Topping the end of the world - where do action movies go when the apocalypse is worn out?

You know that line in The Incredibles, the one about how ‘when everyone’s super, no-one will be’? That applies to a lot of things. MENSA meet-ups, where everyone in the room is so clever that they all probably feel quite dim. The endless ‘improvement’ of washing up liquid, where – according to the ads – each new formulation makes the last one look like pointless, frothy dog mess, to the end that every product on the market is logically both amazing and terrible at the same time. And there’s also the tricky matter of the endings of blockbuster action films, which have now become so big and awe-inspiring that they’re on the cusp of becoming rather dull.

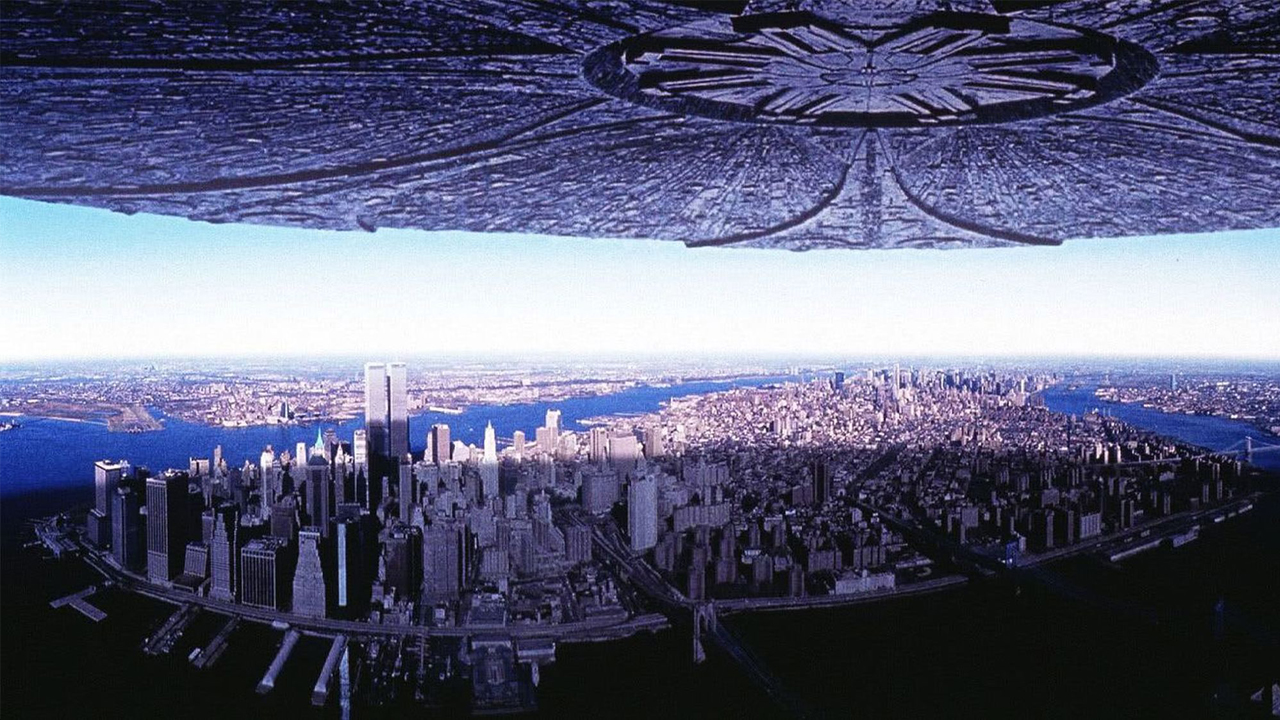

This isn’t the first time it’s happened. It all started back in 1996, when Independence Day realised that by shuffling impressive models of giant, murderous hubcaps across postcards of Important, Well-Known Places, it could instil in its audience a sense of apocalyptic dread so awesome that the accompanying horrors of schlocky writing and blunt emotional beats wouldn’t be a problem. We were happy to wave away the non-compatibility of Apple software and alien computer tech. We would not question the incombustible nature of New York’s dogs, or whether dropping 15-mile spaceships on top of the world’s major cities could actually, long-term, be considered a massive win for humanity.

The system worked. Despite its more granular film-making issues, Independence Day was an arresting slice of big dumb fun, and a huge hit to boot. Massive, high-stakes spectacle was clearly the way to go. In fact, movies were going to be so, damn spectacular for the next few years that it would be almost physically painful. A new bar had been set, and no-one dared not meet it, lest their film’s drama be deemed inconsequential and their visuals low-rent.

Independence men Roland Emmerich and Dean Devlin were the kings of the large scale disaster for a while. They replaced the aliens with a massive lizard, switched the incombustible dog for Matthew Broderick, and followed up with Godzilla. Then in The Day After Tomorrow, even as the genre was fading, Emmerich scaled up the antagonist considerably, trading in the giant lizard for the entire goddamn planet and casting a new ice age as the unremitting buggeration of humanity’s fortunes. Rapidly realising that a global disaster leaves little avenue for further expansion, he next innovated - in his movie 2012 - by basically just doing exactly the same thing again, but with global warming and solar flares, presumably because hot things are a bit scarier than cold things. Shut up, there was wiggle-room there. There was escalation. Sort of.

