The making of The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past

Nintendo's Takashi Tezuka and Kensuke Tanabe reveal the hard work that went into this legendary SNES classic

When you look back at the history of the series, The Legend Of Zelda occupies a funny space in Nintendo's planning processes. If a Zelda game arrives in time for a console launch, it's because the game was heavily delayed on the previous generation of hardware. Yet Zelda is never overlooked when a new Nintendo console is being planned – in fact, it's often one of the very first things considered for a new machine.

Our first look at The Legend Of Zelda: The Wind Waker came before the GameCube had hit the shelves, but the game launched over a year into the life of the machine. A demo of what would eventually become The Legend Of Zelda: Ocarina Of Time was shown to attendees of Nintendo's Shoshinkai 1995 expo, but the game didn't materialise until 1998. The title that started this tradition was The Legend Of Zelda: A Link To The Past, the game that marked Link's move off of 8-bit platforms.

Two worlds

In planning the launch of the 16-bit SNES console, Nintendo identified two basic software needs: new properties that could demonstrate the power of the new hardware, and more of what had made the NES successful. For the former category, Nintendo chose racing and flight games that would be impossible to achieve on rival consoles, and delivered a one-two punch of F-Zero and Pilotwings in November and December 1990. For the latter, Nintendo chose to immediately develop follow-ups to its most popular NES properties – the Super Mario Bros and The Legend Of Zelda series.

However, creating a new Zelda was a bit more difficult than creating another Mario game - Mario games were all very similar, but The Legend Of Zelda and Zelda 2: Link's Adventure were very different games. This left the Nintendo EAD team with some big decisions to make regarding its approach to the new game.

"In Zelda 2: The Adventure Of Link, we wanted to include sword combat with a variety of different moves into the gameplay, and so decided the project would use a side-scrolling view that made use of our experience from Super Mario games," explains Takashi Tezuka, a veteran Nintendo developer who served as director for both The Legend Of Zelda and The Legend Of Zelda: A Link To The Past. "We made two Zelda games for the NES, both making the most of that hardware. But then with the next Zelda for the SNES, we were able to add even more new things to the gameplay."

The final decision on which structure to use was driven by the concept of the game, according to Tezuka: "When we were starting the project, we experimented to see if it was possible to include a multi-world structure into the game. Our plan was that events in the hub world would have an effect on the other, overlapping worlds," he explains. "We decided it would be best for us, the developers, as well as for players to have this as two worlds. We felt the best way to represent this overlap of light and dark, and to represent the changes between them, was to use the same slanted top-down view used in the original The Legend Of Zelda game."

