The domestic drama of the mid-life crisis simulator is an exciting sign that games might (really this time) be growing up

The issue of maturity has long been a bugbear when talking about games. Whether the perceived problem has been a gung-ho action focus, poor representation of gender, flimsy storylines, or the conduct of the industry itself, the idea of games exhibiting as the truly mature medium they’ve long professed to be has often felt like an aspiration rather than a reality.

But as of this year, it seems like the answer – or at least part of it – might not have been in any one, concerted push to improve, but rather in simply waiting for both games and their audience to grow together in sync. Because as of 2016, we’re seeing a lot more games that seem to acknowledge both the age of the medium and what that means in relation to the age of its audience.

In fact, when I think of this, I can’t help drawing an interesting parallel to Star Wars, and its seemingly impossible – but ultimately clean and triumphant – bid to get good again after the ravaging onslaught of the prequel trilogy. For a time, it looked infeasible that the series could recover from the dirty, six-year glaze of Jar jar, sand-grumbles, and otherwise blistering boredom. But then with The Force Awakens, it did, overnight, and with a seeming minimum of effort. The reason? With George Lucas gone, and the likes of JJ Abrams, Gareth Edwards, and Gary Whitta in, Star Wars is no longer being made by a man who had seemingly long-since lost track of what his creation meant – if indeed any creator can ever interpret their work in the same way as its audience – but by the generation that grew up on it, and could thus understand its essence on an entirely different level.

It feels like we have a version of that happening in games now. The first generations of gamers are now hitting their mid-30s and 40s. And that also means that those people are developing games. As such, games are no longer being played and made with the ‘80s mindset of excitable but naïve Wild West exploration, but rather the experience, insight, and understanding that comes with a lifetime of awareness, not just of the medium but of life itself. And when all of that hits together – as it has in 2016 – it makes for an undeniable change in development attitudes. Older gamers (but most significantly, older gamers who have had their entire lives shaped by the medium) making games for the same are delivering a markedly different conversation than their forbears did.

It’s of course easy to assume that this change in values comes from cynically commercial attitudes. And some undoubtedly does. Older gamers are the ones with the most money – if not necessarily always the most free time – and on top of that, no AAA game has yet been as widely critically-lauded as 2013’s distinctly dad-themed The Last of Us. If there’s cash and kudos to be grabbed, someone will be grasping. But looking back, it’s quite clear that this current wave of ‘mid-life crisis simulators’ has been coming for a while, and certainly not always from a place of crass financial aspiration.

