The Making Of Taxi Driver

Scorsese goes psycho on the streets of New York

The Beginning

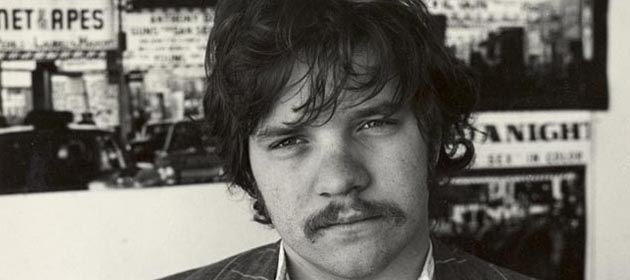

Taxi Driver began with film critic turned scriptwriter, Paul Schrader. In 1973 the 26-year-old Schrader was living a broken life, divorced from his wife, separated from his girlfriend, and living in his car.

“At the time I wrote it I was very enamoured of guns,” Schrader later said. “I was very suicidal, I was drinking heavily, I was obsessed with pornography in the way a lonely person is, and all those elements are upfront in the script.”

Also upfront in the script are several literary influences. Schrader called Jean-Paul Satre’s existential novel Nausea the “model” for Taxi Driver, and he was also influenced by the diary extracts of would-be political assassin Arthur Bremer, whose failed attempt to murder presidential candidate George Wallace earned him headlines in May 1972.

More than anything, though, Taxi Driver was an autobiographical expression of loneliness and anger. “Travis Bickle,” Schrader admits, “was just me.”

What Might Have Been

Taxi Driver was only Schrader’s second script, after a never-produced Robert Bresson-style piece called Pipeliner. The first step towards getting it produced came while Schrader was writing freelance film criticism in Los Angeles.

“I did a review of Brian De Palma’s Sisters, which I liked,” he remembers. “I went to interview De Palma for an article and we struck up a friendship. I let him read Taxi Driver and he liked it a lot and wanted to do it.”

De Palma introduced Schrader to his producer neighbours, Michael and Julia Phillips. They'd just won the Oscar for The Sting, but still, progress was initially slow.

“At that time we couldn’t put the film together because we didn’t have the clout,” says Schrader. “There was a chance to do it with another actor – Jeff Bridges – but we just held out, and a year went by.”

The Director

De Palma wasn’t sure about directing Taxi Driver himself, but the Phillipses had just the guy in mind. Well, actually, they had a few guys in mind, but having flirted with Irvin Kershner, Lamont Johnson and John Milius, they narrowed it down.

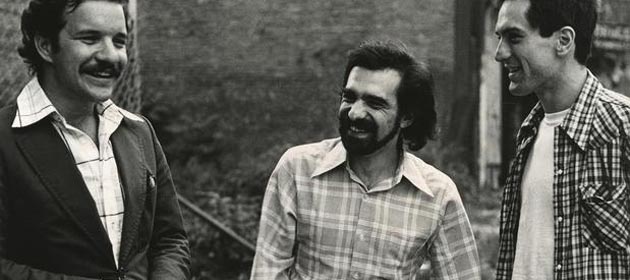

“They felt it would be ideal for De Niro and Scorsese, who was just cutting Mean Streets,” remembers Schrader. “So that was when I first met Marty.”

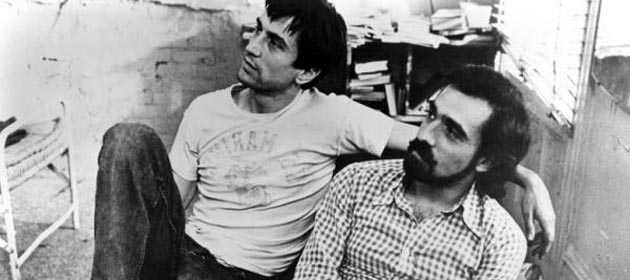

Scorsese read the screenplay and connected with it instantly. “When Brian De Palma gave me a copy of Taxi Driver and introduced us, I almost felt I wrote it myself,” he says. “Not that I could write that way, but I felt everything. I was burning inside my fucking skin – I had to make it.”

Scorsese shared a looming religious upbringing with his screenwriter – Catholic as opposed to Schrader’s stringent Calvinist – and understood the film’s urban isolation perfectly. “I never read any of Paul’s source materials,” he says. “But I had read Dostoevsky’s Notes From Underground years before and wanted to make a film of it, and Taxi Driver was the closest thing I’d come across.”

The Cast

Scorsese had worked with both De Niro and his Taxi Driver co-star Harvey Keitel on Mean Streets, but before the role of Travis Bickle was finally cast it was offered to at least one other famous face.

