How Paradise Killer went from "Crazy Taxi meets Gone Home" to a modern indie classic

Kaizen Game Works talks us through the making of Paradise Killer, its surrealist detective game

For both player and developer, the story of Paradise Killer begins with a bold leap into the unknown. The game opens with disgraced investigator Lady Love Dies finding out her eternal exile to the luxurious Idle Lands isn't quite forever after all: after three million days, she's called to investigate the murder of the titular island's ruling council. But there's only one way back, and that's down.

After unlocking the gate separating her from the world beyond, it's time, as she puts it, "to fall into a pit of crime". And so, to the strains of Barry Topping's glorious city-pop score, she steps off. Cue title screen.

It took similar courage for Kaizen Game Works' technical director Phil Crabtree and creative director Oli Clarke Smith to kick off their studio's own adventure. This pair of old schoolfriends had been working separately in the game industry for some time, with several mobile and triple-A games under their belts. The two made bullet-hell endless runner Wonton 51 (under the moniker Quarter Circle Punch) as a hobby project in 2011, and ever since had had the urge to make something bigger and more involved as a duo.

"I liked my jobs, and I'd worked on some really high-end mobile games," Crabtree says, "but they just weren't what I wanted to do." Clarke Smith, project lead on Halo Wars 2 and designer on Supermassive Games' Until Dawn and Man Of Medan, felt the same way. And so they decided it was time to take the plunge and make a new game together.

Good vibes

There was no specific idea in place at the time, but both knew the style of game they wanted to make. The genesis of the Paradise universe began not with Lady Love Dies but with the island's ferrywoman, Lydia Day Break. "We started kicking around some ideas for a narrative game that was like Crazy Taxi meets Gone Home," Clarke Smith tells us. Rather than investigate a multiple homicide case, you'd drive around picking people up at the end of an island cycle, gradually learning about its past through your conversations with passengers. "There wasn't a mystery," Clarke Smith says. "It was just like: go and chill and vibe, and find some weird history."

Though that idea didn't pan out, Paradise was very much at the forefront of the pair's minds for their next concept. This time, it was a top-down shooter with a slower, more deliberate pace and an interlocking, Dark Souls-style world – an idea that brought the character of Akiko to life. "I really like Castlevania: Rondo Of Blood's combat, where each fight feels like a little duel," Clarke Smith says. "So we were trying to do that. At the time, a lot of people were hyped for that Ruiner game – and then it came out and didn't do very much, and it seemed like the world was maybe done with top-down shooters." For the amount of time and budget they'd set themselves, it seemed like too much work, too.

The setting stayed, but everything was pared back to a simpler, walking-simulator-style game: you'd pick up pieces of story about the island and its inhabitants, and end the game when you wanted. "But, as we started making that, we realised we wanted more and more investigation and detective and dialogue mechanics, and it became Paradise Killer."

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

If you want more great long-form games journalism like this every month, delivered straight to your doorstop or your inbox, why not subscribe to Edge here.

How the game evolved from there is a combination of pragmatism and creative ingenuity. The studio knew it wanted an open world to explore, but would struggle to populate it with pedestrians and traffic with the time, money and skillsets at its disposal. Thus came the concept of an island's end: the moment before its rebirth when its citizens are no more. Meanwhile, the concept of the Syndicate – a group of immortals that can move between island sequences – allowed Kaizen Game Works to develop around a dozen key characters. The place itself may be a bit of a sprawl, but the central cast couldn't get too unwieldy.

After that, it was a matter of considering the function of individual pieces, with the narrative built around that. The first part was the conspiracy involving island architect Carmelina Silence and the presence of the Holy Seals, protecting the private room in which the murders take place: these were included to give the player a sense of progression. "That's why we made it a fantasy world – so that we could have complete control over it and just make stuff up as we go along," Clarke Smith says. "But never frivolously. If we put something in the game to serve a function, it has to go back to the truth of the world. It's never 'just because'. If the player can't latch on to anything, then the player can't trust the game, and if the player loses trust then we've got nothing."

Indeed, as Crabtree explains, one of the studio's unspoken rules from day one was that it would trust its players, believing that their choices and actions should be respected throughout. Their agency, too: once Lydia has dropped you off on the island, you're entirely free to explore it – to head towards the various suspects to interrogate them, try to narrow down your search for evidence, or simply wander around at your leisure. "Neither of us are big into that sort of open-world, triple-A handholding, with the shopping list of things that you must do and the overt signposting," Clarke Smith explains.

Freedom to explore

Instead, Kaizen Game Works took the opposite approach: give the player nothing at all, and then determine the minimum assistance needed to make the investigation more enjoyable. "Once upon a time, there was no quest log," Clarke Smith admits. "And then we added that in to help push the player in the right direction – though the text was never 'Go here and speak to this person about this thing'. A lot of it is kind of hints, or if something is more concrete, it's because you've found enough information [elsewhere]."