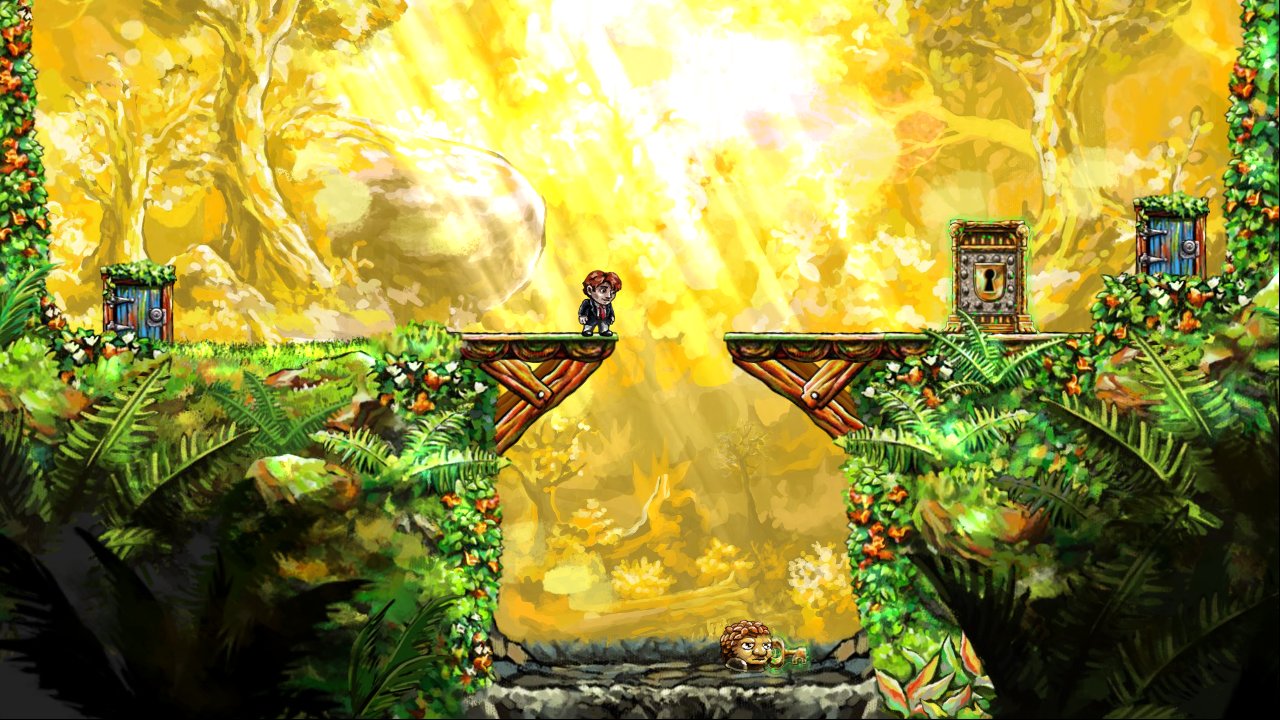

Take 2008’s Braid, for instance. Probably the first Xbox Live Arcade game to truly realise the format’s potential for artistic, expressive games as well as small-scale, retro fare, Braid’s worth as a piece of serious, introspective work (its quality as a platform-puzzle game is undeniable) will depend on where it lands on your pretension scale, but it undeniably exhibits some very interesting traits in regard to 2016’s games. It drips with the visual and narrative tropes of 2D Mario games, albeit presenting a version whose castles, talking dinosaurs, and walking fungus is presented in an altogether more painterly, less cute, quietly grotesque fashion, almost as if deconstructed by mature eyes, like those countless, semi-ironic ‘real-life Kirby’ pieces on Deviantart.

On immediate glance, it feels like the work of an adult looking back on their childhood influences with a more critical view. But then there’s the narrative, which unabashedly uses the ‘find the princess’ trope for far darker, more thoughtful purposes. And the fact that the puzzle mechanics, which largely revolve around rewinding time to change the way in-level events play out, act as a metaphor for many of the game’s narrative conceits. And with the game’s aesthetic acting as a kind of over-arching metaphor for aging self-reflection itself, there’s a whole lot to recommend Braid as the precursor to this year.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Fast-forward to 2012, and Naughty Dog’s The Last of Us, arguably the first, big-budget, morose burnt-out dad-simulator on the market. And coming from the studio behind the resolutely chipper, quip-laden Uncharted, rather a jolt. But an unapologetic one, and greatly successful with it. Taking a risky bet on casting the player not as the cocky, angsty teen, but the broken, disaffected father figure stumbling along behind her, TLoU is, in many way, the antithesis of decades of video game narrative tradition.

In a medium where – no doubt aping the tropes of ‘80s kids’ adventure movies – teens or teen-like adults are traditionally the heroes, and real adults are either absent, bad guys, or background helper characters, The Last of Us delivers the opposite on all counts. And it does so while telling a resolutely bleak, grey-shaded story of parental responsibility, regret, selflessness, selfishness, and the point where personal growth clashes with personal need. It’s a fantastic game, and a sure sign that the studio – whose narrative ambition had been steadily maturing since the days of Crash Bandicoot - had taken an unambiguous step into the truly adult. And in a manner that couldn’t stand further from the gratuitous violence and bawdy sex with which the term is usually associated in games. But what no-one expected, was for The Last Of Us’ ethos to pour through into the next Uncharted game this year.

But pour it did, Naughty Dog choosing to end the series not on the predicted big, glorious bang, but on a distinctly introspective story about a one-time hero trying – and often failing – to referee the grudge match between domestic responsibilities and his innate need for one more adventure. Uncharted 4 stumbles in its execution at times – namely in the use of Sam, Drake’s hitherto nonexistent brothe,r as a supposed emotional catalyst for the struggle, when in truth no more narrative touch-paper than the struggle itself was needed – but overall it delivers a thoughtful and affecting look at not just a hero, but also the nature of heroism.

Where games – and the Uncharted series itself in no small part – typically evangelise heroism as a victory in itself, ditching any complexity in the name of celebrating a big (and often violent) win for the good guys, Uncharted 4 presents the bigger picture. It presents the fallout. It presents a discussion of what happens when being the hero isn’t the be-all and end-all, but just one part of a wider, more holistic human life containing multiple desires and demands. Not the kind of thing an adventuring kid on either side of the screen would ever consider, but a conceit all-too relatable for the older Nate and the older player alike.

