There's one clever feature in HBO's The Last of Us that I wish was in the games

The way HBO's The Last of Us sidesteps my biggest video game bugbear is pretty genius

The devil's in the details, so goes the age-old adage. This was always going to be one of HBO's biggest hurdles when adapting The Last of Us for television. Because it's one thing acquiring top writers, the perfect cast, and the budget to produce the most cutting-edge CGI effects and real-world set dressing, but another thing entirely taking cherished source material, transporting it across mediums that aren't always compatible, and attempting to appeal to a mass audience. On a micro level, the fact that I've now got my non-gamer, zombie show-averse mother texting me as soon as the credits roll every week suggests that transition has been a successful one.

On a much wider scale, the very fact that people who'll never play Naughty Dog's epic adventures in video game-form are now getting to experience Joel and Ellie's rollercoaster story is pretty wonderful. Everything is new to these folk, meaning every narrative twist and turn has scope to shock and awe. For everyone else familiar with the games, the show's so far near-perfect blend of deferential lip-service and subtle tweaks to the familiar formula have kept us hooked – not least in relation to how the cordyceps virus is transmitted, the fate of one key character early doors, and episode 3 in, well, its entirety. With the former in mind, it's a change to the makeup of the virus, how it's spread, and how the infected interact that I've fallen in love with. So much so, that I wish it was part of the games themselves.

Sink your teeth

The Last of Us Part 1 review: "A remake of exceptional craftsmanship and creative restraint"

