The Story Behind Cannes

If it's scandal, glamour and great films you're after, Cannes do

It's only a few weeks until the 63rd Festival De Cannes kicks off with the world premiere of Sir Ridley and Russell's Robin Hood .

It's the perfect opening night film, of course, and not only because of it kicks things off with all the high-wattage glamour Hollywood can muster. The film's story, too, captures the Cannes sensibility perfectly.

An agent provocateur whose scandalous antics upset the status quo? A gentleman thief robbing fromthe rich to make everybody's life a little better? A creative underdog mixing bold techniques and distinctive visual imagery?

See, right from the start, the history of Cannes has always been a combustible mix of politics, commerce and art.

Here, then, is Cannes opened - the personalities, the memories and the downright mental moments that have been this sleepy French seaside town second only to L.A. as the movie world's place to see and be seen.

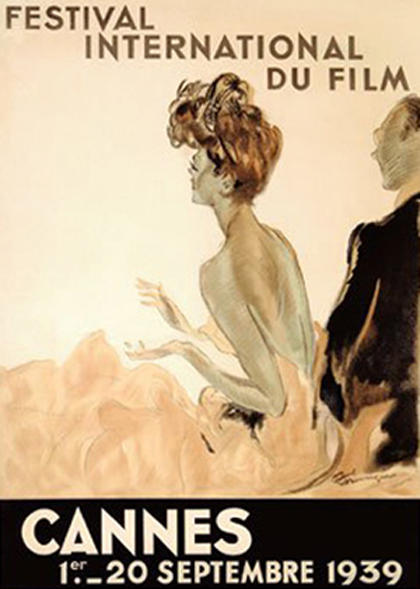

1930s & 1940s - Beginnings

The Cannes Film Festival started, as most things do, because of politics.

Sign up for the Total Film Newsletter

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

The French were outraged that the 1938 Venice Film Festival awarded top prizes to Leni Riefenstahl's Fascist propaganda flick Olympia , rather than Jean Renoir's anti-war La Grande Illusion .

So later that year, the French Government signed off on plans to host an international film festival on its own soil, after extensive lobbying by a group that included the surviving Lumiere brother, Louis.

The small seaside town of Cannes was chosen for its climate - and the willingness of the local authorities to help pay for it!

The perfect idea, the perfect location...and a terrible start date: 1st September 1939. Yup, the day Germany invaded Poland and kicked off World War Two.

The inaugural Festival was quickly curtailed and the champagne put on ice until after the war. But, as Inglourious Basterds proved, the French really love their cinema, so the first Festival proper was held in 1946.

An instant success and its prestige was apparent with screenings of the latest by Hollywood titans (Hitchcock, Wilder) and Europe's finest (Cocteau, Rossellini).

But stuttering early steps saw the 1948 and 1950 events cancelled due to budgetary constraints. Cannes was not - yet - the industry's premier event. However, thatwas about to change.

Scandal!

Getting things sorted behind the scenes was controversy enough in these early days. But bear with us, things get positively shocking, shoon enough.

The Winners

The 1946 judges went crazy, awarding the top prize to 11 films, most notably Wilder's The Lost Weekend , David Lean's Brief Encounter and Rossellini's Rome Open City .

By 1949, that enthusiasm had settled down enough to give the Grand Prix to a single entry, starting well with Carol Reed's classic The Third Man .

Next: 1950s - Success & Sensation [page-break]

1950s - Success & Sensation

Cannes as we know it today was created largely during the 1950s. Crucially, the event moved to the Springtime, away from rival festivals, to claim a part of the calendar for itself.

Then, in 1955, the Grand Prix was replaced with the iconic Palme D'Or, modelled on Cannes' ubiquitous palm trees. And, most importantly, the Croisette became the place to be seen.

A then-unknown, not to mention brunette, Brigitte Bardot caused a stir in 1953 by lounging on the beach wearing just a bikini.

The following year, Simone Sylva went one better by foregoing even the bikini - much to Robert Mitchum's mock-horror.

Scandal!

Look beyond the flesh, and already the young festival was at war with critics feeling that the organisers had got this or that detail wrong.

The most vocal was young upstart Francois Truffaut from Cahiers Du Cinema, got showed up in '58 despite getting himself banned. The festival is doomed, he declared...

...before promptly proved himself wrong the following year by bagging the Best Director prize for his filmmaking debut, The 400 Blows .

The Winners

Alf Sjöberg becomes the first director to win a second top prize, athough given that his first was one of 1946's 11 winners, it's probably cheating.

Other notable winners included Orson Welles for Othello , Henri-Georges Clouzot for The Wages of Fear and Delbert Mann for Marty.

Next: 1960s - Internationally Iconic [page-break]

1960s - Internationally Iconic

In 1959, a bunch of canny entrepreneurs came to Cannes to wheel and deal their latest films; by 1961, the Marche Du Film was an official part of the Festival, and a shady parallel world sprang up alongside the glamour and prestige of the art-house crowd, as every man and his dog came from around the world to sell their wares.

