The making of Enter the Matrix, the game that defied the foundations of interactive storytelling with messy results

The creators of Enter the Matrix reflect on its messy and ambitious development

Games based on a license have been around almost as long as the medium itself, with most gaining a reputation for being cheap tie-ins or ill-produced cash grabs that needed much longer in the development oven. It's an unfortunate fact that, in most instances, the creative teams tasked with making a fun, interactive version of a beloved Hollywood IP weren't given the time necessary to succeed – to the extent that the ET game from 1982 for the Atari 2600 was famously rushed out by a single person and helped cause the US industry crash. After every crash, however, comes a full system reboot.

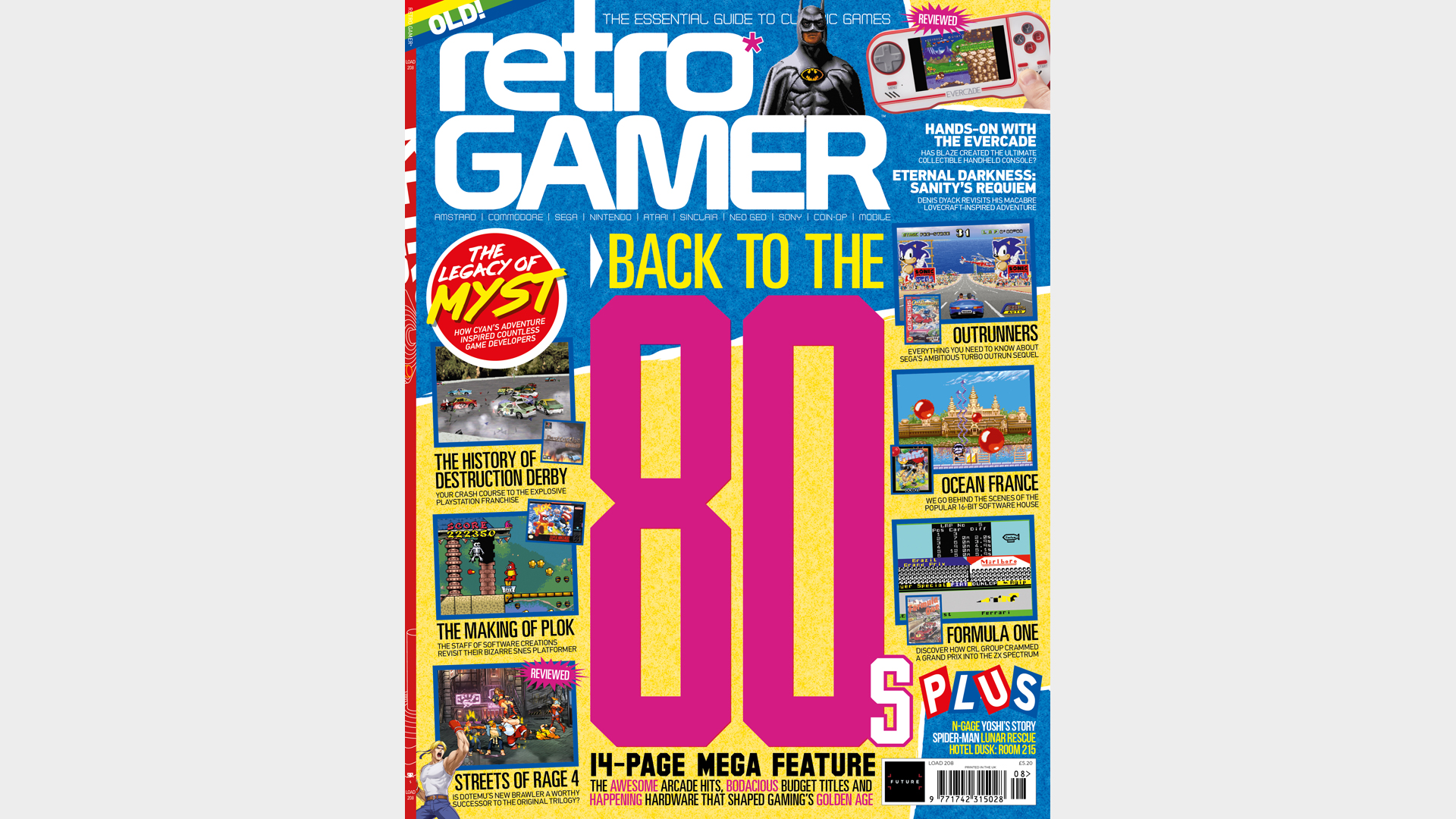

If you want in-depth features on classic video games delivered straight to your doorstop, subscribe to Retro Gamer today.