New features

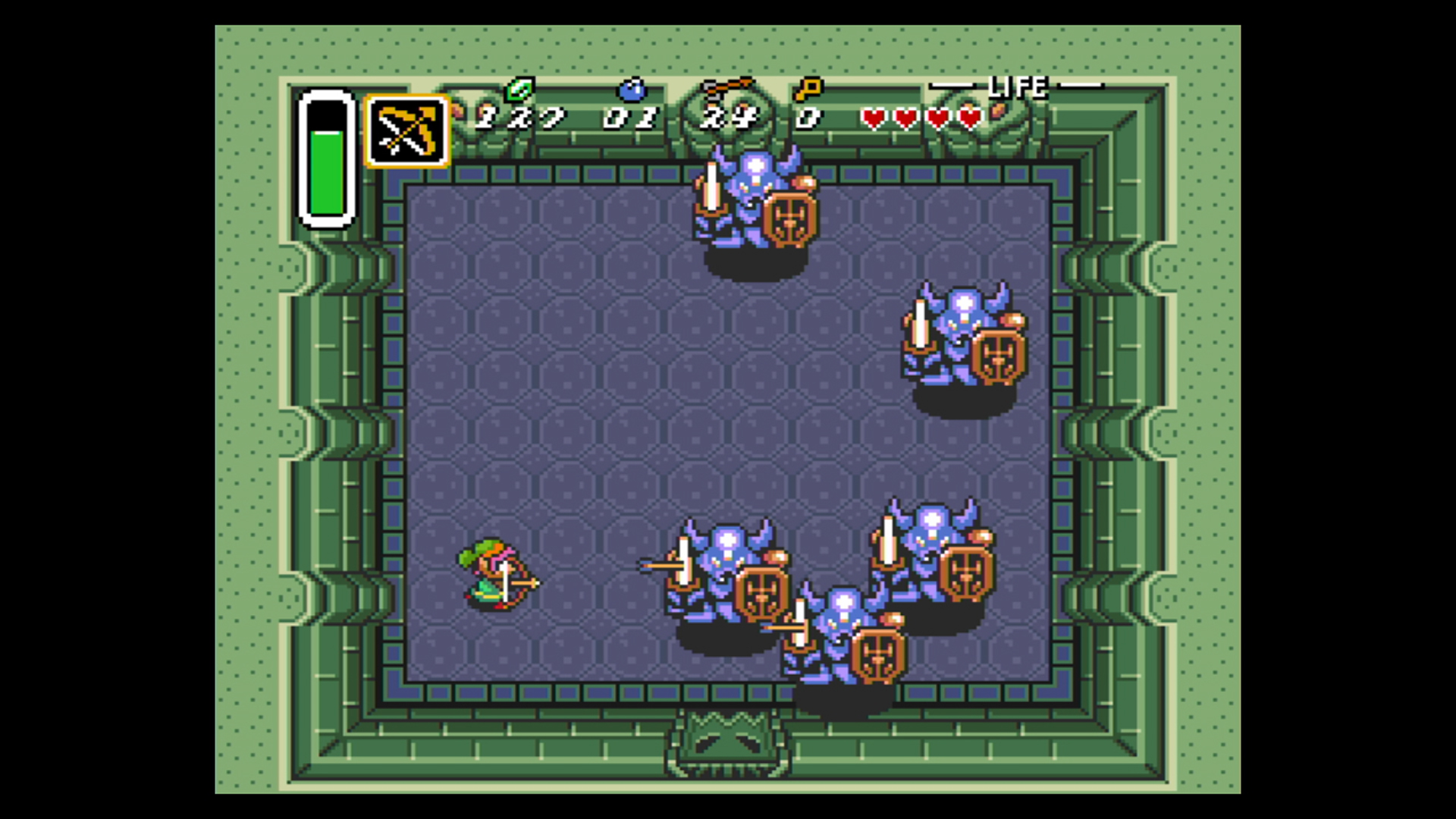

It's rare for a company to discard the major changes made to a sequel, but it would prove to be a wise decision. Quite apart from the fact that Zelda 2 has become known as one of the weaker games in the series as time has passed, there was still a lot that Nintendo could change and improve in going back to the old top-down format. Even very basic things were overhauled, such as the way Link moved around the environment - for the first time, he was able to move diagonally as well as in the four cardinal directions. Rather than using a simple thrust, Link would actually swing his sword in a more realistic arc.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

According to a 1992 Famitsu interview with Miyamoto, this combo of new features actually gave way to another new feature. With the addition of diagonal movement, the Nintendo EAD team had made the logical assumption that Link should be able to attack diagonally, too. However, in practice it made the controls feel somewhat worse, and Link was once again saddled with the ability to move in eight directions but face only four. Undeterred, the team found a way to add a multi-directional attack in the form of a spin attack, activated by holding the sword button down for a couple of seconds. This elegant solution would go on to feature in many subsequent Zelda games and become a staple of the series.

Other changes to the use of weaponry and items were considered too, according to Tezuka. "At the start of development, we wanted players to be able to freely choose which weapons to hold, not just the sword and shield," explains the game director. "We also thought about having these weapons combine, say, for example, having the Bow & Arrows set to the A Button and a Bomb to B Button so that when you use them together (i.e. press both the buttons), Link would shoot an arrow with a bomb attached." This would have revolutionised Zelda's combat system, but ultimately didn’t come to pass - however, it might sound familiar to fans of the series. "In the end, we didn't use this in A Link To The Past, as Shigeru Miyamoto requested that Link always have the sword equipped," Tezuka recalls. "We were able to implement this system in the next title, Link’s Awakening, though."

The SNES

Working with the SNES also opened up a world of new possibilities for the team. "The hardware allowed us to do things we hadn't been able to until that point. I’d only been drawing four-colour pixel images up until then, so even simply just increasing the number of colours available to use to 16 or 256 colours, as well as being able to use high-quality sounds, was really exciting for me," explains Tezuka.