But it was clear that momentum was slowing down. That’s the thing about the shock of the new. It only really works once. And it’s not like Independence Day’s descendants sprang only from its own family tree. Everyone else had been at it too. Armageddon and Deep Impact both did planet-killing asteroids in 1998, awkwardly, just as Dante’s Peak and Volcano had butted heads (and magma) the year before. And The Core used the collapse of the Earth’s internal magnetic field as an excuse to dig a very deep hole and fill it with enough deliriously inaccurate techno-babble as to be voted the worst sci-fi film ever, by actual scientists.

And in the midst of it all, no-one seemed to notice that the danger was becoming meaningless through repetition, each collapsing city and bleeping nuclear countdown ultimately naught but background noise. Eventually, the bubble had to burst, and burst it did, as the ‘00s saw these singular, stand-out sprees of destruction largely give way to more involved, long-term, serialised genre epics, by way of Harry Potter, Lord of the Rings, the Star Wars prequels, and eventually the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

But now Independence Day is back, ready to raise the bar once more, with even bigger spaceships, bigger explosions, bigger devastation, and a scaled up sense of war-mongering horror from beyond the stars. Hell, it’s been 20 years. That’s plenty of time to let the literal and figurative dust settle, and make that stuff exciting again, right?

Sign up to the SFX Newsletter

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

Actually no. Because Marvel has now been around long enough to have kick-started the whole cycle again, and I can’t help feeling that Independence Day: Resurgence is turning up just after the wave has broken.

The MCU - as its ongoing character arcs have evolved, its shared universe has expanded, and its big team-ups have required bigger foes - has repeated the ‘90s pattern of escalation all on its own. The Avengers? Alien apocalypse. Guardians of the Galaxy? Galactic Apocalypse. Thor: The Dark World? Alien Elf apocalypse. Avengers: Age of Ultron? Robopocalypse. And of course, in parallel, the majority of Fox’s X-Men films have followed suit, with plots and climaxes driven by a variety of world-ending possibilities for mutants, humans, or both. And, of late, for Fox itself, the ever-impending loss of franchise rights back to Marvel arguably being responsible for the series’ recent rapid-fire escalation.

But the interesting thing is that, more than any other film or series operating on this kind of scale, the core Marvel movies have (mostly) earned it, building up to their catastrophic vistas through years of smaller, character-driven stories. Iron Man’s climactic, interdimensional clutch-save at the end of The Avengers isn’t affecting just because it’s impressive. It also matters because we’ve already seen Tony Stark’s steady growth from hedonistic jerk into Real Boy made of conscience and responsibility.

Ditto Age of Ultron, where, after dealing with alien-induced PTSD and growing up even more in Iron Man 3, one slip-up sees Tony’s hard work derailed horribly, at a huge cost. Captain America has had a parallel path, and so any peril he finds himself in – apocalyptic, political, or personal – is automatically filtered and amplified by our knowledge of his journey thus far. Impressive but hollow spectacle has been replaced with grand events where the stakes are not just The Thing That Is Happening, but also who it is happening to, and why.

But even so, it feels like we’re hitting a ceiling again. We’ve seen a major city half-destroyed. We’ve seen another city used as a weapon to (nearly) destroy the rest of the world. We’ve had Earth, its surrounding realms, and the wider galactic neighbourhood threatened multiple times. The next Thor film is named after the Norse end of the world, and the next X-Men movie is subtitled Apocalypse. Meanwhile, two of the most exciting and refreshing comic book movies of recent years have been Ant-Man and Deadpool, resolutely small, personal tales whose narrative consequences wouldn’t be known to anyone outside of those directly involved, whatever the outcome. They’re great because they’re the sort of films that made the Marvel Cinematic Universe resonate in the first place.

And there’s a sense elsewhere in the MCU that this realisation is spreading. Beyond the proliferation of new origin tales for new heroes that will come with the start of Marvel’s Phase Four, the just-released Captain America: Civil War is almost an implicit statement that things have gone too far. The film’s plot is built upon the idea of tearing down the surface spectacle of the biggest recent Marvel movies and facing the real, human cost (often literally) buried underneath. It’s a film about the hangover from a party that got out of control, and the need to reign in the destruction for the greater good. It’s certainly a parable that works both inside and outside of the movies’ fiction, and one that needs to be observed, should the incoming galactic showdown with Thanos in Avengers: Infinity War mean anything after so many years of build-up.

As for Independence Day: Resurgence, I just don’t know. Big dumb fun and nostalgia might be enough. The return of Jeff Goldblum might deliver the audience attachment required to make another spate of exploding cities matter. I hope so. I’m kind of looking forward to it. But nothing like as much as I was in 1996. I’ve seen a lot more since then, but I’ve also seen a lot less, and frankly I’ve been spoiled by both.