“I remember meeting Martin Scorsese,” says nearly man Dustin Hoffman. “He had no script and I didn’t even know who he was. I hadn’t seen any of his films and he talked a mile a minute telling me what the movie would be about. I was thinking, ‘What is he talking about?’ I thought the guy was crazy.”

According to producer Julia Phillips, though, Scorsese and De Niro always came as a package. “Marty sidles up to me at parties and tells me how much he wants to do this picture,” she recorded in infamous memoir You’ll Never Eat Lunch In This Town Again. After viewing a rough cut of Mean Streets, she gave in, with one condition. “Get us De Niro to play Travis, and it’s all yours.”

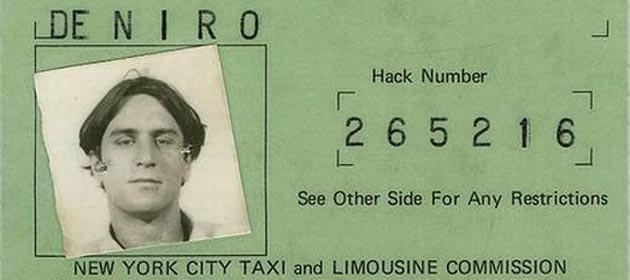

He did just that, and De Niro gave the role the full treatment. He wore Schrader’s jacket and boots to get close to the character, and even flew back from filming in Italy to drive his own cab around New York on weekends.

The Greenlight

Although full of now-famous faces, Taxi Driver caught its collaborators on the cusp of greatness rather than in the full throes of it. It was therefore a pain to get made.

“This picture is one that just doesn’t ever want to start,” Phillips wrote, recalling broken deals with Warner Bros and disinterest from Columbia. Schrader remembers the same. “The script kept banging around, and everyone would say, ‘Gee this is fabulous! But it’s not for us.’”

In the end De Niro left to make 1900 with Bernardo Bertolucci, and Scorsese couldn’t refuse an offer to direct Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore with Ellen Burstyn, flush from success with The Exorcist.

With Alice finished, Scorsese had another studio film to his name, and finally the project had enough momentum to lurch into production. “Michael and Julia figured there would be enough power to get the film made, though in the end we barely raised the very low budget of $1.3 million,” remembers Scorsese. “In fact, for a while we even thought about doing it on black and white videotape.”

Influences

The famously cine-literate Scorsese has always been open on the subject of Taxi Driver’s on-screen influences.

“We looked at Hitchcock’s The Wrong Man for the moves when Henry Fonda goes into the insurance office,” he explains. “That was the kind of paranoia I wanted to employ. And the way Francesco Rosi used black and white in Salvatore Giuliano was the way I wanted Taxi Driver to look in colour. We also studied Jack Hazan’s A Bigger Splash for the head-on framing, such as when Travis shoots the black guy. Each sequence begins with a shot like that, so before any moves you’re presented with an image like a painting.”

Taxi Driver also had a curious connection to the Western. The film has quite deliberate parallels with Scorsese favourite The Searchers (which is discussed by Keitel’s character in the earlier Who’s That Knocking On My Door?), with Travis the John Wayne character reclaiming an innocent girl from savages.

And although it was more stylistically complex, Taxi Driver bore similarities to the recent cycle of ‘Urban Westerns’ – grim, morally blank vigilante thrillers like Death Wish, Magnum Force and Coogan’s bluff, which typically starred American actors who’d made their name as Spaghetti heroes, like Clint Eastwood and Charles Bronson.

The Shoot

The film was shot in the searing summer heat of 1975, with the melting pot of New York raised to a simmering, seething boil and a garbage collection strike leaving the city filthy and full.

Added to that, the production was under pressure and on a tight leash. “Because of the low budget, the whole film was drawn out on storyboards, even down to medium close-ups of people talking, so that everything would connect,” Scorsese remembers.

Phillips, though, remembered the production for different reasons. “Taxi Driver is a cokey movie,” she wrote. “Big pressure, short schedule, and short money. New York in the summer. Night shooting. I have only visited the set once and they were all doing blow. I don’t see it. I just know it.”

The Music

To create the desired atmosphere of dreamlike fury and paranoia, Scorsese turned to veteran composer Bernard Herrmann, most famous for his high-tension scores for Hitchcock’s Psycho and Vertigo.

“It wasn’t easy getting Bernard Herrmann,” says Scorsese. “He was a marvellous, but very crotchety old man. I remember the first time I called him to do the picture. He said it was impossible, he said he was very busy, and then asked what it was called…”

The final woozy sax score is by turns soothing, searching and menacing, accompanying Travis on his journey through the underworld of New York and to the black spaces inside his own mind.

