The time for virtual reality is now

How VR has evolved, and why you should care about its future

This year was the first that I stood in a snowstorm in the middle of June. Behind me, mountains loomed in the distance; ahead stood a giant, castle-like structure of the sort I'd only ever seen in travel brochures. And everywhere I looked, snow. Granted, this scene wasn't actually real, at least not in the physical sense. I was in a cramped demo room during E3 2013, wearing a high-def prototype of the Oculus Rift, navigating a re-creation of the Unreal Engine 4 Elemental demo. Still, flakes fluttered down from the sky, whipping around in the loud wind to create that same blinding blanket of white I've seen every winter for as long as I can remember. The illusion was so convincing, in fact, that it made me think about how much I hate snow.

I walked through the door of the nearby fortress and rotated my head to the left. The tracking system in the Oculus translated that movement into data, and the in-game camera followed suit. Small visual details I'd never paid much attention to before, like the cracks in the walls and the texture of the floor, became far more prominent once they were right there in my face. As did the lava that poured into the room when I entered, sectioning the floor into small islands. Then, a totally unassuming statue of a dark knight came to life in front of me, with lava for eyes and lava for blood, and it stood up, wielding a humongous maul (which, naturally, was dripping with lava).

I had to shift my entire head upwards to take in its intimidating height. It's easy to imagine that, had I actually been in that place--had I physically been standing in that keep, surrounded by lava, with a towering, evil, living statue in front of me--my heart would've instantly exploded into a million pieces. It's one thing to watch that statue come to life from behind the safety of a monitor, but to come face to face with the thing while inside its world is exponentially more intense.

"I think we're at an intersection point in terms of the technology and applications," says Walter Greenleaf, senior research scholar and director of the Mind Division at Stanford University. "It's been a lot longer, the time course, than we all thought back in the '90s, how long it would take for virtual reality to take off--and maybe we're wrong right now that we're at the point where it is about to take off, but I don't think so."

It's perhaps unsurprising Greenleaf and his colleagues were first inspired to pursue VR some 30 years ago by science fiction. From 1982's Tron to William Gibson's Neuromancer novels, more and more works began exploring the exciting possibility of transporting the conscious mind into a world of pixels. The sci-fi stories of the '80s inspired even more VR works in the '90s, including the The Lawnmower Man, that bizarre reboot of Jonny Quest, and even The Matrix trilogy--and people couldn't get enough.

"There was a huge amount of hype, and everybody was very excited about virtual reality. It was on the cover of everything from The Economist to Rolling Stone--and there were a lot of horribly bad movies," Greenleaf jokes.

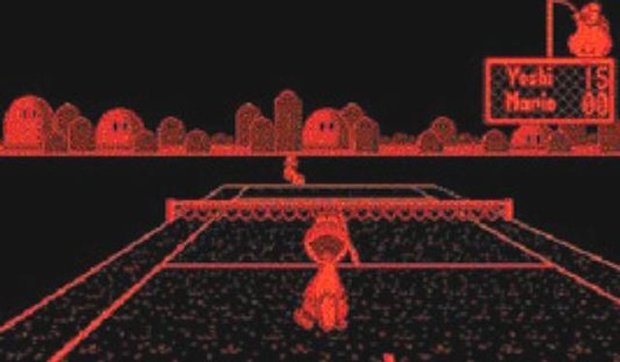

Rudimentary VR gaming experiences, such as the coin-op arcade game Dactyl Nightmare and Nintendo's failed Virtual Boy console, fell short of their sci-fi inspirations. According to Palmer Luckey, founder of Oculus VR, that was because the VR hype of the '90s was based on long-term possibilities, not on what could be accomplished at the time.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

"There's really basic reasons why virtual reality couldn't have succeeded, even if it hadn't been overhyped," Luckey says. "People were excited about what virtual reality could be, not what the reality of it was. If people had come out and said, 'Hey check this out, you can run this really basic 3D demo at a really low framerate in mono,' nobody would've gotten hyped up about that.

"It's really just in the last few years that we're starting to see dirt cheap computer hardware that can render high-resolution environments in 3D at high frame rates. That's required on a basic level for virtual reality--there's no way it could've been possible to succeed in the '90s no matter how well expectations had been managed."

Time is, of course, a great boon for any technology, but some of VR's most significant advances have been fueled by the progress of other industries. Take, for instance, mobile phones. The booming smartphone market has led to millions (billions?) of dollars invested in developing compact, high-resolution displays. That's exactly the type of technology the VR industry needs, considering head-mounted devices need to be lightweight without sacrificing the quality of optics systems.

"The other thing is motion tracking technology has gotten so dirt cheap. I mean, 10 years ago, things you would've spent thousands of dollars on are now in every phone, and the total cost of the parts is under a dollar," Luckey says.

On the next page: the first line-up of true VR games.

Ryan was once the Executive Editor of GamesRadar, before moving into the world of games development. He worked as a Brand Manager at EA, and then at Bethesda Softworks, before moving to 2K. He briefly went back to EA and is now the Director of Global Marketing Strategy at 2K.