Then it was a matter of layering on the rest: each character's location was originally held within their bio within Starlight, Lady Love Dies' handy laptop, but Clarke Smith says it was "too wordy". There was no time to develop a proper interactive map, and so the AR mode, which acts as a temporary overlay to show you the distance and direction of each character, proved the best option – not least because it didn't just act as a GPS with arrows guiding you to your destination, allowing players to have their attention drawn by something else on the way. "You see a direction to go in, and then you start heading there, and then you think you're going to go straight to that character. But half an hour later, you're still not there, because you've been distracted by so many other things. And that is what gives the player that will to push on with the exploration, because there's always something to find."

The desire to provide a semi-realistic narrative grounding for the crime itself, however, led to issues with the distribution of evidence: since the Syndicate members are all suspects, it's inevitable you'll find a lot of it clustered around the group's headquarters. "That's why there are so many lore collectibles in the game," Clarke Smith says. "Because if we can get people into the lore, then people will find something around each corner to look at and find." From the detritus that tells us a little more about the world to the whiskey bottles that prompt flash-forward interludes from the 25th iteration of Paradise, they're here to encourage but also reward exploration. "In most open-world games, you're fighting a thousand different bad guys. And so wherever you go, you will get XP or you'll find a new weapon or some new costume or something like that, and because we didn't have any rewards like that, just due to the nature of the game, the collectibles really help with that."

Which brings us to the game's most important currency: blood crystals. Scattered liberally across the island, they pay for a range of things, unlocking fast travel for Lydia and upgrades for Starlight – and can be exchanged for valuable titbits from information broker Crimson Acid. Clarke Smith admits that many players finish the game with a surfeit of them, simply because they included so many in order to encourage players to poke their noses into all of the island's nooks and crannies. At first, everything was more expensive – you'd even have to pay to save the game – so you'd have more reason to spend them.

"But that was not a great experience," he adds. "We dialled down the cost so you would have a less fricative experience but still find some use for them." Crabtree notes that there's still a sense of weight to each crystal in the early game: "Getting those first upgrades or unlocking those first secrets is still hard to come by. So you kind of appreciate their importance. But then, as the game goes on, and you do start collecting a lot more, then it feels a bit more freeing. And I quite like that, because it goes hand in hand with you learning the world more."

Escaping triple-A

As much as you do learn, there's plenty that can be easily overlooked. We recall finding the game's smoking gun on a last-minute detour as we were preparing to head to the courtroom to present our findings. And we know more than one person who never discovered the abilities granted to you by the island's three footbaths – there's a meditation ability that reveals the locations of collectables in the vicinity, alongside a double jump and an air dash that makes some areas significantly easier to navigate. "We wanted to put something in that surprises the player," Clarke Smith explains. "You never get a double jump in these firstperson narrative games. You never get air dashes. It was like, 'What if we could take some kind of action-style mechanics and put them into a narrative game and give the player that level of surprise?'"

Yet they, too, became aware of players so reticent to spend their blood crystals that they refused to, well, foot the bill. "We could have put in something like a phone call from Dead Nebula that said it will be worth your while, but that takes some of the surprise away. The moment of joy when you take the punt, and spend some money, and then get that as an unlock – that's a good experience." Yet if a degree of friction was important to the developer, it didn't want too much: when playtesters complained that the mountain on Paradise was too much of a slog to get around (it was, Clarke Smith notes, originally three times the size), a huge gorge was cut into it.

