GamesRadar+ Verdict

Pros

- +

Hugely imaginative world

- +

A real sense of carving your own path

- +

Colour gimmick works well

Cons

- -

Not very welcoming beginning

- -

Refilling and draining can become tiresome

- -

Combat is a touch unsatisfying

Why you can trust GamesRadar+

PC gamers appreciate strange games. We’ve got the same big names as the other platforms, but we also have some truly fascinating stuff that exists below the mainstream. The Void exists there, a strange, often baffling game about a place beneath dreams, where colour is your commodity and your lifeforce. It deserves to push up into the real world.

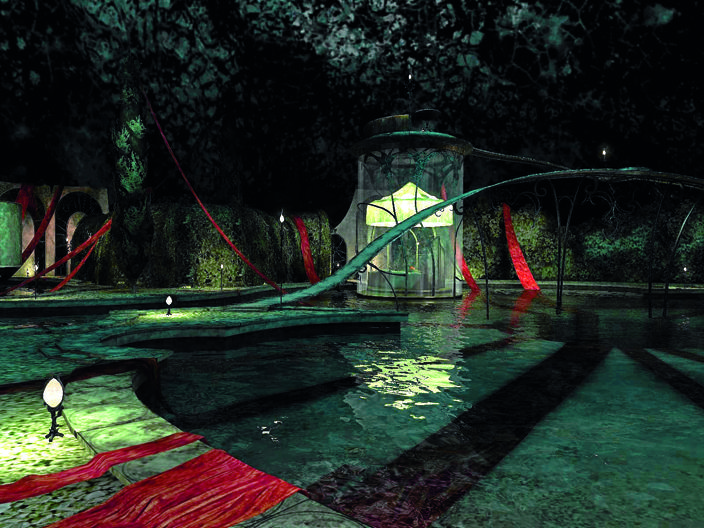

So hold tight. This is going to get strange. In The Void you play as a transparent soul. Not that you’re told why or how you’re here. Everything in the game reflects this uninformed introduction: the first-person view feels immediately limiting, mouse-look auto-set to skittish. You’ll feel nervous from the beginning. Nor will you have much idea of what’s going on by the end: there’s no explicit endgame to work towards. After playing, you can infer that the Void is a form of purgatory – characters make reference to the fact that your body must have died, but question whether it would be able, or even want to, support your soul once more. The only splashes of brightness in this peculiar realm come in a visceral form – colour.

Colour is the key to existence in the Void. Interaction with any aspect of the Void is impossible without splashing strokes of colour around: discussions with other characters are initiated by chucking paint over them. Colour is flung via fiddly mouse-drawn ‘glyphs’, they also enable actions and a few special powers, varying from a simple speed-boost to a ‘harpoon’ that can be fired into squishy points in rock-faces. While these powers are useful to a point, you’ll find yourself neglecting some of the more minor choices open to you: the speed boost, for example, provides such a limited effect that you might as well press on at average pace.

Tiny sprouts of colour grow from the otherwise barren ground – collecting these with a tap of the right mouse button fills chambers on the right-hand side of your screen. Here, colour is stored, safe until you choose to use it. To affect the world, this colour must be taken to the left side of the screen – this can only be done by passing the colour through the ventricles and arteries of ‘hearts.’ These hearts are plugged into your incorporeal form, and manually filled from colour reserves collected from the ground. Your body, therefore, is a refinery, collating and processing specks of loose colour, allowing you to amend the Void. But this process is toxic – as your colour is turned into malleable ‘Nerva’, which is able to be deployed in glyph form, it’s drained from your body, taking you closer to death.

As a game device, refilling and draining your hearts manually can become tiresome, but it does perpetuate the idea of the tenuous foothold your character has in the Void. Conserving the last pixels of colour to make it through to the next day cycle, and the next harvest of colour, is a truly tense experience. It’s easier to forgive time-consuming game mechanics when they’re so clearly rooted in maintaining the atmosphere the game has worked so hard to cultivate.

But it’s more complicated than simply staying alive. The game’s hub world is laid out as a biological system, with muscular central chambers and fleshy nodules leading off from them. Dwelling in these chambers are sisters – beautiful women, reclining in various states of undress, waiting for your arrival in their world, and gifts of colour.

More info

| Genre | Adventure |

| Description | As a game, The Void demonstrates that the PC is the most exciting gaming platform. Independent in development, game mechanics and spirit, this creative adventure title simply wouldn’t work anywhere else. |

| Platform | "PC" |

| US censor rating | "" |

| UK censor rating | "12+" |

| Release date | 1 January 1970 (US), 1 January 1970 (UK) |