How The Elder Scrolls 3: Morrowind on Xbox thrust open world RPGs into the console mainstream

Back in 2002, bringing The Elder Scrolls 3: Morrowind to Xbox was a risk, but one that blazed the trail for modern console RPGs

In 2002, it would’ve taken some nerve for a game like Morrowind to show its ash-covered, grubby face on home consoles. All this high-fantasy business was yet to become the norm it is today, and RPGs were still a PC or even tabletop phenomenon. Ask a console gamer back then about RPGs, and they’d probably start singing the praises of the Final Fantasy series. Square Enix's legendary franchise undoubtedly set the pace on consoles, but this was the dawn of a new world of open-world exploration, a template for 'western' RPGs that were once the preserve of PC gamers.

On the other hand, this was a time when The Lord Of The Rings was riding high in the public consciousness, proving that Hobbits and Orcs could survive in the spotlight. So perhaps it was the perfect time for the third entry in the Elder Scrolls series to test console waters.

It was a liberating feeling, stepping out of the Census and Excise office in Seyda Neen for the first time and realising, to the timeless twinkle of Jeremy Soule’s score, that you were off the leash to do as you pleased. There was no mod support on the Xbox version, and performance paled next to PCs, but what did console gamers care for such techy twaddle? It was recompensed by the fact that you didn’t have to hunch over a small CRT monitor to explore its unique world, and could instead kick back on the couch or in bed in front of a probably much larger (but equally CRT) TV. Morrowind was foremost a game of scale and immersion, making a bigger screen all the better for soaking it all in.

The scale wasn’t just vast emptiness either. The land of Vvardenfell was believable – a fully realised chunk of world with towns, marshes, fields populated by farmers supplying food for regional capitals and a whole load of ashen wasteland encircling the formidable Red Mountain at the island’s centre. None of Vvardenfell was separated into zones where you’d leave a verdant forest, twiddle your thumbs over a loading screen, then appear in the middle of a desert.

The land felt geographically tangible to a level not achieved in its successors, as even entering cities was completely seamless (although the initial load, as well as reloading saves, did take aeons). It was a go-anywhere, do-anything experience only matched at that time by Grand Theft Auto (the Bethesda marketing team wisely pounced on the inevitable comparisons, slapping press quotes calling it a ‘fantasy GTA III’ on the game box – a good way to lend some kudos to the unfashionable-at-the-time RPG).

How Morrowind pioneered open world RPG exploration on consoles

The charms of Morrowind are encapsulated neatly in the first 20 or so minutes of play. After picking your class, race and star sign at the Census Office, you step outside into the sleepy village of Seyda Neen. To the north, in the distance, you see signs at a fork in the road. This is more than a mere ornamental world- building touch, as you rely on signs – along with directions scribbled into your scrappy journal and the goodwill of passers-by – to navigate the world; without pointers on your compass or waypoints on your map telling you exactly where to go, Morrowind to this day remains a landmark example of unguided video game exploration.

But before heading out into the wild, you could exploit one of the most wonderful systems in the game. Shops in Morrowind were stocked with many of the goods they were selling, and not in some incorporeal way where they were stuck to the shelves, but in the sense that you could actually reach out and nab them. So if you were prepared to live the fugitive lifestyle in exchange for considerable riches and overpowered equipment, then you could walk straight into Arrille’s Tradehouse and help yourself.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Looking back, of course, the theft system was broken. Using it, there was a good chance that by level 10 you’d have near-endless sums of money, and equipment that was far beyond the remit of someone as lowly in standing as yourself. If you were plucky enough, you could even sidestep the entire game and go straight up Red Mountain to take on end-boss Dagoth Ur. It may seem ridiculous, but it also indicated a bold openness that few games today would dare to attempt. It says a lot about the pace of evolution in RPG freedom that the (brilliant) The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild recently received huge plaudits for offering the same option, 15 years later. The fact that world-record Morrowind speedruns have taken under four minutes, while Oblivion and Skyrim’s take closer to 40 minutes, offers some perspective on how unrestricted it was.

