan, The Expendables, The Avengers, Justice League, and all across the Star Wars franchise.

5. North by Northwest (1959)

Alfred Hitchcock closed off the 1950s with his spy thriller North by Northwest, an enduring giant of a picture. Starring Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint, the movie follows an innocent man (Cary Grant) who runs for his life across the United States from mysterious agents who believe him to be smuggling government secrets. By 1959, Hitchcock was already a celebrated artist, but with North by Northwest he firmly cemented his brilliance in a movie that was altogether suspenseful and playful.

4. Rear Window (1954)

In this gripping urban mystery, a photographer healing from a broken leg (James Stewart) suspects his neighbor across the street might have murdered someone. With the help of his restless socialite girlfriend (Grace Kelly) and his nurse (Thelma Ritter), Stewart’s character Jeff seeks justice without losing his mind. Even in modern times, when our social feeds make full use of POV filmmaking and our smartphone cameras have made us all amateur photographers, Hitchcock’s movie shows the dramatic power in a limited perspective.

3. Umberto D. (1952)

In this neorealist classic from Italian filmmaker Vittorio De Sica, a poor elderly man in Rome does everything he can to survive with his dog. The movie was unpopular with the Italian public upon its release, given that Italy as a whole was in the midst of postwar recovery and a frail man begging on the streets was not flattering for its image. But audiences everywhere have grown to admire Umberto D. as a heartbreaking story where kindness has been eroded by modernity. A stone-cold classic of world cinema, Umberto D. has precious little to offer but so much to give.

2. Kiss Me Deadly (1955)

Lest anyone think the 1950s was buttoned-up, well-mannered, and full of wholesome values, behold the darkness of Kiss Me Deadly. Robert Aldrich’s film adaptation of Mickey Sillane’s novel tells of a detective, Mike Hammer (Ralph Meeker) who picks up a hitchhiking woman (Maxine Cooper), kicking off one awful, unforgettable night. Hailed as a precursor to the French New Wave and understood as a metaphor for the Cold War, Kiss Me Deadly has influenced the most revered giants of cinema including Francois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, and Quentin Tarantino. It’s simply a towering work.

1. Vertigo

Alfred Hitchock’s psychological thriller Vertigo, released in 1958, is regularly placed on numerous best-of lists; in 2012, it famously toppled Citizen Kane off the coveted number one spot in The Sight & Sound Greatest Films of All Time. It’s hailed as such for good reason. James Stewart stars as John “Scottie” Ferguson, a retired detective who gave up his badge after coming down with acrophobia – a fear of heights. But when Scottie is hired by an acquaintance to follow their wife, Madeleine (Kim Novak), Scottie must confront his fears. With its preoccupation on psychological obsession, Vertigo narrowly splits the difference between riotous entertainment and cerebral arthouse style, sometimes blurring the two in ways that only Alfred Hitchcock ever knew how. Even if you don’t think it’s the “greatest film of all time,” it is undoubtedly one of the best of its decade.

Eric Francisco is a freelance entertainment journalist and graduate of Rutgers University. If a movie or TV show has superheroes, spaceships, kung fu, or John Cena, he's your guy to make sense of it. A former senior writer at Inverse, his byline has also appeared at Vulture, The Daily Beast, Observer, and The Mary Sue. You can find him screaming at Devils hockey games or dodging enemy fire in Call of Duty: Warzone.