Following on thematically from Uncharted 4, we also find Campo Santo’s Firewatch. A less action-packed journey through the wilderness, it nonetheless features another slightly older, equally conflicted protagonist wondering about the reality of his earlier ideals in the face of the wider context of his life. And his story plays on the deconstruction of another, traditionally broad-strokes video game aspirational trope. The romantic happy ending.

Firewatch tells the story of Henry, who has taken a job as a fire look-out at a national park. The reason he’s there? His wife has been diagnosed with early-onset dementia, and moved back home to Australia. And Henry is not sure what to do. Because this isn’t the simplistic, romantic ideal of video games and movies, where you get the girl and then everything is great forever. This is the real world, where the happy ending is actually just the start, and if things go wrong, there’s still a whole lot of life left afterward.

Should Henry go with his wife? Should he stay in the US and start again? Henry recognises that he’s an individual human being with a life, desires, and potential of his own, so should he really dedicate the rest of his days to caring for someone who’s only going to deteriorate, knowing full-well what the inevitable, slow-burn result is going to be regardless of his actions? When younger and more naïve, the grand romantic answer would have been ‘Yes’, but now? Older and wiser, with more questions to answer about who he really is and what he really wants, Henry isn’t so sure.

And Metal Gear Solid 5? Okay, I’m kind of cheating here, as it’s only a 2016 release in its Definitive Experience form. But dear God, Metal Gear Solid 5. Half stealth-action sequel/prequel/whatever, half Hideo Kojima’s own, middle-aged musing on his series’ legacy, the dedication/obsession/madness of his fan-base, the dichotomy between the need for closure and the importance of simply moving on, and how easy it is to lose control of the truth when the modern world would rather argue than conclude, it’s pretty much the definitive mid-life crisis game of the year. Not only packed with mature themes and musings - the like of which would only bother the older, more observant player who’s grown up with both the entire Metal Gear Solid series and the internet’s first 20 years of ‘evolution’ - it’s also a State of the Nation address by one particular, 53 year-old game developer on his work, his career, and his whole outlook on life, as shaped by both of the previous.

And this stuff isn’t going to stop any time soon. Looking forward to 2017, we have the new God of War on the horizon, possibly the bluntest and most fundamental statement of gaming’s older, wiser intent to date. Neither a new game nor the product of steadily evolving sequel conceits, the upcoming return of Kratos looks like one of the bravest and most uncompromising thematic reboots in memory. Turning one of the most brazenly adolescent, rambunctiously violent series’ in the AAA canon into an altogether more thoughtful pondering on the nature of hedonism, rage, violence, and the need to atone, it feels as much a statement about the games industry itself as it does the bearded blade-swinger’s past transgressions.

Taking Kratos – and the player – out of both of the series’ traditional comfort zones, it relocates from ancient Greece to Norse mythology and casts its antihero not as the vengeful, fallen family-man to whom the lost wife and kids are little more than an excuse to kill, but rather a sober, controlled repentant, taking stock of his previous folly while trying not to brutally avenge his dead offspring, but responsibly raise a new one. A game about nurturing new life, not taking it in revenge of past ones. And, if it all comes together as the currently-revealed game systems imply that it will, one in which father and child will learn from each other along the course of their shared journey.

So it feels like we’ve hit a turning point. While the games industry certainly isn’t turning its back on younger players (because children, of course, are our future) it now unambiguously cares about, and is catering for, older ones too. Yes, the medium via which it expresses this care might still often involve the shooting of dudes in the face, and the stabbing of trolls in the kidney, but the context around those actions is fundamentally changing, I said in my original review of The Last of Us that Naughty Dog’s introspective epic is important because, rather than simply being a violent game, it is also often a game about violence. That was an impressive sign of game dev’s growing awareness of its own historical nature, as well as its awareness of its players’ perceptions, but in hindsight it was really only the start.

It seems that The Last of Us’ conceits were just the springboard for gaming’s next (possibly first) wave of genuine maturity. Because games are now no longer simply catering to older players’ thoughts and concerns with references and nods, they’re finally starting to discuss these things too. And that’s important. Because action fueled by open conversation is the most potent sign of maturity in real life, and really, the hallmark of serious, thoughtful art in any medium.