And it was during the world's reboot at the turn of the millennium, around the time a particular gun-fu sci-fi movie released in cinemas, when Atari was determined to not make the same mistake again. "I was contacted by [film producer] Joel Silver's office," says Shiny Entertainment founder and former game director David Perry. "They had this movie called The Matrix, starring Keanu Reeves. I was a fan of the directors, but we were slammed working on a really cutting-edge 3D game called Sacrifice, so I very embarrassingly passed on the project."

David chalks this up as being high on his "list of terrible career decisions", though it wouldn't be long before he and his team would be given a second chance. They could even use this pioneering tech to translate the Wachowskis' sprawling universe more accurately into a video game.

Most famous for creating the Earthworm Jim series of run-and-gun platformers back in the early Nineties, Shiny Entertainment might seem like an odd choice to develop Enter The Matrix. After all, this was an IP that placed some of life's biggest questions front and centre of a blockbuster movie, asking mainstream audiences to ponder such ideas as 'is the world a simulation?', 'will technology lead to society's downfall?' and 'do humans exercise any free will?'.

All Earthworm Jim ever asked of players was to make it to the end of the level without dying, but it was David's previous history working on tie-in games based on Teenage Mutant Hero Turtles, Disney's Aladdin, and such that helped get his foot back in the door. It was specifically working on The Terminator (1992) on Sega Mega Drive that led to David's surprise about how much involvement his studio would have on the proposed Matrix multimedia project Warner Bros was investing in.

"'Sorry, you can't be the Terminator, and you can't be Sarah Connor, actually you can only use one image of Arnold, and you have to play the guy, Kyle, that dies in the movie'," he reflects, explaining what restrictions around licensed games was like before. "Then along comes the Wachowskis and they want to shoot an hour of Matrix quality movie footage for our game – and write the entire story. It was the most exciting project we'd ever been offered."

Blurring the line

Following rigorous meetings with both the Wachowskis and producer Joel Silver, the outline for what would become Enter The Matrix was agreed upon. It would serve primarily as a third-person action game with driving, shooting and hacking elements, running parallel to the story of The Matrix Reloaded so that familiar characters and events could crossover. Never before or arguably since has a tie-in videogame worked so intimately alongside the production of the property it's based on. The intention was to make a game purposely designed to imbue players with additional narrative context that average moviegoers would be lacking.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

"The Wachowskis explained it to me that they wanted to have two experiences," David explains. "The people that saw the movies would enjoy watching them, but the people that played the games would have a different experience. In the movie Morpheus falls off a fuel truck, but he's saved by Niobe driving a car. As a gamer you had to get that car there, YOU saved Morpheus, but that movie viewer is just happy to see Morpheus survive. So to be clear, if these two people were watching the movie together – after one had played the game – they'd be having very different experiences."

Pulling this off effectively meant Shiny Entertainment had to stay true to The Matrix's established art design and wholly unique iconography. 2003 was a time where dialled-in tablet devices didn't yet exist, maintaining online social profiles wasn't quite an everyday occurrence, and the sight of green code trickling down a black screen was still a novelty. To ensure that Enter The Matrix felt like a legitimate piece of this franchise's puzzle, art director Robert Nesler ate up all the movie assets he could get eyes on.

"[Warner Bros] provided us with a tremendous amount of useful and sensitive material," Robert remembers, "including development clips of the tanker explosion. We were actually given concepts of some, maybe all, of the hovercrafts, the Merovingian's henchmen, some story boards and other stuff. Our senior producer, Stuart Roch, spent some weeks on location in Australia and was able to take a bunch of photographs of the sets. We all of course had DVDs of the first movie that we were able to review for reference."

Like most other aspects of Enter The Matrix's tight two-year development, though, nailing the look of this cyber-obsessed universe wasn't as simple as copying an aesthetic and then calling it a day. No, Robert and the rest of the art department had the challenge of replicating the tonal shift seen in the colour palette of the real world versus the Matrix, having to communicate the visual differences between each in a similarly subtle way to how the movies did.

Robert notes one particular problem that he and the folks at Warner Bros kept coming back to: "Getting the greenish quality in the Matrix to everybody's satisfaction," he reveals. "Owen Paterson, the movie's production designer explained to us that he never felt that the DVDs got it right." This wasn't ideal considering Robert had been using these as a primary reference. "To be honest, I don't recall the exact issue, but I think at the time the method for shifting colour in film was called 'colour timing' and it was a manual/ analogue process. For whatever reason, when the DVDs were made, that quality was not matched exactly and so we were off."