Cannes underlined its credentials as the industry's prime developer of talent, bolstering the central competition with side-events like the International Critics Week (started in 1962) and the Directors' Fortnight (1969).

The more international perspective was enhanced when, in 1960, Belgian crime author Georges Simenon became the first non-Frenchman to head the jury. Fritz Lang, Sophia Loren and Luchino Visconti followed, establishing Cannes' rep for letting the biggest names judge their peers.

But there remained a corner of the Festival that remained uniquely French. In 1968, in solidarity with nation-wide strikes and the sacking of the head of the Cinémathèque Française in Paris, the Nouvelle Vague gang (including, yes, Francois Truffaut) staged a sit-in protest that eventually got the Festival cancelled.

Scandal!

The premiere of Michaelangelo Antonioni's L'Avventura in 1960 started a now seemingly obligatory tradition by provoking the first mass booing; within years, of course,it would be hailed as a masterpiece.

At the other end of the decade, Dennis Hopper, Peter Fonda and Jack Nicholson proved the Americans were peerless when it came to raising hell, as their promotion of Easy Rider descended into drink & drug-fuelled anarchy.

The Winners

Lindsay Anderson's if... captured the tumultous mood of the era in 1969, an apt Palme D'or winner after the '68 Festival's cancellation.

Other notable winners included Federico Fellini for La Dolce Vita , Luis Buñuel for Viridiana and Antonioni (finally getting the ovations denied to L'Avventura ) for Blow-Up

Next: 1970s - Prestige & Perversion [page-break]

1970s - Prestige & Perversion

The big chance here: films in competition now selected by the Festival itself, rather than being sent in by hopeful producers and studios. On a more even playing field, being in competiton was itself a badge of honour, whether the films thrived or died on their arses.

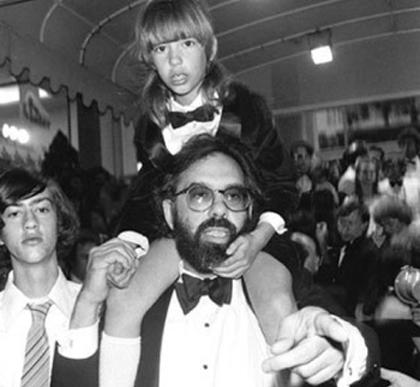

The decade belonged to Americans, with Altman, Coppola and Scorsese making a splash for an exciting new generation.

The emphasis on youth was emphasised by the creation of the Camera D'or award for first feature - which in later years would become a vital launching pad for the careers of Jim Jarmusch, Mira Nair and Steve McQueen.

Scandal!

Cannes' reputation for on-screen shocks was cemented during the 70s, with food & fucking fest La Grande Bouffe (whose cast of gourmands is pictured below) and Japanese art-porn flick In The Realm of The Senses becoming the films critics loved to hate.

Pitch-black material was clearly in vogue, Taxi Driver scooping the Palme D'Or despite jury president Tennessee Williams railing against the "brutalising experience" of on-screen violence. "Films should not take a voluptuous pleasure in spilling blood and in lingering on terrible cruelties as though one were at a Roman circus."

The Winners

Francis Ford Coppola achieved a rare double-success, bagging two Palme D'Ors within five years for both The Conversation and Apocalypse Now .

Other notable winners included Altman for M*A*S*H , Scorsese for Taxi Driver and Volker Schlöndorff for The Tin Drum .

Next: 1980s - Conspicuous Consumption [page-break]

1980s - Conspicuous Consumption

The Festival super-sized with a move into the purpose-built Palais des Festivals, still its home today. Carping critics referred to it as "the bunker," which seems a perfectly sensible name for a dimly-lit building isolated from the craziness going on outside.

With the upscaling came increased bling - 24 (count 'em) red carpeted steps leading up to the cinema, while the stars were invited to leave their handprints in the clay outside in a sunnier take on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Scandal!

A relatively quiet decade for Cannes, although it was the absence of passion that caused the biggest stir when Charles and Diana arrived in 1987 with no great enthusiasm.

The palpable chill between them, ironically, electrified the British media, sensing for the first time that the fairytale had Grimm undertones, and kickstarting a decade-long obsession into Diana's private lifes that would only end, tragicailly, on another visit to France in 1997.

The Winners

The most famous winner of the decade left it late, as twentysomething Steven Soderbergh snatched a surprise win for sex, lies and videotape to usher in a golden age of U.S. independent cinema.

Other notable winners included Akira Kurosawa for Kagemusha , Wim Wenders for Paris, Texas and Roland Joffé for The Mission .

Next: 1990s - Independents' Day? [page-break]

1990s - Independents' Day?

Soderbergh's win the year before kickstarted a revival of American fortunes with three further U.S. winners in the first half of the decade. The prestige attracted the attention of Hollywood like never before, and Cannes divided in two, the auteurs .

It's not as if Cannes had been starved of lavish blockbuster premieres or smartly-dressed stars before, but L.A. pretty much emptied every May as every star with a movie out hit Cannes as a pitstop on the publicity tour.