“Working with [Bernard] was so satisfying that when he died, the night he had finished the score, on Christmas Eve in Los Angeles, I said there was no-one who could come near him,” Scorsese remembers. “I thought his music would create the perfect atmosphere for Taxi Driver.”

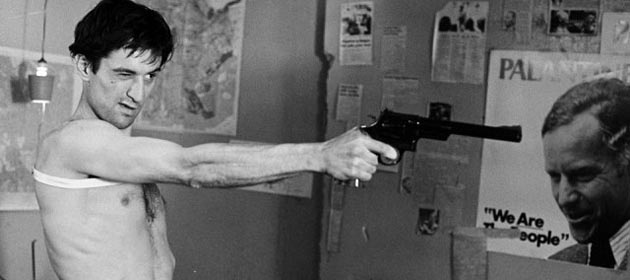

The Cameo

Scorsese appears in the film on two occasions. The first is a Hitchcock-like spot, watching Betsy as she walks into her office in a slow-motion tracking shot narrated by Travis.

The second is more memorable and disturbing, as the jilted passenger who sits in the back of Travis’ cab and fantasises about shooting his cheating wife. Scorsese gave himself the part when the actor originally cast fell ill.

“I was very much influenced by a film called Murder By Contract, directed by Irving Lerner,” he says. “It gave us an inside look into the mind of a man who killed for a living, and it was pretty frightening. I had even wanted to put a clip of it into Mean Streets, the sequence in a car when the main character describes what different sizes of bullet do to people, but the point had already been made. Of course, you find that scene done by me in Taxi Driver.”

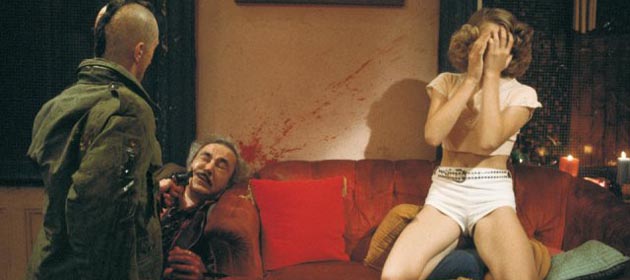

The Violence

The film’s bloody climax came close to earning it a box office-death ‘X’ certificate. Phillips remembers Scorsese feverishly threatening to murder a Columbia executive who demanded edits, before relenting and de-saturing the colours of the film’s final scenes.

Even so, the public reaction was a surprise to the director when the film was released. “I was shocked by the way audiences took the violence,” he says. “I saw Taxi Driver once in a theatre, on the opening night, I think, and everyone was yelling and screaming at the shootout. I didn’t intend to have the audience react with that feeling. ‘Yes – let’s do it! Let’s go out and kill.’”

“Godard once said that all great movies are successful for the wrong reasons,” Schrader ruminates. “And there were a lot of wrong reasons why Taxi Driver was successful. The violence in it really brought out the Times Square crowd.”

The End

Before the film’s release in February 1976, the cast and crew weren’t sure if they had a hit. But they were sure they’d made a great film.

“I remember the night before it opened we all got together and had dinner,” says Schrader. “We said ‘No matter what happens tomorrow we have made a terrific movie, and we’re damn proud of it even if it goes down the toilet.'"

He needn’t have worried. The lines at his local New York theatre stretched around the block, and the film went on to earn a very sizeable $28 million. In May that year, the film went to Cannes. On the way to the festival Schrader met Robert Bresson, a filmmaker he admired greatly. “He asked me, ‘Do you think your film will win the big prize?’ I said, ‘Yes.’” He was right.

The Aftermath

Taxi Driver became the foundation for several successful careers, showcasing the urgent talent of De Niro, Scorsese, Schrader and young Jodie Foster in particular. De Niro’s famously improvised mirror taunt – “You talkin’ to me?” – is one of the most quoted lines in cinema.

But other aspects of the film’s influence were less welcome. Having initially drawn on the actions of gunman Arthur Bremer, the film would go on to inspire further real-life violence. In March 1981, John Hinckley Jr., who had developed an obsession with the film and Foster in particular, attempted to assassinate president Ronald Reagan in a bid to impress the actress.

Schrader guessed the connection straight away. “I was scouting locations in New Orleans. It came over the radio that a white kid from Colorado had made the assassination attempt. I said to the driver, 'It was one of those Taxi Driver kids.'”

It transpired later than Hinckley Jr. had been in touch with Schrader’s office before the shooting, asking for a way to contact Foster. Schrader denied this to the FBI at the time. “I would be fucked, my secretary would be fucked,” he explains. “We'd have to be endlessly answering questions about a letter we've thrown out and don't remember. So I just said, 'No.’”