The Matrix's fondness for green was well cemented even before Shiny Entertainment's involvement, but especially so by the time Reloaded and Revolutions entered simultaneous production and doubled down on it. After frequent disagreements and continuous tweaks around the subject, Shiny Entertainment eventually managed to implement a distinctive difference in colour grading between scenes that took place in and outside of the virtual space. However, to this day Robert admits that it was very frustrating and that "I don't think we ever really solved the problem completely".

Enter The Matrix running parallel to the efforts of Neo's main adventure meant that Jada Pinkett-Smith's Niobe and Anthony Wong's Ghost – crew members of the Logos ship – were ideal candidates to be fleshed out as the game's lead protagonists. Whereas the movie would only see the pair crop up for a scene or two, only here could you find out how they impacted events while off-screen. Players were even able to select which revolutionist to play as, so as to witness further variations of the game's exclusive story and encourage repeat playthroughs.

One example is the car chase sequence that takes place immediately after the opening post office level. Opt to play as Niobe and you'll be behind the wheel, evading agents and pursuing police officers as you navigate streets according to the Operator's commands. Play as Ghost, meanwhile, and you're suddenly the trigger man, peering outside the passenger's seat window to take aim and gun down as many threats as possible. Though nowhere near as meaningful as electing to take the blue or the red pill, minor changes like this helped to break up the third-person portions.

Dodging bullets

Speaking of which, Shiny determined early on that its Enter The Matrix game wouldn't feel authentic without adapting the first movie's standout moment into gameplay. The image of Neo leaning back on that cityscape rooftop, dodging bullets in slow motion all as the camera swerves with his trench coat slowly flapping in the wind, had instantly engrained itself in pop culture. Remedy's Max Payne set a precedent for a bullet-time mechanic in games just two years after sci-fi fans witnessed this moment aghast, but Shiny's take worked just as elegantly if not more, keeping the action smooth whenever 'focus' was engaged by having manoeuvres like wall runs and cartwheels be contextual. David Perry thinks it one of the best ways Enter The Matrix captured the franchise's cinematic quality.

"When you experienced it," he says, "it would add so much drama to a moment that would normally be over in just a couple of seconds. Bullet time was used in some other games after the movie came out, I can't imagine the Max Payne game without it. It turned out not to be as big a technical hurdle as expected, but I do love that an idea like that can become part of gaming forever."

Despite being one of the most expensive games ever made at the time, the project was subject to a lot of stress due to the tight two-year deadline. Warner Bros was adamant in having the game release alongside The Matrix Reloaded in May of 2003 and reached a point where funding became an issue. This led to original publisher Interplay losing the rights and an unexpected ally to step in. "Atari bought our company just to get control of the licence," David recalls. "[They] turned out to be a big supporter of the project, so despite all the turmoil it was worth that giant move."

"Then along comes the Wachowskis and they want to shoot an hour of Matrix quality movie footage for our game – and write the entire story."

David Perry

Enter The Matrix eventually released on GameCube, PC, Xbox, and PS2 to middling reviews, with many critics citing its inherent repetition, lack of polish and inability to excel in any one of its core gameplay aspects. Even still, most came to appreciate just how well the game integrated into the wider Matrix canon, with special attention paid to the visuals, actor performances and fun implementation of bullet time. Such a tight development turnaround was the root cause for many of the finished game's issues, but the project still serves as an exemplar that future studios can use for adapting other entertainment media into a video game.

When asked what advice he would pass onto any prospective developers working on a tie-in to the upcoming Matrix 4, David doesn't mince his words. "If they have not already started, I'd recommend they launch a year after the movie. For many reasons they really need Lana [Wachowski] to spend time dedicated to the gameplay after the movie is out. The game could be absolutely incredible given the time, funding and talent that she can bring to the table.

This feature first appeared in Retro Gamer magazine issue 209. For more excellent features, like the one you've just read, don't forget to subscribe to the print or digital edition at MyFavouriteMagazines.

Retro Gamer is the world's biggest - and longest-running - magazine dedicated to classic games, from ZX Spectrum, to NES and PlayStation. Relaunched in 2005, Retro Gamer has become respected within the industry as the authoritative word on classic gaming, thanks to its passionate and knowledgeable writers, with in-depth interviews of numerous acclaimed veterans, including Shigeru Miyamoto, Yu Suzuki, Peter Molyneux and Trip Hawkins.