"Figuring out how best to effectively reflect the features of the hardware into a game is always a challenge that Nintendo’s game designers face, and not limited to this game," notes Kensuke Tanabe, the scriptwriter for A Link To The Past. "For me, who'd studied visuals at university, being able to use two 'animation cells' and having the possibility to scroll them separately was a huge deal."

The technique that Tanabe refers to above is that of using multiple background layers. On the NES, it was only possible to draw a single layer of background graphics and a single layer of sprite graphics. With the SNES, developers had the luxury of multiple background layers. For example, in A Link To The Past, one layer is used to display the stage layout and a second layer is reserved for special effects. A third layer is used to display the HUD, which never moves.

The fascinating, complex and generations-spanning history of The Legend of Zelda

"Using it allowed us to create the raining scene at the very start of the adventure, as well as show sunlight filtering down through the leaves in the forest," Tanabe recalls of the special effects layer. "It's the effect of the sunlight in the forest that I'm particularly fond of. I’m also really pleased that we were able to display which floor a player is on by using two 'animation cells'. This was actually a suggestion from the engineering team."

Despite the new possibilities, technical issues were rare. "Our designers had a pretty good idea of what could be done on the hardware back then, so I don't believe we had any unexpected implementations," Tezuka confirms, though he does note one important exception. "Having said that, though, we had a long battle with the memory size, and I remember that the engineering team worked extremely hard to optimise it."

Prior to The Legend Of Zelda: A Link To The Past, all of Nintendo's first-party SNES games had used a minimal ROM size of just four megabits. Not only did the new Zelda require eight megabits of storage, it was pushing that limit. A simple graphical compression routine was brought over from Super Mario World to combat this, which saved space by limiting many graphical tiles to eight colours, rather than the standard 16 that the SNES is capable of.

With data duplication cut to an absolute minimum, the game was able to fit into the ROM allocated. Even then, translating the game from Japanese once again challenged this limit. In his 1992 Famitsu interview, Miyamoto explained that the original plan was to use a higher capacity cartridge for the translated game, and use what extra space remained afterwards to make some improvements to the Western releases. However, further compression rendered increased capacity unnecessary.

A different story

The 16-bit versions of both Mario and Zelda had entered development at the same time, but while Mario stuck to its planned trajectory and made it out for the November 1990 launch of the console, Zelda’s planned arrival in March was going to be impossible. In fact, by the time eager gamers in Japan were trying out the new Super Famicom for the first time, Nintendo EAD was only just confident of the game system it had settled upon! The next step was to add additional staff to complete the work by adding in enemies, a scenario and more.

In an interview for the official Super Mario World guidebook in Japan, Miyamoto estimated that the game would be completed by Children's Day (May 5th) in 1991 in anticipation of a summer release, but this turned out to be an underestimation. According to Miyamoto's 1992 Famitsu interview, implementing these final features took about eight months, pushing the game back further from summer to winter. If there's any reason that A Link To The Past took longer than expected, it might well be because of how much attention was paid to the plot of the game. Right from the start, it was clear that it would be told in more detail and with greater dramatic flair than the NES Zelda games were capable of, and that item acquisition would be closely tied to story progression.

A clear example of this comes in the game's opening sequence - by contrast to the earlier games, the SNES game offered a far more structured introduction to Link's quest. "In A Link To The Past, the game starts with a dark, rainy scene, with Link being just a regular village boy who, in the same situation as the player, doesn't really know what's going on, but just follows Princess Zelda's voice and works to save her. However, in doing this he somehow ends up becoming an outlaw. We wanted players to start feeling excited and wonder what will happen next," explains Tezuka.

It's a dramatic opening, but finding and rescuing the princess so early on surprised some players, who felt that the game was going to end suddenly. "We didn’t intend to make players feel like the game was going to end there," admits Tezuka, who always saw Link's ascension to heroism in a rather different way. The previous games had just dropped the player into the world and allowed them to get on with it, but this would not be an approach that would be repeated in A Link To The Past.

"We didn't have Link start out as a sword-wielding hero right from the start, because we had already decided at the beginning of the project that we wanted him to awaken as a hero when he pulls out the Master Sword," explains Tezuka. "We did make a number of adjustments to the placement and ordering of the weapons and items so that we could get the ideal flow for the game, no matter the player or playstyle," he continues. Instead of starting out as a bonafide hero, Link would acquire a variety of items over the course of the game and experience his development naturally. "We thought that players would form an emotional connection with Link as they play and by the time he ultimately becomes a hero, it would just be natural that he can use a variety of different weapons," Tezuka confirms.