If it wasn't Madonna cavorting in Jean-Paul Gaulthier, it was Bruce Willis' consistently embarrassing travails (see below).

The porn industry took full advantage, cannily setting up the Hot D'Or Awards to coincide with the Festival to hitch a ride (so to speak) on the free publicity.

Scandal!

If there was an abiding image to 1990s Cannes, it was the 24-carat comedy of egos exploding, as Cannes' competitors - possibly in an over-zealous attempt to show their artistic zeal - threw their toys of their designer prams.

Lars Von Trier, having missed out on the Palme D'Or for Europa , called jury president Roman Polanski a midget and refused to accept the prize he felt he'd been fobbed off with.

Harvey Weinstein, not to be outdone, launched into a tirade against Cannes' "elitism and its predilection for dull, irrelevant films. There's something wrong with Cannes, and it needs to be fixed." Probably by giving all the prizes to a Miramax film.

As for Willis, having started the decade with appearances in Cannes faves The Player and Pulp Fiction , suddenly realised that his sci-fi action flicks weren't getting quite the same reception as he tetchily took on critics who laughed at his death scene in Armageddon .

But his most memorable moment came when one of the original four elements decided it had had enough of Willis:

The Winners

Quentin Tarantino rode the Zeitgeist all the way for Palme D'Or glory with Pulp Fiction , literally flashing a finger at the art-house intelligentsia.

Other notable winners included David Lynch for Wild At Heart , The Coen Brothers for Barton Fink and Mike Leigh for Secrets and Lies.

Next: 2000s & Beyond - Cannes-Can [page-break]

2000s & Beyond - Cannes-Can

Into the new millennium, and Cannes continued to innovative, establishing the Producers Network and Short Film Corner to promote often overlooked wings of the film industry.

Otherwise, it's been business as usual. The Hollywood behemoths dazzle with their razzle: Revenge of the Sith , The Da Vinci Code , Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull in the past few years alone.

Meanwhile the juries - headed by, amongst others, David Lynch, Quentin Tarantino and Sean Penn - cement the rise of new waves like South Korea and Romania and resurgent genres like the documentary.

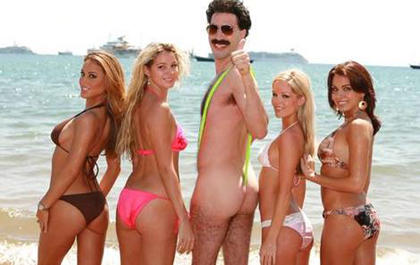

And somewhere in the middle, a Kazakhstani journalist rocked up wearing just a lime green mankini.

Scandal!

Taboos came to Cannes to be summarily executed, with audiences' stomachs churned into oblivion by Irreverisble and Antichrist's hardcore sex 'n' violence.

But the most dispiriting trend of the decade was seeing great hopes crash and burn in the limelight: Richard Kelly's Southland Tales , Vincent Gallo's The Brown Bunny , and Sofia Coppola's The Virgin Suicides , all bombed amidst a barrage of boos.

The Winners

Michael Moore's Fahrenheit 9/11 became the first documentary to win the Palme D'Or in a pointed rebuke against the Bush administration. Clearly, Cannes hadn't quite lost its political heart amidst the pap-snapping frenzy.

Other notable winners included Roman Polanski for The Pianist , Ken Loach for The Wind That Shakes The Barley , and Michael Haneke for The White Ribbon .

The Future

Cannes 2010 brings a hip-but-respected jury head in Tim Burton, big premieres (the afore-mentioned Robin Hood) , and an intriguing selection of movies in competition.

Cannes favourites (Mike Leigh, Jean-Luc Godard and Abbas Kiarostami) will be duking it out with curveball choices - could Doug Liman win a Palme D'Or? - and wildcard wonders: who knows what Chad director Mahamat-Saleh Haroun's A Screaming Man will be like?

Future Scandal!

Early days, but with Takeshi Kitano back with a return to gangland, he's the best bet for on-screen shocks. Off-screen, boobs falling out, blows being traded: Cannes has seen it all, so best just to sit back and enjoy it.

Future Winners

A useful rule of thumb is that, eventually, all Cannes faves will find their way to shaking hands with the golden palm.

So a good bet this year is revered Thai auteur Apichatpong Weerasethakul, a Jury Prize winner in 2004 and whose odd-sounding Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives might find favour with Tim Burton.

As for the coming decade, you can count on Pedro Almodovar and Wong Kar-Wai, winners of minor prizes in previous years, coming up trumps. Britain, too, has a major contender in Andrea Arnold: both of her features to date have seen favour with Cannes juries.

There here hasn't been an American winner since 2004, so place odds on one emerging soon. Maybe it'll be Paul Thomas Anderson (Best Director in 2002 for Punch-Drunk Love ); maybe, like Steven Soderbergh, it'll be somebody we haven't even heard of yet.

But the the best advice is to just keep looking towards the Cote D'Azur. Clearly, that's still where it's at.

Like This? Then try...

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter here .

Follow us on Twitter here .