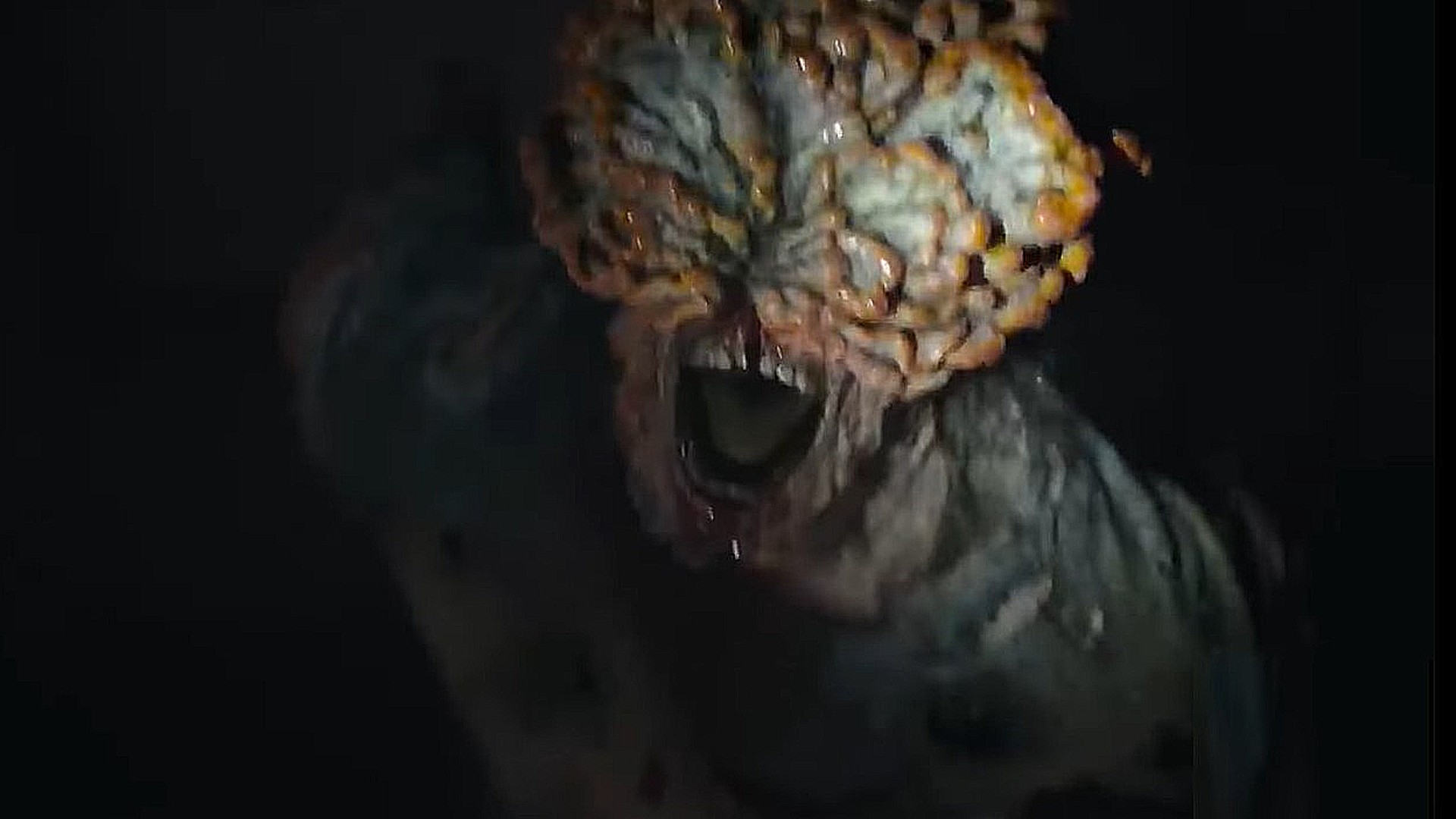

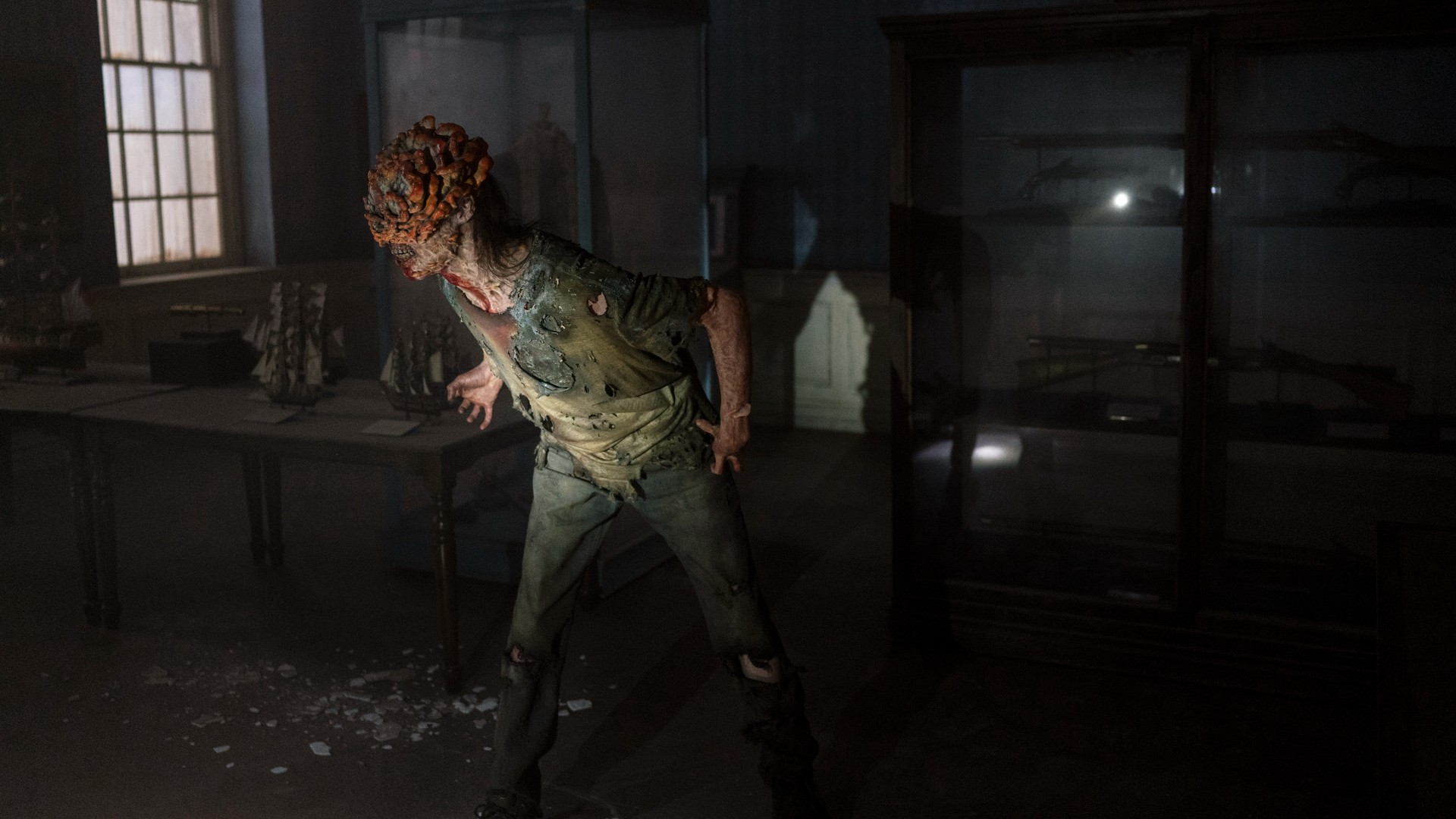

In HBO's The Last of Us the cordyceps virus is no longer airborne, as was the case in the video games. Instead, the parasitic fungus consumes hosts from within, taking control of their bodies and, eventually, their minds – a process best illustrated by the infected older woman in the first episode's flashback outbreak sequence; as well as that twisted kiss scene at the end of episode 2. At this stage in the show, clickers biting humans appears to be the most common means of infection still, but breathing in deadly spores in pent up areas is no longer a threat.

From a practical standpoint, this makes sense. Being forced to equip and remove gas masks at a steady rate, as per the games, would surely break immersion in the TV show, and could compromise the tension it's done so well to sustain so far. Part of what makes the show both so endearing and engaging is the growing relationship between Joel and Ellie which is, of course, steered by the stellar acting of Pedro Pascal and Bella Ramsey. Body language, facial expressions, tone, pitch, rapport – all of these things become especially important in lieu of the interactive properties of video games, therefore removing any unnecessary barriers is a shrewd move.

An extension of this decision is reflected in how the infected communicate with each other. Like the games, clickers become blind after time, eventually becoming reliant on sound to track their prey. We see this for the first time in episode 2 when Joel, Ellie and Tess reach the museum, when things go awry after Ellie blows their cover. Prior to this scene however, unlike the games, we're shown how the tendrils of grounded clickers grow into the earth – whereby a network of plant-like roots connects the infected across huge distances, again by way of vibration and sound. At one point, Joel shoots an aggressive clicker near the museum, which alerts a horde of others elsewhere to his exact location.

It's a cool twist on the source material that I think would've worked really well in the games. Enemies magically knowing my exact location is one of my biggest bugbears in games across the board, and while the Last of Us is far from the biggest offender in this space, I do remember losing the rag more than once in the first game. The flooded tunnels; when the floor collapses in the university; and that bit when you kick start a generator and need to peg it to the floor above and out through a security door – in all of these moments, no matter if you sneak or slink or sprint, enemies can wind up knowing exactly where you are no matter how you play it. It's frustrating and immersion-breaking because it steals autonomy from the player.