The Master Sword

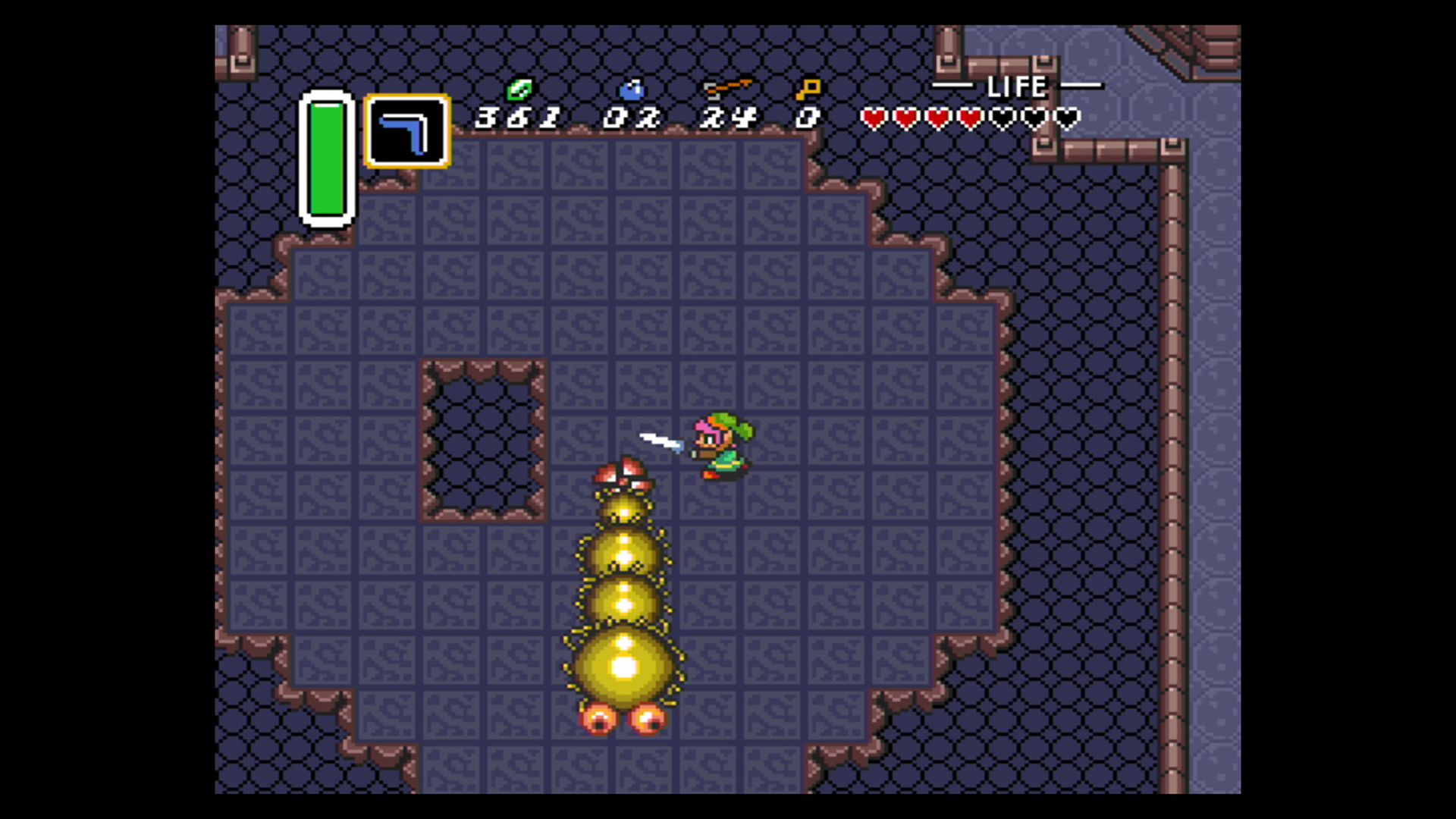

The most memorable weapon to be introduced in A Link To The Past was the Master Sword, a weapon that has endured over the decades as a key piece of the Zelda mythology. As Tezuka alluded to earlier, the scene where Link obtains this blade was one of the most crucial parts of the project. "Kensuke Tanabe had an idea for a truly memorable hero-awakening scene when we started this project," recalls the director, crediting the scriptwriter.