So after robbing the shop blind, you make for the road, guided only by the note in your journal telling you to go to Balmora. Conveniently, one of the two directions on the roadsign is for just that town, so you head through mudcrab-infested marshes, only to hear a comical shriek and see an eccentrically dressed wizard plummet to the ground at your feet, dying on impact. In an odd crossover with Greek mythology, on his person are Scrolls of Icarian Flight, which you of course help yourself to and cast without considering that you’d probably meet the same crunching fate as him (once you’d figured out how to equip items using the cryptic UI, that is).

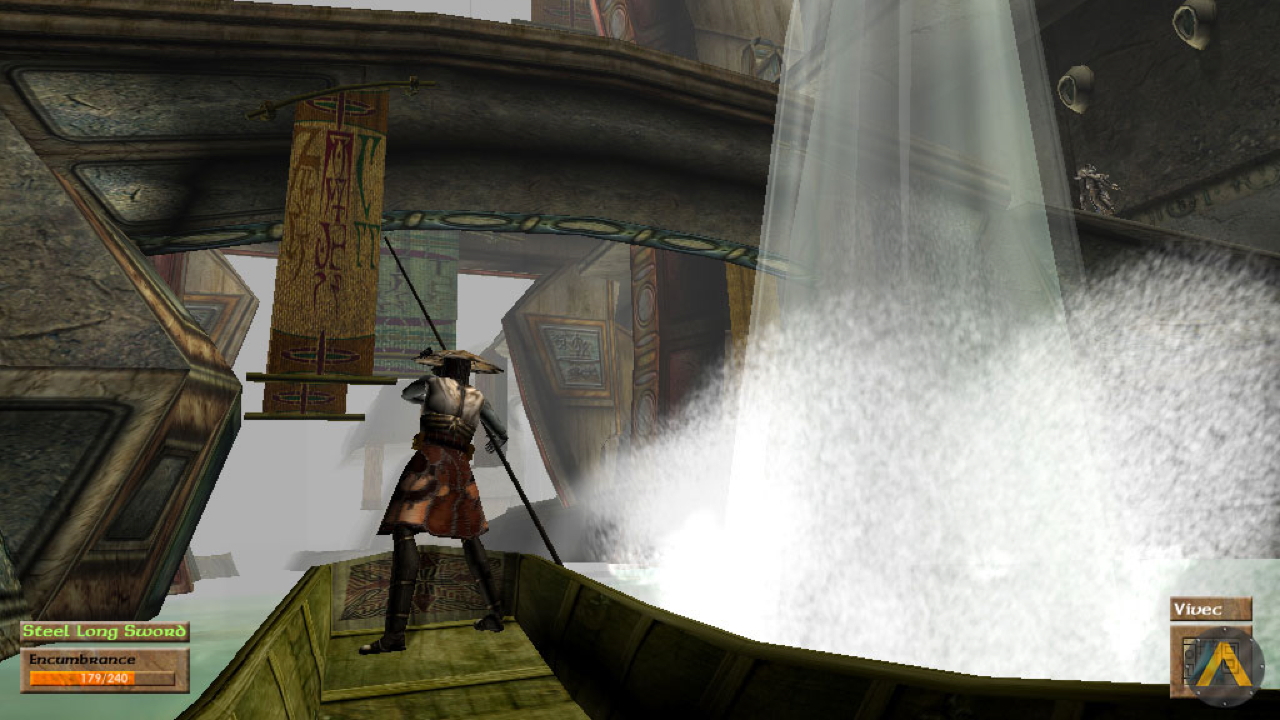

You cast the spell, jump, and shoot through the clouds. If you took a running jump, you could cross about half the continent this way – although, Xbox draw distances being what they were, all you’d see during your flight would be white mist and loading bars until you were about 20 feet from the ground. If you were lucky, you’d land in water and could continue your adventure from whatever far-flung puddle you found yourself swimming in. It was a savvy design choice by Bethesda, exhibiting to players that there really were no limits to this special world even as you reloaded your most recent save.