Square roots

"But what I find irritating is when a game shows me how to play, gives me the tools to succeed, and then flips the script without context or explanation – it invariably feels unfair, and pulls me out of the moment".

To be clear: I don't have an issue with being stalked by enemies as a means of ramping up difficulty or tension, especially in horror games, and dopey, non-reactive AI can be just as infuriating. But what I find irritating is when a game shows me how to play, gives me the tools to succeed, and then flips the script without context or explanation – it invariably feels unfair, and pulls me out of the moment. If clickers rely on sound to track my location, how come this doesn't apply in the above scenarios? And why can't they hear me choking out their pals, or the thud of their lifeless bodies as they hit the ground mere meters away?

Sign up for the Total Film Newsletter

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

Again, there are plenty of games where this is more of an issue than in The Last of Us, but I was really taken by the roots network idea posed in the HBO show. For me, this circumvents the problem, and I think it'd have been such a cool addition to the games. It'd have made certain parts of the games far more challenging, but at least doing so would have maintained consistency, especially in those moments where you're forced to think on your feet. More than this, this subtle tweak has upped my interest in the show – I'm now keen to see if any other changes make me feel the same way, or vice versa.

In January, Neil Druckmann said, "it’s up to us whether we want to continue it or not", in reference to a potential The Last of Us: Part 3 video game. Now with season one flying, and a second season of the HBO show also confirmed, I'm both interested and invested to see how one might now inform the other in years to come.

Did you know that The Last of Us' Nick Offerman nearly turned down playing Bill on the show?

Joe Donnelly is a sports editor from Glasgow and former features editor at GamesRadar+. A mental health advocate, Joe has written about video games and mental health for The Guardian, New Statesman, VICE, PC Gamer and many more, and believes the interactive nature of video games makes them uniquely placed to educate and inform. His book Checkpoint considers the complex intersections of video games and mental health, and was shortlisted for Scotland's National Book of the Year for non-fiction in 2021. As familiar with the streets of Los Santos as he is the west of Scotland, Joe can often be found living his best and worst lives in GTA Online and its PC role-playing scene.