"In the midst of a forest, with light filtering down through the leaves, the sword stood waiting for someone worthy of wielding it to arrive. Link draws the sword out as the light trickles through the leaves. "In order to draw the sword, one needs to have both inherited the blood of the family of knights who protect Princess Zelda, as well as possess the three pendants. From the moment Link pulls the sword out, it recognises him as a hero, and grants him its power," says Tezuka, with his accurate recall of the plot standing as a testament to the importance with which it was treated. The Master Sword was also given its mythological importance at this early stage, as Tezuka recalls, "We also decided then that the Master Sword was a sword that alone holds the power to repel evil, and I suspect this is why it continues to carry such an important role in the rest of the series."

However, the Master Sword scene isn't just symbolic. "It's at this point that the game's real battle starts," the director notes. "Our main aim was to show the birth of a hero in a scene fitting of The Legend Of Zelda, and overlap this with a sense of achievement for the player that they have been recognised as a hero after having overcome many challenges." Instead of being a moment of triumph, it's a turning point which ultimately leads to the introduction of the game's dual-world concept. "What we had decided on from the start was that Link would first become a hero in the Light World and defeat the first boss," says Tezuka. "From that point is when his battle to defeat the real enemy, Ganon, in the Dark World begins."

Lasting influence

The Legend Of Zelda: A Link To The Past was released on 21 November 1991 in Japan, with North American and European releases following on 13 April 1992 and 24 September 1992 respectively. No matter where you were in the world, the game was regarded as a classic. Critical praise was unanimous - Computer & Video Games awarded the game 89%, noting that "the elements of strategy and adventure are added treats rather than annoying extras." A review in Mean Machines scored the game 95% and declared it "simply the greatest exploration/adventure game available for a console," while Super Play Gold's 93% review noted that "you're unlikely to want to switch the game off".

The game sold a massive 4.61 million copies on the SNES, and ultimately spawned both a successful re-release on the Game Boy Advance as well as a successor for the Nintendo 3DS, The Legend Of Zelda: A Link Between Worlds. Despite the excellent quality of A Link To The Past, it would ultimately prove to be the end of the line for the Zelda series as players had known it, as the series was about to undergo a radical change. The next home console sequel was The Legend Of Zelda: The Ocarina Of Time, which transformed the series with open 3D spaces and more.

While smaller 2D Zelda games would continue to appear on the Game Boy platforms, including the excellent Link's Awakening, Oracle Of Ages /Oracle Of Seasons and The Minish Cap, there was never another 2D Zelda game to get the big-budget treatment that A Link To The Past received. But that's not to say that A Link To The Past hasn't had a lasting influence, not by a long shot. Elements from the game including the spin attack, the Hookshot and the Master Sword have become series regulars, and that dual-world concept has been revisited very frequently – just look at young and adult Link in Ocarina Of Time, or human and wolf Link in Twilight Princess.

The third Zelda game is as tightly woven into the legacy of the series as any of the other major entries. Ultimately, The Legend Of Zelda: A Link To The Past is one of those rare games that not only achieved critical and commercial success, but has stood the test of time and continues to attract new fans today. How does the team feel about this sustained success? "We're truly thankful, and consider it a great privilege," Tezuka says, but he's careful not to rest on his laurels. "At the same time, it also drives us to create new games that will surpass this acclaim."

Keep up to speed with all of our celebratory Zelda coverage with our The Legend of Zelda celebration hub

Nick picked up gaming after being introduced to Donkey Kong and Centipede on his dad's Atari 2600, and never looked back. He joined the Retro Gamer team in 2013 and is currently the magazine's Features Editor, writing long reads about the creation of classic games and the technology that powered them. He's a tinkerer who enjoys repairing and upgrading old hardware, including his prized Neo Geo MVS, and has a taste for oddities including FMV games and bizarre PS2 budget games. A walking database of Sonic the Hedgehog trivia. He has also written for Edge, games™, Linux User & Developer, Metal Hammer and a variety of other publications.