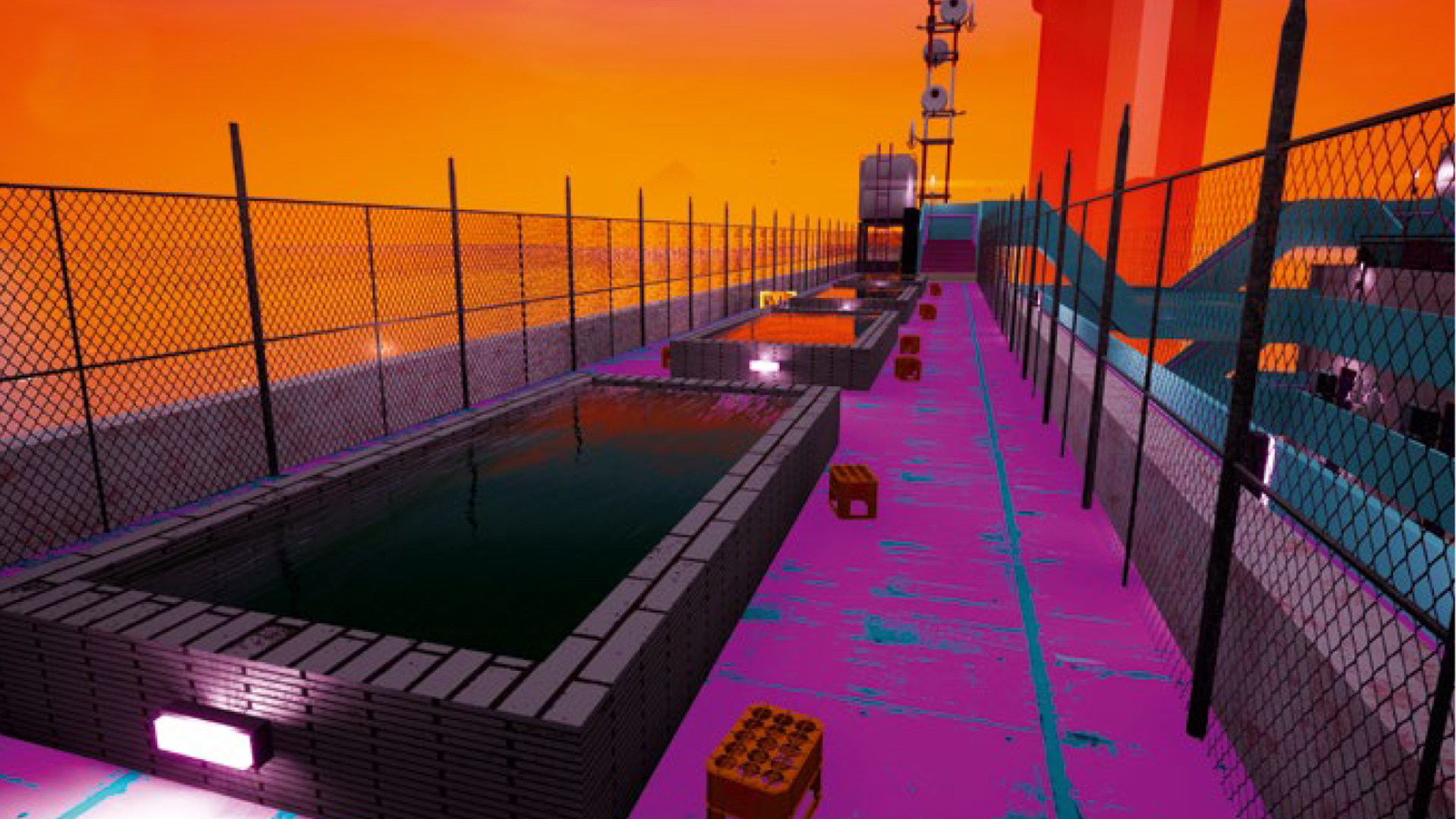

The island changed shape a number of times during development, in fact, particularly once art director Rachel Noy came aboard. With an artist's eye for composition she was able to pinpoint areas of visual density, and highlighted places where landmarks should be, so Clarke Smith could pull areas apart to put in things to draw the player's eye. She also ramped up the game's vaporwave stylings, tweaking colours to make the place pop. "We had a lot of individual pieces – yeah, it looked cool, but we wanted a stronger artistic cohesion," she says. Any crystal and gold objects in the game – and the convenience store – are all down to Noy. "It was a real labour of love. Oli and Phil basically just said, 'Anything you want to do that will make the game better and that you want to have fun with, just do it. As long as it fits, then we'll have it.' And I've never had an experience like that working in games before, really. It was amazing."

That, Clarke Smith says, was the whole point of founding Kaizen Game Works – to escape what he calls "the Eye of Sauron" when you're working in triple-A. "There, you can't just let people do whatever they want. Whereas with this, it was just 'if you believe in something, put it in the game.'" And the response from critics and players alike has vindicated that leap of faith: no one's going to be buying themselves an island paradise of their own, but it's been successful enough that more console ports are due this year, and another game is in development. "Paradise Killer really had to be like a product of our personalities," Crabtree says. "And there's so much of it in there. Like, we know it's a risk, so you may as well have fun with that risk."

This feature first appeared in Edge Magazine. For more excellent features, like the one you've just read, don't forget to subscribe to the print or digital edition at Magazines Direct.

Chris is Edge's deputy editor, having previously spent a decade as a freelance critic. With more than 15 years' experience in print and online journalism, he has contributed features, interviews, reviews and more to the likes of PC Gamer, GamesRadar and The Guardian. He is Total Film’s resident game critic, and has a keen interest in cinema. Three (relatively) recent favourites: Hyper Light Drifter, Tetris Effect, Return Of The Obra Dinn.