Before Skyrim's Nordic inspiration, Morrowind explored more fantastical worlds

Despite being a high-fantasy setting of sorts, Morrowind was far removed from the more traditional landscapes of Oblivion and Skyrim. Vvardenfell was a weird place, filled with pterodactyl-like fauna, giant mushrooms, and buildings constructed out of giant crab shells – not to mention the capital city of Vivec, a labyrinthine mess with impressive Mesopotamian architectural inspirations.

The narrative and questing systems were ambitious, coming at a time when the videogame RPG rulebook was still in the process of being written. It starts out as a classic Elder Scrolls ‘chosen one’ narrative – you’re a prisoner who gets a pardon, then embarks on a quest to fulfil your apparent destiny as the Nerevarine – a reincarnation of a god who’s been prophesied to save the land from resurgent tyrant Dagoth Ur.

So far, so Scrolls, but it’s more nuanced than it first seems. Even though you get touted as ‘The Nerevarine’, you’re actually just the latest in a line of five or six, with all the previous ones failing in the same quest you’re now embarking on. Unlike in Skyrim where you’re born with preternatural gifts, in Morrowind you’re just next up on the conveyor belt to fulfil a prophecy.

If you fail in your quest, then perhaps you weren’t the Nerevarine after all, and it’s up to the next pretender to have a pop. If you succeed, then the prophecies are true, and believers’ faith is bolstered; it’s a story about the fallibility and faulty logic around faith, rather than the typical tale of manifest destiny we see in later Scrolls entries. The multiple-choice option right at the finale of the game, where you can state whether or not you believe you are indeed the Nerevarine, cleverly plays on this ambiguity.

Morrowind has an intriguing faction system underpinning many of your actions. Alongside the usual Fighters, Mages and Thieves guilds, there were the five great Dunmer houses – influential, mafia-like families coexisting in uneasy peace and knocking each other off behind the scenes. You could work for three of these houses, but once you committed to one you were tied to it for the rest of the game – a rare instance of an RPG sacrificing certain questlines in favour of others.

To some extent, this was the case across other guilds, as your faction reputation and mastery of their requisite skills would dictate who you could join and how far you could progress in the guild hierarchy. Killing certain people could also permanently lock you off from certain questlines.

At one fascinating fork, the corrupt Fighters’ Guild leader asks you to kill several leaders of the Thieves’ Guild, which would obviously severely dent your chances of joining the latter. Unbeknownst to you, however, this quest is actually optional, and at this point, with enough snooping around, you can continue your Fighters’ Guild progression through another guildmaster, who will eventually task you with taking out his corrupt peer. This would, however, lock you off from carrying out the same task for the Thieves’ Guild later, because your target would already be dead. Broken though they often were, Morrowind had a whole web of underlying systems and intricacies that imbued your actions with a great sense of consequence.

It speaks volumes that the ever-improving Elder Scrolls Online has recently decided to return to Vvardenfell by way of an expansion, nostalgically titled Morrowind. It’s also testament to this 15-year-old game’s world design that the ESO version uses the same heightmap as the original, retaining the same topography that for so many of us – particularly on consoles – marked our first true open-world experience. As world design goes, Morrowind is a rare game of its era that’s proven timeless.

By coming to, and conquering, the Xbox, Morrowind introduced the western RPG to the console scene, revealing that the ostensibly ‘casual’ console audience was more hardcore than publishers gave it credit for. With RPGs today ranking among the most popular games on consoles and PCs, perhaps Geralt and co should tip their helms and pointy hats to Morrowind – one of the most ambitious, majestic and kind-of broken RPGs of all time, which taught us that maybe PC and console audiences weren’t so very different from each other after all.

This article originally appeared in Xbox: The Official Magazine. For more great Xbox coverage, you can subscribe here.

Rob is a freelance games journalist, SEO and content manager. He's written for PC Gamer, GamesRadar, Kotaku, Rock Paper Shotgun, WhatCulture, NextPit, PCGamesN, VG247, Eurogamer, TechRadar, and more.